The US Navy is training sea lions and dolphins to play videogames

No word on the Navy seals.

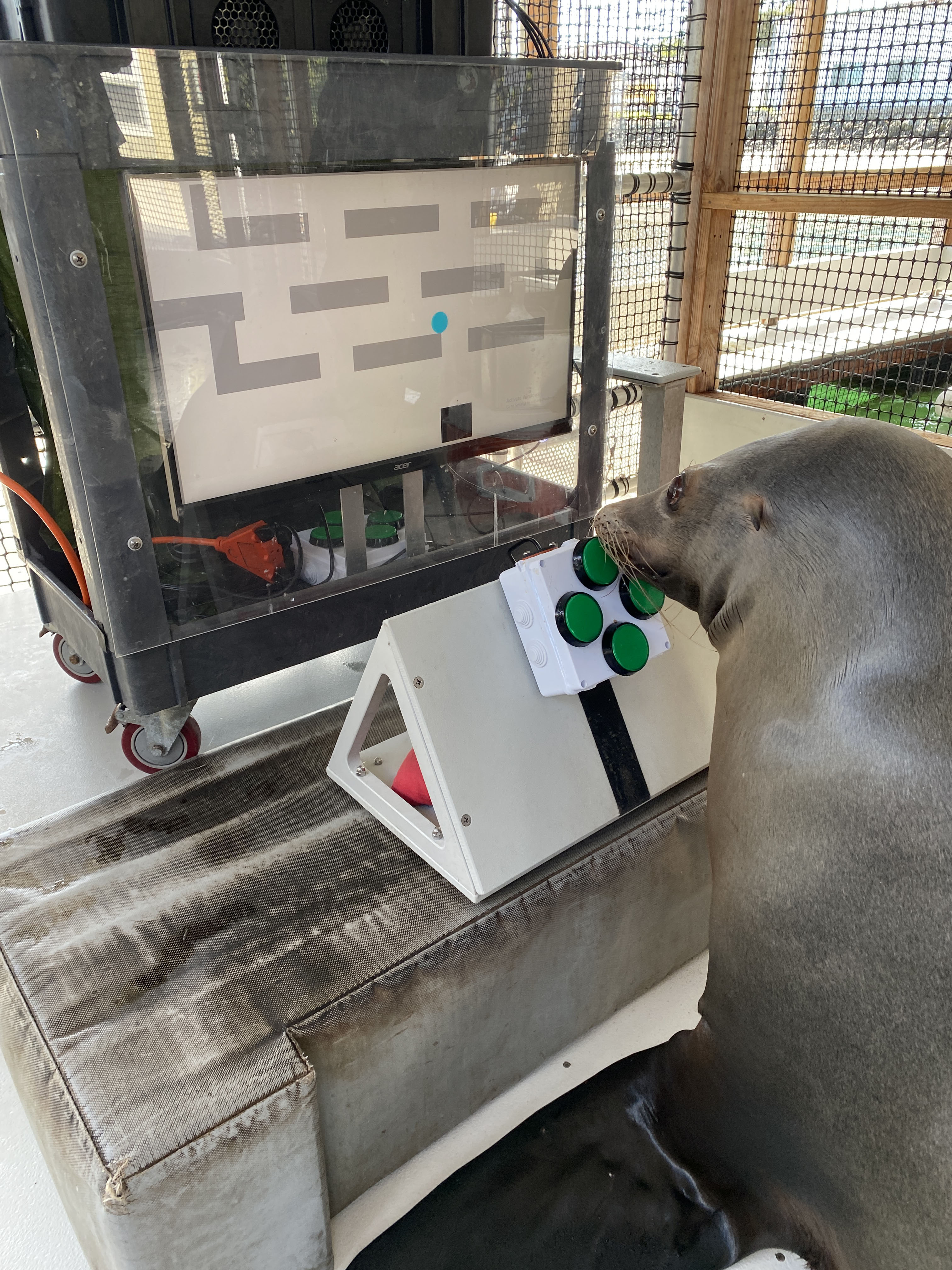

A new press release from the US Navy arrives with the rather eye-catching headline: "The Navy's Sea Lions Love Video Games." And the contents certainly deliver, focusing on a sea lion nicknamed Spike who's apparently "the most avid gamer in a sea pen floating in the San Diego Bay." Spike likes fish, napping, and playing a game system designed by Navy scientists to train marine mammals.

The Navy is very proud of Spike because, although he was the last of three male sea lions to learn how to play these videogames, he was the first to complete the full training program: He learned to understand the concept of controlling a cursor on a screen, then was gradually put through a series of more challenging games, with plenty of fishy rewards along the way. This apparently marks the first recorded success "in testing cognition of California sea lions with an animal-controlled interface."

The gamer sea lions are a project run by the US Navy Marine Mammal Program, which also has gamer bottlenose dolphins, and as well as training the mammals to perform various tasks the organisation believes the games offer "cognitive enrichment" and essentially keep the animals happier and healthier.

One of the games described is a simple maze game, where Spike has to manipulate the cursor to the exit. The navy press release describes it thus:

"On the deck of the sea pen, it’s pure delight: Spike uses his snout to press a button and maneuver a cursor through a maze. His eyes track the cursor with laser-like focus. When he crosses the finish line, we cheer and his trainer rewards him with herring. The joy in the eye contact between him and his trainer as they celebrate a job well done—Spike with his side-to-side dance and victory yelps—is palpable and infectious. He turns back to the screen and positions himself to win the next game."

OK, but what's his Elden Ring build? "I really care about these animals and the lives they lead," said Kelley Winship, NMMF scientist and principal investigator using the Enclosure Video Enrichment (EVE) system. "I love all the cool stuff we can look at with this research, but at the end of the day, I want to see them happy and enjoying themselves.”

Spike's been training over three years of (voluntary) sessions, some of which take place without the herring treats, and over this period apparently showed improved weight maintenance and overall health. The research has focused on whether the sea lions are having what can only be described as fun: Do they want to keep playing? The Navy eggheads reckon that the 750 sessions the sea lions have racked up means yes.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The EVE system that the animals train on is admittedly ingenious. It faced various requirements, such as having to be portable, being able to be disassembled and reassembled, and of course it had to be manipulable by pinnipeds (semi-aquatic, fin-footed marine mammals). It's a plastic utility cart with a 27-inch monitor, protected by acrylic glass, with a computer encased on top, an external speaker connected via bluetooth, and a USB controller consisting of four 2.4 inch plastic buttons.

The sea lions were first taught to notice the screen's stimuli and respond, before exploring the controllers unconnected to the games, before trainers began teaching them with points and prompts. The first 'game' they learn to play is moving a blue dot onto a black square, and over time the animals are moved onto more complex variations.

"Over time, Spike and his friends could switch directions when the cursor bumped up against a wall, complete levels at an average clip of six seconds, and win in fewer than seven button presses," says the Navy, sounding a bit like a proud dad. They also built an automatic feeder that linked to the system but, after early trials, discovered the sea lions preferred sessions where trainers fed and encouraged them.

"The research possibilities with this are endless," said Kelley Winship said. "We built a game where we can compete against Spike—he can chase us around and we can move away. He hasn’t seen it yet. He’s going to be really excited."

The Navy's also built an EVE system for bottlenose dolphins, which has a large projector screen visible from the water with joysticks the dolphins manipulate with their mouths in the water. The sessions take place after sunset so there's no sunlight interfering with the projector and apparently looks like an "eerie pierside movie night", with the Navy adding the detail that it could be a TV night because "the dolphins like watching 'SpongeBob Squarepants.'"

Well. Apparently the main difference between marine mammals and humans, when it comes to videogames, is that the animals show delight when they win but don't get frustrated when they lose. "You don’t really get a sea lion scoffing and throwing the controller down," said Kelley Winship.

If you ever wonder about whether the military has too much money, then let's merely note that about 300 people are employed to care for and train over 120 sea lions and dolphins. Their military purpose is officially being trained in "reconnaissance and recovery tasks marine mammals can perform better than humans" with the videogames, for now, regarded as more about their holistic care. But this is clearly about ultimately being able to train such animals in even more complex tasks using such tools: It's all fun and games until the day some enemy of the state is strolling along the quayside and is suddenly decapitated by a troupe of sea lions dressed like Dante.

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."