Our Verdict

The pixel-art is faultless and the gameplay is pleasingly reminiscent of the classics, but Timespinner doesn't offer much that feels new.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A Castlevania-aping modern platformer.

Expect to pay $20

Developer Lunar Ray Games

Publisher Chucklefish

Reviewed on Core i7-4720HQ, 16 GB RAM, GeForce GTX 980M

Multiplayer None

Link Official Site

The pixel dam is bursting. This year has seen the arrival of many an anticipated retro-styled platformer, with the likes of Chasm, Death’s Gambit and Iconoclasts emerging from long development periods into the hands of salivating fans. Timespinner hit Kickstarter four years ago, exceeded its $50,000 goal threefold, and promised roughly the same thing as a lots of its contemporaries: lushly animated pixel-art graphics and ye olde 2D platforming.

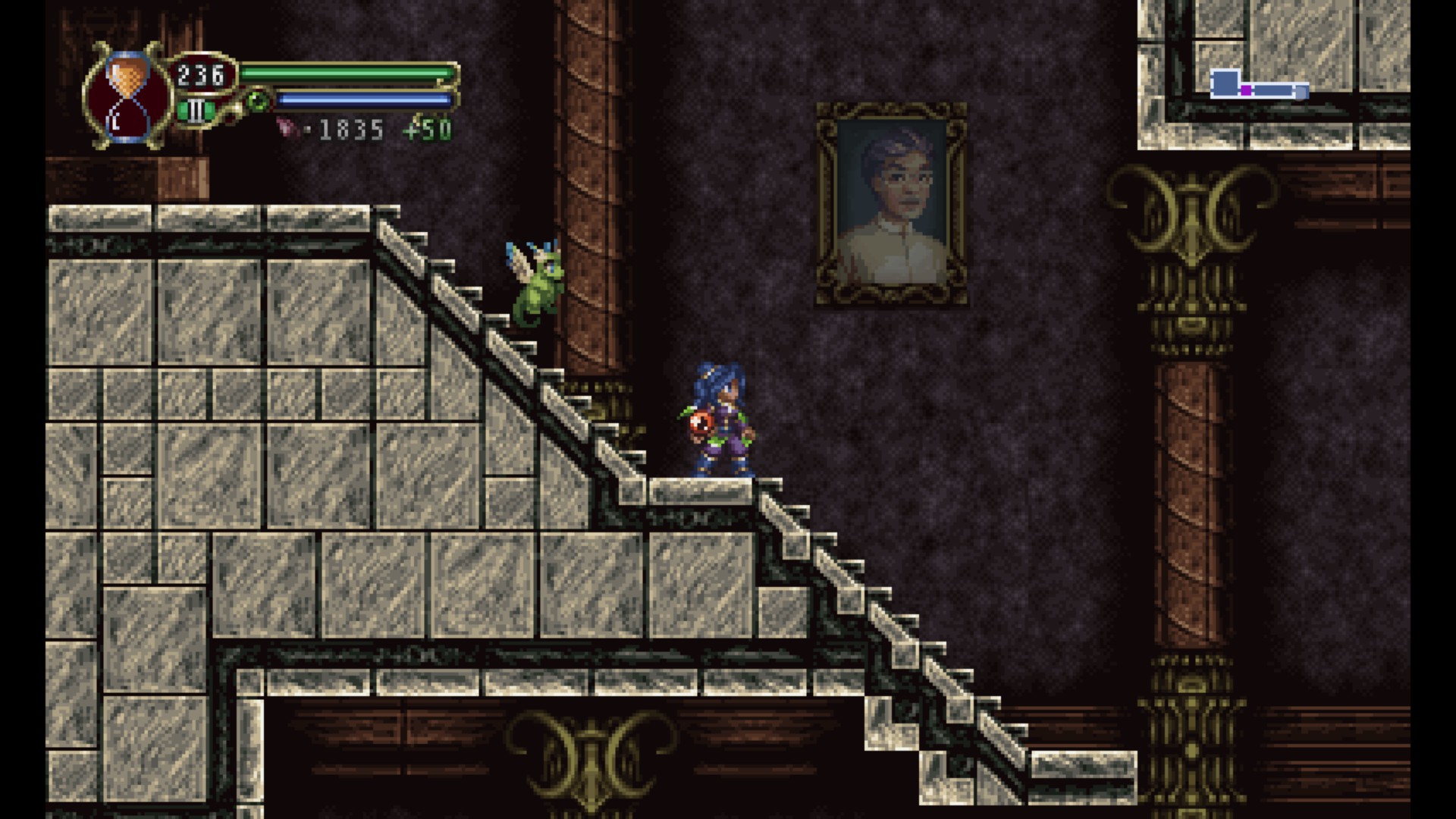

In 2018, however, it’s really hard to stand out in this genre. Timespinner is a Metroidvania and Metroidvanias are now ubiquitous. Plus, they all have Hollow Knight to live up to. Timespinner does benefit somewhat from being conservative: the resemblances to the classic Castlevania: Symphony of the Night will be immediately obvious to anyone who’s played the latter.

The story follows Lunais, a ‘Time Messenger’ tasked with travelling back in time to warn her descendants of oncoming strife. The Lechiem Empire is the big looming threat, and by sacrificing her very existence, Lunais needs to travel back in time to ensure they’re never a threat to begin with. Despite that heavy-sounding subject matter, the story is suffused with a light melancholy: Time Messengers can’t return to the present once they’ve used the nominal Timespinner to travel back in time, so her journey is one tinged with nostalgia and fuelled by sacrifice. That’s exacerbated by the fact that Lunais’ mother was murdered right before she took the plunge.

Timespinner’s core conceit is Lunais’ ability to pause time. This is useful in combat: while she’s got a backdash ability, pausing time is a more effective evasive maneuver. The pause is toggled with a button press and powered by sand, which is easily discoverable throughout the world. Pausing time can also turn enemies into traversable statues, so that with precise timing, you can use them to reach otherwise inaccessible areas. You can even climb the poison butterflies.

After a few hours of play, the light RPG aspects of Timespinner emerge. These revolve around Lunais’ Aura power, which manifests through the use of orbs. Regular attacks vary between swords, fireballs, ice-blasts and more. Special attacks, which dole out more damage, use up Lunais’ Aura meter. Lunais can equip two offensive orbs at once, meaning the primary attack can cycle between a sword and a close-range fireball, to mention just one early example. These orbs level up with use, and it’s fun to experiment with different combinations. I’d have liked for these dual-wielded orbs to interact in interesting ways, but since they can be modified on the fly, you’re never lacking the freedom to deal the type of damage you want to, and enemies do eventually have elemental weaknesses.

Lunais also levels up, which improves her damage output, and loot is randomised and always fun to retrieve: there are enough number-fuelled items in the game to make each newly-opened chest feel potentially empowering. Items can be modified and buffed as well, though it doesn’t feel necessary to dabble in any crafting. And of course, Lunais gradually adopts various powers that enable her to access previously out-of-reach areas.

These aspects provide the usual carrot-on-the-stick momentum to what is ultimately a very conservative game. The pixel-art is gorgeous, but the environments are same-ish and drab at times: some areas are just interminable hallways of enemies, and while the outdoor environments are stunning and evocative, the same can’t be said for most of the interiors. Remove the ingrained appeal of pixel-art—especially to a certain generation of player—and the world design of Timespinner wanes in its attraction, especially when games like Owl Boy and Iconoclasts dazzle with their ever-varying level themes. As for sheer ingenuity of interconnected level design, Timespinner can feel rote compared to the vast and ever-overlapped majesty of Hollow Knight. The room layouts are often repetitive, so that unlocking a shortcut registers as a convenience rather than a gamechanger. I never marvelled at the lay of the land in Timespinner, I was never prickled by a new understanding of its interconnectedness.

Nostalgia is a powerful sentiment, and Timespinner’s theme of destroying a character's investment in the present in order to go back in time to fix things does resonate well with its '90s-rooted aesthetic. But for those with no connection with the era Timespinner apes, there’s not much here to love. I enjoyed it, but it was a mild and affectionate enjoyment, a pleasure born of its lavish art style and my familiarity with its beats. It’s expertly crafted, with a thorough understanding of what makes a game of this mold tick. But increasingly, that feels insufficient in a field so increasingly bloated with gems.

The pixel-art is faultless and the gameplay is pleasingly reminiscent of the classics, but Timespinner doesn't offer much that feels new.

Shaun Prescott is the Australian editor of PC Gamer. With over ten years experience covering the games industry, his work has appeared on GamesRadar+, TechRadar, The Guardian, PLAY Magazine, the Sydney Morning Herald, and more. Specific interests include indie games, obscure Metroidvanias, speedrunning, experimental games and FPSs. He thinks Lulu by Metallica and Lou Reed is an all-time classic that will receive its due critical reappraisal one day.