The writing in FTL

In Why I Love, PC Gamer writers pick an aspect of PC gaming that they love and write about why it's brilliant. Today, Sam admires the skill of FTL's quest writers.

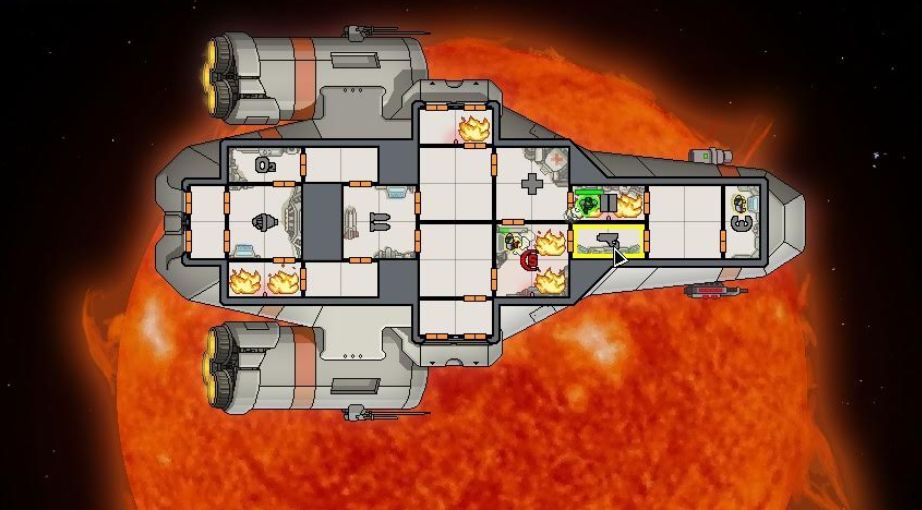

Right now I’ve got an absolute ton of the best games downloaded to my PC, but I’m still only playing one that I’ve played to death many times before. FTL: Faster Than Light is now almost three years old, but thanks to the Advanced Edition released in 2014, it’s fair to say it now feels complete. There’s enough in the way of strategies and variables for years and years of play—which, apparently, is what I’m going to do, even though Invisible, Inc and The Witcher 3 are ready to go on my PC.

I admire a lot about FTL. It feels oddly targeted towards whatever type of player I am: I love fiction that involves spaceships, I enjoy real-time strategy and I like story as much as anything else in a game if it’s done well.

There are different ways that writing is used in games. Cutscenes or dialogue boxes are the most obvious examples, and yeah, often it’s total rubbish. I’d never really thought about how less could be more in games writing until I played FTL. It’s concise but detailed, sometimes serious sci-fi but with a sense of humour. The writing in FTL is, I think, perfect.

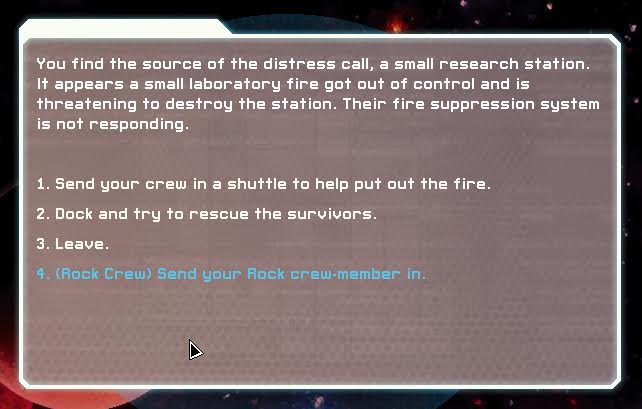

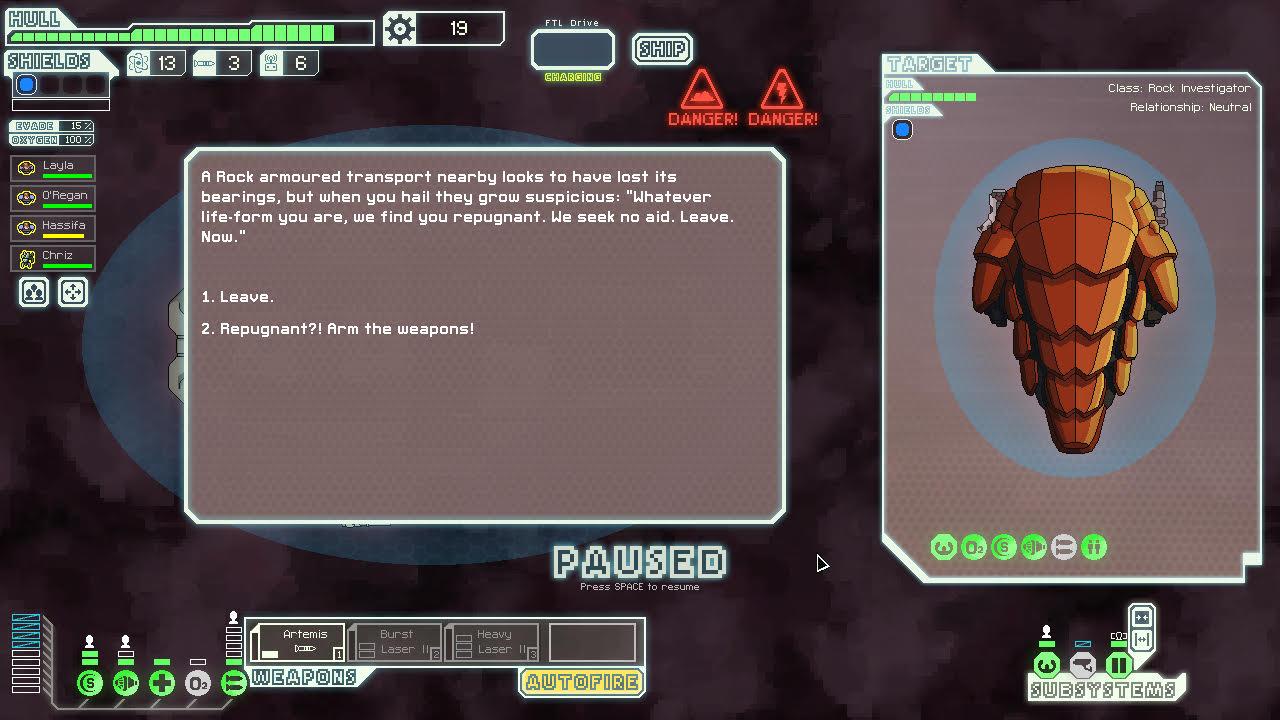

FTL tells the story of its universe in one or two paragraph chunks. Every time you jump, you receive a new bit of flavour text—whether it’s a slaver selling his wares, someone bribing you to turn the other way and dozens of other possibilities. The same ones recur but there are some instances that you see less often. For example, I can’t recall being able to attack an alien spaceship for calling me ‘repugnant’ more than about three times in maybe 50 or 60 playthroughs, and last week I encountered one about a tourist trap in space that I don’t think I’d ever seen before.

I’ve encountered the same bits of text over and over again by now, but it’s still appealing to see the order in which they connect together or play out. A common scenario is finding a crew member who’s the last of his kind—”You find a colony that seems to have been recently attacked. Exploring the devastation, you find a lone survivor.” When I meet this guy on my journeys now, I always invite him on the ship, even though there’s a good chance he might end up blowing himself up or killing a crew member.

You’re just rolling a dice, really. There’s no animation to suggest that he went mad in the medbay and stabbed Captain Samuel Roberts in the face, for example—but the writing gives you enough incentive to fill in those gaps yourself. I think you really have to lack imagination to envision FTL as a series of stats and not see it as your personal series of Battlestar Galactica.

I think writer Tom Jubert made a significant contribution to FTL’s success. Take the writing and story away and you still have very competent real-time space strategy game, where the framework is more obviously about rolling the dice with enemy and resource outcomes as you jump from system to system. But it would lose a significant amount of its magic. This text is as important as the art in making FTL’s fictional universe feel like its own thing, in the same way a throwaway line about the Clone Wars in Star Wars hints at a mythos beyond what you’re seeing on the screen. It’s very well-judged in its brevity, and is one of the best examples of writing being used well in games that I can think of.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.