The story behind Liberty Island, Deus Ex's most iconic level

Making a masterpiece.

This article was originally published October 1, 2019. We're reposting it today to celebrate Deus Ex's 20th anniversary.

Since its release in the summer of 1999, Deus Ex has become one of the most beloved games on PC. Set in a bleak cyberpunk future, Ion Storm’s ambitious first-person RPG, which was directed by Warren Spector, features deep systems, sprawling levels, emergent play, and a thrilling, conspiracy-laden plot. But one afternoon in Austin, Texas, where the game was developed, designer Harvey Smith and other members of the team were convinced that the game they’d been working on for years was destined for failure.

“We brought in Caroline Spector, Warren’s wife, and she was the first person outside of the team to play it,” says Smith. “She got off the boat at the dock and she picked up a box and threw it into the water. She got into the water and swam around. She tried to interact with a seagull. Then she tried to float on top of the crate.”

It’s worth noting that, in 1999, being able to manipulate physics objects like this in a realistic, simulated world was more of a novelty. And so this experimentation continued for 20 minutes as Harvey and the others watched over her shoulder, suddenly filled with dread. “We were gnashing our teeth,” remembers Smith. “We were like ‘God, we’ve fucking failed. She’s not even starting the mission! She’s just screwing around on the dock with all the stuff I put on there’.”

But then, suddenly, she turned to the anxious developers and told them in no uncertain terms that this was the most fun she’d ever had playing a game. “We were like ‘Holy shit! She enjoyed that?’. So we just doubled down on these quiet moments in the levels and the object physics. We already believed in these things ourselves, but it was very validating to hear it from someone else.”

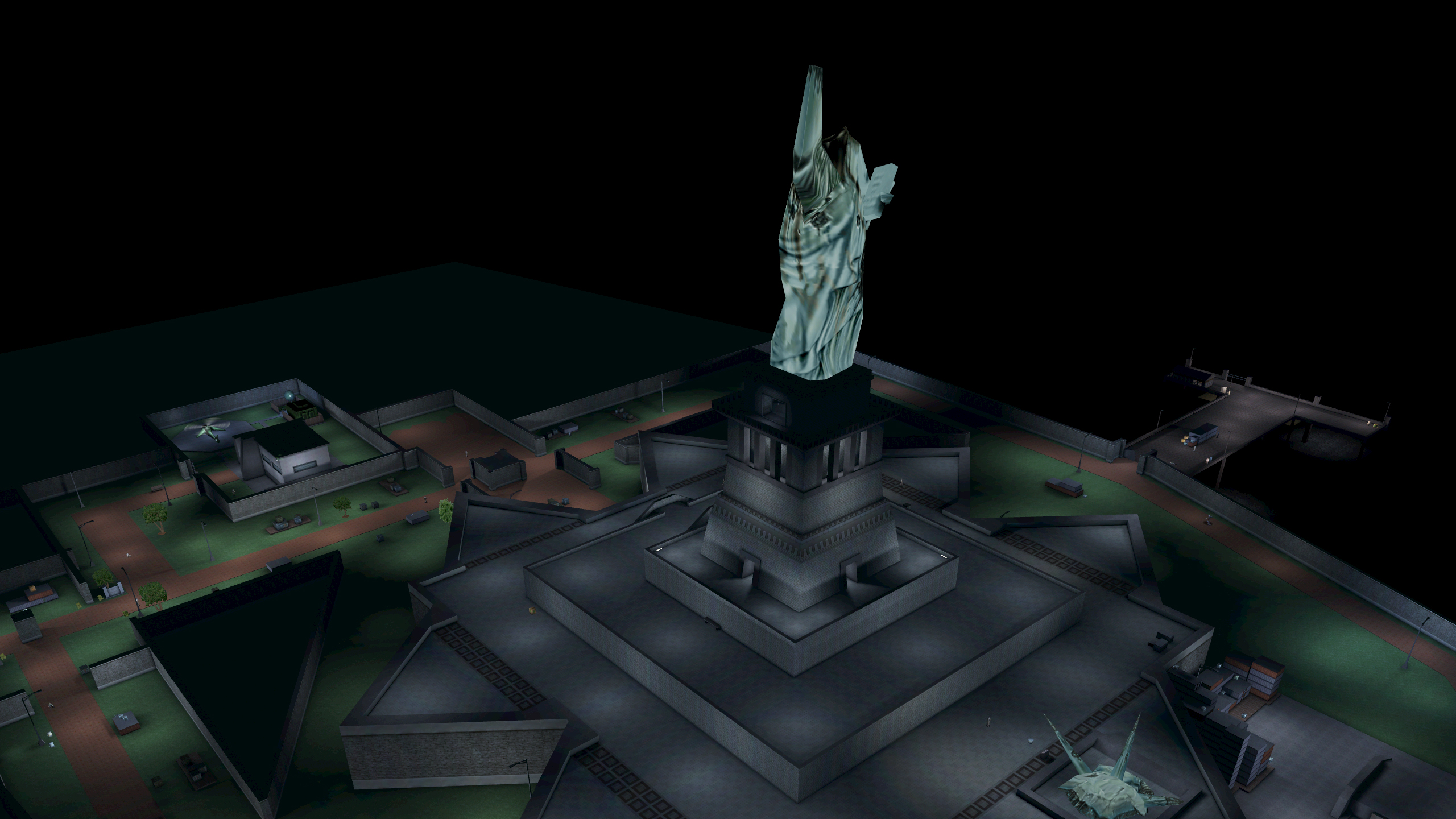

Liberty Island, where New York City’s famous Statue of Liberty is perched, is the first level in Deus Ex. It’s a trial by fire, thrusting newly minted anti-terror agent JC Denton into the middle of a terrorist occupation of the island. It’s also the perfect introduction to Deus Ex’s unsurpassed freedom of play, with multiple ways to infiltrate the complex and deal with the terrorists holed up there.

“Warren had grown up in New York and he wanted to feature locations like Battery Park and Liberty Island,” says Smith, who was behind much of the design of Liberty Island and other locations in Deus Ex. “And honestly, as a kid from Texas, I had no idea about these places and had never even visited them. But I still ended up inheriting a bunch of those maps, and it was Liberty Island that excited me the most because it was this big, open space.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“I’d seen corridors, streets, and alleys before in games. But what I really wanted to do was make a wide open space with something big in the middle that you could go left or right around. I could put tunnels under it, I could make it multi-tiered so you could climb to the top. That felt really different and exciting.

“When we shipped the game, Liberty Island ran at five frames per second on some machines. We’d see the frame rate nosedive because we had too many characters and the sight lines were too long. But we were making these huge, open levels because that’s the kind of game we wanted to make. A go anywhere game.”

Going underground

Once Denton has successfully dealt with the terrorist attack he returns to his headquarters for a debriefing—which, conveniently enough, is also located on Liberty Island. The underground UNATCO base, one of Deus Ex’s most memorable locations, is stuffed with characters to meet, secrets to discover, and world-building to ingest. But, Smith reveals, the game wasn’t always structured this way.

“The original idea was that you turn up for your first day of work, get briefed, and meet your colleagues,” says Smith. The first Ultima Underworld, one of Smith’s favourite games, begins with the player in a hostile environment. The sequel, which he found wildly disappointing, starts with you hanging out in a castle chatting to people. “So rather than open Deus Ex with Denton turning up at the office, we started with the mission instead.

“It was one of those epiphanies that comes mid-stream. By reversing this one thing, it changed everything. What if the terrorist attack was happening on your first day at work? It’s completely ludicrous and implausible, of course. But nonetheless, it was fun. You were immediately solving problems and doing shit.”

This way, getting into UNATCO—the entrance to which is tantalisingly locked when you first encounter it—is a reward for completing the mission. “It also gave us the chance to reflect on how you played,” says Smith. “Which direction you took, what objectives you completed, who you met, and whether you behaved ethically.”

An example of this is killing the unarmed terrorist leader you find at the top of the statue—do so and you’ll be harshly reprimanded. On the other hand, if you knock the terrorists out rather than kill them you’ll be commended for it. By some characters, anyway—the UNATCO grunts are not impressed by your pacifist methodology. This kind of granular reactivity defines Deus Ex, and was made possible by the limitations of the technology the game was built on.

“Because the fidelity was so low, this wasn’t that hard to do,” says Smith. “That’s the problem with games now—the fidelity is so high that to support something you have to do it well. That’s a lot of work, which means you can only support so many things. But in Deus Ex we could just throw you a datalink or have some guy flapping his muppet mouth at you. We actually had this simple tech that would analyse audio files so NPCs’ mouths kinda matched what was being said.

“We could also change the text in an email at the last minute or even easily re-record a line of dialogue because the guy who voiced JC [Jay Anthony Franke] worked in Dallas at Ion Storm. We tried to do the same in Dishonored, to account for everything a player would do, but it was much heavier lifting in that game.”

Liberty Island is a difficult level, especially if it’s your first time playing the game. If Deus Ex was made today it would likely be laden with tutorials, pop-up hints, and other hand- holding. “It’s almost like a test,” says Smith. “All the systems are in place in that level. But we did backtrack and add some things to ease you in.” This included JC’s brother, Paul Denton, meeting you on the south dock and offering you a selection of weapons to suit different play styles.

“I’ve always said that if you make your game super streamlined then you try to add depth later, that’s a hard road to walk,” says Smith.

“But if you make it as deep, emergent, and layered as possible, but then you figure out how to ease people into that, the end result is much better. Liberty Island was us testing that theory.”

But making design decisions like this was never easy at Ion Storm. Although Smith enjoyed working there, things were often made difficult by conflicting opinions about what Deus Ex should be. “The team was a weird combination of tech nerds and pen-and-paper nerds coming together,” he says.

“A more narrow slice of society than we have in game dev now. The industry is definitely more interesting and a lot more diverse now. That said, I loved Ion Storm, and I learned a lot from every single person I worked with there. But there was a schism. Three different factions were at odds, and that often involved trying to convince Warren that we were making one kind of game and not another. One part of the team, some of whom had come from shooter backgrounds, wanted to make an FPS like GoldenEye. Another group came from Origin and wanted to make an Origin-style role-playing game, but from a first-person perspective. Another was in love with Looking Glass, specifically Ultima Underworld and System Shock.”

This led to fights and compromises. One team would feel bad that they lost, another would be delighted that their values won out, and vice versa. “Some of us wanted the speed, movement, and precision of a modern first-person shooter,” says Smith. “Others wanted the world-building and atmosphere of a Looking Glass game. Then, over time, these elements began to overlap.”

Free rein

Liberty Island was a source of conflict, particularly when it came to determining how much freedom the player should be afforded at this early stage of the game. “We had people on the team who thought the first level should be about using one set of powers, then the next should be about another set,” says Smith. “A lot of classic games are structured like that, but another group of us thought that everything in Deus Ex should be possible all the time. It should be your decisions as a player that drive you, not the game itself.”

Some people also thought that each style of play should be clearly delineated: a branching hallway, for instance, would lead to a stealth path and a combat path. “But we thought there should be the potential for stealth and combat in each hallway,” says Smith. “If you do that wrong it gets messy and doesn’t have any identity. But we developed rules about encounter spaces, like having a negative space between them to give the player contrast. That’s why there are empty areas on Liberty Island, to give you quiet, reflective moments.”

About halfway through the development of Deus Ex it was decided that every level should support stealth, combat, and hacking. “You can have other stuff too, like maybe a bribery path,” says Smith. “Giving a guard some money to turn the other way, something like that. But overall those three styles had to be fluidly supported.

“One thing that really helped us, and I don’t think this gets enough attention, is that during the development of Deus Ex, System Shock 2, one of the Thief games, and Half-Life came out,” adds Smith. “So we had the opportunity to play these games and take things away from them. That really helped Deus Ex.”

While Deus Ex was a team effort created by many talented people, the nature of game development at the turn of the millennium meant that Smith was able to get much more hands-on than he can today, even down to designing individual props for the levels. “To get anything into a game these days, even a chair, you need a massive army of people, sometimes using external dev partners,” he says. “So everything has to be super documented and thought about. It goes out, it comes back, you make adjustments. It’s a huge undertaking.

“But when we were making Deus Ex I spent one day in Unreal vertex-manipulating various pieces of furniture. I made tables, chairs, beds, everything. Then I made a separate level on the network that was just called ‘furniture’ or whatever, and it was full of them for people to use. This isn’t a humble brag. It’s just that, back then, one person could jam out of a lot of stuff. Now we have an environment team, an architecture team, and a level design team.”

Almost 20 years later, people are still playing Deus Ex, evidence of the depth and quality of its design, not to mention the talent and vision of the people who designed it. It’s amazing that from such a conflicted studio emerged a game that has so firmly stood the test of time. It may look uglier with every passing year, but Deus Ex remains an eminently playable game. Liberty Island is one of the greatest opening gambits in PC gaming and the lessons Smith learned making it have served him well over the years, notably in the wonderful Dishonored series, which he directed. “Along with Dishonored,” he says. “Deus Ex is one of the few times in my career where I’ve just non-stop played a game I’ve been working on and it hasn’t felt like a chore.”

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.