Why PC games should never become universal 'apps'

A more holistic view

Up to this point, this article is an objective description of exactly what you can—and more importantly cannot—expect today if you buy a game as a UWA on the Windows store. However, that alone is not what fuels the ongoing discussion about this topic: there are also concerns about what the widespread adoption of the Windows Store and UWP would mean for the future of PC gaming, both as a medium and as a marketplace. This debate is inherently more subjective and based on speculation, but I believe it is an important one to have.

It actually started a few years back when Gabe Newell called Windows 8 a “catastrophe” for the PC space—as it turned out, he was generally right, and Windows 10 was in a large part designed to recover from that catastrophe. This time we have Tim Sweeney leading the charge and being suspicious of another attempt to change the way Windows programs are distributed.

Some younger readers, or people who haven’t been following the PC market for long, might find it difficult to understand why such well-established industry figures who have often worked successfully with Microsoft (or even worked at Microsoft) in the past would take such a strong stance. But with some historical context, it’s not so surprising after all.

History and Context

Microsoft as a company has been the subject of many investigations for anticompetitive behavior in the past, both in the US and the EU. One particular strategy uncovered and named during these investigations is Embrace, Extend, and Extinguish: it involves entering a market with an open and standards-compliant platform, subsequently adding proprietary features and using those to disadvantage the competition.

How does this relate to the current discussion about UWP and games? Microsoft, ever since the release of the original Xbox, only seem to truly remember PC gaming in one of two scenarios:

- When they need it to prop up an ailing project or product; or

- When they see a new way to monetize it.

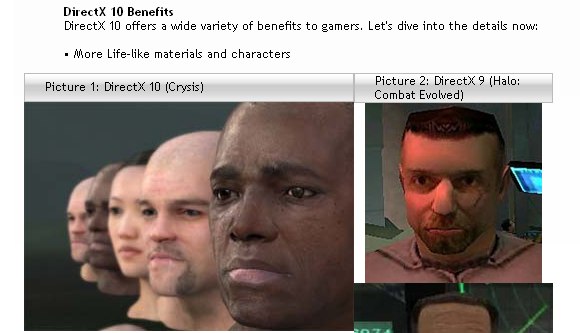

Some examples of this pattern include the DirectX 10 exclusivity push with Windows Vista, the abortive attempt to introduce paid GFWL subscriptions and subsequent gradual abandonment of that platform, and most recently the restriction of DirectX 12 to Windows 10.

At this point in time, their efforts at establishing a presence in the phone and tablet spaces are clearly not bearing fruit (Surface revenue is on the rise, but phone sales have fallen off a cliff), and their console is struggling to hold its own against its primary competition. As a company-wide countermeasure, they are designing a uniform platform, clearly taking cues from the mobile app store model—and what company wouldn’t be impressed by Apple’s revenue streams?

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

However, a unified programming and distribution platform is no help at all to your corporate strategy when no one is using it, which brings us all the way back to gaming: why not use some of your investment in console games to try and increase the popularity of your new platform?

Potential consequences and the future

The reason I went into some detail about Microsoft’s history, circumstances and outlook is to make it clear that their primary strategic objective is to make sure that UWP and the Windows store is a success, not that gaming on PC is as good for enthusiasts as it can be. Once we recognize this, many of the design decisions which result in the limitations outlined in the first part of this article make sense.

What also makes sense is the concern of very smart and experienced people involved with the PC gaming market such as Gabe Newell and Tim Sweeney. Because the ultimate corporate goal of the Windows Store and UWP is clearly an Apple App Store-like situation where every piece of software sold for Windows is a Universal Windows App which generates some profit for Microsoft. Of course, Newell and Sweeney could well be primarily concerned about the impact of such a scenario on their own profits, but I believe that any gaming enthusiast should also be concerned to some extent, for reasons I will now try to explain.

If this future—one in which Microsoft gradually incentivizes UWP and the Windows Store at the OS level, and gradually disincentivizes Win32 and competing stores—ever came to pass, many of the wonderful things we love about PC gaming would be imperiled. The preservation advantages of perpetual backward compatibility. The large set of third-party tools free to interact with any game and enhancing or customizing our experiences. The competitive distribution market which results in the lowest prices and most frequent deals compared to other core gaming platforms.

And most near and dear to me, the end to a platform on which enthusiastic fans of a game can continuously improve and polish it, and ensure that it is easily accessible to future generations, even decades after the original publisher lost interest or ceased existing.

Handing Microsoft—or any other company, but given Microsoft’s history it’s particularly egregious—the metaphorical keys to the castle and giving them the possibility to enact such change, regardless of the likelihood of them actually implementing it, is something I can never countenance.

Conclusion

There was a lot of ground to cover in this article, and there is yet more I’d like to say. However, I feel like what is really necessary is a summary that makes it very easy to understand what I consider to be missing in the UWP ecosystem. I’ve boiled it all down to two questions, one from the user and one from the developer perspective:

- Can I, as the administrator of my PC, grant any application—regardless of its source—the ability to do anything it damn well pleases on the entire system—including to other applications and UWAs—without either myself or the developer of the application having to interact with Microsoft at all or overcome unnecessary hurdles?

- Can I, as an application developer, freely distribute my UWA to users by any means I deem adequate, without going through Microsoft and without any disadvantages in terms of features or user experience compared to selling them on their store?

The answer to both of these question is currently a resounding “No.” Only if this changes to “Yes” for both of them—and in a well-documented, implemented, technically solid way, not just vague promises—can I even start to consider UWP as a future platform for PC gaming on equal footing with Win32.

Microsoft’s replies so far have been inconsistent. For some obvious implementation issues, like lack of V-sync settings, a quick solution has been promised, and I see no reason to doubt that claim. When asked about modding, the conversation is immediately steered towards the publisher-approved and supported kind, with no word so far about the more common (and, arguably, important) case. On interoperability, there are only the most vague of promises.

Whether we will see solid technical solutions at Microsoft's upcoming Build conference or more promises remains to be seen.

At a recent Microsoft event, Xbox head Phil Spencer told PC Gamer “for most people that just want to go play a great game the UWA version doesn’t keep them from playing a great game.” Regarding developer concerns, all the answers point towards Microsoft’s upcoming Build conference at the end of March. Whether we will see solid technical solutions there or more promises remains to be seen.

So, am I telling you to not ever buy a game on the Windows Store? Not necessarily. It seems like Microsoft is going to publish all their first party games exclusively as UWAs, and if you really want to play one of those then your only choices are between Xbox One and UWA. In such a case, all the limitations and concerns outlined above don’t really weigh on the decision, and if you have a fast PC it will probably provide a better experience than the console.

However, one fact should be clear. If you buy a game as a UWA then, in many aspects such as user control, interoperability, moddability and the overall ecosystem, what you are getting is closer to a console game running on a PC than what we traditionally consider a PC game.