What I Learned about VR at Oculus Connect

Insights into what's coming in the world of VR from Oculus Connect

The thing about virtual reality is that it’s hard to describe to people who have never experienced it. Imagine something awesome that you’ve never experienced, and is wholly subjective. It’s similar to trying to describe the effects of drugs or alcohol to people who have never tried them. Sure, you can describe the effects in a technical and medical manner: dizziness, possible nausea, euphoria—but you can’t tell them about what life’s like after two and a half whiskey sours. That part is subjective. In much the same way, you really have to experience VR to get it. That experience is up to the wearer.

My first VR experience was with the humble little Google Cardboard, just a little over a year ago. I was surprised that a simple Android phone could create an immersive experience that vivid. When I tried the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, both products blew my hair back in terms of image quality. The Samsung Gear VR, while really not much more than a really, really fancy Cardboard headset, offers better interface controls and optics than Google’s corrugated paper solution. That’s not to say it’s not breathtaking, but the Gear VR is notably less awesome than its bigger brother, the Rift. However, at $100, the Gear VR will offer a very good VR experience with a relatively low barrier to entry (assuming you’ve got a Samsung Galaxy S6).

John Carmack, Oculus's chief technology officer.

The big money—and this is where Oculus is apparently trying to makes its mark—is in the kind of content my mom would consume. That means Netflix and other things that won't necessarily require a whole lot of iteration. Oculus's deal with Netflix (along with the Minecraft deal with Majang) was the biggest business news at Connect, by far. Combined with Twitch, Facebook just got distribution deals with some of the biggest video content players on the Internet.

While the deals with Twitch and Netflix are huge, those are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to non-game content. The two big streaming services, as awesome as they are, still focus on delivering 2D video, within a virtual living room. To some, that may seem like a bit of VR hubris gone too far: Most people can already watch Netflix in their living room. That doesn't mean that Facebook isn't banking on VR being a big thing.

VR Streaming

One of the talks in the first round of sessions at the TCL Chinese Theater was all about streaming VR video. With a hundred or more developers and content makers packed into the movie theater for the talk, it was readily apparent that there are plenty of people who could be working on creating content to stream to VR users. VR streaming seems easy enough on its face, but in reality, streaming VR presents a set of challenges that regular video streaming just doesn't have to deal with.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

David Pio, a video streaming engineer at Facebook gave the talk, and explained the methodology Facebook was using for 360-degree VR video streaming.

More: MAXIMUM PC AND PC GAMER CHAT ABOUT OCULUS CONNECT 2

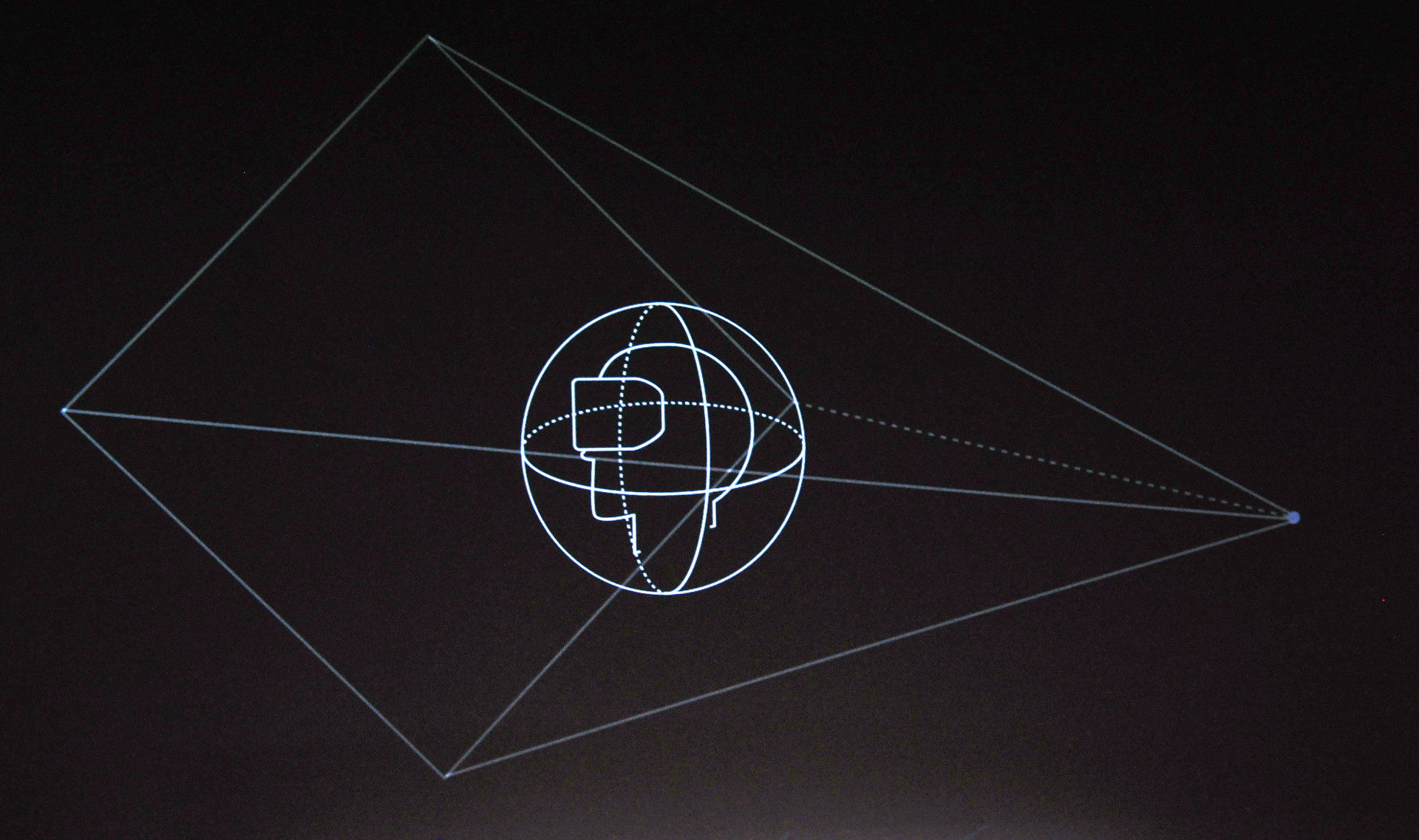

First off, it really helps to imagine what a VR video would look like as a geometric object. From the viewer's perspective, the VR experience should be a sphere, since you can look in any conceivable direction. But since when did cameras capture video in spheres?

They don't.

Instead, software has to stitch together all of these rectangles into a cube, and do a little logical magic to make the video appear as spherical as possible. But that cube has way too much data for the average 5Mb/s Wi-Fi connection, as Facebook put it. To get down to 5Mb/s, Facebook has to compress that video and discard most of that cube.

Pio said Facebook first approached it by lowering the quality of the video out of the user's field of vision and using blurs in the peripheral field of view of the user. They also had to rethink how they buffer video: Instead of buffering 10 or more seconds of video like YouTube does, they buffer one second. That second is looking in one direction, with the other directions reduced in quality. If the headset moves, the video is still visible, but either blurry or at noticeably lower quality. Pio said that this blurry or low-quality video was preferable to having a blank screen when you move your head rapidly.

Luckily, as the headset moves, the movement data is sent back up to the server, which then sends down another second of video, this time looking in the new direction. With the constant polling of headset direction, buffering more than a second of video becomes a monumental waste of time and resources.

Even with the polling and reduced quality cube, there's still too much data flowing down the pipe. Facebook chose to address this by reducing the cube to a pyramid, with the base as the primary, in-focus viewing area. Using a pyramidal shape rids the compression of having to do anything with the "back" wall that the user can't see, and allows some more aggressive compression of the other walls as they are reduced to triangles.

The VR streaming video pyramid.

When the server calculates this pyramid, it unfolds the pyramid and streams the video as a rectangle. The decoder on the client side then re-folds this video into the pyramid and outputs the video to the VR headset. A single frame in the second that is streamed contains the directional data and tells the client how the pyramid was unfolded. The geometry and video polygon location within the streamed frames can change based on head movement, and compression efficiency for a given region of video.

Voilà. VR streaming video that's much closer to the 5Mb/s threshold.

While logically reducing to other geometric shapes—like a cone—has been considered, Pio said that the pyramid had yielded the best performance and overall quality.

While the technical parts of VR video streaming is interesting itself, the implications are numerous. By making VR video "cheap" enough—in terms of resources and bandwidth—it opens the doors for mass adoption of the medium. Imagine live, streaming video where you can be court-side—right next to Jack Nicholson—at the Lakers game, from a hotel room in Boston. Imagine diving on the Great Barrier Reef with researchers from your living room. Those are the types of experiences that become possible with this technology.