Tyranny has a brilliant answer to broken morality meters in RPGs

Forget good or evil, Tyranny's 50 shades of grey gives player choices room to breathe.

RPGs have, for some time, been enslaved by the idea that every decision should be filtered through a lens of good or evil. Who are you, what are your deeds, and how do others view you? Many RPGs grant access to different quests or abilities depending on your morality rating. But Tyranny's reputation system dares to be different, and in the process it creates space for characters that don't need to fit into arbitrary definitions of good or bad. Tyranny's moral relativity proves why the whole system is pointless, and why RPGs should aspire to do better.

In Tyranny, you're the Fatebinder, an agent of a totalitarian empire that's wrapping up a global conquest. Your mission is to bring Kyros' law to her new subjects, but how you interpret and execute that law is up to you. Obsidian Entertainment has made no secret that Tyranny is about what happens after evil has won that pitched battle against good. But slogans like "sometimes evil wins" are misleading because, ultimately, Tyranny isn't really about evil. Sure, Kyros' secret weapon is magical Edicts that can turn entire cities to rubble. But then again, I live next to a popular country that at one time reduced two Japanese cities to nuclear craters. Like in real life, nothing in Tyranny is black or white.

Tyranny has some powerful worldbuilding but is let down by a few flaws. Read our review to see what we think.

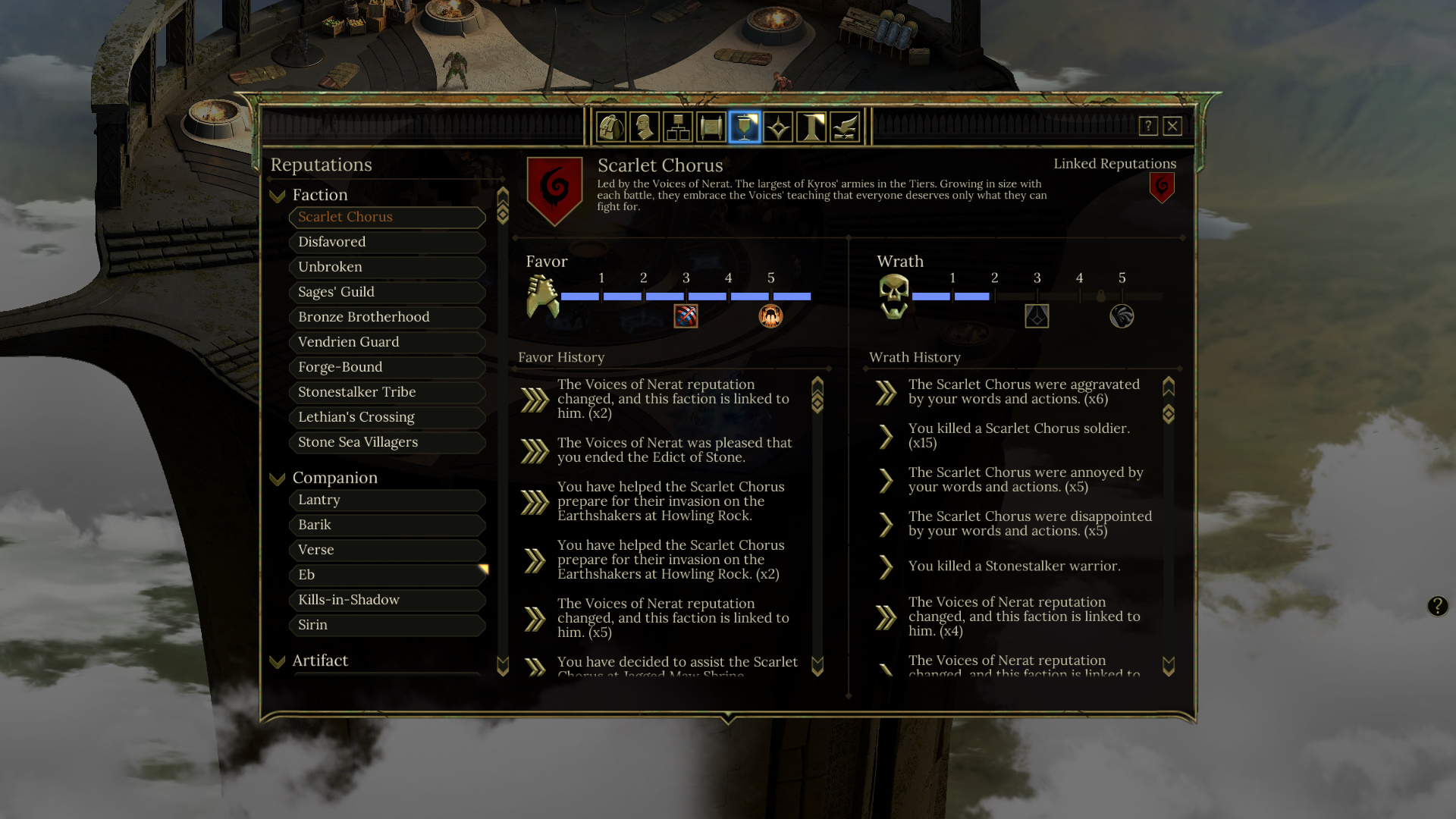

That theme is explored in a complex reputation system that puts your basic morality meter to shame. Instead of judging whether an action is universally good or bad, each major character and faction will filter it according to their principles. Those actions aren't mapped on a single spectrum, but influence two separate meters. For factions, their opinion of you is summarized by favor and wrath. Companions see you through the lens of loyalty and fear. There's no tug-of-war between the two, as each are independent of the other, which allows for very complex relationships. Barik, for example, is so loyal to me I'm convinced he'd fall on his sword if I told him to, but he's also terrified of me—probably because I'd consider asking him to fall on his sword. Relationships like these show how firm a grasp Tyranny has on the nuances that can exist in personal relationships.

By avoiding an all-encompassing morality system, Tyranny itself avoids judging my decisions. When I chose to sacrifice a vulnerable character for the good of thousands, a popup didn't alert me that I had gained 25 evil points. It's up to me to wrestle with whether or not that was the right thing to do.

When you compare that to RPGs like Mass Effect, you begin to see how limiting the conventional morality systems can be. By designing choices that are definitively good or bad (or in this case paragon or renegade) BioWare's system quantitatively measures your character's morality in the eyes of 'god'—the game itself. In Tyranny, it's measured relative to your relationships. During one of the biggest decisions in Mass Effect, you have to decide whether to save the Citadel Council or sacrifice them to focus on repelling a Reaper assault—already you can tell which option is considered good and bad. I don't think it's exactly fair to be considered a renegade because I chose to focus on an imminent threat to the entire galaxy first.

Law of the land

My problem with a universal set of morals in an RPG is the way it makes my character feel inconsistent. Take Fallout 3 for example, where Bethesda haphazardly defines what's wrong and right in a lawless wasteland. It's perfectly fine for me to saw a woman's head off with a kitchen knife—but only because Fallout has made a moral judgment on her: she's a bandit. But if I so much as take an ashtray off of someone's coffee table when they're not looking, I'm a bad person. It doesn't matter how I, my companions, or anyone else feels. Fallout says it's bad, so it's bad.

Morals aren't absolute truths, they're a reflection of the societies and cultures we belong to.

Because these systems tend to assign points to each decision, it also reduces morality to a basic grade scale with some hilarious and reductive results. I can farm up all the positive karma I want in Fallout 3 and then walk into Megaton and crush a resident's skull with a baseball bat.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"I know he crushed Jerry's head like a watermelon and drank his blood in front of the kids," they'd say, "But I dunno, he did give that homeless man some clean water a few times."

Morality doesn't work like that, and good decisions don't negate our bad ones. Reducing every decision to 'angel points' or 'devil points' ultimately weakens the writing of RPGs because it removes extrinsic rewards and ambiguity. It discourages players from interpreting for themselves whether something was bad, good, just, immoral, or something in between. While Tyranny's reputation system does grant reputation-specific abilities, they don't feel like carrots on a stick meant to entice you one way or the other. No matter what decisions you make, you'll earn extra abilities depending on how factions and characters feel about you.

Roleplaying games, more than any other genre, aspire to create believable characters and situations I feel invested in—but they undermine that ambition by slapping a big tacky meter that simplifies who my character is. Morals aren't absolute truths, they're a reflection of the societies and cultures we belong to. The more games start creating systems that better understand this or—better yet—ignore the idea of a moral compass altogether, the more thoughtfully we can explore choice and consequence.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.