The story of Battle.net

How Westwood's Monopoly and early internet gaming inspired Diablo's online gaming feature—and how it got its name.

It started, strangely, with the unlikely combination of a Hindu goddess and Monopoly. In 1995, Blizzard was flying high on the success of Warcraft and Warcraft 2. After years of small-time Super Nintendo games, they were suddenly big league. But there was one thing Warcaft 2 was missing: support for playing multiplayer matches over the internet. PC gamers, as always, were finding creative solutions to even the most challenging technical problems.

"We think this internet thing is going to be really big," recalls Rob Bridenbecker, Blizzard's VP of technology strategy and planning. "In 1995 we had Warcraft 2, and we obviously had support for LAN plan, direct link modems and what have you, but there was this really cool service called Kali where people would participate online against one another … Equally at the time we were noticing other services, I think there was mPlayer, Ten, and there was another one which was Westwood Chat. I think it was games of Monopoly you could play over Westwood Chat at the time. We thought, 'God, how cool would it be if we could create a network that was deeply integrated with our products such that people could connect up, play, it would be one click of a button, and they'd be online, able to communicate, chat, play with their friends?'"

For Blizzard's 25th anniversary, we're running a week of stories about its games, with interviews from veterans of the studio. Check out our history of every Blizzard PC game.

And then Blizzard came up with the twist: this bold new platform they envisioned would be free, because that's what they would want as players. And Battle.net was born.

Well, more like the idea of Battle.net. Today, Battle.net hosts tens of millions of active players across Blizzard's library of games, from Starcraft 2 to Overwatch. It's a little hard to believe how humble the origins of Battle.net actually were. In the early days, it literally ran on a single server, a PC under a desk at Blizzard HQ. But 21 years ago, when Rob Bridenbecker started at Blizzard, Battle.net didn't exist yet. Plans were gestating alongside the development of Blizzard's next game.

"The development of Battle.net felt like it went hand-in-hand with the development of Diablo," says Blizzard co-founder Frank Pearce. We knew before we launched Diablo—not early on but certainly as we were heading down the stretch—that we were going to have Diablo on Battle.net. A lot of the things that we needed to support multiplayer on Diablo were features we needed to implement in Battle.net."

At the time, playing games over the internet wasn't just novel. It was hard. In 1995, AOL still charged an hourly fee and Microsoft released the first version of Internet Explorer. Most multiplayer games were played over local networks or with two PCs connected with a null modem cable, and hauling a CRT over to a friend's house wasn't easy.

Playing games over the internet wasn't just novel. It was hard.

Services like Kali (still alive today!) would essentially trick games designed for LAN play into sending data over the internet, but they required configuration and didn't play nice with all games. Kali worked with Warcraft 2, but because the game was designed to keep data in sync between its players, the latency of a sketchy dial-up connection could muck things up. When Blizzard started building its own network platform, it had to find a way to avoid that problem.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"I'd be lying if I told you that we had a ton of experience at Blizzard at the time," Bridenbecker says. "A lot of it was guys that were super passionate about it and wanted to figure out how to do it, and we kinda learned on the job. Along the way we probably made as many wins as we did missteps. With a lot of the emerging technology back then, you'd come in and there'd be a new challenge. You'd come in and feel like you scored a victory, and then something bad would happen and you'd replay yesterday's events all over again."

Blizzard has a penchant for distilling complex genres down to an approachable, polished core—WoW compared to Everquest, Heroes of the Storm compared to Dota—and even 20 years ago, it was taking a similar approach to developing an online gaming platform. Blizzard co-founder and CEO Michael Morhaime remembers thinking a free, easy-to-use online platform could become a feature instead of a service.

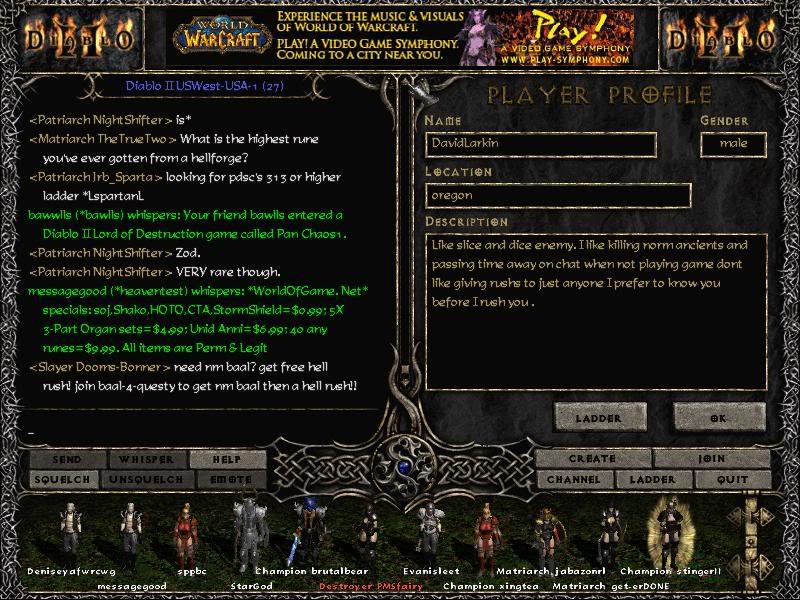

Battle.net's secret, in the early days, was how simple it really was. It was easy for gamers, but more importantly, it was cheap. Diablo, launched in December 1996, used peer-to-peer networking. One player's system would be host, and the rest would be clients—a common setup that's now largely (though not entirely) been replaced by dedicated servers. Battle.net was, more or less, a fancy IRC chatroom. There were no accounts. You could log in with one username, log out, and jump right back on with another. But with no dedicated servers, it was also an incredibly lean platform.

"Battle.net itself, in the old days, was actually a pretty awesome piece of technology," says Bridenbecker. "It didn't require much horsepower, which was our big trade secret. We didn't want it to be known, 'Wow, one computer is actually driving a few hundred thousand players all connecting at the same time.' A lot of that was because of the infrastructure on the games. The games themselves were peer-to-peer, so Battle.net had to be responsible for chat and getting those game listings up and matching players together. But once we did that, we were good. We stepped back."

In the early days of Battle.net, text chat, of all things, was its biggest bottleneck. In the late 90s, chatting online was still very much a novelty, and booting up Diablo and chatting with other players was the easiest way to make friends to go exploring with—just without the convenience of a friends list. That came later. In the beginning, Battle.net really had to be lean, because Blizzard was figuring things out as they went—and they didn't exactly have the most advanced technology to work with, either.

"Most of our systems were actually pretty crappy," Bridenbecker says. "We just didn't have these massive budgets to operate within. We were pretty thin, I want to say. Mike rocked a sweet Pentium. Maybe it was a Pentium 90. I had a 486DX2 myself … Over time we eventually graduated to a nice T1 [office internet connection], and eventually we did get to a T3 45 megabits a second line, but it took longer than you might imagine. We certainly didn't start there."

Battle.net was so lean, in fact, that in 1997 Bridenbecker loaded a copy of the software onto his laptop and took it to the Starcraft world premiere event in Seattle. The laptop ran the networking services for all the Starcraft matches at the premiere event, and relayed data back to the primary Battle.net server. "And it worked great," he said. Not bad for a laptop that probably wasn't much better than the one Chandler used to make spreadsheets in '95.

Growing pains

Blizzard's first big mistake with Battle.net was trusting client PCs. In Diablo, character saves were stored on the local machine, making it easy for players to hack into them before going online. Cheaters were as common as Diablo's minions.

Blizzard learned fast. With Starcraft, Blizzard pulled back from the chaos of complete anonymity by adding an account system. And with Diablo 2, they moved to a dedicated server system and saved character profiles server-side, limiting (but hardly removing) the potential for cheating. Battle.net grew to more and better servers as Blizzard began using its servers to host games, not just chat channels.

By the time Warcraft 3 came out a few years later, registering a name on Battle.net was becoming a problem, so they had to find a solution.

"The number of Bobs in the world seems to outnumber the ways you could spell Bob, and we kinda got bummed about that," Bridenbecker says. "So we had to namespace Warcraft 3 separately. I think you have to message it this way to this day, where there's a W#, and then the actual display name, and we did some magical-fu on the backend to allow it to all work together. But we started to reach some of the limits of that classic Battle.net infrastructure service right around those Warcraft 3 days."

The next big launch for Blizzard was 2004's World of Warcraft, but the MMO used its own launcher, with no Battle.net integration to be found. As WoW's subscriber count climbed and climbed to more than 10 million players, Battle.net and Blizzard's other franchises mostly laid dormant.

When 2009 rolled around, Blizzard announced a big update for its online services, Battle.net 2.0, which finally integrated World of Warcraft five years after launch. WoW and Battle.net accounts were merged, allowing for cross-realm and cross-game chat. Battle.net 2.0 was more sequel than update, really—Blizzard built up new network infrastructure and matchmaking systems that existed alongside "classic" Battle.net, leaving its legacy games to run on the deprecated version. This wasn't quite how things were originally meant to work.

At the time Battle.net 2.0 was taking shape, project lead Greg Canessa—who led the team that developed Xbox Live prior to working at Blizzard—said that Blizzard were looking at updating the classic games to the new service. There were other plans, too, that didn't come about. Blizzard "definitely built many aspects of the new Battle.net design around scenarios like DotA," Canessa said in 2009. "We want to be able to facilitate the community creating the next DotA for Starcraft 2. I mean that is definitely a design goal of ours."

Starcraft 2 was meant to launch with a marketplace that would allow for free trade and selling of mods and maps, but that didn't materialize, either.

In 2010, Blizzard faced a massive backlash over plans to integrate its use-your-real-name Real ID system into the WoW forums, and quickly backed off. But Real ID stayed a part of Battle.net, and some of Blizzard's modern streamlining decisions, once the draw of Battle.net, bothered players.

"We do try to err on the side of the player when it comes to introducing the ecosystem that we see, and how people can interact with the games," Bridenbecker says. "There were always some questions about whether or not we could open up more of our services—things like when we would deprecate LAN play out of future RTSes or future titles, those were definitely issues where we had a good dialogue with our community about. But I think in the end it came back to: what allows people to connect with one another in a very seamless and integrated fashion, such that they walk away feeling like it's a really positive player experience that anybody can participate in."

You can see that design sensibility shine through in Overwatch, which quickly matchmakes players, gives warnings about unbalanced team compositions, and emphasizes feeling cool and powerful over watching your kill/death ratio. And it's hard to argue against the convenience of chatting with a friend playing Hearthstone while farming in WoW, or jumping from an Overwatch match to a friend's Diablo 3 run.

But with Battle.net 2.0, those conveniences have come at the cost of some of the 90s' free spirited openness. Diablo 3 is an always-online game with no mod support. StarCraft 2 has no LAN support, and never got its planned marketplace, but it does have an editor and the Arcade, which promotes community mods and maps.

Hopefully there's more of that in Blizzard's future; as for Battle.net, its run almost came to an end when Blizzard dropped the name Battle.net in favor of 'the Blizzard App', a more grown-up badge for an online ecosystem. It didn't last. In 2017 they brought the Battle.net name back.

The .net may seem quaint today, but in 1995, Blizzard had to fight for it. "It was actually kind of a pain in the ass to get the name, because the top level domain .net was reserved for infrastructure companies, ISPs, and what have you," says Rob Bridenbecker. "We had to write a note to the governing authority for the TLD saying here's what we're looking to do with Battle.net, and we want to create a gaming service, in order for them to release the domain to us. It was very much a conscious decision. We kicked around a couple other names—I want to say the only one that [came close] was Storm.net—but Battle.net was the one that really stuck with us.

And why Battle? Simply:

"We thought it was cool!"

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).