The most important PC games of the decade

25 influential games that defined 2010-2019.

We write all the time about the best games you can play on PC, but the end of the decade is an invitation to examine which games have changed PC gaming itself. This list of 25 is our memory of games that continue to matter for their themes, for their impact on the business or technology of games, for reshaping the relationship between players and developers, for having formed a new genre, or for failing spectacularly. Not all of these games released between 2010 and 2019—following one of the biggest trends of this decade, some PC games have had tectonic effects on our hobby long after their launch day.

EVE Online (2003-onward)

EVE Online is the closest we've come to that sci-fi dream of living a second life in a virtual society. At this point it's less of a game and more like an alternate reality where players can become warlords, dictators, or just another scummy pirate blowing up poor space truckers for shits and giggles. But the point is that, unlike so many other of the best MMOs, EVE Online is the only one courageous enough to let players define their own experience—for the most part.

Where other MMOs hem you in with authored narratives or limited player interactions, EVE Online's developers are remarkably willing to sit back and let players steer. The result is a player-driven world with a real economy and a tangible sense of consequence, which in turn gives every action a sense of weight and meaning rarely found in other games. In EVE Online, the wrong move and undo years of work.

What's really monumental, however, is the sheer scale of that collective fantasy. Because every player inhabits the same universe, EVE Online has become an enormously diverse digital society with its own recorded histories and cultures that wax and wane as player-built empires rise and fall. Those tectonic shifts in EVE Online's landscape are felt through the first-hand experiences of the players themselves, personal stories of betrayal, discovery, and camaraderie that carry the same emotional gravity as if they happened in real life. Therein lies EVE Online's lasting legacy, that uncanny ability to make a collective fiction feel real. No game other game has managed that—not at the same scale—and I'm terrified that no other game will manage it again. —Steven Messner, Senior Reporter

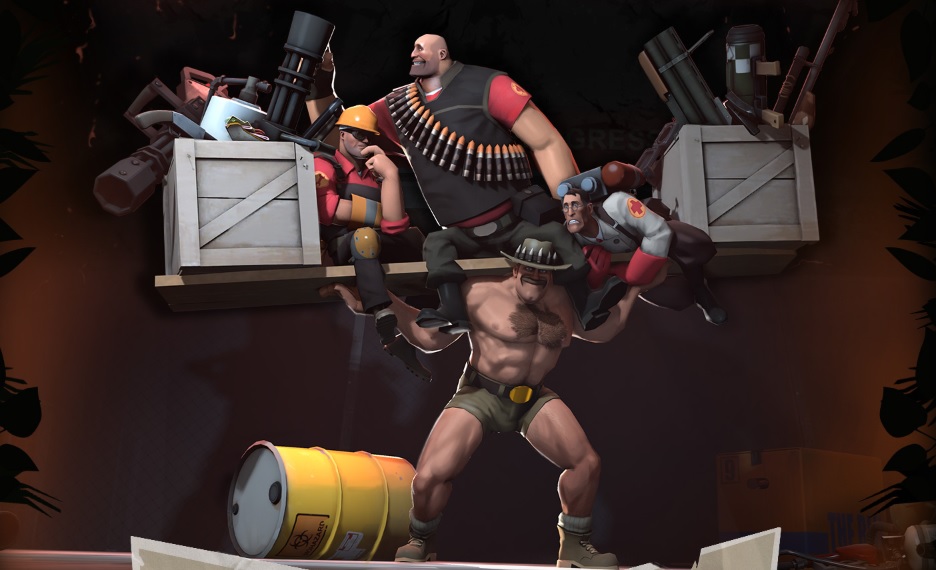

Team Fortress 2 (2007)

Between 2009 and 2012, Valve subjected its FPS to an amount of change and experimentation that would have killed a lesser game. What launched as the stylish comeback of a 1999 shooter became a guinea pig for Valve's ideas and larger initiatives. In the process, RED vs. BLU became a platform for inventive storytelling, new technology, and business models that would change Steam and PC gaming forever.

Crawl the list of 684 updates (and counting), and you notice the escalating pokes, prods, and full-body transplants Valve performed on TF2. What if we released new items for characters that transformed the meta? What if we sold those items? What if anyone could make items, sell them in our game, and make money from it? Can we put an RPG-style crafting system in a multiplayer game? What happens if we use this item economy to promote the launch of dozens of other games on Steam?

In 2011, "going free-to-play" was an unusual move for any FPS, and for western-developed games especially. Team Fortress 2's shift from a paid game to a now-mainstream microtransaction model invited other developers to adopt the same scheme. Valve's biggest stroke of brilliance was the way that TF2 entangled narrative with all of these changes. The surprise addition of co-op to a five-year-old competitive game wasn't a desperate gimmick, it was an invasion of robots within a surprisingly intricate family feud storyline paired with its own trailer, ARG, webcomic, cosmetic items, microsite, and special set of "Machievements." A replay system wasn't just a new feature, but the debut of an annual community film festival—a handful of winners would receive one of the rarest in-game items: the Saxxy, an Oscar trophy wieldable as a melee weapon, and the golden incarnation of TF2's insane, long-running obsession with Australia.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

This is the true impact of TF2: using storytelling to add meaning to game updates. We see it in every major competitive game that's followed, from Rainbow Six Siege to Overwatch. In July, PUBG introduced its Season 4 with a Story Trailer. Fortnite's ambitious brand cameos are built on TF2's playful hat tie-ins.

Lab rats are supposed to eventually die. Instead, these mad experiments made TF2 stronger, and the entire industry learned from Valve's discoveries. —Evan Lahti, Global Editor-in-Chief

Minecraft (2009)

Selling a game before it's finished is practically the industry standard these days, but before Kickstarter, Steam Early Access, Fig, and other crowdfunding tools became popular, there was Minecraft. In 2009 it was in an alpha state, nowhere near feature complete with years of development still ahead. But its barebones free alpha had received a positive, excited response and developer Markus Persson decided it was time to start making the money needed to fuel the rest of its development. The alpha went on sale in June of 2009, with the promise that those who bought it for a few dollars now would get all future updates at no additional cost. There was also the promise that the price would go up in the future as more features were added, and the finished game would cost even more. Buy it now, in other words, because the price will only get higher.

It's a format we now take for granted: buying an incomplete game at a discount in the hopes it'll someday be finished and we'll have saved a few bucks—and maybe we'll also get to suggest new features that will end up in the game. It often doesn't work out that way, but it's easy to see why Minecraft's sales model became so popular for both developers and customers. The initial trickle of sales quickly became a flood, to the point where Persson's account was frozen by PayPal, which became suspicious of the massive influx of money. By 2011 Minecraft had sold a million copies. By 2013, 10 million.

In 2014 Persson sold Minecraft to Microsoft, and it's now the best-selling video game of all time, with sales somewhere around 180 million copies on just about every platform available. Minecraft's design, its procedural open worlds, and its deep crafting systems have been heavily influential to scores of other games, but it also set the stage for a decade of Early Access, paid alphas, crowdfunding, and two distinct promises that aren't always kept—for customers, you can buy in early, save money, and influence the final project, and for devs, you can fund your game's development by selling it before it's done. —Christopher Livingston, Staff Writer

League of Legends (2009)

League of Legends isn't an esport, it's the esport. When Riot Games first started hosting world championships and investing in its competitive scene, it was also inadvertently building the template that nearly every other competitive game would follow—but none would ever fully replicate. Though esports tournaments had happened before, Riot turned League of Legends into a spectacle, investing heavily in stage productions and musical performances that turned what would've been just another nerd tournament into a mind-bending multidimensional performance. In 2017, for example, Riot used augmented reality tech to make it look like a giant dragon stormed the main stage during a musical performance. Or just this year, when musicians performed alongside 3D hologram characters. It's bonkers.

But that's just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how League has shaped esports. The entire infrastructure of esports as a business was pioneered by Riot. When it created the NA and EU League Championship Series, it turned esports into a year-round event much like any other sport—in turn also legitimizing competitive gaming as a full-time job. And that shift didn't just enable players to go full time, it also created hundreds of adjacent, legitimate jobs in commentating, esports journalism, and production. With Riot's help, esports went from being a hobby to a career.

That still doesn't cover all the ways League of Legends has influenced the games industry, either. Riot was one of the first companies to adopt an aggressive update schedule that continually added to and rebalanced the game, creating a breathing meta that kept players engaged for thousands upon thousands of hours. It also was a major contributor to the growth of Twitch in its earlier years and remains one of its most-watched games, helping legitimize an entire industry of streamers. And though League of Legends isn't solely responsible for any one of these innovations, you'd be hard-pressed to find a game with a wider impact this past decade. —Steven Messner, Senior Reporter

Arma 2 (2009)

Arma 2 was the fertile Czech soil that produced two whole-cloth genres: survival and battle royale. It turns out that when you put high-fidelity voice, ballistics, and vehicle systems inside 225 km² of terrain, modders come up with all kinds of cool shit.

Despite a list of technical issues that took a new engine to work through, DayZ mod was groundbreaking for its sense of vulnerability, scale, and tendency to generate campfire stories. In 2012, "It was a shooter that you entered without a gun," a novel experience that lent no comforts or even a stated purpose, but that empowered players to form their own moral systems and roleplaying. Creator Dean Hall was inspired by the hardship he endured during a training exercise with the New Zealand military, when in the jungles of Brunei he lost 50 lbs and nearly died. The desperation of DayZ's wandering, scavenging, and unscripted interactions were carried forth by games like Rust, H1Z1, SCUM, ARK, and Hunt: Showdown.

A portion of what we play today is owed to Bohemia's dedication to making its game extraordinarily moddable. Not long after DayZ, no-name modder PlayerUnknown entered the 2014 Make Arma Not War contest, an official talent search meant in part to find the next DayZ. PlayerUnknown won €30,000—second place—for a spin-off of his novel Battle Royale mod, a format that took Arma's sandbox systems and focused them into an ever-shrinking deathmatch. —Evan Lahti, Global Editor-in-Chief

Farmville (2009)

Farmville released just before the start of the decade and peaked with an insane 80-something-million players in 2010. The early years of the 2010s were dominated by fear that Zynga, with its overnight millions of dollars, and Facebook, with its massive influence, were the future of games. "Casual" was an insult aimed at these sorts of games and the people who played them; real games were "core" or "hardcore." Social network games like Farmville were lumped in with iPhone games to prove that videogames as we knew them were doomed.

Those fears were exaggerated, but they weren't exactly unfounded. The mechanics of free-to-play games have made their way into the biggest videogames in the world. It's commonplace to pay for in-game cosmetics or items or loot boxes or convenience, the real legacy of Farmville and other pioneering social games. You can pay money to get something quickly, instead of spending many hours playing a game to "earn" it. Farmville wasn't the very first game to be designed around exploiting its players' compulsive habits for profit, but it helped write the book for the decade of F2P games that followed.

Its influence wasn't entirely negative, however. Those years of angst over casual games now seem childish, and the PC is home to a more vibrant and diverse range of games than we could've imagined a decade ago. The same goes for the people who play games. Hidden object hunts and Doom and Stardew Valley are all shelved together on Steam, and they're all bringing someone joy. Maybe even someone who got into gaming because of Farmville. —Wesley Fenlon, Features Editor

Final Fantasy XIV (2010)

Final Fantasy 14 was not the first game to launch in an absolutely disastrous state, but it was the first time a major studio admitted fault and then sunk considerable resources and time into rectifying its mistakes. In 2010, the original FF14 was intended to be a kind of spiritual successor to the aging Final Fantasy 11 MMO, but it ended up being a mishmash of unfun ideas and incomprehensible designs. People hated it. The wisdom of that era would've suggested Square Enix sweep it under the rug and never look back, but instead it did the exact opposite and set an industry-wide precedent in the process.

Over the course of nearly two years and with a visionary new director at the helm, Square Enix rebuilt FF14 from the ground up—an almost entirely different game but still set in the same world. It was a historic display of commitment and an enormous gamble that, ultimately, paid off. FF14 is now easily the best MMO available.

But FF14's real legacy is leading a much wider trend of increasingly common comeback stories that speaks to our increasingly complicated relationship with games as both products and experiences. Shigeru Miyamoto once said that "a delayed game is eventually good, but a rushed game is forever bad." But Final Fantasy 14 proves that isn't true. Games have always come in all shapes and sizes, but FF14 is a testament to how that shape and size is transient. —Steven Messner, Senior Reporter

Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood (2010)

The way Ubisoft's various open world games have grown and changed over the past decade has been interesting to witness. Series like Assassin's Creed, Far Cry, The Division, Watch Dogs—they all interbreed and learn from each other. If one game develops a new feature (climbing towers to discover new areas of the map in Assassin's Creed, for instance), it's not unusual to see some form of that feature appear in a game from another series (you climb similar towers in Far Cry 4 and Watch Dogs). Sometimes those features disappear, too, when players get absolutely sick of them (which is why you don't climb towers in Far Cry 5 or Watch Dogs 2, thank god). It's video game cross-pollination, and it's not limited only to Ubisoft. Plenty of other games have learned lessons from Ubisoft's endless refining of its open world games.

There's a sweet spot in the creation of a world, a line between a setting that feels too barren to make exploration or side-tracking rewarding and one that feels overstuffed with pointless, grinding activities. Ubisoft has veered back and forth over this line several times this decade, often cramming in far too much—like in Far Cry 4, with so many gatherable resources and crazed animals and hostile NPCs and other distractions—that the sheer amount of icons on the map feels exhausting.

Assassin's Creed Brotherhood had the balance just right, a vibrant, interesting world with just enough engaging side-quests and distractions but stopping short of feeling like an oppressive to-do list. You couldn't go hog-wild without gaining notoriety, meaning guards would begin recognizing you more easily, giving your actions consequences. You also had an impact on the world—taking down a tower and killing its commander revitalized the area, letting you renovate shops that would benefit you with new items and upgrades. A novel feature that let you hire, train, and dispense your own collection of assassins provided a feeling that things were happening even if you weren't there to witness them. It's easy to see the influence of Brotherhood in other open world games—and it's obvious when Ubisoft doesn't carry its lessons forward in its own. —Christopher Livingston, Staff Writer

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011)

How do you make a singleplayer game that thousands of people will still play on a daily basis almost 10 years after its release? Make it moddable. Does anyone talk about 2016's Doom these days? No, because what is there to talk about after you've finished it? But 1993's Doom is still making news regularly because it's still being modded after 26 years, and I guarantee people will still be modding Skyrim for another decade, too. No need for years of DLC, no season passes required. Just give passionate and creative players the tools and freedom they need to craft their own fun.

It helps that even vanilla Skyrim is all about freedom and creating your own adventures. Its big open world is packed with quests, stories, characters, and lore, but once the tutorial is completed there's very little pushing you in any one particular direction. You can go where you want and be who you want—you're the Dragonborn, sure, but you can play for hundreds of hours without ever kicking off the questline that introduces dragons into the world.

That same spirit of freedom applies to Skyrim's extreme moddability. Nexus Mods, a Skyrim modding hub, reports over 1.7 billion downloads of mod files, and more than 60,000 different mods. That keeps the aging RPG fresh with new adventures, companions, locations, weapons, spells, and complete overhauls of game systems long after you've completed the vanilla experience. Just this week alone, 56 new Skyrim mods appeared on Nexus Mods for the nine-year-old RPG. There's an entire lifetime of new experiences for players to discover and a way for Skyrim to endure long after Bethesda has moved on to other games. —Christopher Livingston, Staff Writer

Mass Effect 3 (2012)

Fallout 3's ending was so disliked Bethesda rewrote it in the Broken Steel DLC, grafting on a new epilogue and a better climax. But if you didn't buy that DLC you still have the ending where your companions refuse to help because the finale was clearly plotted before they were added.

Mass Effect 3 was different. Its original ending was honestly no worse than Fallout 3's, but unlike Bethesda, BioWare did not wait seven months and two DLCs to address fan complaints. It was 16 days after its release when BioWare CEO Ray Muzyka wrote that "out of respect to our fans, we need to accept the criticism and feedback with humility" and three months later the Extended Cut was out.

The fan rage at Mass Effect 3's ending was effective because it was organized. A campaign called Retake Mass Effect that involved donating money to Child's Play to get BioWare's attention raised $80,000, there was a flood of YouTube videos breaking down different reasons why the ending was bad, conspiracy theories about the "Indoctrination ending," and thanks to social media, the conversation fed itself. If there's one thing YouTube, Twitter, and Reddit all agree on it's that anger is the best fuel for engagement. Legitimate complaints that the ending was a bit weak were buried under the kind of hyperbolic rage that goes viral.

It provided a playbook for fan discontent that's reared up again and again, from the reaction to No Man's Sky to the Sonic the Hedgehog movie. After years of trying to explain that the stereotype of "entitled gamers" is a myth the 2010s came along to say that no, actually some people are pretty entitled and will campaign to have an ArenaNet employee fired because she was rude to a Guild Wars 2 fan on Twitter. Mass Effect 3 was just the first canary in this particular coal mine. —Jody Macgregor, Weekend Editor

CS:GO (2012)

On the last day of PAX Prime 2011, I took 20 minutes to wander over to a small, half-populated booth on the show floor and check out Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. CS:GO wasn't a big priority for PC Gamer's coverage that year—a lot of the game's development had been outsourced to Hidden Path, creators of a tower defense game. CS:GO was just a better-looking CS:Source, right?

Actually, it was mostly a port. With Microsoft and Sony's consoles getting long in the tooth, Valve didn't want to miss the business opportunity to bring one of its franchises to the Xbox and PlayStation. Sure, they'd put Global Offensive on PC too, but the focus was mostly on porting it, evidenced by the fact that CS:GO was only playable on the Xbox 360 at PAX. Valve touted cross-platform play alongside visual makeovers of beloved maps like de_dust2 and cs_office.

This afterthought release eventually became the biggest competitive FPS of the decade.

What inspired Valve to transform CS:GO from a console port into a flagship were the lessons learned over Team Fortress 2's development. In 2013, one year after CS:GO's release, Valve introduced cosmetic weapon skins. But where TF2 merely popularized the crate-and-key system, CS:GO brought new layers of economic insanity to it. Within the player-run Steam Market, custom AWPs, M4s, and Deagles—with 13 years of meaning soaked into their metal—became massive status symbols, with towering, real-dollar price tags. The dullest pure-white MP7 skin can still fetch hundreds of dollars, simply because it's somewhat rare.

Best CS:GO skins: FPS style

CS:GO ranks: How they work

How to surf in CS:GO: Tips and servers

Before weapon skins arrived, the populations of CS '99, CS '04, and CS '12 were roughly equal. But skins drew CS' most entrenched fans out of their favorite edition, and were the carrot that Global Offensive needed to absorb its older siblings. Not only could you earn limited-edition skins by watching big CS:GO tournaments, but third-party sites like CSGO Lounge let tens of thousands of players bet on esports matches with their Steam inventories. Two YouTubers exploited the black market that had emerged around CS:GO, creating their own gambling website and marketing it to their audiences on YouTube and social media without disclosing their co-ownership, a scam that eventually led to new FCC guidelines governing influencers.

CS:GO's rise coincided with Twitch's own, and as Valve discovered that it had a highly watchable, exciting spectator FPS, the studio began putting up prize money for major tournaments. The most popular pros showcased their gun and knife fashion like sneakers on LeBron. Eventually Valve produced team-specific skins and digital player signature stickers, with much of the proceeds going to those pros. With match spectating built directly into the game client itself, Valve had created a perfectly contained loop of self-promotion.

As Finnish pro player Tomi "lurppis" Kovanen told me in 2015, “Without the item economy Counter-Strike would be smaller. … There would be less money [in esports], no Valve-sponsored majors, and no one-million-viewer grand finals. In hindsight, the addition of the skins has been the most important development in CS:GO's history, bar none.”

The broader outcome of all of this is the way that CS:GO's sky-high skill ceiling became a template for FPSes that have followed, from Rainbow Six Siege and Apex Legends to Riot's still-unnamed shooter. As CS:GO ballooned in popularity, it put pressure on Valve to raise the technical quality for Counter-Strike's decade-plus fans. CS:GO embedded once-grognardy terminology like tick rate and peeker's advantage in the consciousness of millions of FPS players. And the game's scale of CS:GO allowed Valve to pursue a new machine learning technique to combat cheaters, VACnet, an approach since duplicated in other anticheat services. —Evan Lahti, Global Editor-in-Chief

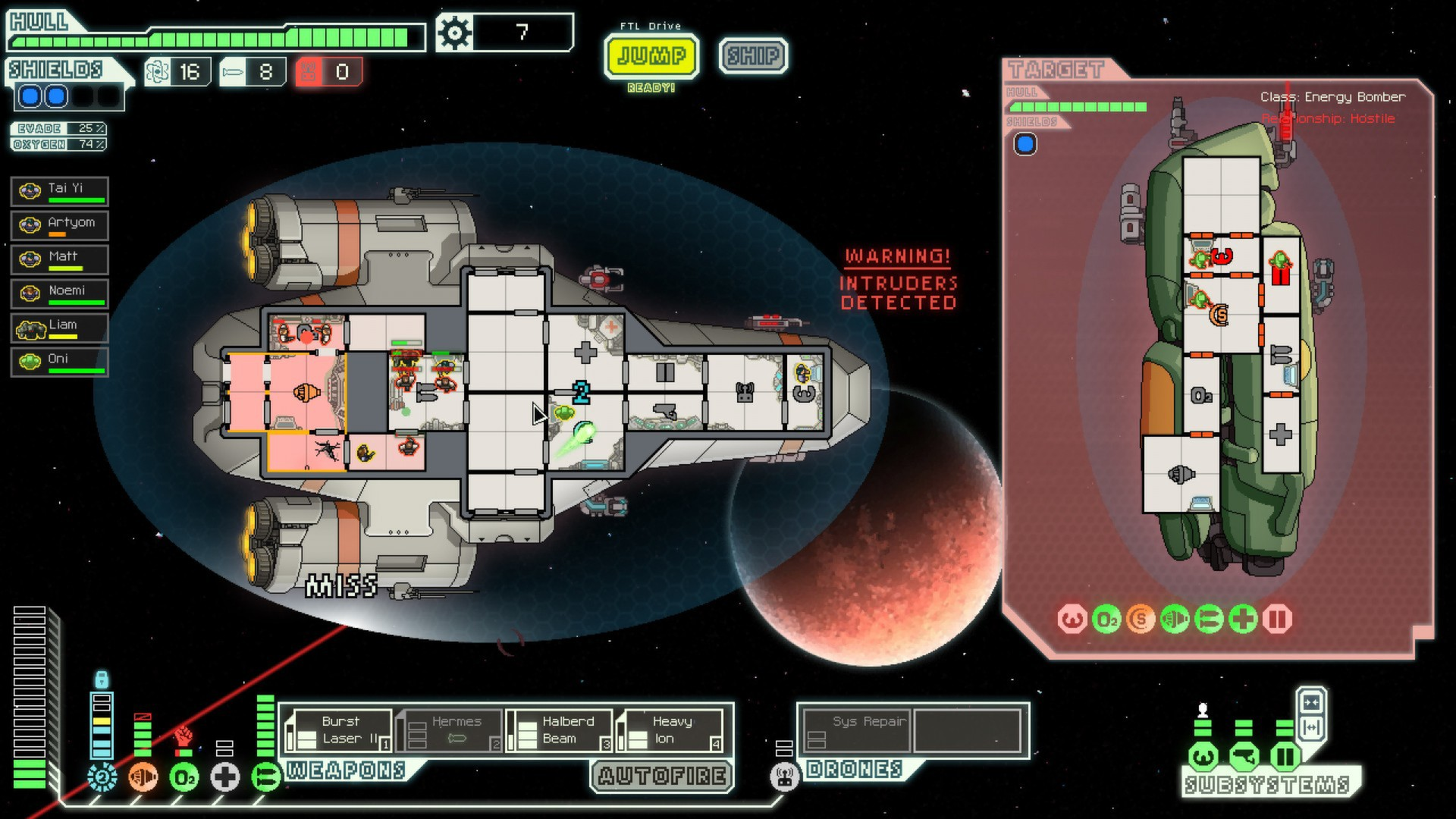

FTL: Faster Than Light (2012)

Though it looks strangely humble now, FTL was a pioneering game in all sorts of ways. Years before the likes of Broken Age and Pillars of Eternity, it was one of the first titles to be successfully funded through Kickstarter, earning over $200,000 dollars from eager fans – 20 times its initial $10,000 goal. Created by a tiny two-man team, its huge success and popularity helped pave the way for countless indie games to come over the course of the decade, demonstrating beyond doubt that clever design and creativity could allow tiny studios to rival the endless resources of their triple-A competitors.

Casting you as the captain of a rebel starship on a desperate suicide mission, it challenged you to manage your vessel’s crew and systems during Star Trek-like battles as you progressed through procedurally-generated galaxies. The combination of inventive strategy with the design principles of the then-nascent roguelike genre proved instantly compelling. And in bringing that formula firmly into the mainstream, it laid the foundations for countless hits to come, including recent gems such as Slay the Spire, Darkest Dungeon, and the developer’s own Into the Breach. —Robin Valentine, Managing Editor

Crusader Kings 2 (2012)

Crusader Kings 2 is a singular sandbox that's unlike any other strategy game, though it's not obvious at a glance. The seemingly infinite menus and lists and popups that you think will make you glaze over are really windows into the greatest medieval soap opera, filling the last eight years with countless absurd anecdotes about murder plots, sexy scandals and occasionally black magic. This obtuse historical grand strategy game unexpectedly became a gateway drug, with all the story possibilities making the dense strategy easier to digest. A lot of people go their first taste trying to unite Ireland, once the recommended starting place for newcomers.

Previously, grand strategy had been great at conjuring up interesting scenarios, but stories not so much. They were focused on warfare and economics and all these abstract things, but Crusader Kings elevated the much more unpredictable and stimulating people (and sometimes animals) that lived in these competing kingdoms. If you enjoyed torturing people in The Sims or watching the drama unfold in Game of Thrones, suddenly there was a strategy game perfect for you—social, human and a bit silly.

It's also stuck around throughout the decade thanks to a cavalcade of DLC and free updates that have overhauled the game several times over, flinging in more religions, cultures, vikings and just as many new systems. So many live service games have sprouted up, but Paradox Development Studio managed to do a much better job of creating a living game without a lot of the accompanying nonsense. The amount of paid DLC has ruffled some feathers, but I can think of few other games that have been given this kind of support, especially when so many of the significant additions have been free. And now the base game, which has benefited from eight years of continued development, is free, so there's nothing stopping you from usurping some thrones. —Fraser Brown, News Editor

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Arma 2. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging. Evan also leads production of the PC Gaming Show, the annual E3 showcase event dedicated to PC gaming.

- Christopher LivingstonSenior Editor

- Wes FenlonSenior Editor

- Jody MacgregorWeekend/AU Editor

- Steven Messner