Three bizarre sci-fi tales from Torment: Tides of Numenera

In our hands-on with a new section of Torment, we encounter wet mouth portals, mutant orb friends, and a deadly jar of wind.

My time with Torment didn't reveal anything new about how Torment plays, but Chris Thursten went into it in-depth a few months back. Check out that preview for lowdown on combat, stat progression, Planescape's influence, and the Numenera roleplaying world.

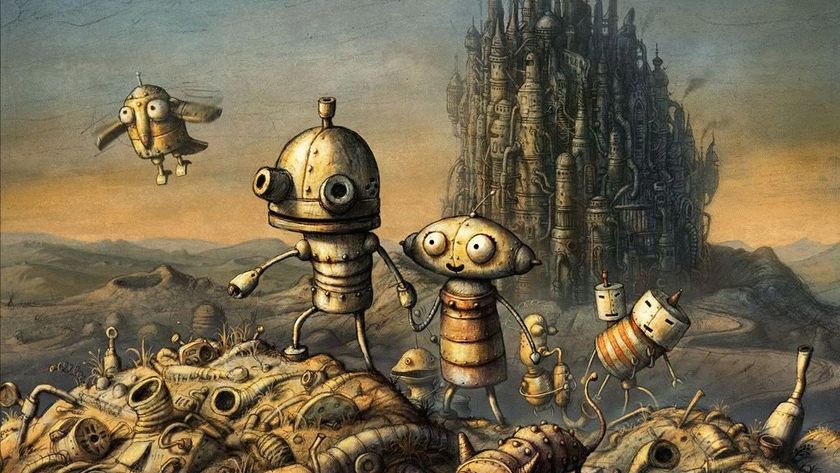

I wonder if this massive interdimensional tentacle monster-city can feel my feet on its, um, parts, and if it tickles or stings or if the trampling of so many human and mutant and whatever other forlorn lifeforms’ feet have made The Bloom bruised and numb by now.

In Torment: Tides of Numenera, the spiritual CRPG successor to Planescape: Torment, it doesn’t take long for my surprise to morph into hunger. I have my arms wide open, ready for whatever the hell the Numenera roleplaying universe allows, which is apparently just about anything.

Based on two hours from a preview event after being plopped into the middle of the story, I was disoriented and without a stake in the overarching plot and characters, but more absorbed in it than any game narrative in recent memory. So in place of breaking down the combat systems of a game you can already play in Early Access, here are a few snippets of story and moral strain from my short session.

A very large and important and wet mouth

Torment is a buckwild anthology of anything-goes sci-fi and fantasy storytelling. You’re the Last Castoff, who is basically a wandering wizard’s dirty sock, a consciousness born into the old body of a “changing god.” They change often, I suppose. You’re being chased by a bounty hunter demigod called The Sorrow, and by escaping through a portal, the Last Castoff ends up in The Bloom. Take a breath, it’s going to be OK.

Over time—however time passes when you’re suspended between dimensions—The Bloom became home to a genuine city, replete with a market, ghettos, and a problematic civic governance. It’s basically America, except with a moist ambiance and tentacles are as commonplace as coffee shops. Just as I take the train to work every morning, the residents of The Bloom pop back and forth in time and space via gaping maws. They’re literally big, wet squid mouths that pop up wherever The Bloom chooses.

Instead of a metrocard, they require a more substantial offering to open up. Each maw feeds on specific kinds of people. It won’t necessarily eat them whole—it can and just might—but a treasured memory, the ability to feel pain, or even just a finger are all up for grabs. It’s impossible to know until its slimy tendrils close down on you. I’ll have to use one to escape, but it won’t be easy.

You’re meant to make friends and feed them to a moist hole.

I head north and into the remnants of a crashed ship. The ship AI lights up and asks me who I am and why I’m there. With a bit of charm, I calm the AI and listen to its story. Advanced enough to feel guilt, the ship AI felt responsible for killing its crew, so it replicated them digitally as a means of tricking them or whatever was left of their collective consciousness, into eternal life. After some skill-check persuasions, I convince the ship AI to let me take the AI replications of its doomed crew with me. I’ll find them a more reliable source of power, sure. I download them, assimilate them into my cyberpunk brain fittings, and the ship AI shuts down for good. I feel clever and terrible all at once.

Earlier, I rescued a psychic from slavery and she tipped me off that one of the maws was hungry for guilt. Fry some up in coconut oil, a bit of rosemary—delicious. With the ship AI’s embodiment of guilt embedded in my mind, I offer myself to the maw. It sniffs out the data (along with a bit of HP) and teleports me to a space station orbiting a planet somewhere and somewhen far, far away.

Within five minutes, a quest invoked the ethics of murder and what constitutes life. The Bloom is jam packed with these micro morality plays, ripping through them before your conscience has time to react. It might be one of the most intriguing and insidious zones I’ve played in an RPG. In order to find the right person to open a maw, you need to practice empathy, examining the habits and personalities of every character you encounter. But they’re all just a means to an end, a quick snack for the maw and your ticket out of there. You’re meant to make friends and feed them to a moist hole. I'm happy to do it though, especially for my new mutant orb friend.

Mutant orb friendship tips

Little Nihliesh is a ghetto in The Bloom where the forlorn members of a mutant species have made a ramshackle imitation of their home planet. They’re a misunderstood bunch, stepped on and exploited often by the residing Bloom military forces, and it’s during one such scuffle that I befriend both sides.

Two groups, one of mutants and the other of Bloom soldiers, stand across from one another and shout accusations. They’re about to fight, and it wasn’t “Crisis Initiated” in fanciful letters splashing onto the screen that tipped me off.

It plays out like a typical RPG battle with each unit, including my own, taking turns to move and act. But unlike the latest bunch of CRPGS (Tyranny, Pillars of Eternity, Wasteland 2), I have the option to talk instead of stab. With every turn, I divide my party and practice diplomacy. After asking some questions (and bribing the mutants with money), I’m able to talk down both parties and carry on through Little Nihilesh. It’s there I meet the leader of the local mutants, a prince in exile stuck inside a giant metallic orb.

Gar-Koto and I become buddies, of sorts. He's curious to know what I saw beyond the maw, and I tell him it wasn't his home planet. Continued exile isn't the worst that could happen, he reasons, and Koto is far more pleased that I discouraged his people from violence and shed light on their humanity in the presence of the Bloom soldiers than anything. Koto takes a shine to me. The feeling is mutual. He may be the implication of a living thing, floating around somewhere in that sphere, but shapes need love too. Finally, an RPG that doesn't force you to punch or stab to connect.

A jail bust and deadly gust

After our painful goodbyes, I start the search for the standard of a downtrodden platoon I met earlier. The Murdens, a disheveled race of bird humanoids stole it from them. They’ve made a home in the tunnels of The Bloom, where they’ve been known to hoard stolen nicknacks for some time now. Besides their reputation for thievery, they’re also known for a general distrust of humans. Convenient. I’ll probably have to fight them, because subterranean dungeons need bad guys to bag, right?

In Torment, not so much. I use some charm and a lucky skill check to talk them down. With free reign, I wander their tunnels, peeking in on prisoners and offering myself to a tiny, mobile maw who teleports me to the Murden treasure room. I take everything, of course.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

As I try to make my getaway, I notice a cell I’d blown by earlier. The door is unlocked so I wander in and chat with the prisoner. Her name is Skoura the Faceless, and she won’t quit going on about this damn jar. It’s full of Iron Wind, a powerful reality-shaping nanite. I don’t know this, because I don’t pay attention, exactly. The Murdens are on my ass (and my demo time is running out). Skoura warns me against opening it, which is good advice, but given the offer to open anything someone doesn’t think I should open, I have to, you know? It’ll probably make me powerful, or I can flip it up top for cash later. So I open it and the nanites consume me. I’m dead.

The developers running the event were surprised I found one of the few ways you can perish outside of combat in the preview build. It’s very on brand for me to do the very dangerous and stupid thing in spite of a flood of warnings. They reassure me though, saying death is sometimes the best option in Torment, and not necessarily the end. Good. The more a roleplaying game doesn’t feel built around shunting the hero through the typical journey, the better. I want the option to play a weak, fickle coward or a brash, foolish grunt and Tides of Numenera might just let me.

I don’t know what such choices will mean in the long term, and I’m not sure I actually care. The writing is clear and outlandish enough to feel natural to the blank slate character of the Last Castoff, giving emotional texture to a fictional universe without a bottom. Whether the overarching narrative builds and releases in a satisfying way remains to be seen, but as a dense series of disgusting, surreal, and morally twisted short stories that I can play as the hero or a nobody, Torment is trending towards excellent.

James is stuck in an endless loop, playing the Dark Souls games on repeat until Elden Ring and Silksong set him free. He's a truffle pig for indie horror and weird FPS games too, seeking out games that actively hurt to play. Otherwise he's wandering Austin, identifying mushrooms and doodling grackles.