Valuing games by their cost per hour is bullshit

It's time to stop comparing games as if they're cars with gas mileage.

Trying to decide whether or not you should buy a game sucks. We've never had access to more information about games, but finding the right information is tricky. Reviewers have their personal bias, performance analyses merely tell you if a game runs well, and sales figures only tell you if a game is popular.

Average Cost Per Hour is detrimental because it perpetuates the idea that games are products we consume, rather than experiences we have.

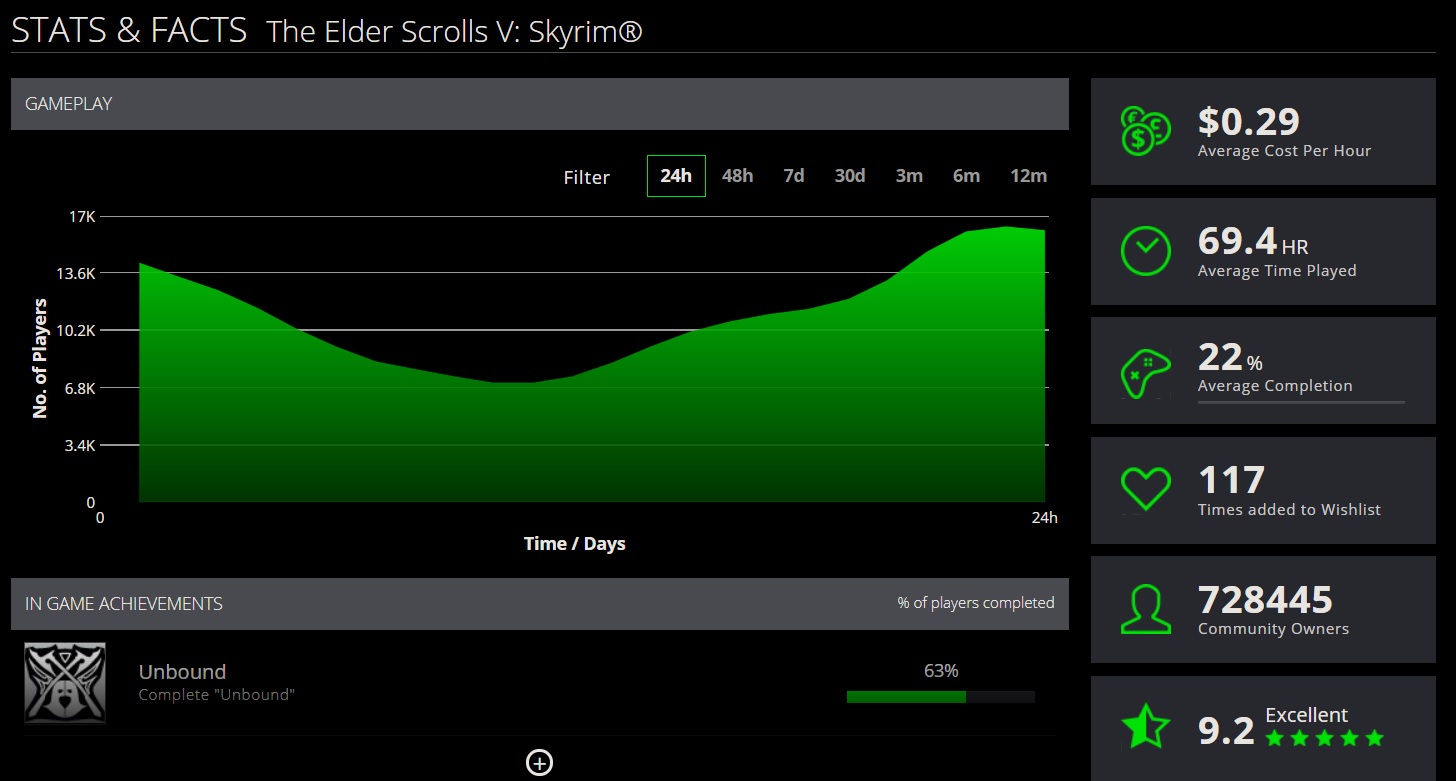

That's what leads platforms like Steam to provide you with as much of this information in-store as possible. Steam Curators, user reviews, and the Steam Community are all useful tools for informing consumers. Last year, retailer Green Man Gaming added several new metrics of its own to better inform customers. Of those new metrics, the Average Cost Per Hour, a stat displayed prominently on each game's page, quickly drew the ire of publishers and developers who argued that displaying this information was harmful to the value of games. The conversation has since returned to the spotlight when, last week, Green Man Gaming CEO Paul Sulyok defended the feature by saying that the stat "allows the community to make informed choices." But when you look at what information this stat actually provides, it becomes obvious how uninformative—and reductive—it really is.

Time and money

Unlike websites like Howlongtobeat.com, which relies on users manually submitting data for how long certain types of playthroughs took, Suylok claims Green Man Gaming creates this stat by taking the price of a game at the time someone is viewing it and dividing it by the average number of hours its own community has played that game. Each user can attach their Steam account to their GMG account, granting the digital storefront access to that person's hours-played data. From there, Green Man Gaming can average those hours across all their users, divide the cost of the game by that result, and create an appraisal of a game's 'cost per hour.'

As a measurement, Average Cost Per Hour is detrimental because it perpetuates the idea that games are products we consume, rather than experiences we have. It enforces the idea that a game's value is derived from how many hours it lasts rather than how meaningful those hours are, and it invites us to unfairly compare games based on how cost effective they are. We're already gaming in a world where concurrent user data is regularly misrepresented as the a true measurement of a game's popularity. It'd suck to see this flawed stat adopted as an objective appraisal of quality in the same way.

If anything, we should be suspicious of how games pad out their length rather those that might be too short.

This isn't just a point of view, it's a widespread rhetoric that has an impact on the design of modern games. It's part of the reason why singleplayer-only shooters with linear campaigns like Wolfenstein are becoming rare while Ubisoft is busy stuffing every one of their games with as many pointless side activities as possible. It's why virtually endless progression systems once only found in MMOs are now used as scaffolding to prop up what would otherwise be much shorter games. If anything, we should be suspicious of how games pad out their length rather than those that might be too short.

Length and price are absolutely worth discussing when evaluating a game, but they need context in order to make those discussions meaningful. Dragon Age: Inquisition's cost per hour, for example, might imply a great value. But consider how awfully paced and drawn out certain sections were, not to mention the abundance of painfully boring MMO-like chores.

One of the biggest problems with this Average Cost Per Hour metric is that it is simply misleading. By displaying it prominently without any sort of valuable context, Green Man Gaming suggests that its accurate when it isn't. There isn't any detailed information as to how the stat is calculated, how accurate it is, or what the margin of error could be. There's no transparency, and it's disingenuously presented as truth when it is far from it.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Green Man Gaming's data doesn't distinguish between owners who've made multiple playthroughs and those who've just purchased the game but haven't played it. It doesn't separate between the time I spent troubleshooting mods in Skyrim and actually playing the damn thing. Hell, it can't even recognize all the hours a game ran idle while I did other things. It also diminishes the impact that short games can have, implying that a two-hour game should somehow also cost $2 just to keep up with the cost per hour ratio of a game like Skyrim.

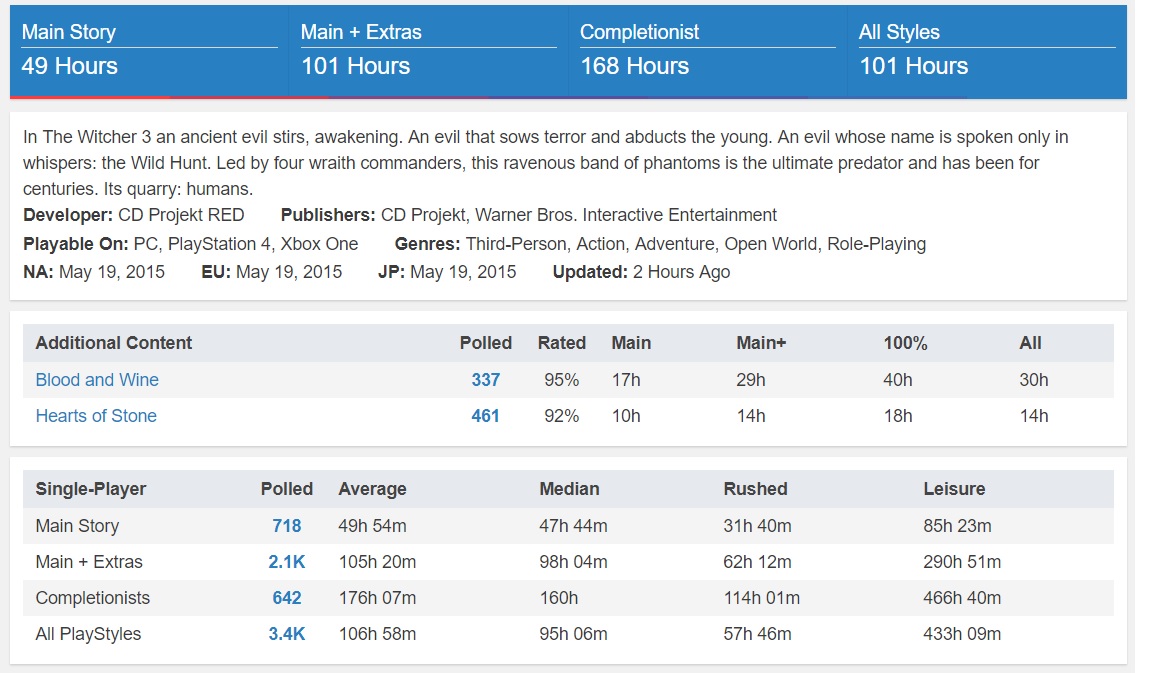

Howlongtobeat.com avoids this mistake by contextualizing its data, breaking playtime down into different playstyles like "Completionist" and "Main Story." When checking Howlongtobeat.com, I can quickly see how long a game will take me to beat if I want to blitz through the main story or, conversely, take my time smelling every flower along the way. It's like pausing Netflix to see how far through an episode you are or checking how many pages are left in a book. How you spend those hours matters, but Green Man Gaming merely averages the playtime across all its users without any of this valuable context.

It's a problem that's annoyingly confined to videogames (and, just to be fair, sex). You're made to believe duration-per-dollar matters when there are many other less tangible aspects that better contribute to a satisfactory experience. You wouldn't measure a book's worth by how much it cost divided by its word count or a movie by its ticket price divided by its length. But for some reason games are different?

This metric only invites apples-to-oranges comparisons between unlike games. The value I got skulking around Rapture in Bioshock ($1.64/hour) isn't comparable to the hours I spend dungeon diving in Pillars of Eternity ($2.02/hour)—each is a fundamentally different experience that provided a different kind of value. And how am I ever supposed to weigh the hours I spent slinging cards in Hearthstone with the time it took to beat Life is Strange? They're completetly different experiences.

It's only natural that we want to compare, as people often do with review scores, but the whole medium is better off if we acknowledge the unique experience each game provides. This is why Green Man Gaming's cost per hour metric is total bullshit, because in pursuit of making its customers more informed, all it's doing is treating games as if they're cars with differing gas mileage.

It's interesting that Suylok defends this decision by saying that Average Cost Per Hour doesn't define a game's value, but its position as the first stat a consumer sees when browsing a game's page sends a completely different message. For some reason, the aggregated user score is the last stat in this column. How does that not imply that a game's cost effectiveness is a more valuable metric than people's actual opinions?

Measuring a thing's worth by how much we spent on it and for how long is a giant step in the wrong direction of understanding its value.

In his interview with PC Games Insider, Suylok said the intention is to help people weigh the cost-effectiveness of games against other activities. But when was the last time you decided to skip a night out with friends because it was more cost effective to go see a movie alone? Measuring a thing's worth by how much we spent on it and for how long is a giant step in the wrong direction of understanding its value. We can't let the fear of disappointment steer us towards a mindset that overly simplifies these experiences as good or bad, worth it or not worth it.

Obviously, you're entitled to assess a game's value however you want—even if that means choosing one game over another simply because it's longer. But this isn't just one person's point of view. Green Man Gaming isn't providing customers anything valuable by breaking games down by their average cost per hour. It's merely codifying a harmful mindset and packaging it up as a feature in an attempt to distinguish itself against tough competitors like Steam. It's a useless, inaccurate stat that perpetuates a damaging stereotype that bigger games are better.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.