The story of the first esports champion, undefeated since 1972

Catching up with the man who won the inaugural Spacewar! Olympics, likely the world's first esports tournament, in 1972.

The story of the first esports tournament is the story of the American counterculture. At least, that's how the people who were there at the time talk about it. Stanford University, 1972, the dawn of the digital revolution, and an era of weed, psilocybin, free love, and Mao-style anti-capitalist communes. The U.S. was in the death throes of a failed war in Vietnam, and San Francisco vagabonds were protesting Nixon, programming prehistoric FTPs, and yes, playing a ton of Spacewar!

I was practicing using the buttons backwards, using the buttons left-handed... I was able to hold two boxes, with two button sets, and fly two ships

Bruce Baumgart

You can call Spacewar! the first video game ever made and get away with it most of the time. Yes that isn't technically true—the brutalist tic-tac-toe module OXO was developed in 1952, and the wonderfully nebulous Tennis For Two (which looks like two galaxies in the dead of space playing pong) arrived six years later in 1958. Still, Spacewar! had something that neither of those did, when MIT legend Steve Russell released the game in 1962: a playerbase.

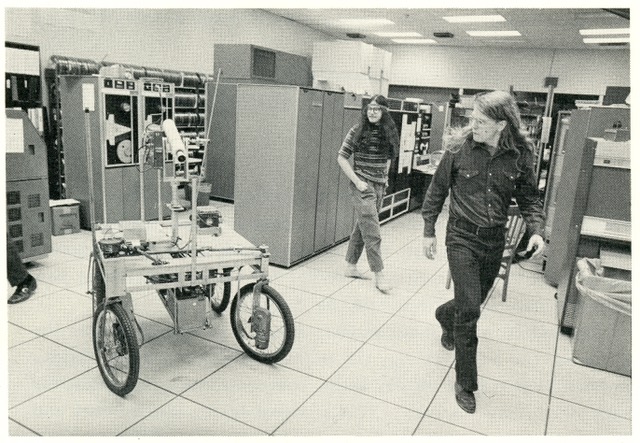

In the small, ultra-insular generation of programmers in the late '60s and early '70s, Spacewar! was cultivating the first degenerate gamers. Why? Because they were the only ones who had access to those warehouse-filling computers, and they got game time in whenever they could.

"You had 50 desperate students trying to get their homework done, their thesis done, their regular work. So using the time-sharing computer for Spacewar! was a really off-hours thing," says Bruce Baumgart, 72, who tells me that he still keeps his hair long, more than 40 years later. "For ordinary people, that meant they were giving up around 11pm or 12am, which meant that the machine was free and could tolerate a Spacewar! game or two. There were only six of those displays that could handle it. So if you didn't play Spacewar! you'd join the penny poker game."

For the history of Spacewar! and the PDP-1, the 'minicomputer' it ran on, check out this article.

Baumgart was a grad student at Stanford, and spent most of his waking hours in the A.I. lab. Today he's cultivated one of the more comprehensive careers in computer science, logging time at both IBM and the essential Internet Archive nonprofit. (Here he is, accepting an award for the archival project SAILDART.) But don't let those credentials distract you from the reality that Baumgart was one of the greatest Spacewar! players of all time—probably still is one of the greatest—and may well be videogames' first esports champion.

If you've never seen the game in action, it pits two spaceships against each other in a celestial gravity well, with Asteroids-style Newtonian drift in the controls and a limited number torpedoes to target the other player. It offered a surprising amount of depth for rudimentary software, which made it the first piece of digital entertainment with what you and I would call a "skillcap" today—much closer to computer chess than computer checkers.

"There was a pecking order, but I was very good at it. I was practicing using the buttons backwards, using the buttons left-handed, [so I could handicap myself] when playing beginners," he explained. "Pretty soon, I was able to hold two boxes, with two button sets, and fly two ships [at once.] The real secret is you don't look at the buttons, you just look at the screen and think 'move, shoot, go over there.' That's what you do with any skill, like riding a bicycle or shooting a bow and arrow."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The young programmers taking over the computer hall every night eventually decided to settle that pecking order once and for all in a formalized tournament. So Stewart Brand, a Rolling Stone writer and Stanford grad who was then 33, organized "The Intergalactic Spacewar! Olympics" on an October evening in 1972. Brand would later carve out a career as a long career as a publisher and eternal internet optimist, but back in those days he was just another rascally interloper, enjoying life on the cutting edge of tech with a confederacy of disciples in his wake.

We don't know for sure if Brand's Spacewar! Olympics was the first esports contest in history. It is entirely possible that, somewhere in the bowels of MIT or Rice, there were other trailblazing dorks organizing their own private Spacewar! brackets. But it's undeniable that this Stanford symposium was the first video game tournament on public record. We know this because Brand wrote about the showdown in great detail for a December issue of Rolling Stone, just five years after Jann Wenner dropped out of nearby Berkeley and founded the magazine.

The resulting article is hilarious if you go revisit now. It's a true relic of the Bay Area's flowerchild years. The early '70s incarnation of Rolling Stone was printed on smudgy newspaper leaflets and given life by gonzo icons like Hunter S. Thompson and Lester Bangs, who wrote with an impassioned (and often incomprehensible) druggy zeal. Brand had already started his own periodical called The Whole Earth Catalog, which proselytized self-sufficiency and mindful ecological practices years before our current climate fever pitch. Clearly he knew who he was trying to imitate and impress. Here's Brand's lede from the Rolling Stone piece, uncensored and unabridged.

"Ready or not, computers are coming to the people. That’s good news, maybe the best since psychedelics. It’s way off the track of the 'Computers - Threat or menace?' school of liberal criticism but surprisingly in line with the romantic fantasies of the forefathers of the science such as Norbert Wiener, Warren McCulloch, J.C.R. Licklider, John von Neumann and Vannevar Bush. The trend owes its health to an odd array of influences: The youthful fervor and firm dis-Establishmentarianism of the freaks who design computer science; an astonishingly enlightened research program from the very top of the Defense Department; an unexpected market-Banking movement by the manufacturers of small calculating machines, and an irrepressible midnight phenomenon known as Spacewar."

You get the idea. The legacy of the Spacewar! Olympics is important from a professorial perspective, and clearly Brand had a certain self-awareness about the juncture in history he found himself in, and what it might mean for the future of entertainment. But he probably didn't realize he was organizing the predecessor to tournaments that would be played in giant stadiums, for millions of dollars, watched live by millions of people around the world.

By and large, the people who were actually there that night don't recall the proceedings with a whole lot of gravity. There were about 20 competitors and three different competitions: a Royal Rumble-style five-player free-for-all, a singles tournament, and a duos bracket. First prize was, of course, a subscription to Rolling Stone. Big money, big prizes.

Lester Earnest, a pioneering computer scientist who is now 88, was one of the people in the room, and when I ask him what he remembered about that night, he was dismissive and matter-of-fact.

"I remember that a bunch of guys wanted beer, so I went out and bought some and brought it back," he says. "Generally people had a good time, and Bruce won it. So then he got to brag about that."

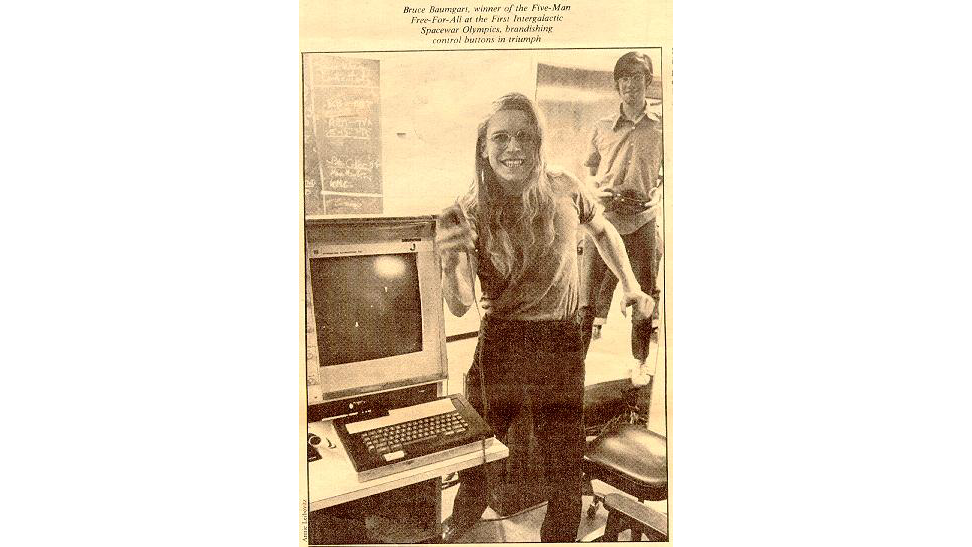

Specifically, Baumgart won the free-for-all contest, with what Brand would later describe as a "powerhouse performance" in his piece. Rolling Stone photographed his moment of victory—beaming face, messy long locks, and tortoise-shell glasses—and published it as the magazine's featured image. It might be stretching it to say he remains undefeated these 48 years, but as we have no record of another official Intergalactic Spacewar! Olympics, the champion reigns. To this day, Baumgart takes pride in his victory and his five seconds of fame.

"The article is [framed] right above me in my office," he says. "It keeps coming around every so often. I just felt like there was a huge wave happening. You could see that computers were going to explode. I was 26."

As the decades pile on, the most immortal thing about the tournament might be the pedigree of the attendees. The programmers each earned a certain amount of notoriety in their respective fields, but the woman snapping her camera that night was none other than Annie Leibovitz, who remains probably the single most famous magazine photographer on earth. She's taken portraits of everyone from Serena Williams to Queen Elizabeth. She was one of the last people to see (and certainly the last person to professionally photograph) John Lennon before his death. Somehow, the tragic fate of the Beatles and the dawn of esports have something in common.

Baumgart tells me that he keeps in touch with pretty much everyone who was involved in the Stanford computer department during his time at the school. They're still deep in the fringes of the Left, keeping the hippie rebirth alive for at least a few more years. "I'm running the reunions," he says. "As well as keeping the death watch. We joke about people kicking the bucket. It's completely different from when you're 20 or 30." When I reached him on a frigid Wednesday afternoon, he was in the process of preparing for a surgery the following week. You can't knock him out of commission for long, though. Even in their 70s, esports champions are a tenacious bunch.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.