When are game companies truly being anti-consumer?

What is true anti-consumer behavior? We break down platform exclusivity, preorders, loot boxes, downgrades, and more.

As gamers we have a knotty relationship with the industry that produces the things we love. With games, we’re unusually dependent on game companies to let us play the things we buy. The days of purchasing a game on a disk and playing it whenever and however we want are long gone, and today we often have to buy into services, the data installed on our PCs is managed by its makers through updates and patches, and our access to it is limited by EULAs and DRM.

There are some upsides: The idea of games-as-a-service has led to vast, rich online games that are constantly updated and improved upon. On the other hand, our pastime is in the hands of large companies more than ever before. If they choose to stop supporting a game, we might not be able to play it any more. If they change how a game plays in ways we don’t like, we can’t go back to the old version. Game companies frame buying their products like joining a community—a family—adding strong emotions to the process of buying a game. Understanding the concept of consumer rights is both more important than ever and also more complicated, and it’s easy to feel powerless and frustrated, especially when the conversation rarely extends beyond 'voting with your wallet.'

When should we be loud, and how should we complain? When is a business practice truly ‘anti-consumer?'

"If you expect a company will have your best interests at heart, I think that would be a bad expectation," says Ira Rheingold, executive director of the National Association of Consumer Advocates. Rheingold is a fighter for rights beyond what we buy: He's testified to both houses of Congress on various finance and mortgage lending issues, and previously worked in housing and welfare advocacy. "You need to recognise that these companies are mostly about making money. They want to create products you’re going to enjoy and to keep you satisfied, but I think it's very important for consumers to be loud and complain when they’re not satisfied, because companies will respond to reputational risk."

But when should we be loud, and how should we complain? When is a business practice truly ‘anti-consumer?' We’re going to look at some of the flashpoints of the modern game business to see when companies are truly being shitty, and when we should expect and demand change.

Platform exclusivity

The Epic Game Store is one of the hottest zones for accusations of anti-consumer practice in the game industry. The broad argument is that by snapping up games and preventing them from being sold on other storefronts, Epic is restricting consumer choice over the platform we play them on.

But if the core of anti-consumer practices are those which leave us less well off with worse products available, I’m going to suggest that the Epic Game Store is broadly pro-consumer.

We’ve directly profited from the key practice Epic has employed to establish the Epic Game Store at large scale: So far, its weekly giveaways have granted us nearly 100 games with a total value of over $2,000, for free.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Epic is more generous than Steam with its revenue split, with developers getting 88/12, compared to Steam’s base split of 70/30. The knock-on effect for gamers is that developers enjoy higher profits that they can reinvest in development. And while Valve still hasn’t budged on its split, it’s having to justify it like never before, actively adding features to Steam at a brisk pace. When developers get more money or better tools, they make better games.

And Valve apparently welcomes the competition. Gabe Newell told Edge magazine: "In the long term, everybody benefits from the discipline and the thoughtfulness it means you have to have about your business by having people come in and challenge you." Rather than fret about exclusivity, Newell is more concerned about the walled garden of Apple's App Store.

The exclusives on Epic's store are still accessible to anyone who owns a PC, and they don't last forever. It’s definitely inconvenient that PC gaming has been further splintered by yet another platform that you have to install, and publishers never should've made exclusivity deals when their games had already been promised publicly for Steam. But generally speaking, consumers have benefited from the Epic Game Store’s arrival.

Most refund policies are already more generous than the law

Platforms already have refund procedures which are usually better than consumer rights anyway, and that’s because the game industry is very public-facing.

Peter Lewin

In most countries, laws give fundamental rights over stuff we buy. A concept called "merchantability" ensures that a thing you bought works for the purpose you bought it.

Trouble is, in the digital sphere you give up on some of the rights you automatically get for physical items. You don’t own games, you license the right to access them in ways defined by the terms of service you’ve signed, and most remove their makers from the responsibility of ensuring they function.

This is partly why lawsuits against buggy games get thrown out, especially in the US, though there’s ongoing litigation by the law firm Migliaccio & Rathod against Bethesda Game Studios for refusing to issue refunds to purchasers of Fallout 76 who claimed technical problems rendered it unplayable. I’d love to know what’s happened since it kicked off in late 2018, but since the litigation is live, they couldn’t comment on it.

For Rheingold, though, law only goes so far in the US, especially under the current business-friendly administration. "You can’t get past the fact that our courts are being pushed to be much more protective of corporations," he tells me.

In Europe, though, laws are more progressively on the side of consumers. In October 2019, the UK’s Consumer Rights Act was amended with new rules which raise consumer protections for digital content. If "faulty" and within 30 days of purchase, you get a refund.

What’s faulty? The basic requirements are that it’s of satisfactory quality, fit for purpose, and as described by the seller. Does it count for buggy, kind-of-functional games? The UK government’s example, of someone buying an item and it failing to appear in their game, is much more clear cut than a lot of real-world gaming situations, like the nuances of troubleshooting GPU compatibility. Future legal cases will help establish those definitions.

But do they even matter? "I don’t know how much benefit consumers get from consumer rights laws anyway, because if I’ve got a faulty videogame, it’s not like I tell Steam I want compensation under the Consumer Rights Act," says Peter Lewin, senior associate at UK-based legal firm Purewal and Partners.

"These platforms already have refund procedures which are usually better than consumer rights anyway, and that’s because the game industry is very public-facing. Companies want good relationships with their consumers, so if a game is broken, quite a lot of the time publishers will give refunds."

Most storefronts, from Steam to GOG, offer no-questions-asked reimbursement, giving you the chance to test a game for a few hours to see if it meets your expectations. With a disastrous game launch it’s often the game company, which has sunk millions on development and marketing, that comes out worst. They have many reasons to fix their game and satisfy their customers. In that context, rather than anti-consumer, most buggy disasters are merely disappointing.

Are 'downgrades' or misleading ads anti-consumer?

Another reason games are deemed anti-consumer is when they don’t live up to pre-release claims and footage. This is an annual cause for anger: Watch Dogs, The Witcher 3, and Dark Souls 2 were all criticized for being 'downgraded,' just to name a few. This has even inspired lawsuits, like one against Take-Two for launching GTA 5 without its online mode (it came a whole two weeks later). Remarkably, the case got to federal court before being shot down.

The classic example is a case against Gearbox and Sega, which claimed they’d falsely advertised Aliens: Colonial Marines in trade show demos. Concluded in 2015, the case kind of fell apart through legal technicalities, though at one point a $1.25 million settlement was on the table.

One of the obvious nuances here is that games change through development; from Spider-Man’s puddles to The Witcher 3’s foliage, decisions are made for technical necessity or aesthetic opinion. It’s difficult to draw a clear line between changes that naturally happen during development and cynical acts of deception.

It’s reasonable to expect a company to be transparent about changes, both potential and actual, between how a game’s been previously presented and how it’s shaping up for launch. One positive result of ‘downgrade’ controversies has been that game companies are now a lot more careful to point out that footage of an unfinished game is just that. Complaining helped, but we do need to take those disclaimers seriously and be critical of what we see. Don’t give companies the benefit of your doubt.

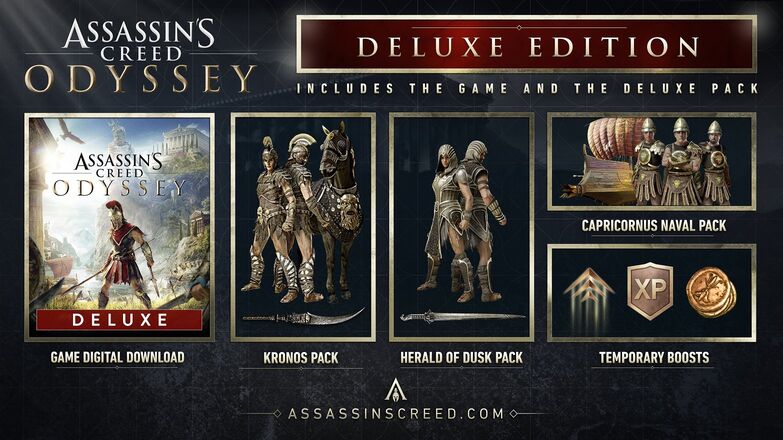

That principle extends to preorders. Many games offer preorder bonuses, but it’s useful to look beyond the free stuff and recognise them as a consumer-hostile practice, because they’re there to tempt you into buying blind. Preorders which offer exclusive items are particularly questionable because they prey on our susceptibility to scarcity. Is gaining a trinket really worth the risk of finding out a game isn’t what you expected it to be? The mitigating factor is that, these days, it's often possible to get a refund—do make sure of that before pre-ordering anything or buying a 'founder's pack,' though.

Gambling and addiction

We’ve seen a great victory for consumer rights around gambling and loot boxes. In response to consumer uproar and new legislation, they’ve been stripped out of many live games, from Destiny 2 to Rocket League, Overwatch to Forza 7.

But the wider concept of games profiteering from psychological tricks remains. Right now, a Montreal law firm called Calex is leading a class action against Fortnite. "Epic Games, when they created Fortnite, for years and years, hired psychologists—they really dug into the human brain and they really made the effort to make it as addictive as possible," attorney Alessandra Esposito Chartrand told CBC News.

The case argues that Epic has the responsibility to warn its players—especially children—of the risks of addiction. Research hasn't established any clear proof that games directly cause psychological problems, though one researcher has told me that 0.2% of individuals use games in a way that’s "maladaptive." But we should demand all games that are popular with kids be highly sensitive to the way they promote and give access to paid content.

Even when lawsuits over gambling fail, they help to discourage companies from supporting or being complicit in exploitative enterprises. For example, Valve has been accused of profiting from third-party gambling systems that rose up around CS:GO. Although Valve did not create skin gambling, it benefited from general Steam Market activity, making 5% (with a minimum fee of $0.01) from all Market transactions. Many cases around gambling have been dismissed but new ones keep popping up, and while the skin sites are the direct problem, they can only operate on Valve's APIs.

Privacy matters

A rising issue around all online media, from Facebook and Google on down, is privacy. And games routinely gather surprisingly detailed information about you.

"What a game can collect is essentially infinite," Joe Newman tells me. Newman advises technology companies on privacy, having previously worked at EA and Ubisoft. For several years he’s been warning the industry that while mining player data can do lots to make games better, it comes with a lot of new responsibility.

For an idea of the depth of data game companies can collect, here’s what a FIFA player got when he requested his data from EA under GDPR: Customer support call recordings, device information, play statistics.

What’s fair to collect? For Newman: "It’s a question of what a game actually needs and wants in order to provide its service, and that varies hugely by game."

Companies are legally required to tell you what data they collect about you in a game’s privacy policy. Unfortunately, that means you have to read one, and they’re often difficult to understand. But Newman says that opaqueness isn’t an attempt to mislead you. "Writing them is a really tricky, complicated balance, because you want to be as clear as possible, but you also can’t afford to miss anything."

If there were a company... manipulating loot box outcomes based on players’ individual propensity to spend, that would be really anti-consumer

Joe Newman

Fortunately, privacy protection laws are strengthening, led by the EU’s pioneering GDPR. Most companies want a single global policy, and that means conforming to the strongest rules, so they work with GDPR as a baseline. And starting with the California Consumer Privacy Act, which came into effect at the start of 2020, US states are following suit.

But it’s difficult to say all this is enough. While companies will say your data is anonymised, it’s been clearly demonstrated that it’s possible to recognise individuals from just a few attributes. And no company can promise it can safely hold your private data. Hacks happen.

And the potential for misuse of data is vast.

"Most companies are doing this in pretty transparent or pro-consumer ways," says Newman. "But if there were a company—and I’m not aware of one—manipulating loot box outcomes based on players’ individual propensity to spend, that would be really anti-consumer."

In this shadowy world, our nature as consumers becomes complicated: Our data can become the product. It’s vital we read privacy policies, discuss, question and hold game companies to the highest values.

Knowing when to fight back

There'll always be some tension between game publishers and game players. We want as much as we can get for our money, and they want as much money as they can get from us. As we've seen with loot boxes, the only way to deter exploitative behavior is to push back—not just by 'voting with our wallets,' but by being loud about what we don't like.

If loot boxes completely fall out of favor, which they seem to be, there's no doubt game publishers will come up with creative new ways to make money. And if those new methods are manipulative, restrictive, or invasive, we should push back against them, too. We've got to pick our battles, though, distinguishing between things that are annoying, like Epic Game Store exclusives, and things that are truly hostile.

All of the topics in this article are complicated and there are always exceptions, but to recap, here are some of the main problems gamers are dealing with today.

- Games can naturally and necessarily change during development, but if we watch trailers and marketing with a critical eye, we won't be caught off guard by misleading footage or missing features.

- Store exclusives are inconvenient for us, but usually that's about it.

- Unreasonable regional pricing can unfairly affect some players without being obvious to others. It's useful to call this out if it's happening in your region, or boost the voices of underserved regions.

- Pre-orders remove your ability to fully judge a game before buying it, and pre-order incentives are often designed to capitalize on players' fear of missing out. Make sure there's a refund policy in place.

- Season Passes offer a small savings, like pre-orders, to get you to spend your money before seeing what you're buying. If DLC isn't also offered a la carte, it's worth calling attention to.

- Gacha games and other loot systems take advantage of compulsive behavior. We'd rather not see them in anything.

- For big 'games as a service,' your time investment and personal data can be as valuable to the company as cash, and make you easier to sell things to in the future. This is probably the biggest ongoing issue we face, and it will only get more complex and important.