The most ambitious PC games

These games strained against the technical and design limitations of PC gaming and did something that had never been done before.

Every game is ambitious. It’s not easy to turn a beautiful idea into a finished, playable game—as developers have said time and again, sometimes it feels almost impossible. As miraculous as finishing any game might be, not all games are created equal. Some stretch the boundaries of technology to their breaking point. Others take a leap into the unknown with new design schools, often so effectively that years later, it’s hard to remember them ever having to be invented.

Think, for example, of Monkey Island’s “Three Trials” structure, as used by almost every adventure afterwards. Or its sequel’s “Four Map Pieces”, as later picked up by BioWare. And sometimes, both art and science combine to push the envelope and we get something truly, impossibly special. Here are our picks for the top 20—ignoring the very early games that had to prove computers could handle gaming at all.

For more on some of the most monumental games ever to grace the PC, check out our feature on the most important PC games.

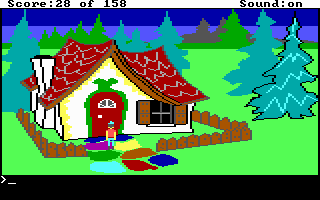

King's Quest (1983)

For the longest time, adventure games were where people looked to see the latest innovations. King’s Quest set that bar early on, jumping from simple text and pictures to 3D environments, huge worlds, and a fairytale land of mystery to both wander and wonder at. Admittedly, the last part was helped by some dreadful puzzles. King’s Quest was originally commissioned by IBM as the showpiece for its long-forgotten PCJr system, but the series would go on to demonstrate just about every major technological advancement for the mainstream: ADLIB sound, VGA graphics, full speech, and high resolution. 3D didn’t work out so well, but until that point, King’s Quest was where many players went to get their glimpse of the ever-advancing future.

Commander Keen (1990)

If you want to experience pure hell, try the average 80s PC platform game. Long before making Doom, the team that would be id Software wanted to prove that the PC could handle experiences that played as smoothly as dedicated consoles. Commander Keen wasn’t just a fluid experience by the standards of the time, but a fast one, with pogo-jumping, shooting and big levels to explore. Looking back, it’s hard to appreciate what a development it was, but we’re talking an era where games like the original Duke Nukem (or Nukum—either way, the one who wore a pink suit and watched Oprah) were constantly being held up as the PC’s answer to Mario. Commander Keen didn’t qualify either, but it paved the way for many sequels and the formation of id itself.

A bit of bonus ambition: before making Keen, id tried to convince Nintendo to let it port Super Mario Bros. 3 to the PC by building a working demo (in their off hours in a single week, no less). Nintendo said no thanks, but you can see footage of the demo here.

Maniac Mansion (1987)

If you made a game like Maniac Mansion right now, people would still rightly call it ambitious. A choice of seven characters, each with their own skills. A non-linear adventure with five different endings depending on choices and characters. Real time elements, like ringing the doorbell and having a character come downstairs to check on it. Puzzles involving multiple characters in different rooms of the house… or simply the option to do things like put a kid in an empty swimming pool and then fill it back up. And on top of all of this, Maniac Mansion brought the world the SCUMM system (Script Creation Utility For Maniac Mansion) that would define about half the adventure game market for the next decade. All of this, in 1987. Few adventures have ever done so much.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Ultima Underworld (1993)

Like most of the games on this list, Ultima Underworld is a fusion between ambitious technology and ambitious design—the design side specifically being to take one single dungeon and try to breathe life into it. To add nuance to its different races, there to be talked to instead of just beaten up. The Stygian Abyss wasn’t just a battlefield. It was a fallen community. A place to live in. The experience of being thrown into a dungeon and just expected to survive.

What really sold it though, if your PC could run it, was the technology. Before even Wolfenstein 3D, Ultima Underworld offered a full 3D environment complete with slopes, lighting effects and more, in a bit of technology that could only have been more impressive if… well, the viewing window had been a bit bigger. Underworld 2 greatly increased the scope of the game, visiting other worlds and making it a bit easier to see, but what the first one managed remains a technological victory worthy of any heroic age.