Cyberpunk 2077 has been subjected to a tsunami of criticism. Much of this is legitimate and fair—the bugs and technical issues, the antiquated open world design, and the underwhelming RPG mechanics are all clearly identifiable flaws. There is one accusation being made of the game, however, that I find completely baffling, and this is the notion that Cyberpunk has nothing to say.

This is a common complaint amongst critics and players alike. NPR's scathing review of Cyberpunk hinges almost entirely on the notion that Cyberpunk is thematically empty, while Eurogamer's (generally excellent) review states "So much energy has been directed at the question of Cyberpunk 2077's parable. Of what it says. It says nothing."

Personally, I find this a strange remark to make toward any game. All art has something to say about the world in which it was created, whether it intends to or not. But the idea that Cyberpunk has nothing to say is particularly odd, as it practically screams its message from every skyscraper-packed street corner.

I think these criticisms stem from a more general thematic weariness. The haven of corporate materialism that Cyberpunk presents us with has been explored exhaustively both in broader cyberpunk fiction and videogames themselves. Aesthetically, Night City is a pastiche of Gibson's Sprawl and Scott's Los Angeles, a vision of the future that is itself four decades old. Meanwhile, from Syndicate to Fallout to Bioshock to Grand Theft Auto, games have satirised and philosophised about capitalism for decades, with varying degrees of success, and varying degrees of hypocrisy.

Watching a multibillion-dollar company make a game about how capitalism sucks is always going to come with a side of cognitive dissonance. When you walk out into Night City and see the oppressive crush of buildings, the kooky-looking NPCs, and the neon billboards trying to sell you various flavours of depravity, it's easy to roll your eyes and write Cyberpunk off as another shallow virtual satire.

And it's true that Cyberpunk's city is shallow, but it isn't intended as a parody. At least, not primarily. Everything in Night City is surface. You can tell by looking at a person what gang they're affiliated with, what corpo they work for, what cyberware they're carrying. Memory too can be externalised in Night City, able to be recorded, edited, and played back in the form of "Braindances", used as cheap entertainment for the masses. Its most advanced technology, locked away in Arasaka Tower, can even suck the soul out of a person and stick it on disc.

In other words, Cyberpunk's world does not permit a person an internal life. Everywhere you look, Night City wants to reach inside you and pull whatever's in there out for everyone to see. In an environment where your memories can be edited and your personality digitised, who you are becomes a vital question.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

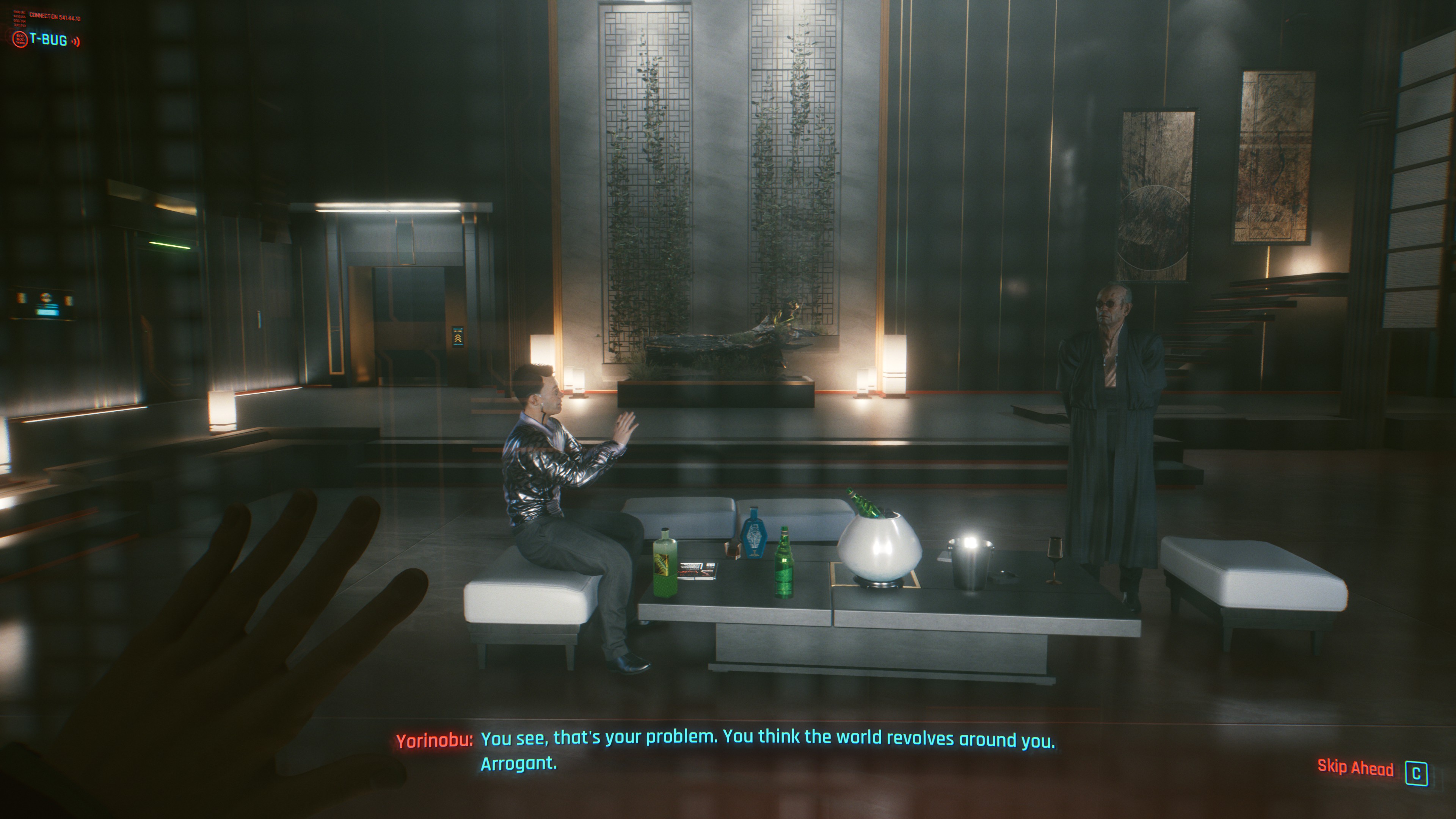

It's this question Cyberpunk's story seeks to answer. This is most evident in the game's protagonist, V. In the first half of the game, V's only goal is to make a name for themselves, to become more than just an Edgerunner doing small-time jobs for the city's various fixers. V's wish is granted by the chance to pull off an ambitious heist, stealing a slice of that soul-sucking tech from the Arasaka Corporation.

V successfully pulls off the heist, but at considerable cost. Their best friend Jackie is killed, and so is V. That is, until the Silverhand Construct V stole brings them back to life. But the construct's motives are selfish—it needs V alive so it can quite literally overwrite their memory with that of Keanu Reeves' rockstar terrorist.

Having your main character's personality erased by an algorithm designed by the biggest corporation in Night City is not exactly a subtle metaphor for our own battles to stand out amidst the howling void of our own technological present. But this is just the central pillar of the game's exploration of seeking an identity in the face of a city that actively wants to dehumanise its inhabitants. Almost everyone you meet in Night City is looking for a hook to hang their hat on. Panam searches for a new calling after being displaced from her Nomad family. Judy Alvarez has drifted through life looking for purpose ever since her childhood hometown was destroyed to make way for a reservoir. Even Takemura, Sabu Arasaka's loyal and steadfast bodyguard, finds himself at sea after the Emperor is murdered and the crime pinned on his most faithful servant.

It's no accident that V's motives are explicitly selfish throughout the game.

Cyberpunk's story is ultimately a search for the self, a goal which is hard to achieve when your entire way of thinking is coded in the language of gain and profit. It's no accident that V's motives are explicitly selfish throughout the game, first to find and then to save themselves. Whenever V works with someone, that relationship is nearly always transactional, either for hard cash or a mutual scratching of backs. Personal relationships that transcend material exchange are hard come by.

Some of the criticism aimed at Cyberpunk is based on the fact the game isn't more expressly anti-capitalist as cyberpunk fiction 'should be'. But cyberpunk is rarely so straightforward. While the genre does generally revolve around rebels and outsiders, in most cyberpunk fiction, the house usually wins. In fact, often the house barely registers the protagonist was inside in the first place. Cyberpunk isn't so much about resisting capitalism as identifying how difficult capitalism is to resist, because it simply absorbs whatever bullets you fire at it and sells them back to you at a premium.

Cyberpunk represents this perceived futility of the fight well. One of the best conversations in the entire game occurs while V and Takemura are scouting out an Arasaka warehouse from an adjacent building. As they await nightfall, Takemura notices a cat sitting on the railing—possibly the last cat yet to flee the city's pollution and noise. Takemura wonders if it's a Bakenoko—a spirit that can bring the dead back to life (a few moments later Johnny appears, lounging next to the cat).

This leads them to talk about their mutual upbringings, and how Takemura became the Emperor's bodyguard. He senses V is judging him for his work protecting the symbol of consolidated power in Night City. "Unlike you and Mr Welles, I did not take the easy path", he responds. "You oppose the corporations, their order, their world, in a mindless way, yet you offer no worthy alternative. You show me filthy streets as if no other world exists, as if nothing else is possible. What of the millions who work for Arasaka and receive stability, safety?"

Takemura represents the ideal capitalist worker. Diligent, loyal, hardworking, and receiving a fair exchange for his labour. Money, status, and self-worth. His argument is a familiar and compelling one. But none of Takemura's admirable qualities stopped him from being thrown down the ladder entirely by circumstance and the dog-eat-dog nature of Night City. The system may have enriched him, given him access to privileges most never experience. And yet, he is still a victim of it, something which is impossible for him to see. "We cannot fix everything at once," he vaguely concludes as the Bakenoko slinks away.

CD Projekt RED is now one of the most famous game development companies in the world, explicitly part of the culture it once purported to rail against.

Cyberpunk may not be a radical work, but it is well versed in the core themes of the genre, and the way it explores the dehumanizing and brainwashing effects of hard capitalism on individuals is both thought-provoking and emotional. For all that I enjoyed Cyberpunk's more deliberate musings, however, I think the game's most interesting quality is how its thematic anxieties reflect those of the developer that made it.

CD Projekt RED has long presented itself as an outsider studio, the quirky Polish developer with strong beliefs in consumer advocacy, who took an obscure monster hunter and transformed him into a worldwide phenomenon. That studio no longer exists. CD Projekt RED is now one of the most famous game development companies in the world, explicitly part of the culture it once purported to rail against. It's more than a coincidence that their latest game obsesses over identity crises in the face of rampant capitalism. Or, as Johnny Silverhand puts it: "Worst thing's when they switch up your identity and you never even know you've become someone else."

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.