PC game collecting community rocked by game forgery scandal

An in-depth investigation has revealed suspected forgeries of rare, expensive games including Akalabeth, Temple of Apshai, and many others.

The boxed PC game collecting community is in an uproar over the discovery that a prominent trader has allegedly been selling forged copies of rare, expensive videogames, some of which were purchased for thousands of dollars.

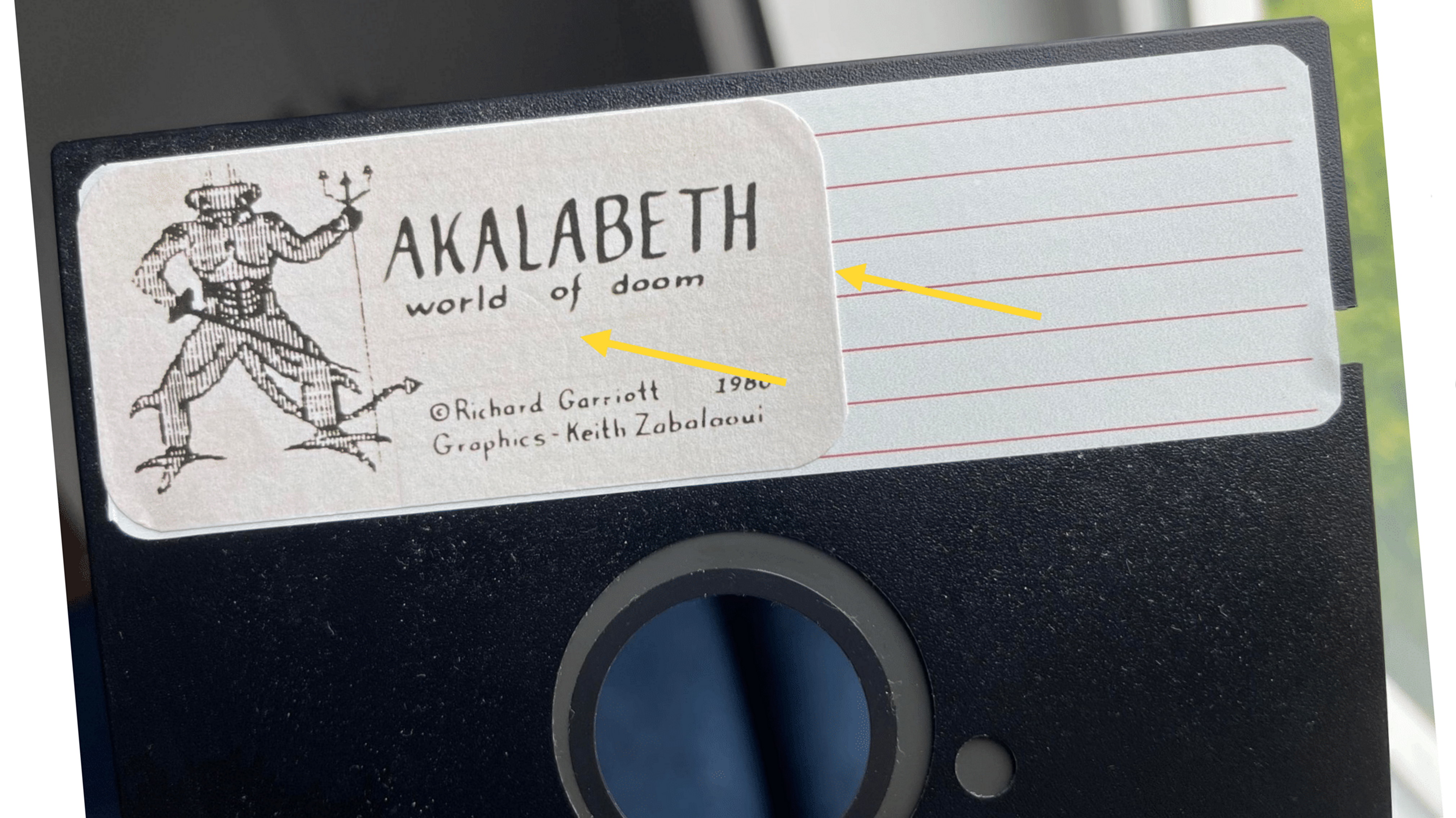

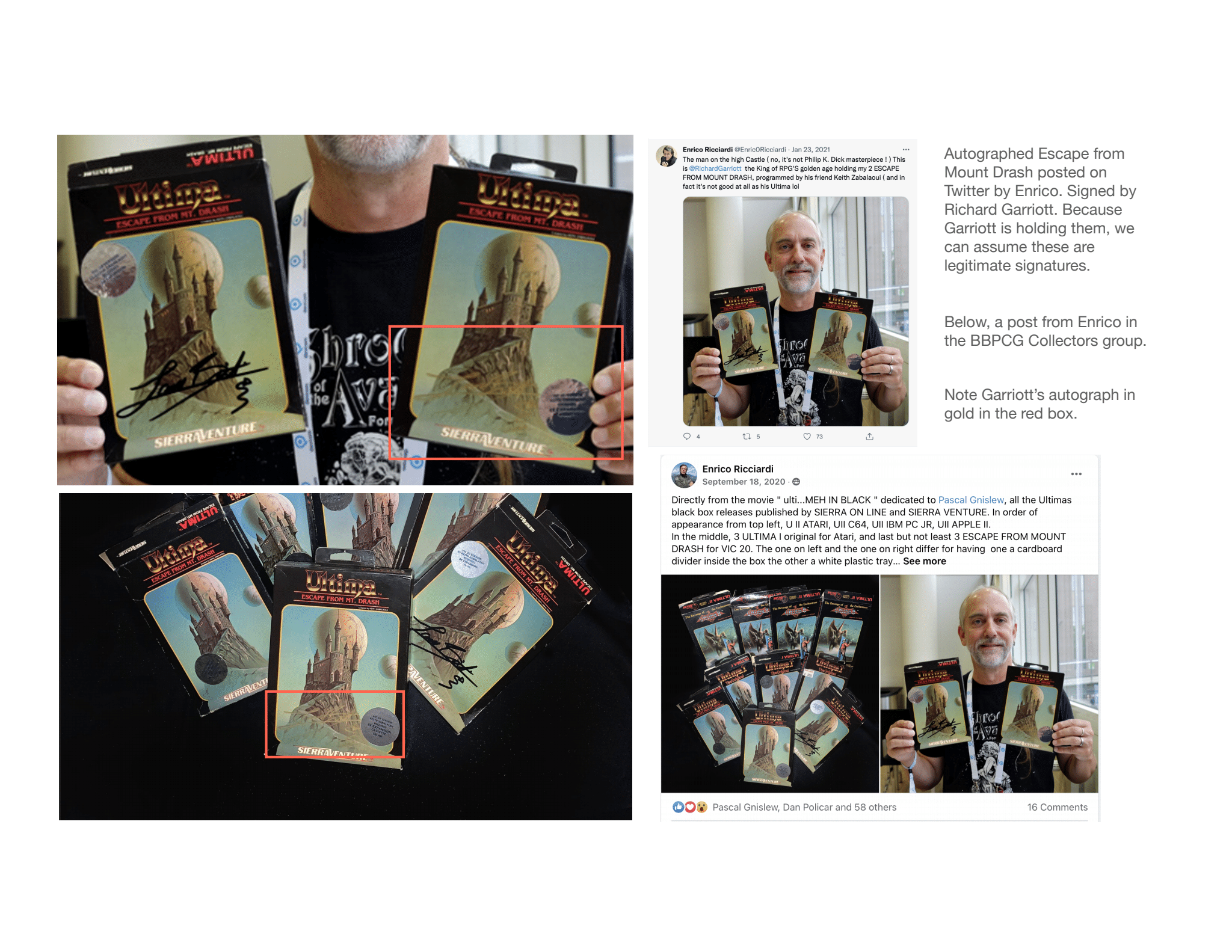

According to a timeline posted on Big Box PC Game Collectors, a Facebook group with roughly 6,100 members (of which I am one), the issue came to light when group administrator Kevin Ng received copies of Akalabeth, Ultima creator Richard Garriott's first game, 1979 dungeon crawler Temple of Apshai, and the Japanese edition of Mystery House from another well-known collector and now former group moderator, Enrico Ricciardi. A close examination of the games revealed that they were likely counterfeit. When confronted, Ricciardi reportedly "alluded" that Akalabeth was indeed fake, and suggested it be destroyed.

Ng contacted other members of the collecting community and found that the problem was widespread: An "exhaustive investigation" revealed that a number of other group members had received what appeared to be counterfeit games from Ricciardi.

Ricciardi denies ever knowingly selling forgeries.

Dominik R., one of the Big Box PC Game Collectors members who believes he was sold fakes, shared images of his Ultima collection, now believed to be counterfeit, on Twitter:

This used to be the center pieces of my collection. Rare and expensive old games.Now it turns out I‘ve been scammed and sold forgeries by a well known figure in the Ultima and tetrogames community. Along with many others#ultima #akalabeth @RichardGarriott pic.twitter.com/wuiAQPSuG2May 30, 2022

This isn't a minor argument across a table at the local swap meet. Copies of rare games can sell for a lot of money to deep-pocketed collectors. In a 2013 Kickstarter for Shroud of the Avatar, for instance, Garriott offered up to 20 copies of Akalabeth as a reward for backers at the $10,000 tier. Nine were sold.

"[Pricing] depends on many factors," a Big Box PC Game Collectors moderator who requested anonymity explained. "Is this one of the original set that Garriott released? Is it a recent new version for the C64? Does it have all its original components in good condition or just the disk? Is it autographed? Does it have established provenance? The answer is $500 to infinity, depending on provenance or conditions."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Big Box PC Game Collectors administrators say they have identified at least €100,000 ($107,000) of suspected counterfeit transactions so far, including full game boxes, manuals, registration cards, inserts, labels, and more. Incidents involving suspected forgeries go all the way back to 2015, and along with Akalabeth, Temple of Apshai, and Mystery House, involve early releases from Sierra and Origin Systems.

Determining a forgery from an authentic game release is a tricky business, involving up-close examinations and comparisons of tiny details in the packaging and media. The group said that one of the biggest challenges in determining authenticity of old games is that production quality varied widely in the early '80s, an era when games were often shipped in ziplock bags with instructions cranked out on old dot matrix printers. "What seems to be sloppy production methods or just photocopied paper in plastic bags was indeed the very beginning of our industry," the group said.

Garriott himself alluded to that difficulty on Twitter, saying that it's possible the games could be legit, "but pirated versions."

Before we all jump and admonish a seller… we should study the items. For example: my sig looks authentic. The “shareware” could be legit… but pirated versions, not sold by Origin or EA. Some ziplock bags look too big, but the Akalabeth and Ultima inside look correct fronts. https://t.co/wCjZHe7ErKMay 31, 2022

The Big Box PC Game Collectors group broke down three "suspected tells" that all of the games in question shared:

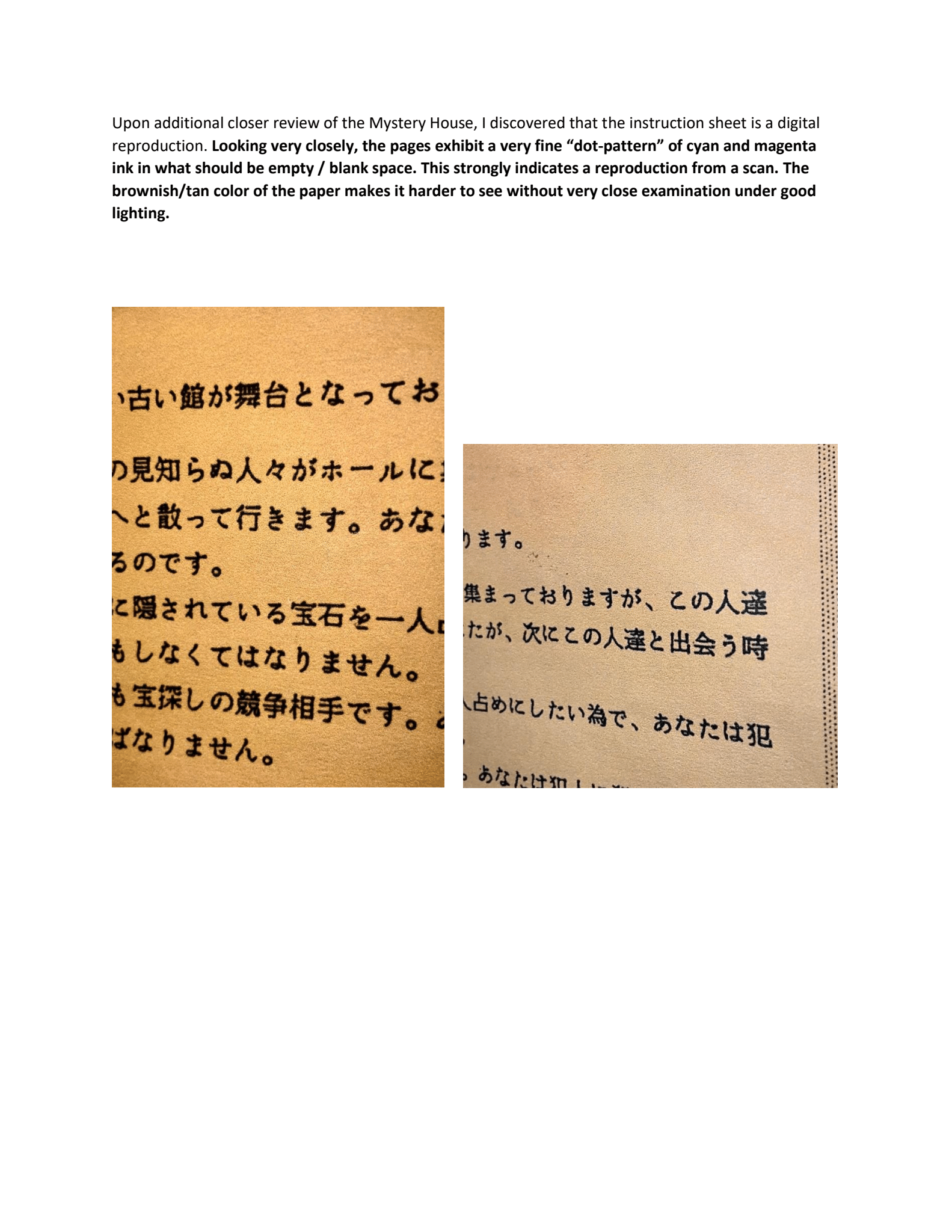

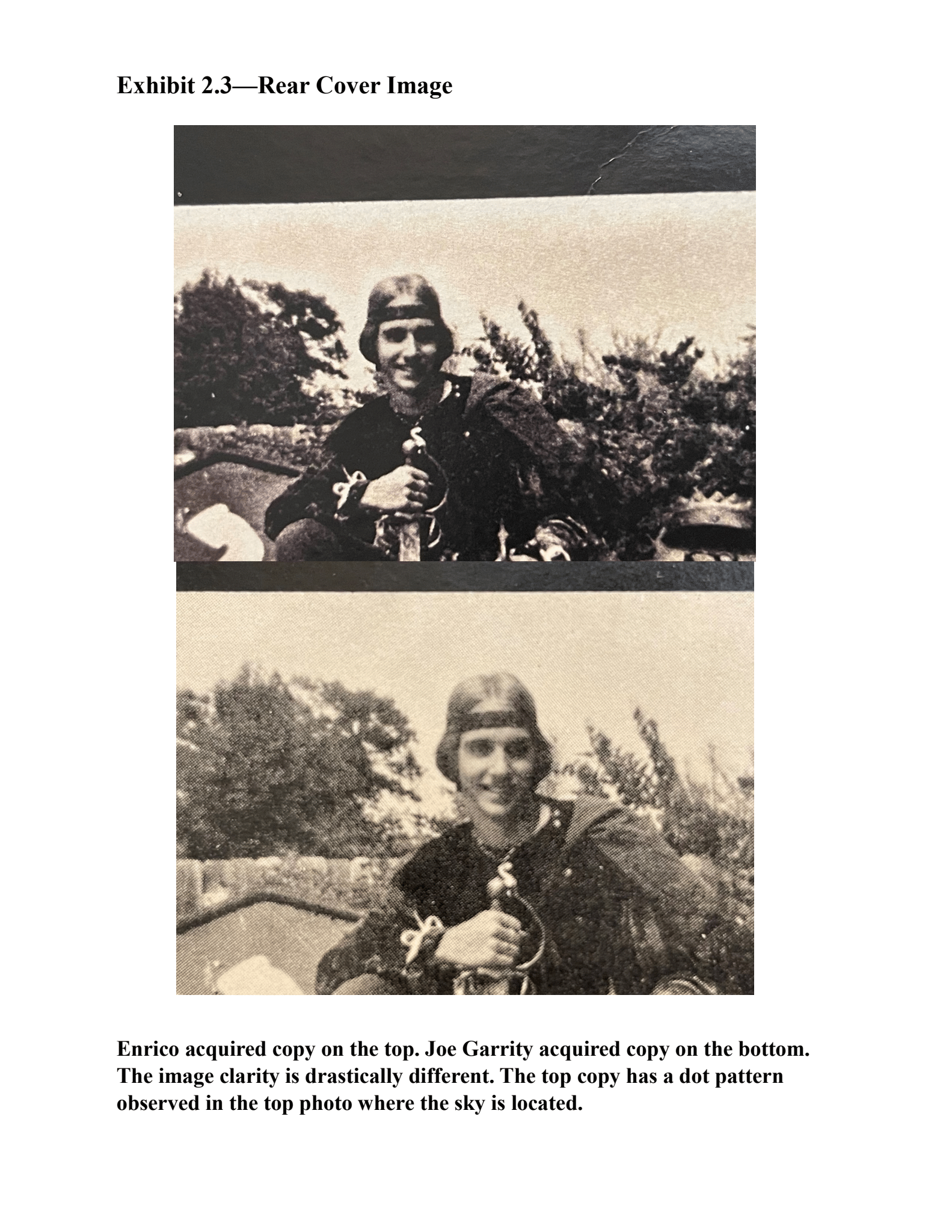

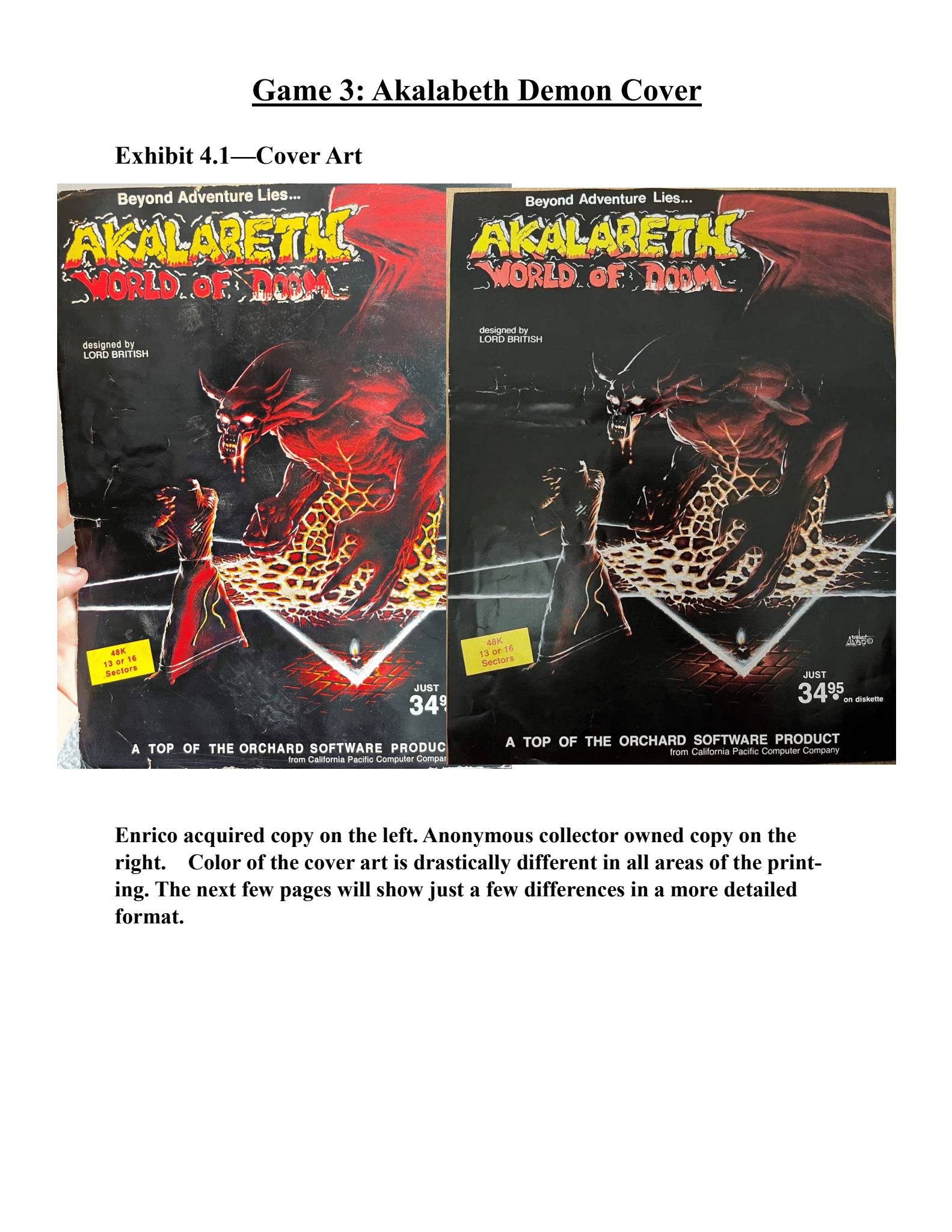

- PRINTED PIECES: The halftone dots on printed materials do not appear to be in-line with print processes from the time. Sometimes dirt and wear appear to be printed on. CMYK dot patterns appear in places where there shouldn't be printing at all. The halftone patterns on Enrico's materials often present a Moire' pattern, which happens when reproducing something that already has a halftone pattern. Things that are supposed to be one color prints often appear to be four color prints, or they don't have smooth edges when looked at closely. Digital manipulation artifacts are present. Colors in general are often different.

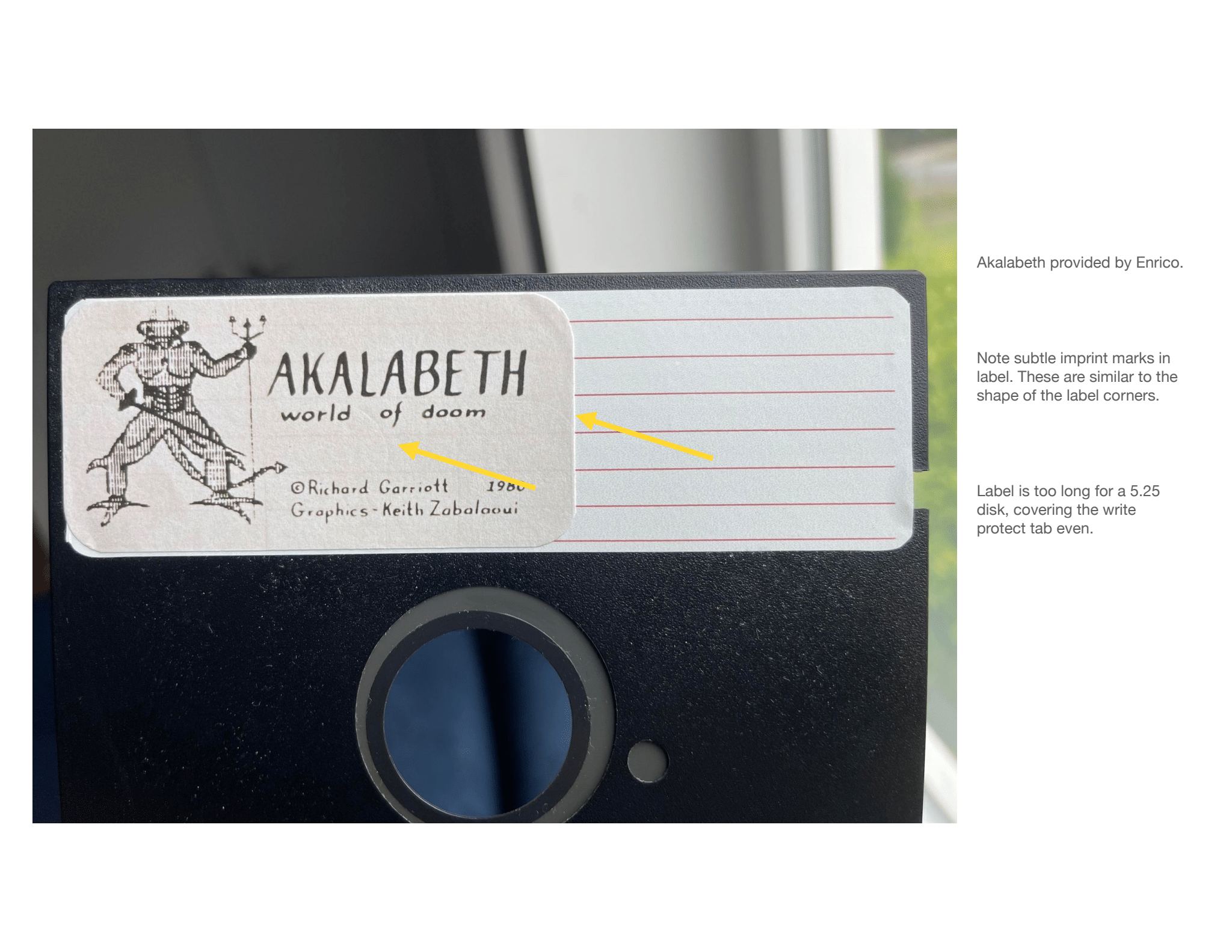

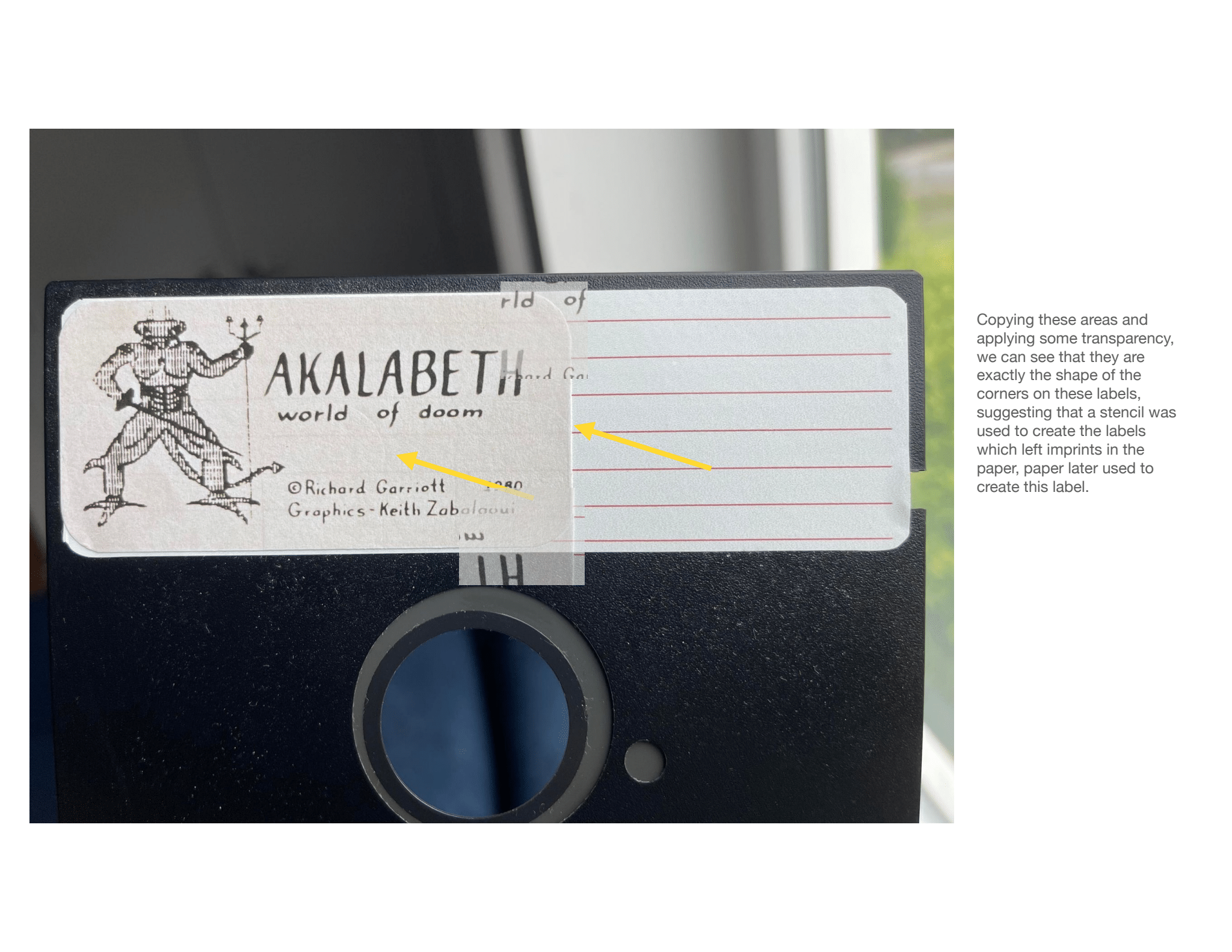

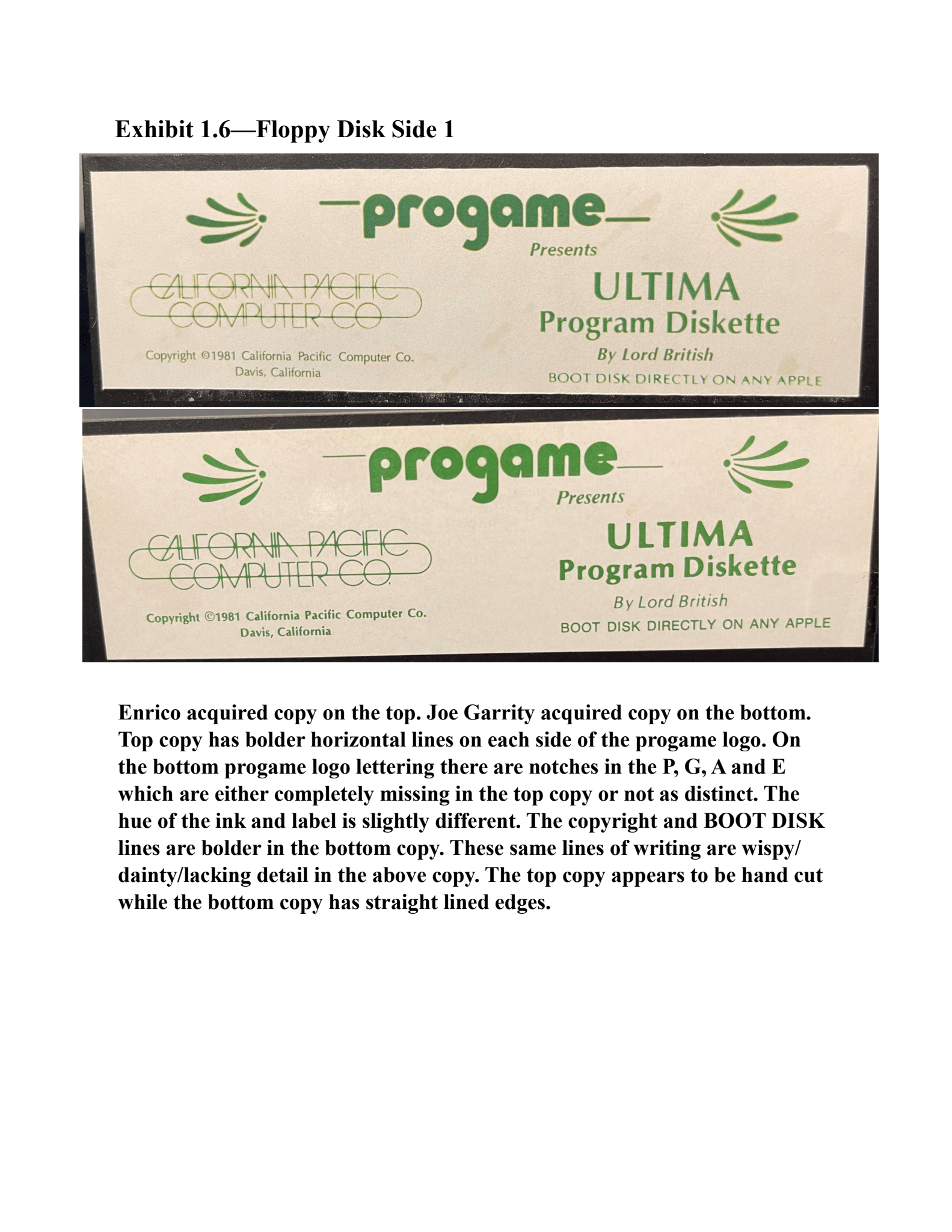

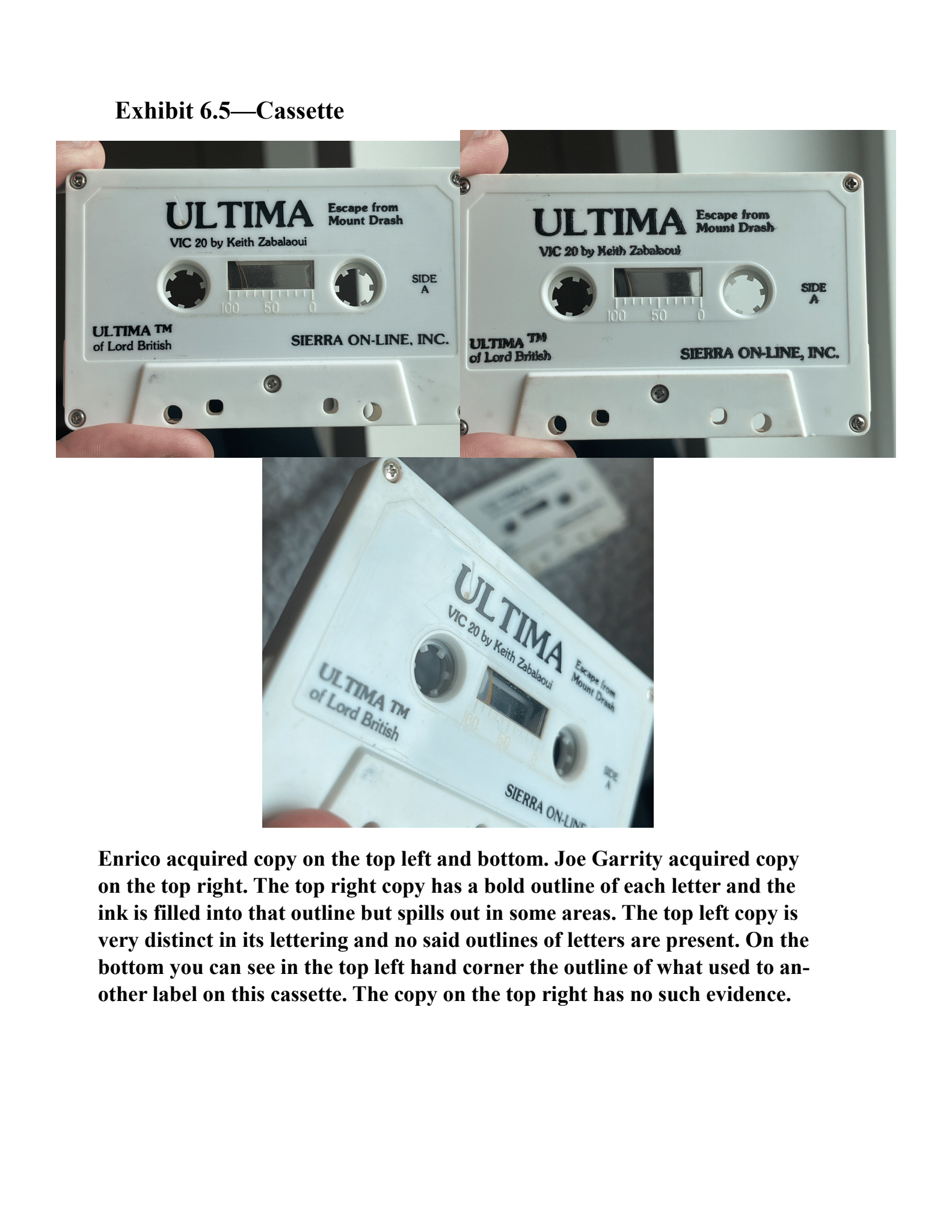

- MEDIA: Disks were tested, and many did not include game data. Disk labels appear to be hand-cut, different sizes, and printed on modern technology. Cassette tapes did not have game data on them, had actual audio, or had data patterns that weren't what they should be. Cassettes often had glue residue from the removal of old labels. Some disk labels had indents from a corner template which looks a lot like someone was tracing the rounded corners on top of the labels.

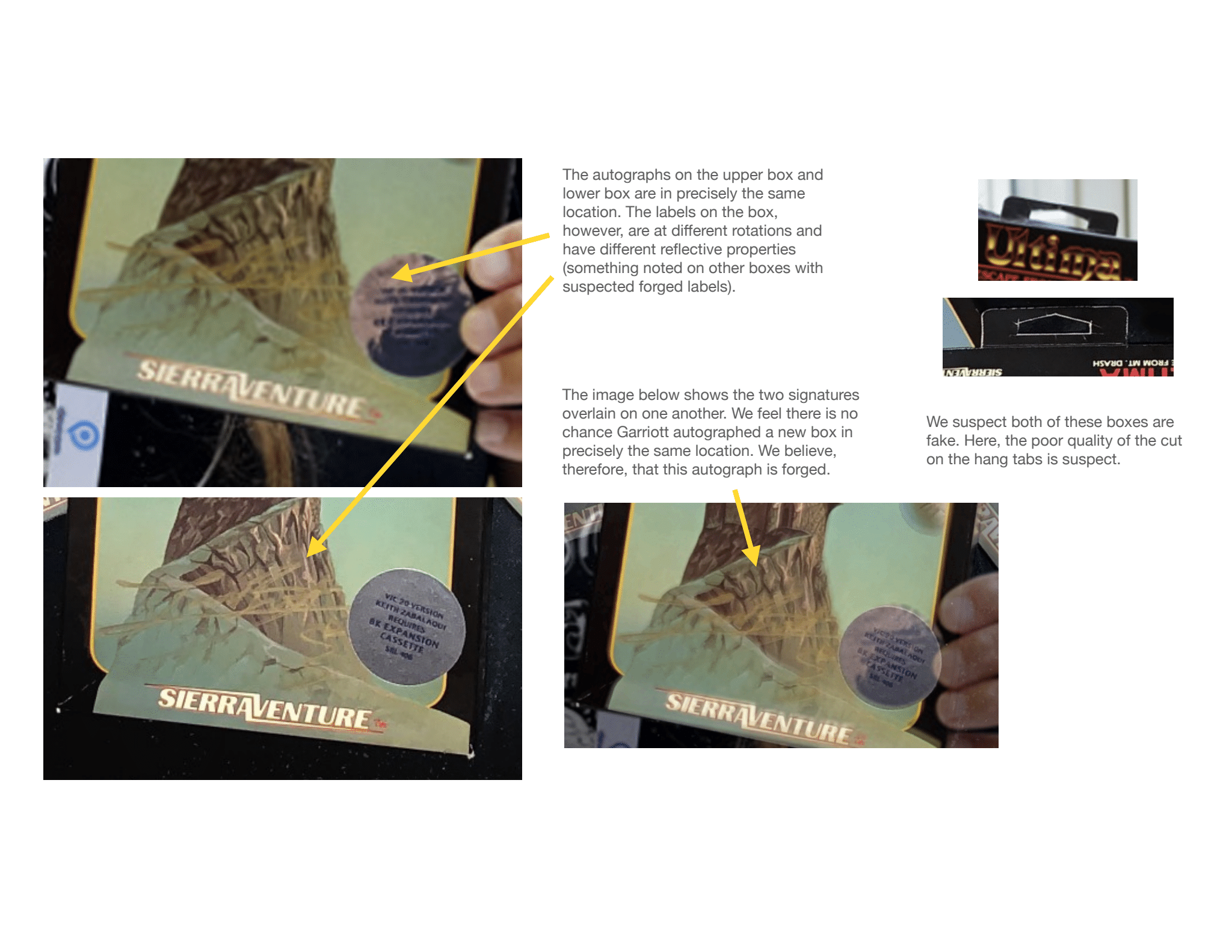

- PACKAGING: Packaging often had all four corners bent in consistent ways. Hang-tab holes appear to be hand cut. Stickers look like they were hand cut or are not exactly round. Packaging is often scratched in a way that appears to be consistent with using something to rough it up. Boxes that were supposed to be sealed had the hang-tabs inserted into the slot. Boxes that were sealed with glue had no evidence of glue. Boxes appear to have hand punched holes that would have normally been done with a machine (I don't know what to call these really). Specific security features on games were not present, or were simulated incorrectly.

It also shared an array of visual evidence of the suspected counterfeits, comparing them with known legitimate copies and illustrating the different ways it examined the suspected forgeries. A handful of examples taken from the archive:

Speaking to PC Gamer, Ricciardi denied knowingly selling forged copies of rare games to anyone. He said he's been collecting since the late 1990s, when rare games could still be had relatively cheaply, and while he's amassed a significant collection of his own, has only sold a very small number of them. All the games he's sold that are alleged to be counterfeit were acquired and passed on from other collectors, he added, although he no longer has their contact information.

"I never shipped any games knowing they were fakes," Ricciardi said.

Ricciardi acknowledged that he asked his buyers to keep their transactions secret, but said he did so because he was selling below market prices in order to help other collectors build up their libraries, and didn't want to cause a fuss.

"Many resellers asked for those items and I refused to sell to them, knowing they would have used them for earning money," Riccardi said. "And I didnt want them to know I had sold them at a lower price."

A Big Box PC Game Collectors rep said that the group's "first consideration" when the forgeries emerged was that Ricciardi was not directly involved, but that it ultimately could not accept his claims based on the evidence.

"Ricciardi notes that he merely passed on what he received to others, seemingly without inspection. We find this exceedingly unlikely," the rep said. "During negotiations for these products—most of which were in the $1,000+ range—pictures were exchanged, details discussed and notes were shared showing the product in question.

"In virtually all discussions, details of the condition of the materials were noted and photos exchanged. Buyers were assured that these were authentic pieces, and further shown photographic proof of the item in question—the one being sold—to assure them why this was the case."

The rep also alleged that Ricciardi had sent messages to multiple people claiming to have detailed records on the origins of the games he sold, establishing their provenance, and added that group administrators have evidence of much more recent transactions. One member of the group, for instance, reportedly received suspected forgeries of two games from Ricciardi just two weeks ago.

"All of the cases we have investigated happened within the last five years, the most recent being two weeks ago," the rep said. "There are over 20 items in just the initial investigation of three people, not counting those that we have learned about since. That total is quickly growing."

It's not yet clear whether legal action will be taken over the alleged forgeries: The Big Box PC Game Collectors group said that individual members are determining their next steps forward and don't want to comment any further. The group also released a new guide on how to avoid being scammed by unscrupulous sellers, and disavowed any official connection with Ricciardo, who has been removed from the group.

"Enrico acted as a private entity and just happened to be a member/moderator," an administrator said. "Big Box PC Game Collectors does not take any responsibility for transactions between members. We don't facilitate anything like that. We're just a forum for conversations."

Ominously, the group also suggested in its Facebook statement that the investigation could grow to reveal that the damage caused by these forgeries is even more widespread than currently known: "There have been others coming forward who have been investigating this same thing, but since we're dealing with an amount of alleged fraud that will likely involve police and litigation, they have asked to be kept confidential at this time. Their evidence substantiates our own."

Collectors who suspect they may have received counterfeit copies of games are invited to reach out to any administrator of the Big Box PC Game Collectors group on Facebook, or through email at bigboxpcgamecollectors@gmail.com.

Andy has been gaming on PCs from the very beginning, starting as a youngster with text adventures and primitive action games on a cassette-based TRS80. From there he graduated to the glory days of Sierra Online adventures and Microprose sims, ran a local BBS, learned how to build PCs, and developed a longstanding love of RPGs, immersive sims, and shooters. He began writing videogame news in 2007 for The Escapist and somehow managed to avoid getting fired until 2014, when he joined the storied ranks of PC Gamer. He covers all aspects of the industry, from new game announcements and patch notes to legal disputes, Twitch beefs, esports, and Henry Cavill. Lots of Henry Cavill.