The Wages of Sin

Every week, Richard Cobbett writes about the world of story and writing in games.

Everyone loves a good villain. Actors adore playing them, to twirl a moustache and dine on scenery. Movies like Day of the Jackal are intriguing looks into their worlds, that can build sympathy for the raw effort even if the goal is morally wrong. There's few character archetypes as immediately compelling as the Magnificent Bastard, who sees the invisible strings of the world and makes it dance to his tune.

Except in games. Very, very few games have offered anything close to that, and those that have got closest either hide behind a shield of chaos (Saints Row, Postal 2, though believe me, those games are NOT on the same level) or play it off as tragedy (Spec Ops: The Line, Traffic Department 2192). Rarely do they dare to take anything but the Grand Theft Auto or Dungeon Keeper or Varicella (there's your obscure shout-out of the week) approach, where the main character is evil fighting against a bigger evil. Dungeon Keeper had the map and nominal heroes, but really the focus was on fighting other Dungeon Keepers. A later game with a similar vibe, Overlord, had you as an up and coming demonic presence fighting the forces of good, yes, but the forces of good who had long since been corrupted anyway, before revealing that the actual villain of the game was your predecessor who had been using you as nothing but a pawn.

When they do, it's usually a question of backstory. The protagonist of, say, Amnesia or Planescape Torment, gets to discover all manner of horrific things they did, but since the player isn't actually complicit in it, they don't feel 'real'. Evil can be done by accident, as Spec Ops: The Line repeatedly proves with its lead character Walker's slide from would-be saviour to destroyer of Dubai, but villainy has to be active. It's much the same as heroism not conventionally being seen as doing good deeds in exchange for something, at least in the modern era. (Go back to, say, Greek myths and it's actually nothing else - much of the Iliad for instance rests on Achilles' entirely justified backing out of the fight until he gets what's his, with his later 'crime' not being sulking in his tent, but not accepting the proper compensation when finally offered.)

Now, there are definite cases of villains being villains, even if they're up against bigger ones. Evil Genius for instance is a Bond villain simulator, Legacy of Kain is predicated on the original game's hero becoming a monster, Command and Conquer has never shied away from terrorist factions and very few of Star Wars: The Old Republic's Sith characters are intergalactic teddy-bears. You can definitely find examples. They're oddly rare though, given how initially tempting playing the villain always sounds. Who doesn't want that control? Who wouldn't want the nations of the world bowing before their might and power and hoping for a little crumb of mercy?

But even in the games that try, it rarely turns out as good as it sounds. For several reasons. The first is that for most people, the idea of being bad relies on being distant. It's one thing to torture a Sim or bulldoze a house in SimCity, but the more invested you are in characters, the harder it usually is to hurt them. Crushing spirits, inflicting needless pain, even something as mild as making children cry as you steal their lollipops doesn't feel good because it's not supposed to feel good. That's not villainy, it's dickery. And it can ruin games. I've no moral objection to Grand Theft Auto, but San Andreas routinely made me very uncomfortable, and not in a good way - the mission where you have to drown a music producer because he offended a friend you don't even like almost had me put down the controller. A later one where you bury a guy alive in concrete because his employees whistled at your sister was the end of my time with it. I later finished it on PC, but could never get past how bad it made me feel, despite having loved Vice City and its whimsical missions like selling drugs from an ice-cream truck. Only 'fun crime' is a fun time.

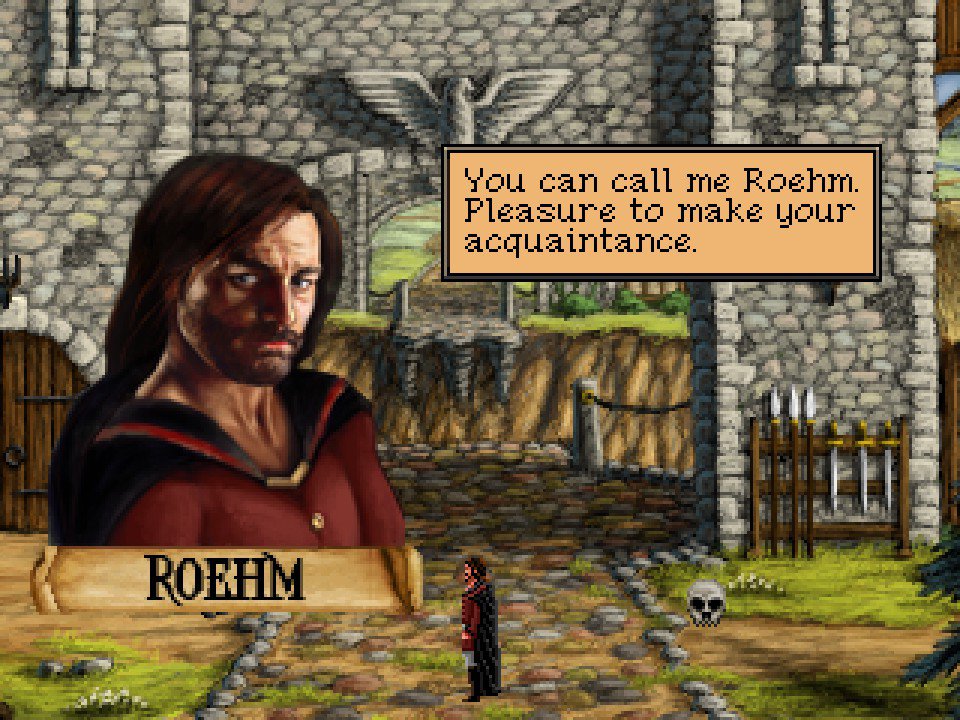

(This often seems to strike developers in mid-flow. Quest for Infamy for instance, which is a really well made take on the Quest for Glory games, was intended as a parody where you were a villain or at least in that ball-park. In practice, you do almost nothing that a hero wouldn't except for snarking at people, and occasionally making comments about things you could do, but then... ah, don't.)

Evil vs. Evil can at least run with this. You're not punching down in the same way, and there's the element of self-righteousness that tends to be core to actual villains. Very few in history have simply done what they did for the lulz, as it were; what makes them scary is that they thought they were right. This may not be the road to hell paved with good intentions, but neither is it one to just merrily skip down. In these situations, the powerful wage their war and simply don't care about the collateral damage as anything other than point-scoring. Or alternatively, play like Dr. Doom. Your own people are precious not because of the sanctity of life or anything like that, but because they're yours, and nobody fucks with your shit.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

More pragmatically though, villainy is a hard path to offer. The standard story structure tends to be that villains act, heroes react. One provides a reason to save the world, the other handles it. Comic books especially have demonstrated that when this is flipped, bad things tend to happen - the greatest heroes quite easily slipping into fascism and abuse of their powers. The catch is that instigating actions is a much harder thing to script, and a less freeform thing to actually play. Heroes can be clever, but they tend in games at least to follow a roughly straight line through the problem, taking each encounter as it comes. Villains meanwhile need plans on top of plans, feints, bluffs, resources and a long term strategy that's far more complicated than 'go beat up the guy with the biggest shoulder pads.'

In games, this means that even when we get a 'villain' option, it's usually firmly in the 'dick' category. It's opportunistic cruelty, it's being mean to people, it's doing the stuff that would make you unpopular in the real world, and so doesn't exactly help in a fantasy one. The occasional burst of it can still be fun, like head butting the reporter in Mass Effect, or abusing your faked position to pass as a Sith in the first Knights of the Old Republic, but few narrative driven games allow for the ability to plan ahead enough to be anything other than that. Strategy games have a big advantage here of course, with Crusader Kings especially offering lots of options to play however you choose. Even then though, your imagination has to fill in many of the details and cover for when the game doesn't entirely get where you're going with things.

What's frustrating is that many developers, especially in RPG, still feel compelled to write villain paths that either make no sense or contribute very little indeed. Often, they're just crazy. The original Bioshock for instance opted to make killing a couple of the Little Sisters into your instant ticket to the bad ending, and while killing little girls for prizes obviously sounds bad, there are plenty of arguments to be made for it. That you're sparing them their horrible lives. That the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few (RIP, Leonard Nimoy). That they're simply zombies, no more people than the less cute splicers that are equally victims of Rapture but nobody gives a shit about. Any sense it makes is then further destroyed by the fact that there's no chance to atone once you find out the truth, which is particularly rich given that your "You are horrible" speech comes from a former concentration camp doctor trying to do exactly that.

But, multiple paths sounds good on boxes, so many have tried to offer them. And I think we all know what that's actually translated to. "Good" is the karmically pure path, where you do good deeds nominally for the sake of doing them but really because you get more spiritual bonuses like XP or better 'nice' magic powers. "Bad" is having the temerity to ask for payment. "Evil" is being so twisted and dark that you actually expect to be paid something vaguely approaching a reasonable amount for having risked your life and probably burned through a ton of supplies in the process. You awful brute.

The result is that most players take the 'good' path by default, both because it's the heroic thing to do, and because it's almost always the most profitable overall. It's not like anyone's going to balance a game's economy so that you're screwed if you don't demand your cash, and it's a rare RPG where money doesn't become utterly irrelevant by around the half-way point. This in turn means that developers have to focus on this, and the 'evil' path gets very little love. There are very rarely many unique quests for players on that side of the line, with the main narrative branch point typically coming right at the end to save time. It ends up being less a choice as the vestigial idea of a choice. Really, unless a game is actually serious about it, like Planescape Torment, it's usually to its detriment to even offer something so out of character.

Despite all this though, it would be good to see some more games that do this well, if only to have a better baseline than we do now. Nobody so much as raises an eyebrow at going to see a movie that glorifies gangsters or con artists or cat-burglars, even if most of them don't get away scot-free, and there's no reason why games should have that very visible frisson of tension and controversy for taking a walk on the wild side, be it something like Payday, or even - playing devil's advocate here - even a Hatred.

It's unlikely though that being evil is going to become more compelling in the near future. It may not eat away at your virtual soul, it may be a fun way to blow off steam now and again, but it's never going to have quite the internal warmth of helping people, making characters you care about happy, and making the world a better place. On a screen or off, empathy is always going to be more satisfying than sociopathy, especially when sprinkled with a few ways of reminding the world that being nice isn't the same as being weak. It is a lesson many villains learn to their cost.