What goes into creating a memorable soundtrack?

We talk to composers about the secrets behind our favourite game scores.

This article was originally published in PC Gamer issue 312. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US.

Whether you’re switching radio stations in GTA or trekking across epic mountains in The Elder Scrolls as a choir serenades you, music and games often go hand in hand. A soundtrack can make or break a game’s success, even more so when it’s emotionally and narratively driven. It can tacitly evoke a character’s turmoil or elation, immersing us in the story with a vividness that visuals alone could never achieve.

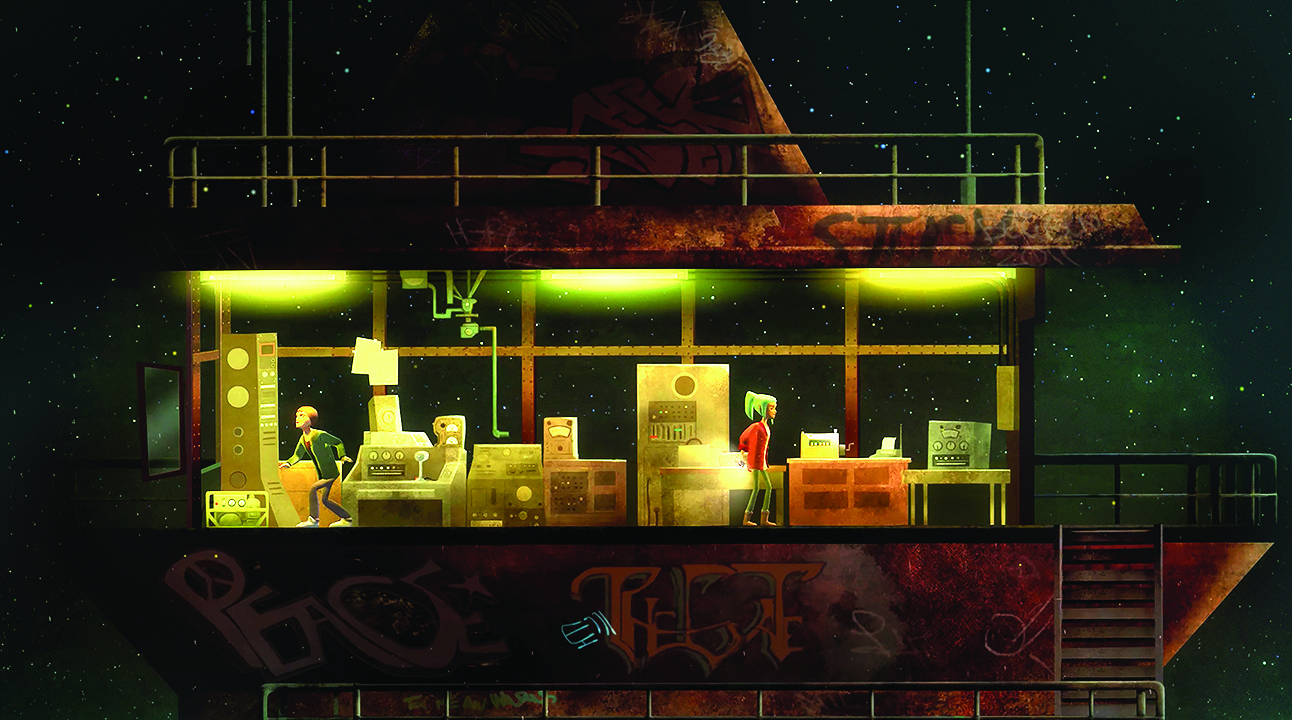

Adventure games have been the de facto example of this. In 2015, Dontnod’s Life is Strange launched, hooking in over 3 million players. Months later, Oxenfree saw Night School tap into the supernatural, while Firewatch was a successful debut for Campo Santo.

All three are considered fan favourites, and while their success is attributed to their storytelling, it’s their soundtracks that have allowed them to flourish. I spoke to the music creators behind these adventures to find out what goes into crafting an acclaimed auditory accompaniment.

“[Musical] scores are 50% of the experience, and I definitely think that with games,” explains Night School Studio cofounder Sean Krankel. “When you look at it, it’s the one part of the game where one vision can come to fruition without too many other things breaking it. In a game, you’ve got mechanics, art, animation, technology, you’ve got all these things that have to work together and if one doesn’t work, the whole system sort of breaks.”

Oxenfree’s soundtrack was created by musician C. Andrew ‘scntfc’ Rohrmann, who pieces together electronic nostalgia with a darkened, brooding intimacy. Depicting a group of teenagers who disturb something ancient and mysterious, the music for Oxenfree needed to feel eerie while also steering clear of horror tropes. “I feel like I was able to find that creepiness in other musical concepts. There’s plenty [of] ‘creepy’ in old recordings, so let’s just really accentuate that sort of thing,” he explains. “I made it a part of the music writing. It wasn’t like ‘music is written and now let’s make it sound old’. Some of that stuff was recorded to 50-year-old tape machines.”

Music in gaming often comes before the story is finished, meaning most music supervisors and musicians have to create a soundtrack from a few key points.

Like a lot of games, Rohrmann didn’t have much to work from in terms of the game itself. Music in gaming often comes before the story is finished, meaning most music supervisors and musicians have to create a soundtrack from a few key points. One sheet of the story and a little bit of concept art was all Rohrmann had to work from, but, as Krankel explains, it allowed the musician to have more of a hand in the design of Oxenfree. “You know those weird tape loop things where you end up interacting with the timeline background track? That was an idea that we had worked on in the creative brainstorms super early on that wouldn’t have been in the game without him,” Krankel says.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“A lot of the game doesn’t sing until everything is in and unfortunately for Andy [Rohrmann], a lot of his stuff comes in last because it’s the stuff that’s supporting the rest of the experience. Andy had to work sort of blind for the first half of the game. He gave us a large buffet menu of a lot of ingredients to work with and it would be like ‘this is thematic of something frightening or melancholic’ just to create tension, and that became this big bucket of tools to work with. Our general aspiration would be, if every second could be scored perfectly to what the player is doing, that would be awesome. But that’s kinda difficult.”

While Rohrmann was able to integrate his musical ideas into the story and design of Oxenfree, Chris Remo didn’t really have a choice. As both a designer and the composer of Firewatch, the Campo Santo team member says it was often difficult to navigate his multiple roles. “When we had to put out the trailer and straight up had to write some music for it, that was so valuable because it gave me this baseline,” he says. “The vibe of the soundtrack ended up changing from that original trailer but it was a starting point and that was incredibly valuable.”

Remo describes Firewatch as “70% to 90% atmosphere,” believing that to be “ideally true” of most games. When embarking on a soundtrack in gaming, Remo says that the crucial thing is to “holistically understand what your game is about”.

“No matter how satisfying a game’s systems are, no matter how gripping the plot is, or how relatable the characters are, plot and characters and world are things that other forms of creative work can also achieve,” he continues. “Game mechanics are very specific to games. The thing that you get when you marry interactive systems and mechanics with those other elements that are not unique to games, like worldbuilding, character, plot and visual representation of those things, the thing you get is a really specific form of atmosphere that is unique to games.”

The Firewatch soundtrack is an almost jarring collection of both acoustic and electronic elements, with the feeling of isolation at its core. Due to its popularity, Campo Santo went on to release the soundtrack on vinyl but, as Remo continues, it was never his intention to have the soundtrack front and centre. “So much of my effort on the game was on the design side and making sure that all of the elements meshed between the story, the game design, the atmosphere, that’s really the point of Firewatch – the marriage of those things,” he says. “So I saw music as more of a tool to achieve that goal rather than a standalone suite of music unto itself. It was important to me that the music never distracted you. This is where being a designer on the game was intrinsic to how the soundtrack worked.”

One team that wasn’t so involved with the design aspect of the game but were intrinsic in securing its success is Feel For Music, which worked as music supervisors on Life is Strange. “A lot of the starting place with that was about trying to get that emotional and human feel to the whole thing,” explains Feel For Music’s Ben Sumner. They nailed this human feel with tracks from the likes of alt-J, Syd Matters and Bright Eyes – songs that evoke that intense navigation of impending adulthood, much like the game’s characters.

“The thing that’s gone down well is the fact it’s different from a lot of other videogame music,” Sumner continues. “The idea of having an acoustic, folk-y type sound, there’s not any other games that spring to mind that have such a strong identity with that kind of sound. The focus on narrative for that game lent itself well to having an emotive, simple acoustic kind of sound.”

Sumner says a lot of the team listened through a lot of the songs while they were making the game, allowing them to test which tracks were working and which weren’t. “They had this drive for it to have a specifi c sound that was emotional. They thought a lot about lyrics and how that played in with the storyline, what happened at the key points in the game and the main characters,” Sumner adds. “Music can be the last thing thought about but the fi rst thing complained about. Some of the best scores are ones you don’t notice, they sit there and help enhance the mood but don’t take the spotlight.”

While the composers and music supervisors on Oxenfree, Firewatch and Life is Strange perhaps never intended for their soundtracks to become as renowned as the games themselves, it’s not surprising that players have formed intense connections to the music. “The thing that you’re left with is this crystallised emotional experience and music is just a huge part of that,” Chris Remo says. “When so much of the value and the emotional impact of the medium does come down to atmosphere and tone, it only makes sense that music is going to mesh with that closely and powerfully in almost a multiplicative way. That’s a powerful thing and I don’t think there’s any substitute for it.”