Our Verdict

Dependence on other players means the game widely varies between completely hilarious and utterly boring.

PC Gamer's got your back

Expect to pay: Free. A subscription for premium content (an additional scenario) costs $7/€5 per month

Release: Out now

Developer/Publisher: Tribe Studios

Multiplayer: Yes (Only)

Link: velvetsundown.com

I gain the trust of Boyle, the bartender, and lead him outside onto the deck of the yacht so we can speak privately. There, I press my taser into his neck, incapacitating him, then rifle through his pockets. Nothing. Boyle doesn't have the secret data I'm after, and he pops back up, furious at the betrayal and spitting profanity. I proclaim my innocence. "It was an electric eel," I calmly explain. He's not buying it. "It was an electric feel," he pouts.

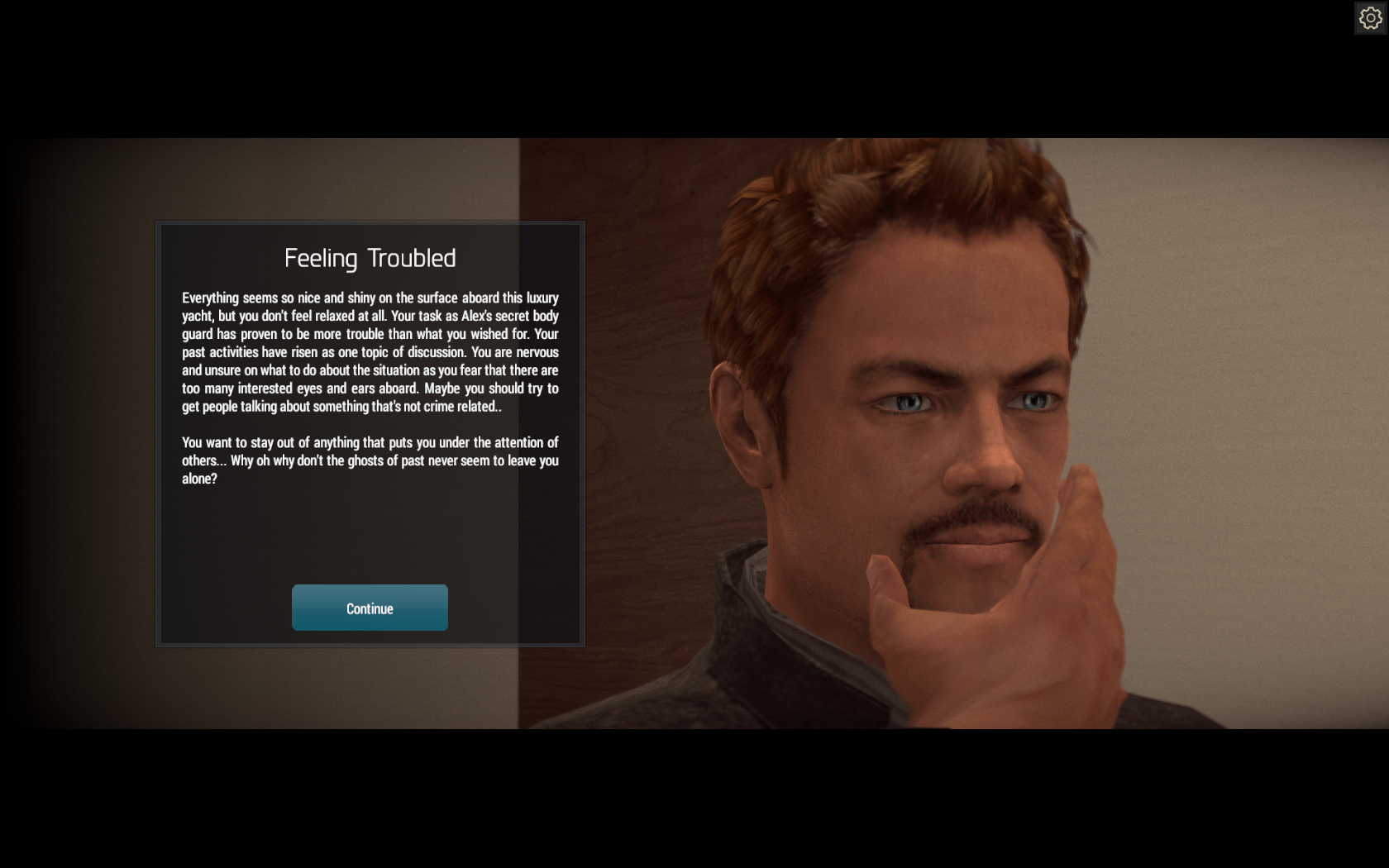

Velvet Sundown is a multiplayer-only role-playing game, where each player controls a different character attending a party aboard a luxury yacht (named Velvet Sundown). Players are given background information about their characters and several goals to accomplish, and have about a half-hour to walk around the yacht and interact with the other players. In one scenario, one character is a journalist, digging for information about illegal drugs, another is a bartender trying to secure funding for a new nightclub, and several others are working to obtain secret data for competing corporations. The dialogue is entirely provided by players typing back and forth to each other, which is translated into amusingly stilted computerized voices by Acapela, a text-to-speech program. (At the time of this review, the text-to-speech feature is only available for premium subscribers, though the developer is working on a way to extend it to non-subscribers as well.)

Some players really get into the role-playing and try to complete their objectives, probing for information, building relationships, and staying in character. Some players are a bit more playful while trying to accomplish their goals. "Put your hand up if you're an undercover agent!" one player announces to a crowd. "I'm not a secret agent," he adds quickly. "I just thought it would be a fun party game." Others have no interest in the game's goals, and just walk around talking to, flirting with, or insulting whoever they meet. As you might expect with players creating their own story, the party aboard Velvet Sundown can get ridiculous pretty quickly.

Flip, rip, and skip the script

In one game, I teamed up with another character, Jack, and we decided to work together to acquire the secret corporate data. It should have been easy: Jack gave me a briefcase containing $100,000 to buy the data with. I decided instead to spend the money—all of it—on a single drink at the bar. The bartender later gave the cash back to me in exchange for a thong someone else had given me, but I lost the money a second time by trading it for the adoption papers for a small child yet another player had offered me. I eventually returned to Jack and explained how I'd lost the buy money twice. He was a little upset.

I laughed a lot while playing Velvet Sundown. With the right crowd, games can be hilarious, and just hearing the computerized voices say the player's ridiculous, often profane, very often misspelled dialogue is good entertainment on its own. Also funny are the awkward animations: saying something like "I like you" makes your character give a rigid thumbs up and using profanity will cause a character to extend a middle finger. A lot of middle fingers sprout up aboard Velvet Sundown.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

When the game doesn't work, though, it really doesn't work. The tutorial, if you can call it that, only teaches you how to walk around and click on things, meaning many games are filled with confused players asking each other how the game actually works. Sometimes players won't talk to you at all, leaving you no way to complete your prescribed goals or even your imagined ones. Icons often appear on your action bar that have no effect when clicked, and no explanation is provided as to why not.

Worse, I've been in several games where players have quit midway through, leaving their characters to remain motionless and inert while the clock slowly winds down. There's no bouncing out to the menu to join a new game, either: even if you quit and rejoin, you'll appear in the same session and have to wait until the round ends before you can join a new one. One session left me with only one other player, and while we tried to amuse ourselves by drinking all the booze (four bottles of vodka), there were still long, dull minutes with nothing to do. A few times I was the only active player left by the end. Other times, you'll just get stuck with unimaginative or uninterested players who just aren't much fun to spend that much time with.

There are currently two scenarios, one being free-to-play and another added through a premium monthly subscription. The pre-game lobby is mostly composed of free players, so getting into a premium match can require waiting a long while. With only fewer than a dozen different characters to inhabit, I became pretty familiar with them and quickly got bored with their intended personas and missions. Not to mention, this being an unmonitored online game, you'll regularly run into players who fill conversations with sexist remarks and racial or homophobic slurs.

Back to my current game, where I've just tazed the bartender. Since Boyle no longer trusts me, I have to act fast. I quickly rejoin the other two players inside. "Don't trust Boyle," I tell them. "He just led me outside and tazed me!" Boyle joins us, a moment too late: no one believes his version of the story. I turn to Mary, another party-goer. "Can I speak to you privately?" I ask. She agrees, and follows me into another room. Zap.

Dependence on other players means the game widely varies between completely hilarious and utterly boring.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.