Our Verdict

A jog-fest with sluggish combat and inconsistent stealth, but a story that will pull you toward the end anyway.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? An open world stealth and survival game with a linear narrative told across three acts.

Expect to pay: $60/£45

Developer: Compulsion Games

Publisher: Gearbox Publishing

Reviewed on: Windows 10, Core i7-6700K, 16GB RAM, GeForce GTX 980

Multiplayer: None

Link: Official site

Near the end of We Happy Few's first act, I sneaked into a control room to press some buttons, as pressing buttons is how most problems are solved in stealth adventure games. As I fumbled for the correct sequence of presses, one, two, and then three whistling engineers strolled into the room, spotted me, and then bludgeoned me to death.

I reloaded my autosave a few feet away with the same sliver of health I had before and tried again. Once again, a jab to the nostril from the tip of an umbrella evaporated my health bar, replacing it with a red skull which drained slowly until death. The only way to come back from the skull icon is to use a healing item, but I hadn't bothered to craft a surplus from the herbs out in the garden district, so I just had to keep dying and trying.

If I hadn't wanted so much to find out what would happen next in alt-history '60s Britain land, I'd have hit Alt-F4 right there. But finally, I memorized the solution so that I could rapidly press the buttons in sequence and escape with just one fight, barely avoiding a hit to my unprotected skull (should've crafted a helmet, too). It's rare these days that a game punishes me so thoroughly for being unprepared, or pushes me forward almost solely on the merits of its storytelling.

Run for it

I like that We Happy Few, at least on its normal difficulty, doesn't care whether or not I choose to wander its open world crafting healing balms, grenades, lockpicks, fancy electrified weapons, distraction devices, and caltrops before walking into a nest of homicidal scientists. I don't like that none of that is much fun.

We Happy Few's characters are drugged British civilians left to rot after victorious Nazis stole their children. Nebulous hit detection, pathetic stamina bars, and lumbering swings convey their desperation and lack of fitness, but while being pummeled by a mob is thematically consistent, it's graceless and tiresome.

Instead, you can sneak. We Happy Few's stealth puzzles are best when they lightly imitate the item-combining puzzles of classic adventure games. In a newspaper office, for instance, I fixed the coffee machine to clear out an entire room of caffeine-deprived journalists. But that's not the typical experience. The avenues and buildings swarm with erratic, hyper-sensitive civilians and guards and usually only the most tedious maneuvering can avoid conflict—and even then, you may be set upon for seemingly no reason. (Unless your attacker gets stuck in the floor and can't move, which is a blessing.)

When you absolutely must get somewhere to flip a switch (a sibling of button-pressing which also shows up often), We Happy Few takes after Half-Life 2 and throws a heating duct in your path or some pipes to climb for a makeshift catwalk. The rest of the time, a stealthy approach is liable to become a Benny Hill chase, in which the best course of action is to run the mob in circles until you have enough of a lead to round a corner, hide under a bed, and wait out their rage. Cute distraction devices like rubber duckies are occasionally helpful, but for the most part I preferred to just get shit done rather than try to hide from people who walk about like miscalibrated Roombas.

Blending in

We Happy Few lifts the burdens of its own premise as you play.

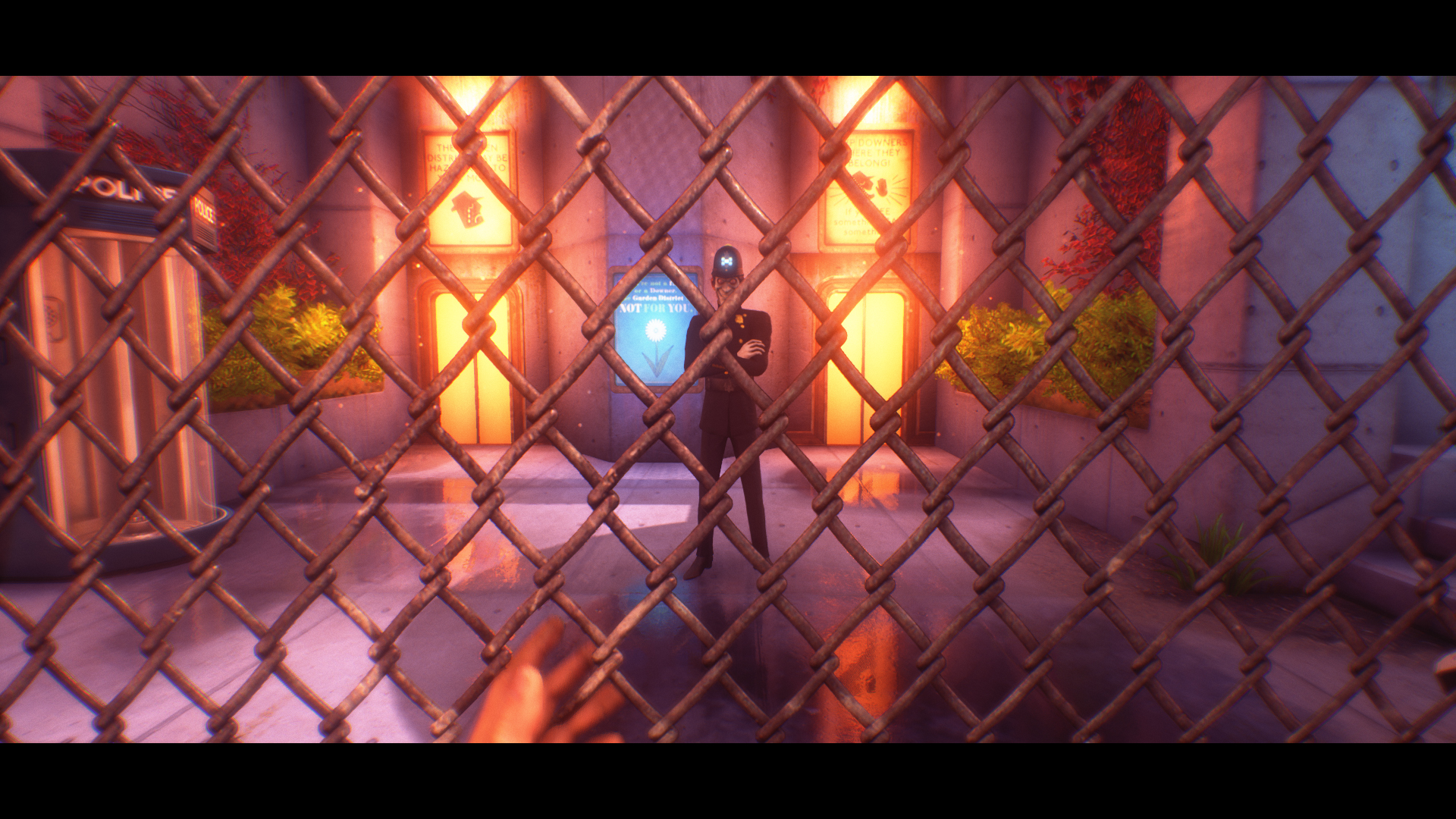

We Happy Few's central roleplaying premise and most novel idea is its least successful. The districts of its oppressed British islands are divided into two categories. In the wild gardens, desperate rejects stand listlessly in decayed roads and hide out among bombed-out buildings. In the middle-class neighborhoods, well-dressed citizens endlessly pop a drug called Joy, which inhibits memory (mainly the memory of giving all their children to Nazis) and reduces cognition to cheerful hellos. The idea is that one must blend in correctly depending on the company. Wear a fancy suit in the wastes, and the populous will tear you apart. Wear a tattered suit on the other side of the gates, and the little old ladies will scream as hordes of bobbies and civilians descend on you.

The wastrels are easygoing. Wear filthy clothes and don't get caught trespassing and they'll leave you alone. In the city streets, however, one must always keep up the appearance of Joy dependency. No running, no jumping, no staring. Pop a Joy, and the bloom effects explode, the rainbow-painted streets glow, and butterflies replace the filth. That's one way to get past the 'Joy detectors,' which raise an alarm should you pass through unmedicated. But if your Joy high runs out, you suffer withdrawal, which near instantly causes everyone in your vicinity to turn hostile. I took to hiding in trash bins while the withdrawal meter slowly ran down, using the time to get up and make a cup of tea. I drank more tea out of the game than I did in the game.

We Happy Few succeeds in making me feel self-conscious all the time—another thematic victory and a funny send-up of the absurd ways players tend to behave in games—but there is no intricate social engineering challenge to any of this, just tiring routines. As you progress, you'll unlock fast travel points and abilities which allow you to ignore many of the rules, letting you sprint around or go out after curfew without issue. Learning to craft Sunshine, a drug which imitates the outward effects of Joy without the withdrawal, is also vital. We Happy Few lifts the burdens of its own premise as you play, seemingly aware that hiding in plain sight in its oversized open world turned out to be a chore rather than a playful test of wits.

Even with fast travel, there's a lot of sprinting, allowing your puny stamina meter to deplete, then walking to refill it and sprinting again as soon as you can. Quests typically involve going somewhere to find something, and so to get anything done in a timely manner, I eventually started ignoring the civilians and Joy detectors. Let them chase! I can just run to my next destination and either hope to trigger a conversation which resets the enraged villagers, or hide and take the opportunity to make another cup of tea while they calm themselves.

A reason to go on

Had I been more content to meander, I might not have minded tip-toeing around to steal food and drink (you won't die without sustenance on Normal, but you'll suffer penalties), lockpicks, healing herbs, and Scotch to bribe bobbies with before I charged into a bludgeoning in that control room. But We Happy Few's greatest strength makes its weaknesses even weaker: I always wanted to see what would happen next too badly to putter around hiding from people who are no more than switches flickering between complacent and homicidal.

I thought I might be put off by the oh-so-British pastiche the way I was by BioShock Infinite's candied Americana: every table is littered with tea cups, everyone is delightfully repressed, and umbrellas are exclusively called 'brollies.' While it's laid on thick—not as thick as in Sir, You Are Being Hunted, but thick—it's occasionally critical enough not to feel totally indulgent and hokey. The heaps of tea, for instance, are paired with a minor side story about Britain's colonization of India. And while it begins with the most wearisome alternate history prompt there is, it's thankfully not about a ragtag team of heroes who rise up to reclaim independence. 'The Germans' are referred to often but never seen. Instead, we find people who were remade as colonial subjects and then abandoned to self-destruct. In the aftermath, they found a way to forget what happened.

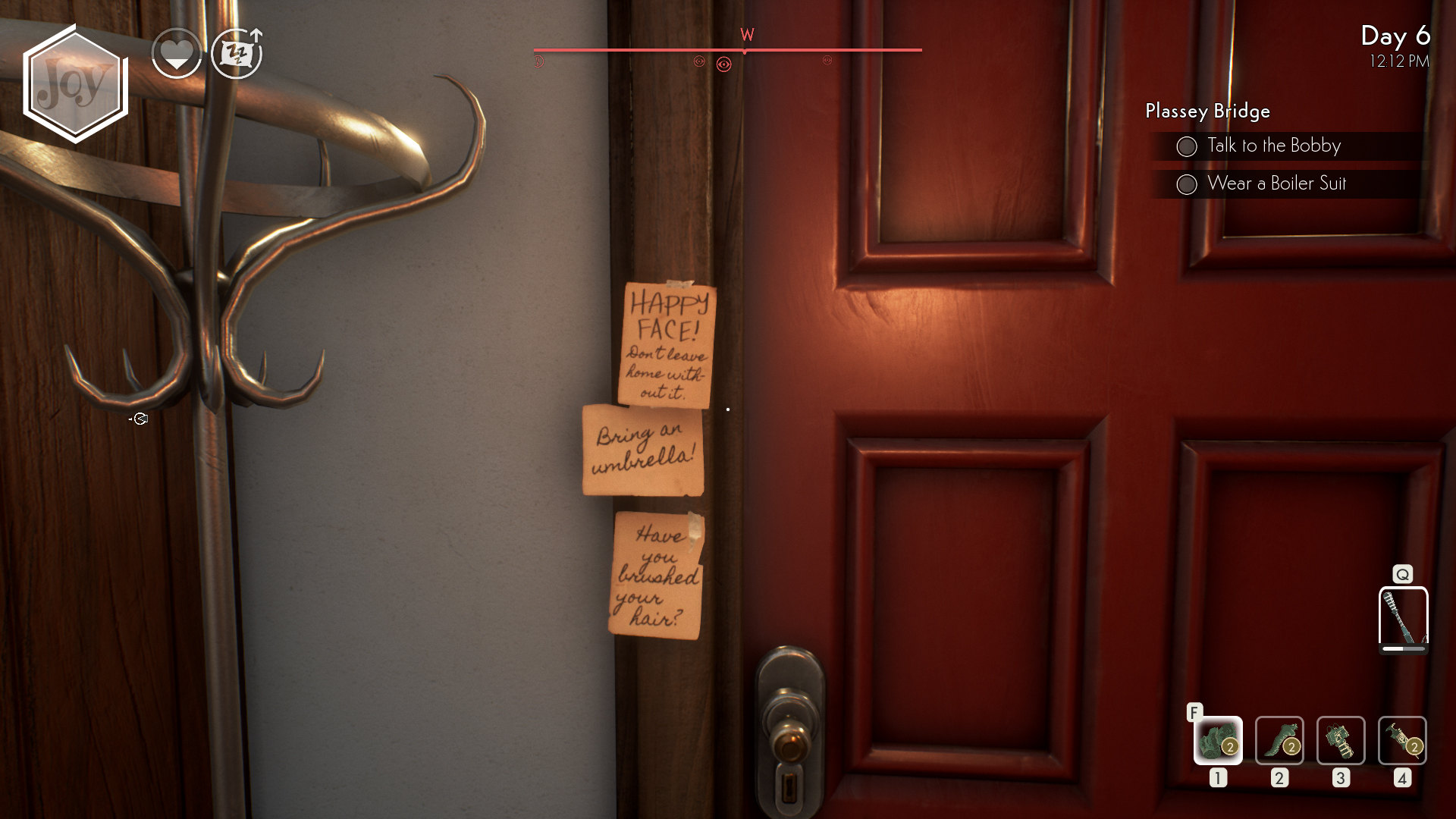

BioShock Infinite's Columbia is a far better put-together dystopia: We Happy Few consists largely of a handful of awkwardly animated character models, repetitive, procedurally-generated city streets (though there are some great details in interiors, especially the notes), and weird bugs like fires burning in the sky. But it outclasses Infinite's storytelling with every line of dialogue.

Across three surprisingly-long acts you'll play as three connected characters. First is Arthur, who's so petty and self-serving that he continues to moan about his old coworkers even after discovering that he's a human test subject in a fascist prison. Then there's Sally, a chemist with a secret, and the supplier of the best Joy in town. And finally there's Ollie, a diabetic soldier who has inconsistent memories about his life's tragedies. Much can be gleaned before it's revealed—it's obvious that Arthur is misremembering his past, for instance—but the flashbacks and conversations are spectacularly voiced, funny, and often heartbreaking. They drew me through a game I otherwise didn't like much at all.

I've also never played as a character who needs to monitor his blood sugar. While Ollie having diabetes and other surprises don't make for especially exciting problem solving (in Ollie's case, collect honey to craft glucose syringes), the focus on human bodies and their needs and limitations bridges the play with the non-interactive acting. It's not We Happy Few's defining success, but it adds to the characterizations in a way I haven't quite experienced before.

Fallen empire

By being so literal with Joy as a drug, We Happy Few plays into the stigmatization of antidepressants.

The performances are We Happy Few's great strength, blending comedy and tragedy with calculated balance. The three lead actors, Alex Wyndham (Arthur), Charlotte Hope (Sally), and Allan James Cooke (Ollie), talk to themselves so naturally that I almost don't notice they were doing the videogame thing of saying everything out loud for no reason, and that even goes for the repeated contextual barks. While there is some exaggeration of character archetypes—Ollie's trauma causes him to hallucinate a child in a manner invented for fiction long ago, Arthur is the quintessential self-serving dope—they are superbly-crafted versions of those familiar characters, with enormous personalities that intensify as they uncover their pasts.

The odd character out is Sally. Her story leads her toward a heroic stoicism that clashes thematically, casting her as the great hope while Arthur and Ollie quest for personal truth—it's unfair and outdated and corny, and can be read as equating her guilt after being abused by men to Arthur and Ollie's guilt after actually fucking up. Taken that way, it's awful, but she remains defiant while suffering that undeserved guilt and a few moments do seem to recognize that she's done nothing wrong. It's confused, at the least. (If it's a sensitive topic for you, note that themes of sexual abuse are prevalent in her story.)

Other characters and metaphors flounder as well. By being so literal with Joy as a drug, We Happy Few suggests that the 'true' self disappears when medicated, playing into the stigmatization of antidepressants. And the recasting of history's victims is ironic, as the theme of We Happy Few is the rewriting of the past to absolve oneself of guilt. The alternate history setup can be read as a meta-commentary hinted at by the text-driven asides about colonialism—an admonishment of Western revisionist history—but it's a soft jab if anything, not some powerfully radical framework. Readers of New York Times op-eds won't feel out of their elements.

Even so, the characters, the acting, and the tragedy were enough to get me to eke what fun I could out of playing the thing. We Happy Few's bugs and inconsistencies and thematic concessions make its open world tiring, survival obligatory, stealth frustrating, and combat clunky, but if you're willing to take it slow and gather lots of herbs and metal bits for crafting, it's worth exploring its mysteries. And there's no shame in playing on easy to quiet the mobs a little.

A jog-fest with sluggish combat and inconsistent stealth, but a story that will pull you toward the end anyway.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.