Our Verdict

A tense and spooky stroll through a gorgeous world, some fun supernatural detective work, and an efficient script with sparse dialogue.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A first-person mystery adventure game with supernatural elements

Play it on: Intel Core2 Duo or equivalent AMD, 4GB RAM, DirectX9c compliant card with 512MB of VRAM

Reviewed On: Windows 7, Intel i7 2.8 GhZ, 8GB RAM, Nvidia GeForce 660Ti

Copy protection: Steam

Price: £15/ $20

Release date: Out Now

Publisher: The Astronauts

Developer: The Astronauts

Multiplayer: None

Link: Official site

Paul Prospero's job description, Supernatural Detective, isn't just awesome, it carries a double meaning. Yes, he's an investigator of the supernatural, visiting Red Creek Valley to solve the mystery of a young boy's disappearance and several gruesome murders with supernatural overtones, but he's also got magical powers himself, able to psychically view the past as a series of ghostly images, like a spectral highlight reel. By examining clues, reconstructing crime scenes, and replaying past events, Paul can piece together the events leading up to Ethan Carter's disappearance... when he's not stopping to gawk at one of the loveliest looking games ever made.

"This game is a narrative experience that does not hold your hand." This is the first thing The Vanishing of Ethan Carter tells you. It feels like a bit of a boast, and it's sort of true. There's only a brief introduction to the first-person adventure, giving you the basic set-up: Ethan Carter wrote a letter to Paranormal Paul, asking for his help. Beyond that, the game trusts you to discover how it works on your own. For example, it doesn't fabricate reasons for you to sprint or crouch in a tutorial segment, like most games do. There aren't quest arrows, and if you're not careful you can walk right past entire story elements without even noticing them. You can even solve the game's mysteries out of order. It’s cool with that.

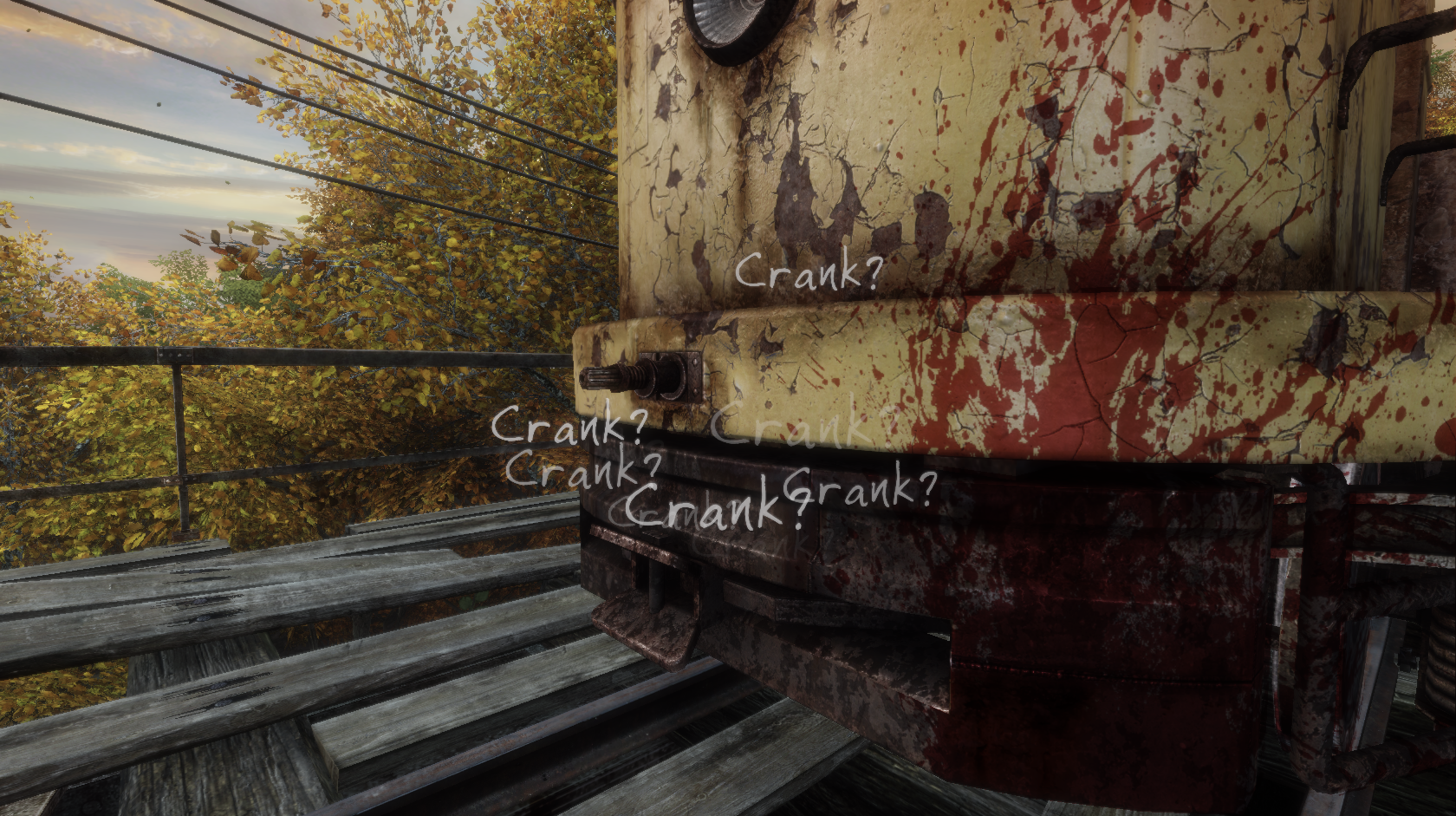

Then again, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter doesn't trust you entirely. It will draw your attention to the crankshaft on the nose of a stalled train, at which point the word Crank? will appear, duplicating itself, swirling in front of your eyes, flooding across the screen as if by pressurized hose with all the subtlety of a pop-up ad. Crank? Crank? Crank? Crank? Crank? Hold on. I'm getting a psychic message here... I think I need to find... a crank? And then crank it? Glad this game doesn't hold my hand. If you reach the end without finding everything, there's a handy map painted on a wall with, well, a bunch of quest arrows, directing you to the puzzles you missed. The point is, while The Vanishing of Ethan Carter doesn't hold your hand in the traditional sense, it still tries awfully hard to make sure you don't miss anything. Thankfully, it's well worth your time to not miss anything.

Specter inspector

At times the floating words, sometimes instructions, sometimes Paul's own internal musings, are absolutely necessary. No, I probably wouldn't have noticed a discolored patch of grass indicating that an object, long dormant there, had recently been moved. On the other hand, upon finding a bloodied corpse lying next to a fire axe, the words "Inspect" hovering over both... well, I might have sussed that out myself.

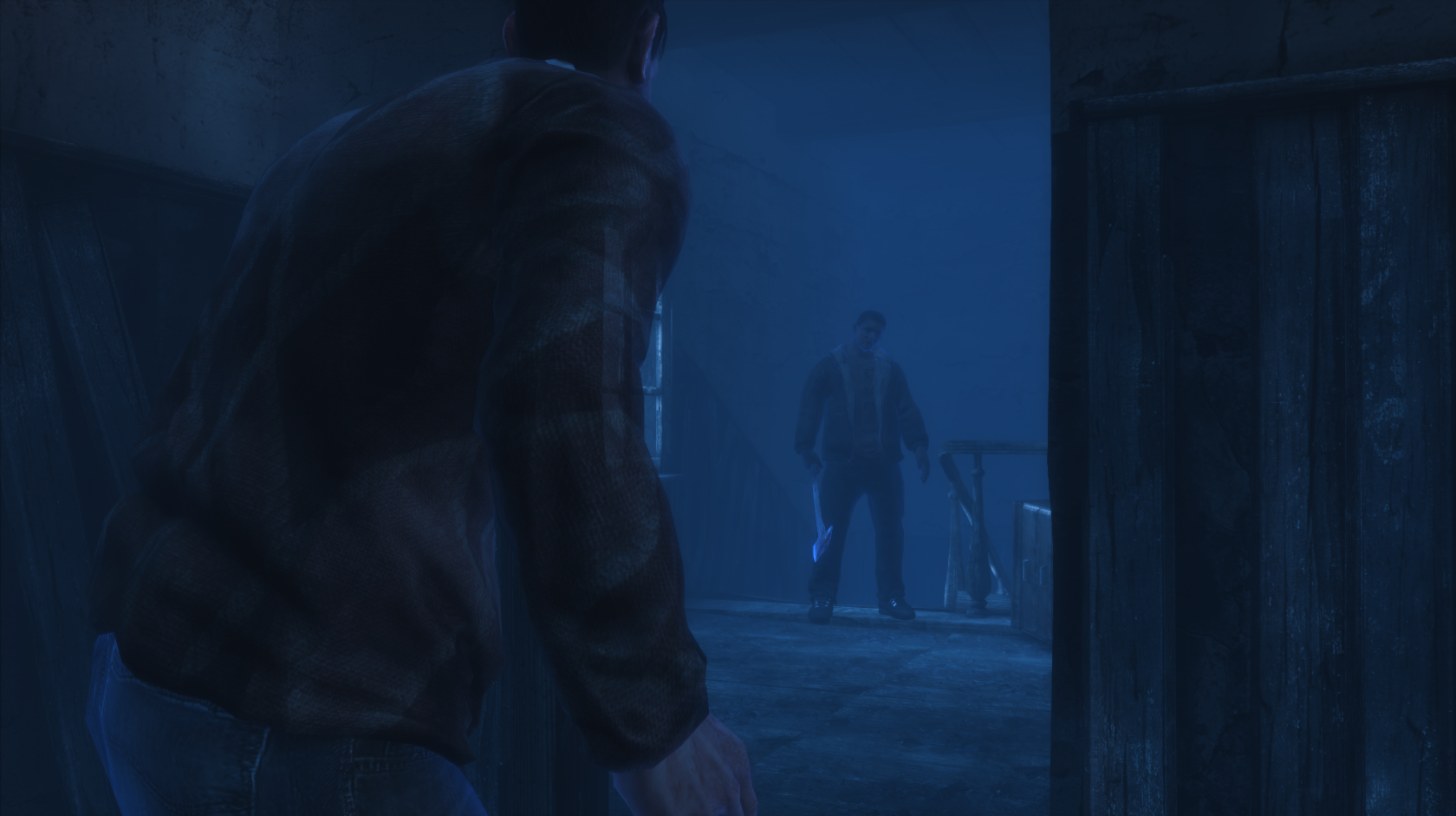

Paul's abilities don't end with tooltips floating above clues, rather, that's where they begin. After reconstructing a murder scene by finding and replacing a few items, he can conjure up the events that led to the bloody tableau. First, he sees them as a series of images: frozen holograms of ghosts, still and silent, in various phases of the murder. Once you've found them all, you'll need to put them in chronological order by assigning them numbers. Did the couple peer into the crypt before the murder in the graveyard? Or did that happen later?

Once you've assigned numbers to the ghosts, you can watch the entire scene unfold from start to finish in a spectral replay, provided you've ordered the scene correctly. If you don't, the scene will play until it reaches your mistake before dissipating, leaving you to make corrections and run the spook-reel again. It's an enjoyable activity, sort of like directing a movie without having seen the script. I found it positively thrilling the first time I completed one correctly, though unfortunately, it peaked with that first sequence. There a handful of such ghostly replays to manage, and the others are a bit more straightforward, the final one being so obvious it seems silly to even ask the player to number it. Still, even when it's easy, it's good fun.

There are a couple of other types of puzzles as well. One requires a fair bit of memorization, something I'm rotten at (I had to resort to taking screenshots and referring to them for comparison), another involves matching symbols and shapes to unlock a gate, and, naturally, there's a big water valve to turn (video games). I've seen these types of puzzles in games before, but even so, they're very well-made and satisfying to solve here.

Beauty and the mid-to-high-end PC

The Vanishing of Ethan Carter isn't really scary. It's eerie, certainly. It's spooky and unsettling. Despite there only being one real, genuine, board-certified jump-scare—cheap, sure, silly, yes, but still well done—there are plenty of other startling moments, and the general sense of dread and loneliness led to me jumping a number of other times, sometimes just at the sound of Paul's voice as he suddenly decided, after long minutes of silence, to muse out loud. The tension in Ethan Carter comes not from continuously trying to scare you, but from making you continuously think you might be scared at any moment. That's the best kind of tension, and it's entirely successful here.

It’s also gorgeous. It's the loveliest outdoor environment I've ever wandered around in. The lighting, the textures, and the attention paid to the foliage and landscape meant I'd wind up stopping every couple of minutes just to look around in admiration. Peering over the edge of the massive dam (and peering back up at it, later, from below), gazing at the sunbeams filtering through the trees, admiring the beautiful decay of abandoned buildings, staring across a bridge, crossing it, and then turning to stare across it from the other end.... I don't care if there are bloody corpses all over the place. I'd live in Red Creek Valley in a second, and possibly, for a second. On my PC—Intel i7 2.8 GhZ, 8GM RAM, Nvidia GeForce 660Ti—it ran remarkably smoothly on maximum settings for such a fine looking game.

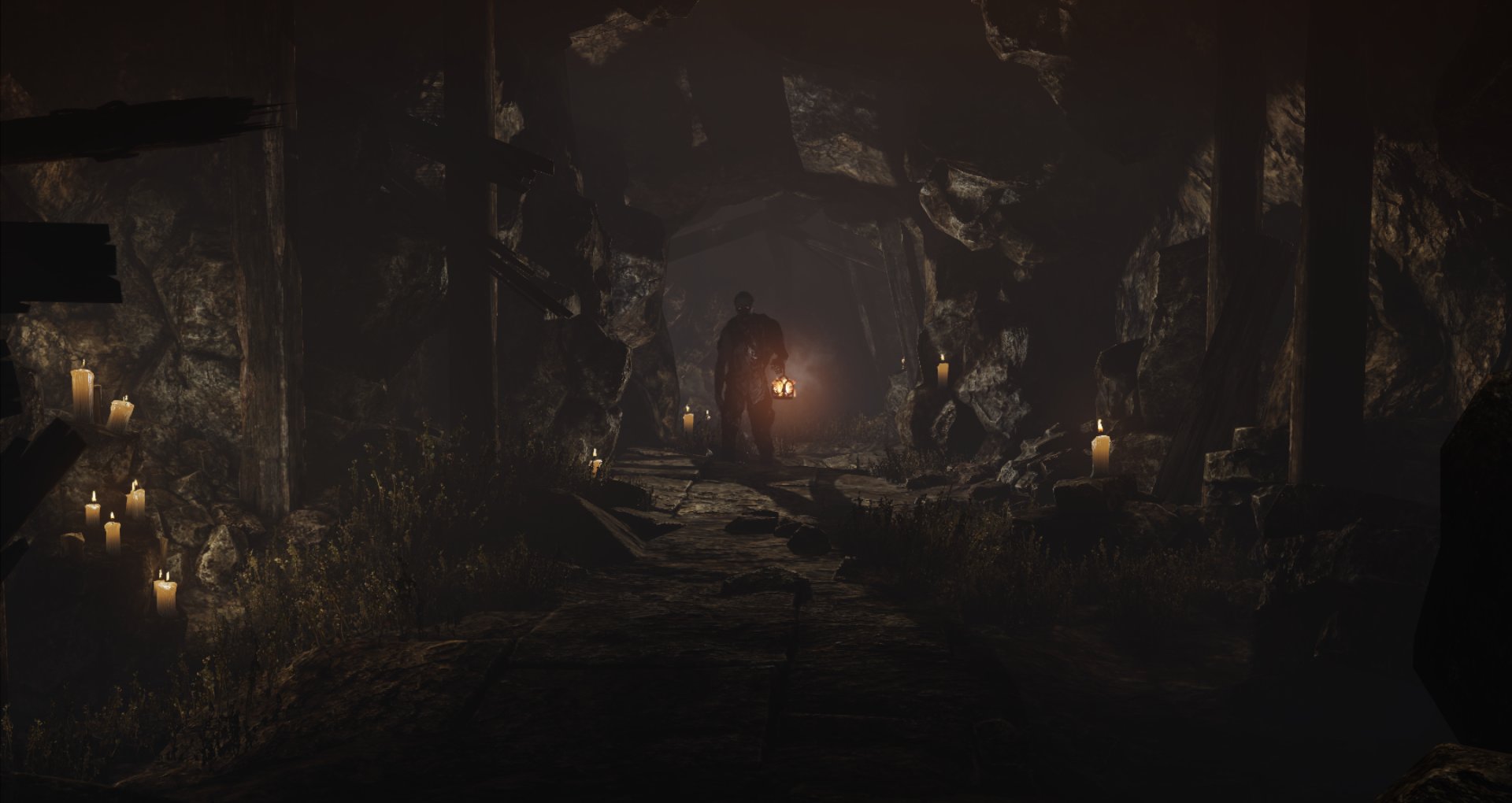

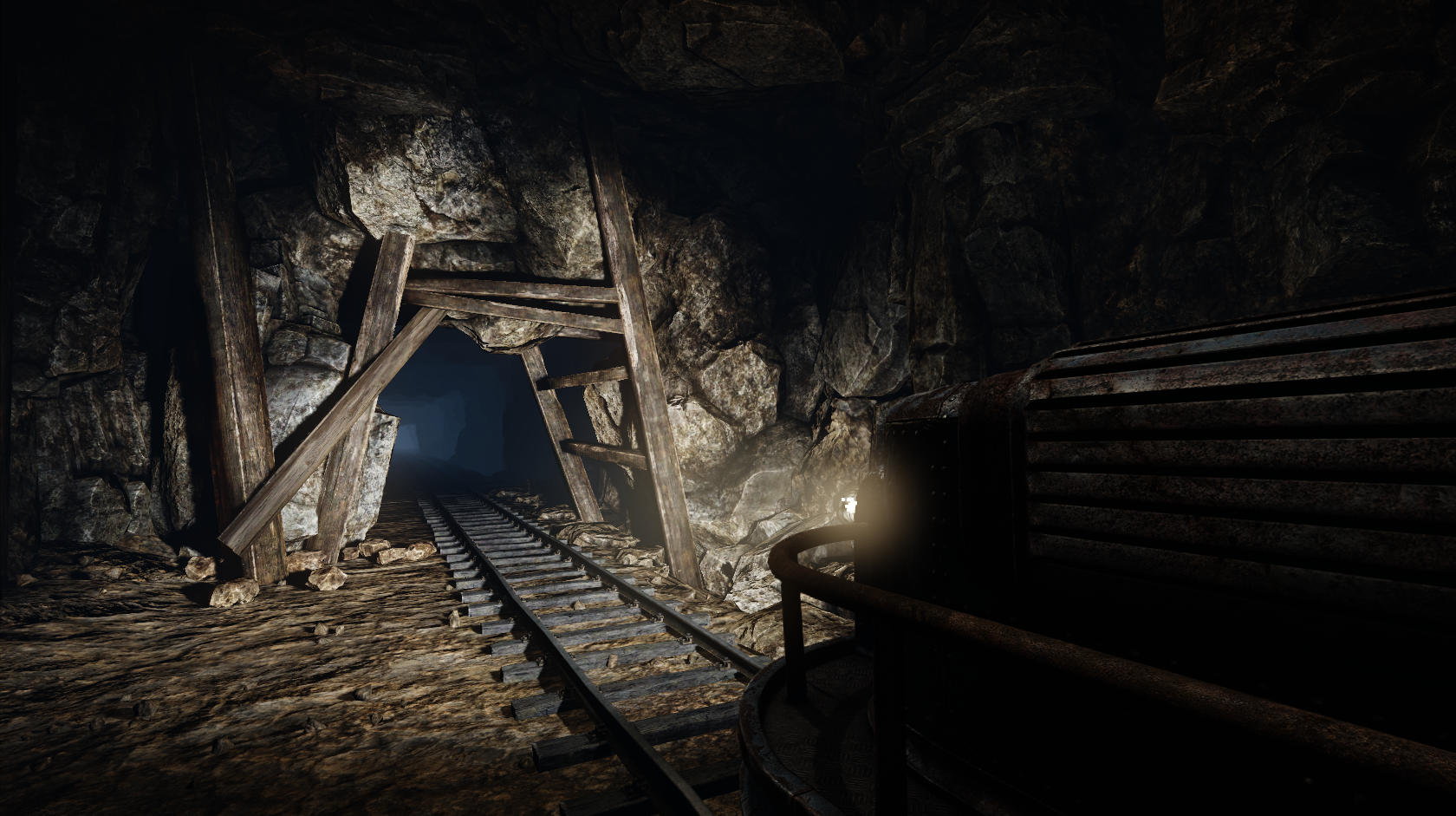

The beauty of the outside world makes it a major bummer to have to leave it during an overlong jaunt in a series of old mining tunnels, which is the game's weakest section. There's a lot of sprinting around in the dark, often in confusion, through winding, generically spooky, near-identical tunnels, where the initial heightened dread and fear quickly gave way to a "let's get this over with" mentality (though the puzzle at the end is fun).

The beautiful world is also extremely large, and while this isn't a complaint, I do have to note that it's not exactly stuffed with activities. There are several long stretches of trail, perfectly enjoyable to walk along and scenery-gaze, but with absolutely nothing going else on. Some will enjoy it, feeling a bit of a Dear Esther vibe; others, I'm sure, will wish there was a bit more to actually do. I enjoyed all my strolls (with the exception of running into invisible barriers occasionally), and never got bored: it's just too damn lovely for that. At times, though, a small part of me was thinking "I've been on this winding trail for ten minutes and found nothing.. are they gonna add some DLC mysteries in here or something?"

Quiet time

When it comes to story, especially one with supernatural elements, developers The Astronauts have exercised remarkable restraint. This is the first game in a long time where I never wanted to skip anything being said, and that's because not all that much is said. On Paul's long nature walks there's ample opportunity for him to be constantly spewing his thoughts and ideas, as protagonists often do when someone isn't calling them on the phone to spew their thought and ideas. While Paul does occasionally murmur some vague filler, he's always brief about it. Written clues are generally only a paragraph or two, and even the ghostly movies are quick and concise. I'm a guy who hammers at the space bar in Skyrim to skip the seemingly endless blather, and I went through much of the Bioshock games repeatedly yelling SHUT UP at the constant, endless stream of story being delivered to my radio. None of that here. Ethan Carter makes the most of its few words, and gives you plenty of silence to think about them yourself. I'm grateful.

As a game involving lots of careful exploration and zero rocket launchers, Ethan Carter will no doubt be described by some incredibly clever people as a "walking simulator." But how well does it really simulate walking when compared to other notable walking simulators?

Gone Home has players walking around a house. Ethan Carter has players walking around outside. Simulation-wise, practicing walking around a house seems much more likely to come in handy because we're in houses a lot.

Winner: Gone Home

"When will DayZ standalone get vehicles?" is the common wail of DayZ players, because they're tired of walking everywhere and there simply aren't any other games to fly helicopters in. Also, you can take your shoes off if you want.

Winner: DayZ

I walked around a couple times, in real life. Didn't care for it. Real life isn't as pretty as Ethan Carter, plus, I got tired and a little hungry.

Winner: Ethan Carter

I don't feel a game's total running time is of major importance, though I do understand weighing hours played against dollars spent, so here's how I rolled: my first run-through was about four and a half hours, and a good forty minutes of that was spent simply backtracking and poking around for anything I might have missed (and I did miss a few things). I suspect the cleverest and sprint-iest of players could complete the game in three hours. I think the length is just right. It's a short story. It doesn't need to be a novella.

With so much going for it, it's a shame Ethan Carter shoots itself in the foot by not letting me save my game manually. I was playing late at night, for full creepiness, and decided to call it quits and get some sleep. A warning popped up: quitting would lose the progress I'd made since my last autosave. When was my last autosave? No fucking idea. That's the problem with minimal on-screen elements: I never saw the autosave indicator. Fearing I might lose the past half-hour of work, during which I'd found many clues but hadn't solved a puzzle, I trudged on, trying to progress enough to force the game to save again. Twenty minutes later, I solved another puzzle at the other end of the map, though I was annoyed at having to rush through it just because I wanted to go to bed. What's more, when reloading the game the next morning, I'd been returned to the middle of the map, leaving me to wonder if the distant puzzle I'd solved the night before had been saved after all. It had, which I only found out after making another long trek back there.

That annoyance—I won't say it was minor, because it wasn't—was about the only thing I didn't enjoy about The Vanishing of Ethan Carter. Visually, it's spectacular. It's tense and the mysteries are enjoyable to solve even when they're not that hard. The voice acting is decent, and while I don't think the story paid off in spectacular fashion, I found it intriguing, mostly satisfying, and most importantly, wonderfully restrained.

A tense and spooky stroll through a gorgeous world, some fun supernatural detective work, and an efficient script with sparse dialogue.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.