Why people love Nier so damn much

Unpacking the hype around Nier Replicant, Yoko Taro, and his controversial and strange games.

We gave Nier Replicant a 90 in our own review, and so did several other reviewers. Which is surprising considering the original Nier was a flawed RPG that seemed likely to die in obscurity back in 2010. Instead, it became a cult classic that now has a fantastic sequel, spin-off books, and a devoted following.

If you're not one of those fans, the fervor for this bizarre series and its creator Yoko Taro might seem impenetrable. After learning all about Nier and its history myself, I'm here to explain why people love it so damn much.

So, what is Nier?

Do you like games that make you question the meaning of your own existence? Then you'll probably love Nier.

If you want to understand Nier, you're going to have to embrace the fact that you're going to be at least a little confused by everything. It's part of the charm. Nier Replicant ver. 1.22474487139… is an action RPG remake (or "version upgrade," as its creator Yoko Taro insists on calling it) of the original Nier that launched back in 2010 for the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3. It's a little complicated, but that original Nier was actually split into two separate games that have different protagonists—though the story, gameplay, and everything else is pretty much the same. Think Pokémon, basically.

Here's a breakdown of the two versions:

- Nier Gestalt was released globally, but in North America and Europe it was simply called Nier. It featured an older protagonist who was the father of a central character named Yonah. Nier Gestalt released on the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3.

- Nier Replicant was released only in Japan. It featured a younger protagonist who was the brother of Yonah. This is the version that modern remake, ver. 1.22474487139… is based off of.

What you need to understand, though, is that both of these versions weren't very good. Nier had a mostly bland and empty open world, rote sidequests and combat that never escaped feeling a bit clunky. It was clear Nier was made on a lower budget than the popular action games it was up against at the time. But it was also fascinating. The story and characters were compelling, bizarre, and deeply tragic. This became one of Nier's best and enduring qualities. Its story sets itself up like a classic adventure similar to early Legend of Zelda games and then detours into shockingly dark, twisted, and macabre territory. Do you like games that make you question the meaning of your own existence? Then you'll probably love Nier.

Though it plays like a fairly standard action-RPG, Nier is also remarkable for its habit of switching genres on the fly. One minute you're beating robots to death with a sword in an underground lab and the next you're playing a top-down shoot 'em up dodging dozens of slow moving bullets. At one point the game switches perspective to mimic clicky-clicky RPGs like Diablo, while another section is a full-blown text adventure. It's wacky and different, and people like different. So even though Nier was a lukewarm success at best (it only sold an estimated 500,000 copies), a few people saw the glimmers of potential. For fans of Nier's creator, this is exactly what they're used to.

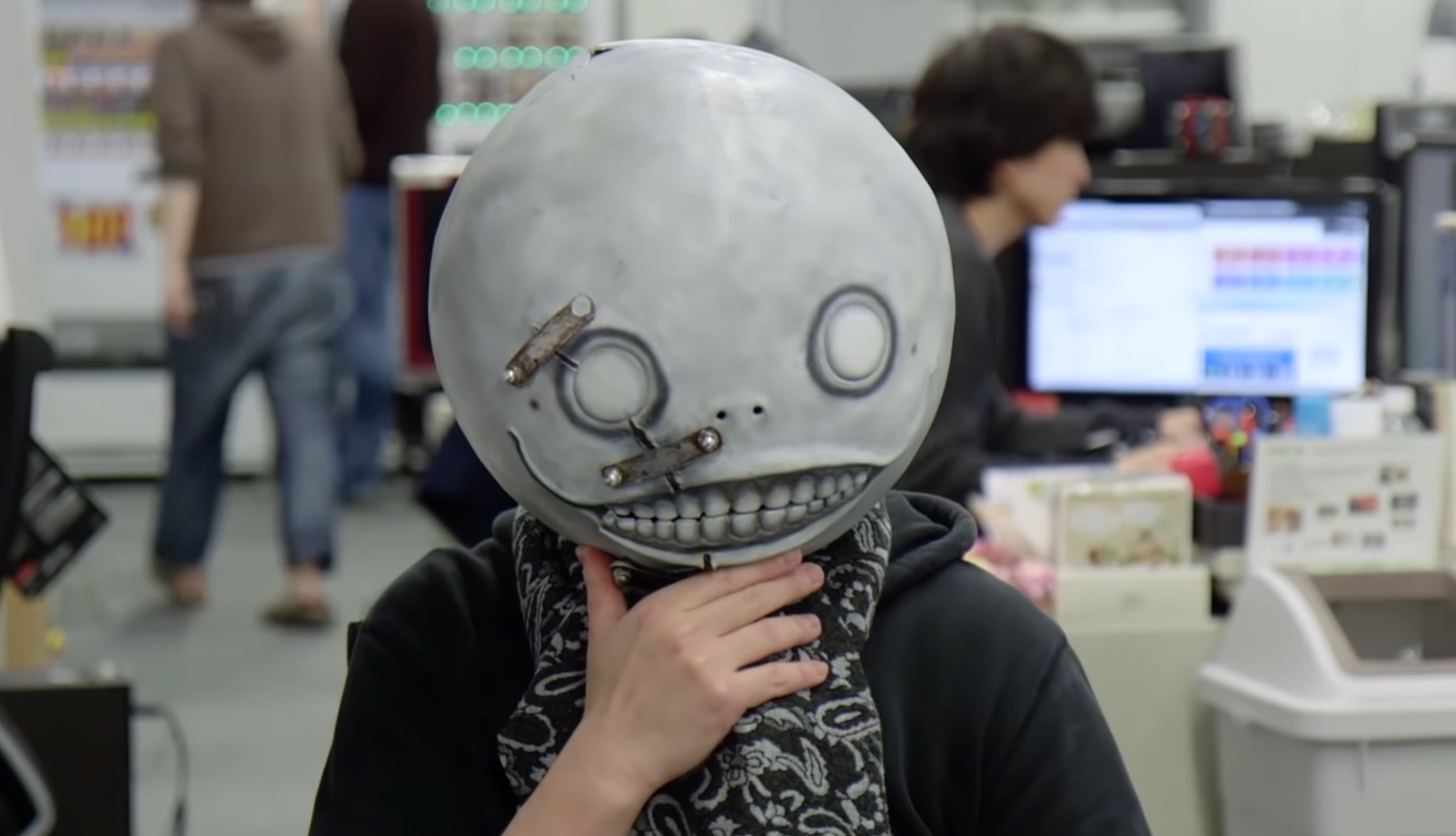

The man in the strange mask

A big part of what makes Nier so endearing to people is the man who helped create it, Yoko Taro. He's a controversial Japanese game developer who is most well-known for hiding his face inside a giant, creepy mask. Why? Well, apparently Taro hates giving interviews or doing public appearances and so at some point he started wearing the mask to hide his true identity.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

To say that Taro is an eccentric is probably putting it too lightly. In an age where most public-facing game developers go through proper media training and are always on message, Taro is unpredictable and wild. Hell, just yesterday he released a statement chastising Nier Replicant's publisher, Square Enix, for being too enthusiastic about the game and suggesting it probably will be another commercial failure—just like all his other games. So, yeah, he's a strange fellow. But it's that strangeness that draws people to Yoko Taro. And his eccentricity isn't just a publicity stunt but something that is deeply woven into the games he makes.

This all started with Drakengard, Yoko Taro's first game that was released on the PlayStation 2 in 2003. If Nier is merely strange, Drakengard is fully batshit. It's hard to explain it without going into intense detail about the lore, but what sets Drakengard apart from other RPGs is just how bone-chillingly dark and twisted it is.

Do you want some examples? Okay, you asked for it:

- One of the main characters is named Leonard and he joins the party shortly after his three kid brothers were butchered by soldiers while Leonard was off in the forest masturbating to the thought of little kids. Yup, he's a pedophile and is very torn up about it. He tries to kill himself but a fairy shows up and manipulates him into forming a magical pact with her in exchange for his eyeballs.

- Another main character is an elven mother driven insane by the death of her child. She slaughters and eats children because she thinks she'll be able to "protect" them inside of her womb. In one of Drakengard's many different endings, she is eaten by a horde of giant celestial babies. Now that's poetic justice!

- In one alternate ending, the main character's sister commits suicide because it's revealed that she harbors incestuous feelings for him. It's not clear if he reciprocates, but I doubt it because he's clearly in love with his pet dragon that also stole his ability to speak.

- In Drakengard 3, the main character was sold into prostitution as a child but is also a divine songstress on a mission to slaughter her five sisters and bring about the end of the world. She also has a flower growing out of her eyeball and rides a dragon with the voice of a child. Each time she kills one of her sisters, she forces their disciples to become her sex slaves. There's a cutscene where she explicitly tells one to prepare for sex by washing "front and rear," so you know she means business.

That's just an infinitesimal slice of how fucked up, dark, and controversial Drakengard games can be. But what's key about Taro is that, even if his intentions seem impossible to divine, there always some kind of logic to it.

Drakengard itself is a kind of warped commentary on videogame violence. When writing its main cast, Taro reportedly couldn't understand how typical videogame heroes could be so violent murderous in pursuit of their goals, often slaughtering enemies wantonly without much thought. The only explanation he could think of was that they must be insane, so he leaned into the idea.

Like Nier, though Drakengard developed a devout following because the series was so fascinating despite also being so flawed. The gameplay is an awful mix of bad Dynasty Warriors-esque combat and Ace Combat But With Dragons. The story oscillates between incomprehensible and cringey and requires a ton of additional reading to understand what's even happening, and in order to experience all of their different endings you have to do a lot of pointless grinding.

At best Drakengard is strangely engrossing and at worst it's like someone reciting the ending to Neon Genesis Evangelion after watching it while high on cold medicine. It is strange and frequently frustrating, but at least it isn't boring or derivative—unlike so many big-budget games. Similar to Nier, there were glimmers of potential through all the shit. And over time those glimmers resolved into a blueprint for game development that Taro would revisit again and again.

- The story is cryptic and layered and demands players' attention.

- Gameplay experiments with genre in unusual ways.

- Characters often have harrowingly tragic and unconventional backstories.

- Each game has multiple endings that answer only a few questions, pose new ones, or crack silly jokes. Each deepens your understanding of the game in some way.

- You never know what to expect and any cliches exist to be subverted.

These five pillars can be found in Yoko Taro's most well known games: Drakengard, Drakengard 3, Nier, and Nier Automata. (Taro didn't lead development on Drakengard 2 because he was mad at all the concessions he had to make during the first game—nothing is ever simple with Taro.) Playing through each in the order they were released would be like reading an author's rough draft of a script after each rewrite. With each new game, Taro got a little closer to making something truly special.

Nier Automata changed everything

Taro's eccentric personality has made him a bit of an auteur—similar to other renowned developers like Hideo Kojima. But it's important to remember these games are never made by just one person—and in Nier's case, another prominent member of the development team was producer Yōsuke Saitō (who often appears with Taro in interviews).

After Nier released, Saitō and Taro were eager to get cracking on a sequel. But Square Enix didn't like that idea because Nier sold so poorly and its developer, Cavia, imploded soon after Nier's release. In the four years since it launched, though, Nier's cult classic status grew rapidly. More and more people saw it as a diamond in the rough and wanted more.

In 2014, Square Enix changed its tune and decided to greenlight a Nier sequel. But the combat had to be better, so it tapped in PlatinumGames to help. As it turns out, PlatinumGames was also made up of big Nier fans, and it insisted that if it were to make a sequel that Taro had to be the director while Saitō became its producer.

Thanks to PlatinumGames' experience making killer action games, Nier Automata became a huge success. It was also the best iteration of Taro's blueprint.

Set thousands of years after the events of Nier, Automata was a story about humanoid androids fighting to rid the earth of an army of machines built by alien invaders. Like Nier, it was fundamentally an action-RPG that frequently transformed into other genres entirely. Several major sequences play out like bullet-hell shooters, where players pilot a flying exosuit from a fixed perspective while fighting waves of aerial enemies that fill the screen with an absurd number of bullets. Later, the game introduces a hacking minigame that plays like a twin-stick arcade shooter, and there are even a few sections that dip back into text adventure territory. Basically, it took all of Nier's most interesting ideas and polished them. And with Platinum Games, notable for excellent character action games like Bayonetta, developing it, Automata's third-person combat was challenging and graceful.

What really made Automata soar, though, was Taro's refined approach to storytelling. It's still dark, tragic, and bizarre, but the mix of those ingredients is much more measured. Instead of punching you in the face with dreadful fatalism right away, Automata offers you some cookies and pleasant conversation first. But when it does hit, my god. It hurts. At its core are familiar RPG themes like love and fate, but Automata is uncommonly nuanced in how it pokes and prods at everything from the meaning of life to what happens when we die. It's a heavy and violent game, but it's also heart-rendingly gentle and contemplative.

People love Nier because there is nothing else like Nier. It's a kaleidoscope of always-shifting ideas set in a world that is tortured, satirical, wistful, and tender.

Nier Automata also pushed Yoko Taro into the mainstream (something I'm sure he resents). As of this year, it's sold over 5.5 million copies—a huge success for considering its predecessor sold 500,000—and is widely celebrated as one of the best games of the past decade.

That brings us back to Nier Replicant. A lot of players believe Replicant has the better story and characters, even if Automata was overall the better game. Replicant is a do-over for 2010's biggest cult classic and, if you're a fan of Nier Automata, a chance to dig even deeper into its world and lore.

People love Nier because there is nothing else like Nier. It's a kaleidoscope of always-shifting ideas set in a world that is tortured, satirical, wistful, and tender. And even if Yoko Taro's games are often deeply flawed and sometimes profoundly unfun, at least they're always fascinating.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.