Our Verdict

Not a dramatic reinvention, but still an enjoyable game of construction, economics and election fraud.

PC Gamer's got your back

I am not the man you want running your country. Over the course of my extended presidency I've smuggled rum into a prohibition America, sided with Axis powers during both World Wars, systematically stripped away the liberty of my citizens, and assassinated a grandma for opposing my regime. I'm not proud of these things, but I'm glad that I felt the need to do them. For all Tropico 5 adds to the city-building series—and all the ways it doesn't advance the formula enough—its greatest success is in pushing you towards the murkier aspects of dictatorial rule.

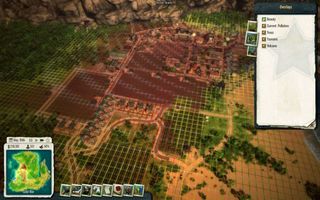

Rather than inhabit the genre's favoured role as the floating god-mayor of urban planning, in Tropico 5 you play as a banana republic's ruling dynasty. You still use a top-down view to place buildings and trade goods, but must also navigate the island's politics—surviving both the international machinations of world superpowers, and your populace's desire for democracy and happiness.

Where Haemimont's previous two Tropico games took place around the Cold War, this time the action spans across multiple eras. It changes the pace and shape of a sandbox campaign, offering a longer period of island management that encourages a broader range of industry and development. More importantly, it restricts your early-game options, making for a harder fought battle to stay in power.

After declaring independence from the crown in the Colonial Era, my people asked for elections. Foolishly, I agreed, having been conditioned by previous games to expect an easy win. Only, without access to the advanced industry that would normally bulk up my war chest, I wasn't able to effectively address the needs of the populace. Instead of securing power through the creation of a paradise, I did it via the more realistic tools of intimidation and election fraud.

Throughout your rule, optional objectives appear over your palace, offering bonuses for filling desired criteria. Usually it's in the form of constructing specific buildings to appease one of the political factions, but occasionally something more interesting and wide-ranging appears. My brief bootlegging period was a direct result of one of these missions, and its promised reward of more favourable trade prices. The downside was twofold: my island became a haven for crime lords, and America became very angry. Luckily, when a country invades you, they never pose a serious threat; instead choosing to stomp around like angry toddlers, destroying bits of the city.

The missions help to add a dynamic element to the sandbox mode, but their limitations are clear. Instead of reacting to the specific choices you've made, they're pulled seemingly at random from a pool of possibilities. Throughout I was offered objectives that I'd already fulfilled, and instantly credited with success upon accepting them. Better implemented are the requests that come from agreeing to negotiate with protesters, which are, at least, offered in direct response to your island's failings.

More significant are the potential rewards these missions offer. That's because, unlike in previous games, your Swiss bank account finally has a purpose. This time there's a persistent element to proceedings—your dynasty expanding across every game, be it sandbox, multiplayer or campaign scenario. You can switch between family members each election, and they all offer a different global bonus. It's these bonuses that can be upgraded with embezzled funds. Now when a faction offers you a choice between extra trade routes, additional finance or your own private bank account, it feels like a more meaningful decision.

For all its improvements, Tropico 5 is still iterating on the template set by its predecessors. In many ways, that's a good thing—it's a formula that, behind the overt political caricatures, is deceptively clever. The key is in the way it simulates every citizen, letting you select, follow and harass them individually. The scale is well measured, too. Islands don't feel small, but their population is low enough that there's no abstraction of data. That has a dramatic effect on how you construct your cities, because the way you identify problems feels natural. An icon may tell you that a factory isn't receiving its required raw materials, but you can manually track the production and transportation of those goods to identify and address the bottleneck.

The problem is that, with every successive release, Haemimont are essentially making a more refined version of Tropico 3. Even when spread across a longer timeline, Tropico 5 fails to meaningfully move the series forward. It still has the same cheerful vibrance, the same salsa-infused soundtrack, and the same selection of infrastructure, industry and tourism.

If you're new to Tropico, don't be put off: this is the version deserving of your vote. But as a returning ruler, I was hoping for more of a revolution.

Not a dramatic reinvention, but still an enjoyable game of construction, economics and election fraud.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.

Cut the cord on your PC gaming setup this Presidents' Day with an excellent wireless Logitech keyboard and mouse combo for almost 50% off the list price

Japanese patent attorney, burdened with a party pooper's knowledge, says Nintendo having 22 out of 23 Palworld-targeting claims 'rejected' in the US is business as usual

The new game from The Witcher 3's director revives the best tradition of Morrowind by letting you kill off 'really important NPCs'