Why I love virtual desktops

It’s more than just snooping, I promise.

When it comes to videogames, I’m a terribly nosey person. I will go out of my way to rummage through an NPC’s belongings, hang around to eavesdrop on conversations and inspect every corner of the environment. So when a game lets me delve into the desktop of a personal computer, I am more than ready for a snoop.

Fabricated desktops have become a popular space for videogame storytelling, with developers transforming the virtual interface from a simple computer layout into a theatrical stage. Looking through text conversations is the new dialogue, photo files provide world-building, and the humble recycle bin is a treasure trove of hidden secrets.

I totally understand how creepy I sound. Looking through a stranger’s personal computer in real life is deeply invasive, but desktops can be used in a number of different ways in games without making you feel like you’re sticking your nose where it doesn’t belong. A desktop can impact heavily on the atmosphere of a game, provide insight into a character’s headspace, and transport you to another time. It can be like opening the doors to a haunted house or being invited in for a cup of tea.

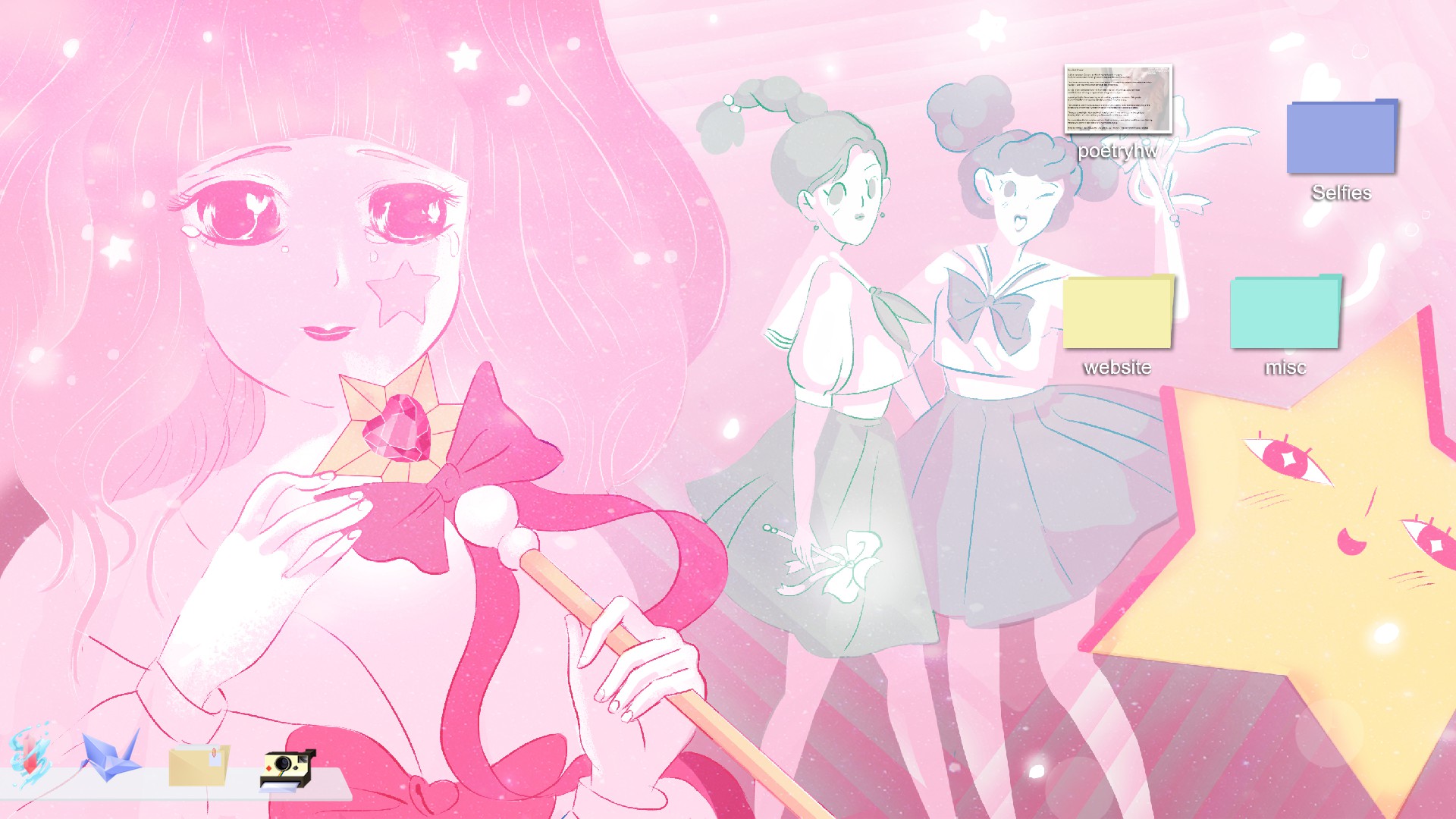

Cibele takes the tea route, welcoming you in. You play as a 19-year-old girl named Nina who is chatting with a young man through her online game. The cutesy pastel design and ambient music evoke the dreamy headspace of a young woman in love. You can dig through her diary entries, emails and photos to discover who Nina is, creating a closeness to the character. Looking around her desktop is like peeking into her headspace and seeing her thoughts.

Emily is Away’s chat software is another fun example. The game’s bulky MSN-era interface perfectly captures the awkwardness of high-school romance. As you chat with Emily, if you choose dialogue answers that are a bit too forward, your character will start typing it out, pause to think, then hastily backspace being too shy to say it. As I began chatting with Emily through the game’s desktop interface I started to feel like the awkward teen I once was, sending my crush a link to the sneezing panda video and praying they found it as funny as I did.

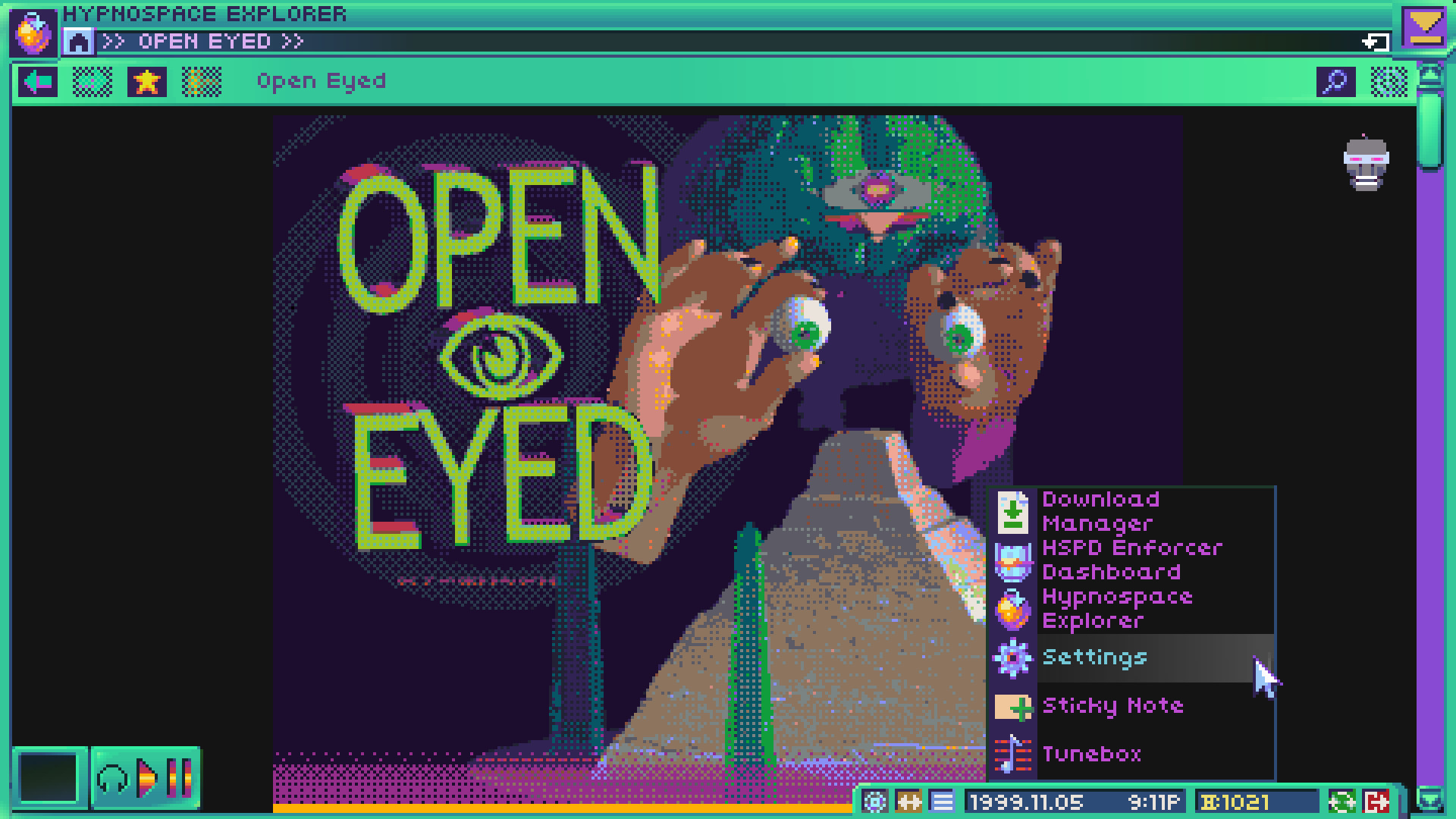

Hypnospace Outlaw tumbles back further into the past, its brightly coloured vaporwave design capturing the freedom of the internet back in the ’90s. Surfing the internet takes you to a wild west of websites where having a fiery background overlaid with lime green text is a deep form of artistic expression. You can also download a bunch of random crap from its fake internet, like virtual pets, helper bots that are the complete opposite of helpful, or dodgy anti-virus software that definitely isn’t malware.

Access granted

The desktop screen is a surprisingly effective place for solving a thrilling mystery. The two standout games are Sam Barlow’s detective dramas Her Story and Telling Lies, which, through their use of FMV, have created a completely new way to elevate game storytelling. Delving into the video databases and piecing together events is wholly satisfying, but Barlow also brings a physicality to his desktops.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

As you type words into the search bar in Her Story you can hear the sounds of old clacky computer keys, made all the more atmospheric by the fuzzy reflection of a flickering light in the computer’s screen. As I’m browsing through the highly classified NSA video files in Telling Lies a reflection of the computer user’s worried expression comes into focus. Sometimes her eyes dart to look at the time and occasionally she glances around herself, heightening the paranoia.

Interfaces aren’t just for computers. Games have also used mock-ups of mobile phone screens as ways of telling their narratives – especially in the horror genre. Games like Simulacra and Replica capture the thrill of riffling through someone’s personal info, trying to piece together the story behind its owner. Glitchy screens, text messages from characters presumed dead, and ghostly faces in the image folder make for a creepy experience.

Virtual desktops in games are more than just an opportunity to indulge my innate nosiness. These games use the structure of a fake computer or phone as a way to tell layered stories, and show that great interface design can set the perfect stage for a narrative to unfold.

Rachel had been bouncing around different gaming websites as a freelancer and staff writer for three years before settling at PC Gamer back in 2019. She mainly writes reviews, previews, and features, but on rare occasions will switch it up with news and guides. When she's not taking hundreds of screenshots of the latest indie darling, you can find her nurturing her parsnip empire in Stardew Valley and planning an axolotl uprising in Minecraft. She loves 'stop and smell the roses' games—her proudest gaming moment being the one time she kept her virtual potted plants alive for over a year.