Our Verdict

Brutal, beautiful, emotion-wringing turn-based storytelling muffled by flat base design.

PC Gamer's got your back

“'Tis a vile thing to die,” Shakespeare wrote, “when men are unprepared and look not for it.” This is precisely XCOM's favorite way to kill you. Enemy Unknown has just unexpectedly murdered my best soldier. Not with a jetpacking alien-cyborg. Not with a lucky grenade. Not with a plasma gun.

An exploding forklift has just eaten the life of my most decorated alien-killer.

I'm heartbroken. Embarrassed. Over his 22-mission career, Captain William Wonka became my brave combat medic. He rescued several French civilians. He defied low-percentage rifle shots to save his comrades. Now he's face-down in a truck stop, flatlined by a forklift that—as vehicles occasionally do in XCOM—became a slow-burning bomb two turns ago when an alien accidentally shot it.

I hold a tiny funeral in my mind. Bagpipes. Last rites whispered over a chocolate grave: "...Good day, sir."

He's permadead, but I have to carry on. This is XCOM's unique expectation: soldier on in the face of loss, grit your teeth when they've just been broken. Aliens are invading, and the multinational military organization you run is the underdog. Only good science, good strategy, and good luck will level the playing field.

In taking on the series, Civilization creator Firaxis has shown reverence and understanding for what makes it special. XCOM's ingredients are hard to recombine: strategy with consequences. A technology metagame where you use the enemy's weapons against them. Emotional attachment to player-created soldiers and a feeling of meaningful death when you lose them. High-fidelity destructibility.

Firaxis keeps these spiritual details intact, but it also has the guts to melt down and modernize some of the series' mechanical details. The old action-points system has been recast in a less arithmetical form: in combat, any soldier can move once and take an action, or they can make a single, longer move instead. Firaxis also has a clever approach to the fog of war. Every grid of movement steadily pulls back a curtain on things that want to kill you; unseen enemies, however, will occasionally indicate their general direction. This change eliminates the impatience that arises when you can't figure out what rock the final alien's hiding under. Combing the map is now less a frustrating hide-and-seek and more a murderous Marco Polo.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Not all of Firaxis's new ideas are this successful. They've oversimplified the aerospace metagame to get you to focus on the great ground combat, and your base is visualized with all the detail of a screensaver. But overall XCOM's turn-based campaign is more coherent and elegant than anything the genre has granted us in years. Managing and developing a relationship with a team of soldiers resurrects the childlike joy of commanding a squad of action figures, and sending them on dangerous missions to your kitchen.

Area 51

XCOM's secret underground base is where your action squad lives. Between ground missions, time in this bunker is spent allocating resources to research, air assets, and toys for your soldiers (who, I like to imagine, are putting their ear to your office door, listening with crossed fingers, hoping to catch word that you're investing in barracks upgrades that boost their survivability or experience gain rate).

There are plenty of plates to spin. On Classic and Impossible difficulties especially, almost every investment is a chin-stroker: your commitment to a long-term strategy is regularly called into question as opportunities to unlock something that'll help you immediately present themselves. To fully outfit my team with Carapace Armor, I sold my only UFO Flight Computer on the gray market. My soldiers had more HP, but I'd sacrificed the opportunity to let my scientists tinker with the device and discover new technology. Until I could pull one out of another downed UFO, at least.

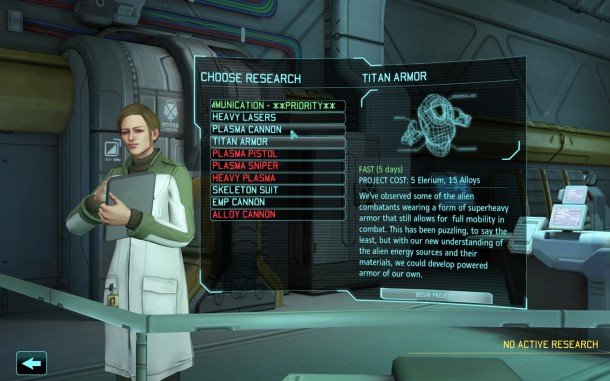

Managing your scientists and engineers is the nucleus of the metagame. They'll notify you of new projects, and you'll say “Laser shotguns sound scary, please go invent them.” Research and production is mostly a linear progression (plasma guns are a flat-out upgrade over lasers, which beat your initial ballistic weapons), but stellar mission performance or having an eye for efficient resource spending can create shortcuts to endgame tech.

But as you spend more time in these areas, it sinks in that your base does a pretty poor job of evolving with you. Your base resembles an ant farm—a clever template that had the opportunity to provide a constant sense of activity while granting an all-at-once glance at your paramilitary bunker. New rooms appear as you erect more workshops or satellite uplink facilities, but you can never really put your nose up against the glass. As you revisit your base's layers, you start to notice that nothing changes; if I'm producing a medkit or a cannon, if I have five scientists or fifty, the facilities look identical. “The new engineers arrived this morning, Commander,” my technician reports. Well, where the hell are they ?

It's baffling that bases didn't get more love. Given the cross-section design, it's a missed opportunity that none of the ants in your farm express themselves—it's like buying a plastic hamster mansion but owning fabulously boring pets. Having a few tokens of your discoveries (and conquests) pop up around the base would've made a huge difference.

The decision to represent soldier injury almost identically to how it was done in 1994 is especially disappointing. When soldiers are wounded, they go on medical leave. Mechanically, I love this: it encourages you to cultivate your bench, and it gives tactical mistakes more gradients. But when a soldier returns home hurt or dead, your base conveys this in the least interesting way: a few words of automatically generated text.

Losing a character you've invested 10 or 20 hours in is one of XCOM's most significant events, but it may be more tragic that XCOM is so unenthusiastic about reflecting or preserving this history. I would've loved to see injuries actually visualized: why not create a sickbay where I can check up on Sergeant Mal Reynolds, who I dumbly put in the crosshairs of a Sectoid Commander in Mexico? My Christmas wish would've been for a system where the moment of death is somehow recorded, letting you relive and reevaluate your mistake or martyr's sacrifice.

Boots on the ground

Still, in the arena that counts the most—ground combat—Firaxis gets it thigh-slappingly right. It's here they remind us how good they are at making boardgame-like videogames: they know how to take something static and turn-based and turn it into a sci-fi chess diorama.

Beautiful boards are the foundation for this. Every map in XCOM feels handcrafted and familiar; your skin crawls a bit when a Muton busts open the door of a record store (“Step away from the ABBA, bastard!”) or a Chryssalid crawls across a train track. Tiny, intricate, manmade things populate the game. Fast food counters, beer taps, and bus seats have offered me cover. I've shielded a soldier I named Vin Diesel behind a gas pump.

And it all breaks like it's made of crackers. Almost every weapon is a wrecking ball. A Plasma Rifle's splurt of radioactive jade cuts a 15-foot hole in anything it touches. Rockets and grenades chomp half-ton bites from brick walls. The fragility of these spaces expresses the aliens' power, personality, and the urgency of the war you're waging. And then there are the UFOs, which flip the script—they're foreign, cavernous, and bottlenecky in a way that impedes flanking tactics.

40 hours in, I'm still occasionally encountering new maps. The only shortcoming of the levels is that they don't express Earth's diversity. If you're saving civilians in Egypt or China, you'll probably do it in a vaguely Western convenience store. A desert, Arctic, farm, or jungle tileset would've been welcome.

Most of the missions you're sent to these places to complete are standard, satisfying kill-'em-alls. The others introduce twists that—hilariously—endanger your soldiers even more: VIP escort, bomb defusal, civilian rescue. The latter are called Terror missions, and they unapologetically stack the deck: a dozen AI civilians are spread across the map, and how many you save reduces the panic level of the hosting nation. Innocents die in one shot, and aliens don't consider it unsporting to kill ones that you haven't even seen yet. Oh, and there are probably some Chryssalids running around. You know, that alien that converts anything it kills into a durable super-zombie. Good luck!

Terror missions are XCOM's magnum opus of helplessness. Few games can prompt the player to make heavy decisions without making a big, narrative show of it, but XCOM does here. Do I put my star soldier in guaranteed danger to rescue a doomed lady? Halfway through my campaign, two Chryssalids were inches away from pouncing on a civilian inside a British pub. My Heavy had a clear shot. I put a rocket between them, bursting human and caustic alien blood in all directions. It was the only choice. She was a goner, right? Killing her saved lives, right? No one appeared to reassure me I made the right call.

The emotional thud of death—friendly, collateral, and enemy—is partly owed to Firaxis' animators. In defiance of the game's unnecessarily short-leashed camera zoom, its characters articulate like stage actors playing to the back row. Aliens and humans turn to face new threats the moment they're flanked. An explosive kill activates generous, gravity-defying ragdolling, long enough to drop a xenophobic slur before the corpse hits the ground. Mutons—XCOM's green-armored linebackers—chest-thump when they score a kill. Cyberdiscs fold open like Swiss Army frisbees to reveal their arsenal. Sectoids scamper like evil toddlers, with a gait that conveys the weight of their Roswellian brains.

The alien AI inside those heads is generally great, too. The alien playbook is consistent: get spotted, run the hell away into cover, then exploit your weapons' greater range and power. If those tactics weren't so effective, I'd call it predictable; a sprinkle more behavioral variance, or even mistake-making, would have been welcome. But they're plenty brutal. Psychic enemies are incredible jerks, stealing the free will of your squadmates and making them shoot one another or commit suicide. When this happens, you have a turn to snuff the psychic. I tend to pull everyone out of cover, spending every active ability and explosive ordinance available to dump damage into the mind-controller. Moments like this are when all of XCOM's strengths are laid out: a life, an asset you've developed, is on the line, and there's a measurably small chance that they'll live. Every shot fired trying to save this soldier is a held breath.

Beyond the restricted zoom, a couple of other camera-related issues did annoy me. The isometric camera tends to fight you when you're trying to aim grenades and rockets at their maximum range. And the cinematic camera occasionally points itself at walls or leaps away during a death animation you want to see. Worst are the moments when XCOM can't seem to intuit what elevation level of the environment you're trying to examine, and renders the wrong slice.

When you end the campaign, which took me 23 hours on Normal, multiplayer awaits as a battleground to test your XCOM skills against friends or random people on the internet. With only five maps, the mode is probably too content-light to become a mainstay, but I'm glad it's in here, and that it gives a chance to have a go as the aliens, or even field a strange interspecies team of up to six units. Any alien or customizable human you choose to send in has a point price attached to them, with a per-team point ceiling specified during pre-match. A bug frustrated in a few of my matches, preventing me from moving troops.

Uncommon

XCOM is a style of game that arguably hasn't existed since original creator Julian Gollop released Laser Squad Nemesis in 2002; much of its appeal comes from the fact that it's filling a long-standing void. That makes it easier to shrug off its flawed presentation of your base and other key elements. That includes inexplicably limited soldier customization, which has fewer haircuts than the actual military and offers a diverse selection of 15 nearly-indistinguishable American voices in a game where you command soldiers from 16 different countries.

Mostly, it's a game that understands that loss can be leveraged in parallel with rewards to tell a great story. It paints from a unique emotional palette: doom, sacrifice, luck, surprise, revenge. It uses death like most of us use mayonnaise, and Impossible difficulty practically makes XCOM into a Mourning Simulator.

But this is where imagination fills in the gaps of XCOM: Enemy Unknown's purposefully lightweight script. The tale we tell ourselves of Captain William Wonka and his untimely death by an exploding forklift is much more personal and permanent than a pre-cooked narrative about alien invasion. Hemingway would've appreciated this approach. “All stories, if continued far enough,” he said, “end in death, and he is no true story-teller who would keep that from you.”

Brutal, beautiful, emotion-wringing turn-based storytelling muffled by flat base design.

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer way back in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are Hunt: Showdown, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Counter-Strike. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging.