Our Verdict

There are beautiful and tragic scenes, songs, and passages to find in WTWTLW's journey, but they're spread far too thin.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A story adventure game about turn-of-the-century workers and vagabonds.

Expect to pay: $20/£15

Developer: Dim Bulb Games , Serenity Forge

Publisher: Good Shepherd Entertainment

Reviewed on: Windows 10, Core i7-6700K, 16GB RAM, GeForce GTX 980

Multiplayer? No

Link: Official site

Narrative games are often in danger of being hard-to-read novels, books one 'plays' the reading of to the detriment of both the reading and the book. Where The Water Tastes Like Wine is a prime example of this danger. It tells over 200 tiny tales, and several bigger ones, at an agonizingly slow pace. There's truth to find within its choppy transcontinental trek, but it comes at the expense of sore eyes.

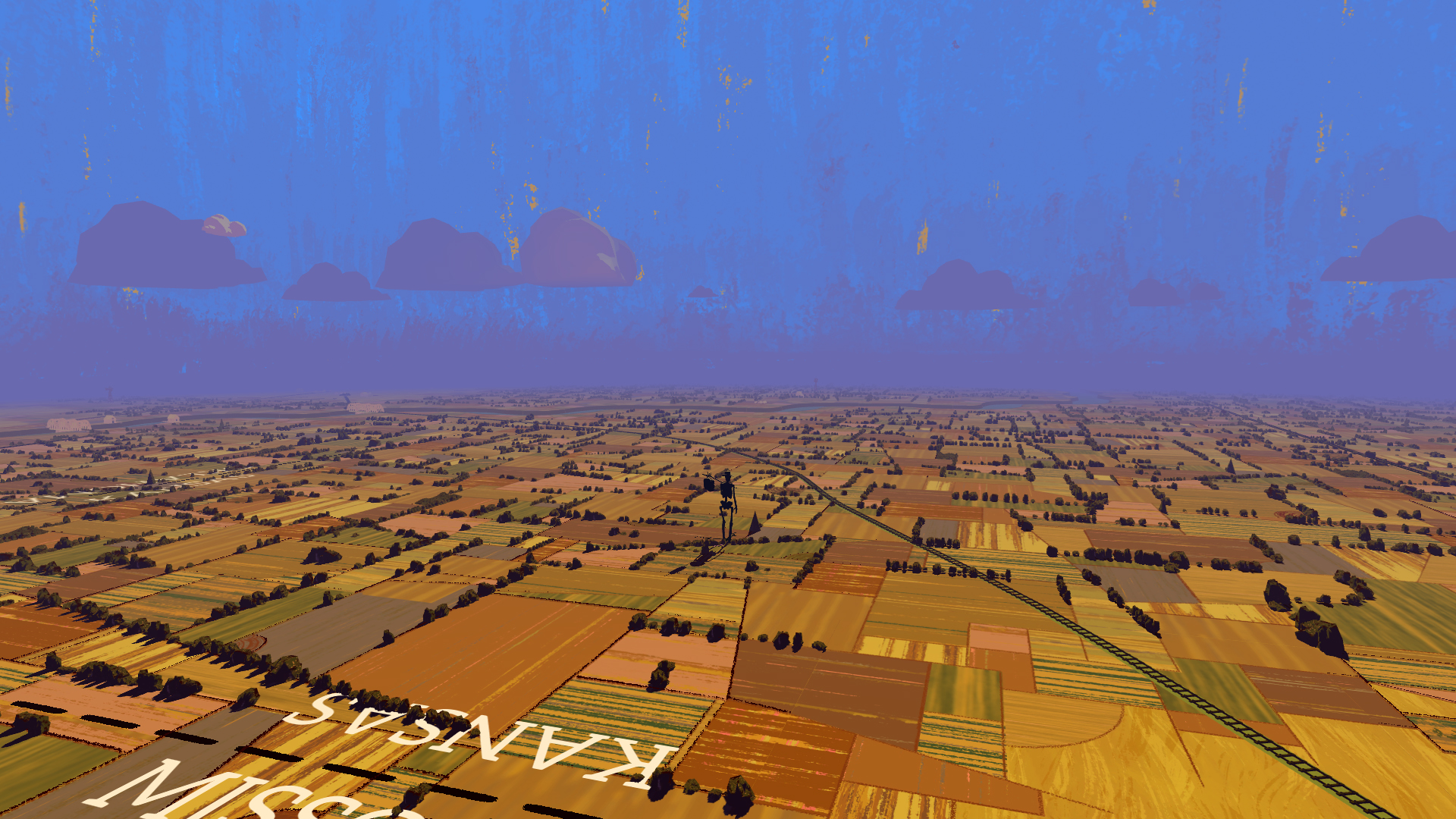

The 19th and 20th century microstories that make up much of WTWTLW—I'll get to the bigger stories later—are encountered by plodding across a garish map of the entire continental United States by foot, and sometimes by train or car, if you can hitch a ride. There's light personal upkeep to be done, managing rest, money, and health, but dying just resets you somewhere in America. Mostly, it's walking and whistling (which causes you to walk oh so slightly faster) while seeking out ugly, aliased story icons in cities and towns and remote farms.

Activating one of these icons cues an illustrated vignette with narrated text, sometimes with a few simple decisions to make. Many of these encounters are not so much 'stories' as situations, prompts, or descriptions of realist photographs: A thunderstorm. A dead kid. A friendly couple in a lighthouse. A man burying his dog.

There are fragments of hauntings, too. Some fail to be truly weird, such as the spooky ghost twins, or the radio that turns off every day at the time its owner died. But others are memorable, snappy supernatural scenes, like the new grandfather so excited that he hurls you onto a roof and the creepy toddler who demands a toll.

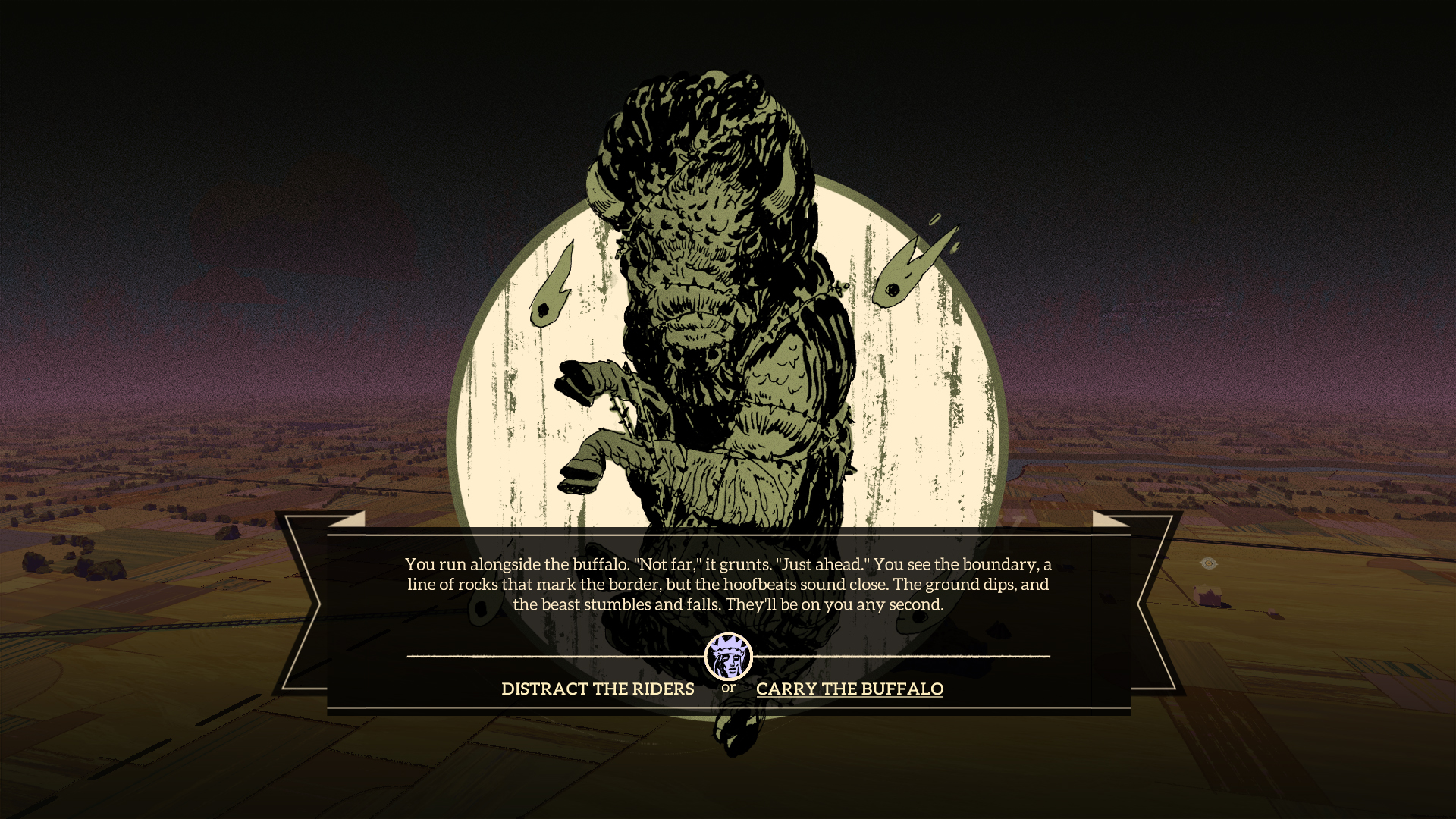

Whether mythical or not, there's some lovely, tragic prose tucked away in Florida and Idaho and California and Oklahoma and elsewhere within WTWTLW's broad map. The best of them involve choices. In one I recall vividly, a trapped baby buffalo begs for help as hunters approach, explaining that they must chase him, and he must run, once a year, every year, to save his kind. I pull him out of a wire fence and run with him. He falls. I pick him up and carry him. The hunters are on me. I fall, hurling the buffalo to the finish line, and they're gone. That's about as complex as the stories get—five or six passages of narration and dialogue—but the writing is dense, and the human, animal, and ecological suffering is violent and striking.

Of all these encounters across hours of play, though, only a dozen or so remained with me. The others I collected for the sake of collecting, to pad my library—where my tales are sadly reduced to progression tokens, in a sense—so I could hear WTWTLW's bigger stories.

Campfire stories

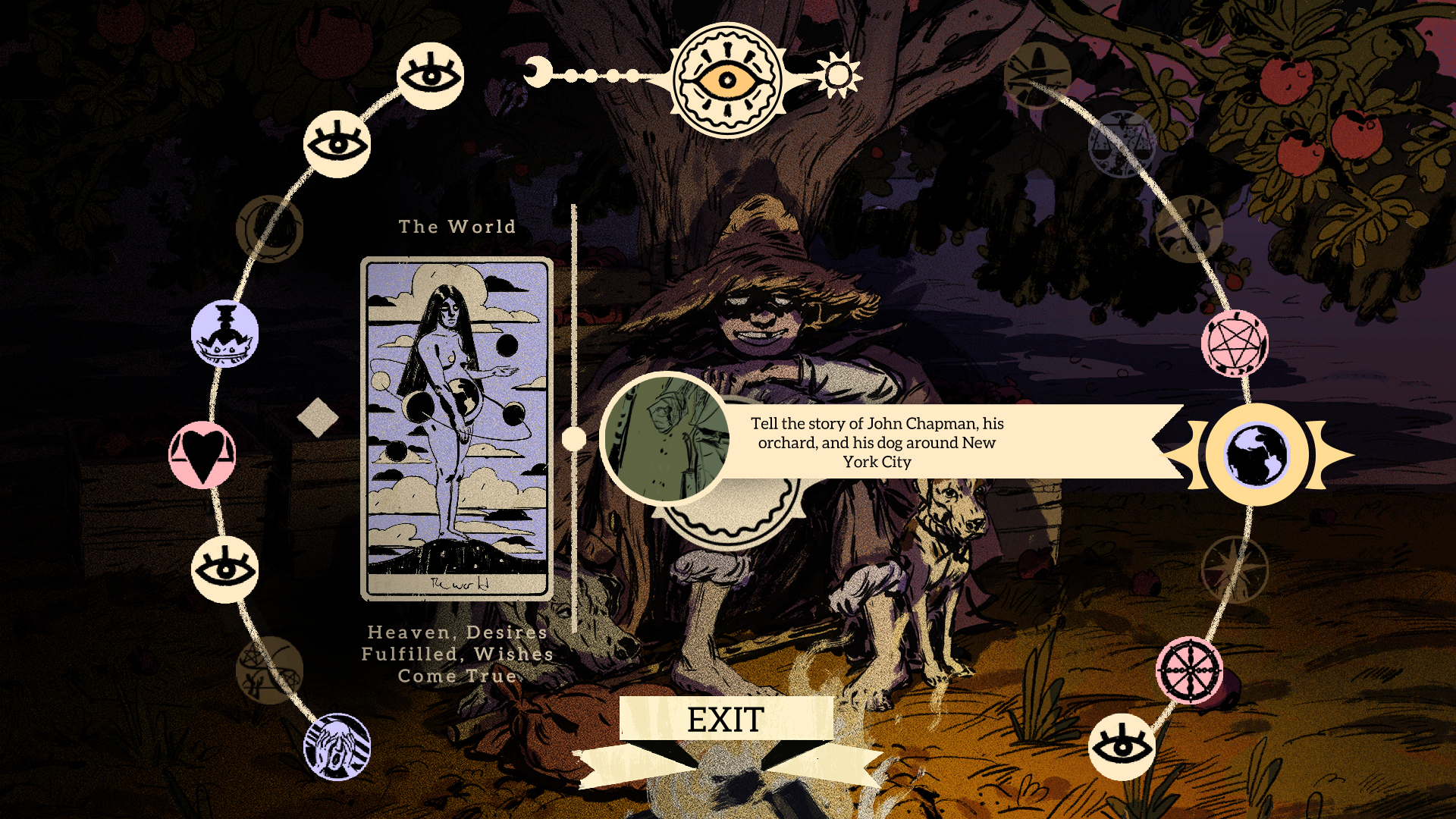

Those more substantial stories, about farmers, coal miners, hippies, preachers, and grifters, come from fellow travellers you'll meet and camp with along the way. As you warm by the fire, they'll ask you to tell them certain types of tales (tragic, scary, exciting, hopeful, funny) that you can pull from your collection of encounters, and after you do so they'll tell you something about themselves related to its themes.

Tell them the kinds of stories they want to hear—which is sometimes obvious, sometimes an annoying crap shoot, especially when it comes to 'funny' stories—and their 'eye' will open. Fully open it (which becomes rote once you have enough stories and know roughly how they're taken) and the next time you run into them a state or so away, they'll have new responses, eventually over the course of several encounters admitting their truths.

These characters, which were each written by a different author, often feel general rather than specific at first. A dustbowl refugee camping outside of LA, for instance, tells me that "the first thing the big owners did was shove the tenant farmers off their land with tractors," plainly recounting a historical detail. Repeated aphorisms can also suppress characterization at times, but stick with them and their stories and personalities shine—especially The Beat Poet (Matthew S Burns), The Sharecropper (Gita Jackson), and The One Who Went Upward (Demian DinéYazhi').

Their role in history still takes precedent, though, and what emerges is an overview of experiences, in which representatives of the Reconstruction, World War I, Jim Crow, indigenous struggles, labor struggles, and the Summer of Love appear in one-person plays to explain how they fit in, drawing from, among many others, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck, Dee Brown, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Lucy Parsons, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg. It's not exactly 'magical realism,' a particular genre developed in Latin America, but a condensing of collective history and literature into mythological individuals to create 'American Gods'—as in the Neil Gaiman novel, except gods of the exploited and oppressed.

The stories are honest and biting reminders of the cruelty of America's past and present. It's a valuable overview, though it's muddled by its confusing attention to the supernatural—which isn't to say the supernatural stories are bad, just incongruous, as they don't serve to undermine America's founding myths, which is what I'd expect. They instead suggest to me a native magic at work beneath it all.

The destination

And as I've lamented, it's way too damn long. WTWTLW's non-written world is special in ways, but not so special that I wasn't tired of it by hour five, and absolutely done with it by hour eight, at which point I had three more hours to go. When the map's wheat fields and colorful clouds align just so, it has a mean handsomeness, but it also ran terribly for me, stuttering often, with visible, jagged seams wearing on my eyes. And once a swath of map has been cleared of encounters, all that's left to do is chase down the campers, slowly treading territory you've already seen to find their next campsite—occasionally contending with bugs, such as when I took Route 66 west and it deposited me in Kansas. It's a rare game that slows down the more of it you complete.

The illustrations have been attacked by hard strokes of black coal as violent as the characters' lives—no complaints. The soundtrack on its own is fantastic, too, though after hours of exploring it fades into the background, just white noise, dampened by my constant whistling. Keythe Farley's narration is also impeccably commanding, and the individual characters' voice acting is superb, but I usually just wanted to get on with it, as they tell their stories so slowly.

Some of those stories are beautiful, and they're all important—as reminders, at least, of the stories we should seek out to understand history, to answer Bertolt Brecht's questions: "Every page a victory. Who cooked the feast for the victors? Every ten years a great man. Who paid the bill?"

In striving for that, WTWTLW is a graphic novel I'd wish to own. As it is, though, I fear that few will venture to its faraway end. I've never had a short story anthology work so hard to keep me from reading its stories.

There are beautiful and tragic scenes, songs, and passages to find in WTWTLW's journey, but they're spread far too thin.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.