The 'micro-RPGs' offering new perspectives on the genre's overstuffed epics

RPGs don't need to take hundreds of hours to make their point.

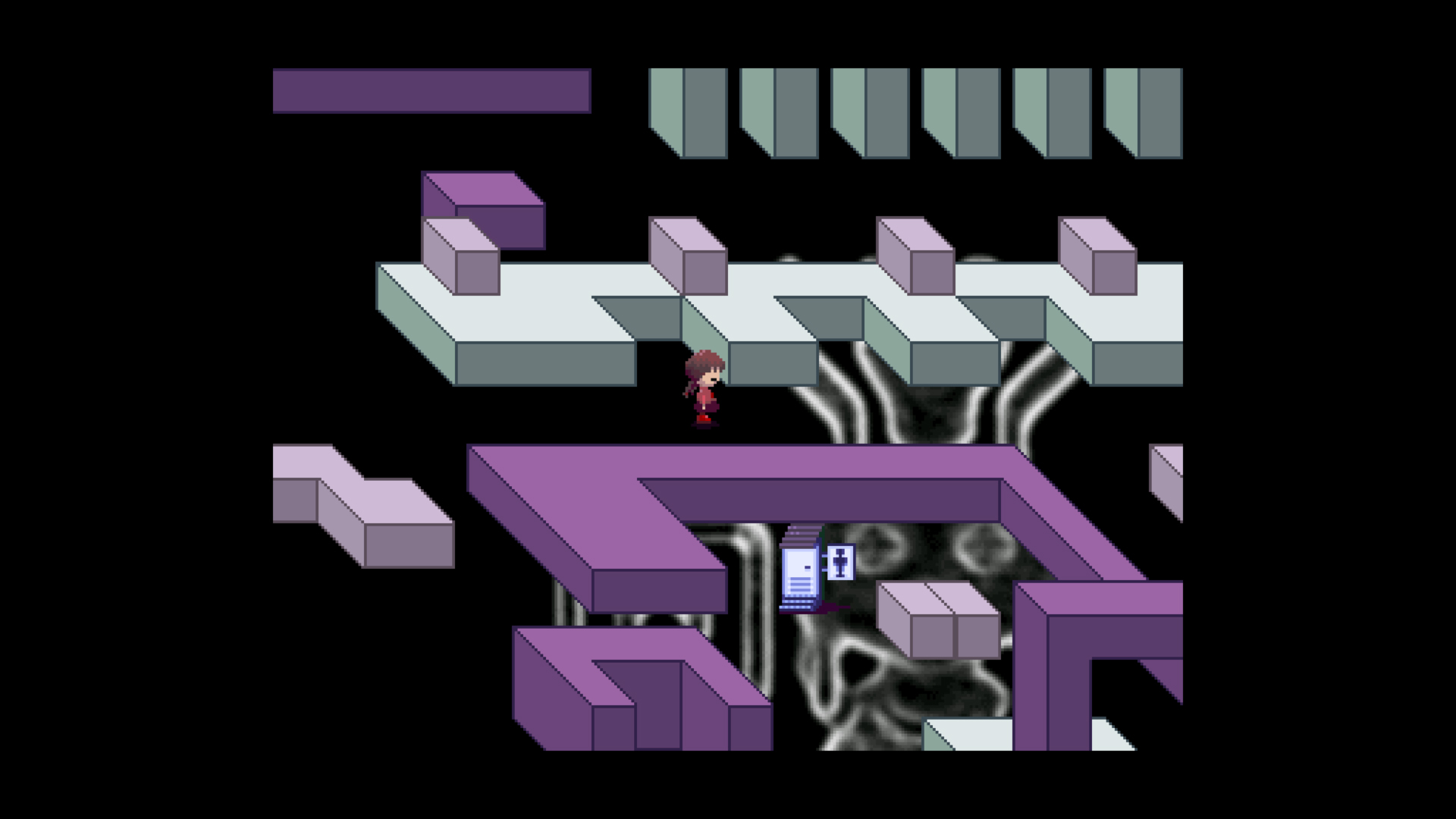

In what crumbling, dragon-leather tome was it written that role-playing games have to be so incredibly long? It's certainly not a convention that rings true for Sraëka Lillian, whose RPG Maker-based 'OI' games clock in at a few hours apiece. Each is a focused exploration of one of "a thousand little questions" an RPG developer must answer—Atom OI, for example, is an interrogation of the nuances of status effects. "My points of obsession are these fundamentals of RPG design, right?" Sraëka explains. "And I don't need to make a big game to explore those."

Once you're done with the OI games you could move onto jetstorm4's Fallen Star, or John Thyer's Facets—two wordier yet equally brisk productions that are pitched as the climax of longer, untold fantasy stories. "Like, you get that there's a 20 hour version of this," says Thyer, "but we're cutting straight to the part you care the most about." Or if you want something a touch more esoteric—Hylics, Mason Lindroth's visually overpowering but concise claymation escapade. Or for a splash of romance, Get In The Car, Loser, the hectic lesbian roadtrip RPG from Ladykiller In A Bind developer Christine Love, which tells much of its story in the backseat of a speeding pink convertible. Or for something at once comedic and darker, Slimes from scitydreamer, in which you play an asshole adventurer eradicating a single dungeon's worth of Dragon Quest's least-threatening critters.

That's just a small sample of the genre—'micro' or 'capsule' RPGs, ranging from surgical poetic experiments crafted with free tools such as RPG Maker or Game Maker, to slightly bulkier commercial indies that sometimes play like ruthlessly efficient fan edits of blockbuster RPGs. Micro-RPGs are music to the ears of genre fans who no longer have time for the kinds of games they binge-played as kids, but even if you're a diehard Dragon Age player with weeks to spare, these games are worthwhile for how they concentrate and reveal things about the behemoths they riff on.

It's hard to say when RPGs became associated with gruelling length, partly because 'RPG' has become an enormously elastic term, stretching to everything from Elden Ring through Borderlands to Persona 4 and Skyrim. The primary checks on playlength are practical factors: the size of your team and budget, production timeframes, and having access to the right tools. But Bill Steirnberg—one half of Cosmic Star Heroine developer Zeboyd Games—also dates the expectation of a mammoth hour count to the original PlayStation era and the rise of FMV-led RPGs like Final Fantasy VII. "It's funny how the context changes. So like, Chrono Trigger is a classic, everyone loves it, and it's something like 20 hours long, even if you don't know exactly what you're doing. But somewhere in the late 16-bit, 32-bit era, there came this notion that 40 hours was the expectation. And then as the PS2, PS3 rolled on, that became 60 hours. And now 90 hours long is normal."

This is especially the case, of course, with premium- priced blockbuster RPGs. "You can tell a great story in two or three or four or five or six hours, and I wish there was more of that," Stiernberg goes on. "But understandably, a big studio is not going to take that risk—they're not going to pour a large or even a medium budget into an RPG that's four hours long. And that's kind of where small studios like ours come in."

Too big to fail

John Thyer suggests that players in North America and Europe have fallen out of love with shortform art in general, linking the bloating of RPG playtimes to the rise of 'extended' narrative universes across games, film, and TV. "I think that it's hard sometimes to just sit down with a smaller work—I feel like that translates to how the Marvel Cinematic Universe is really popular right now. People like following one big epic story over a long period of time. And I think that it can be hard for people to accept a smaller thing, a one-and-done thing that tells a complete, satisfying story, because it doesn't feed that nerd brain quite in the same way." Thyer also points to the broader 'fetishisation' of complexity in art as a potential catalyst for exhausting playlengths. There are obvious connections with service-based monetisation, with publishers like Square Enix transforming their already-gargantuan fairytale settings into persistent revenue platforms that are designed to hold your attention indefinitely.

It can be hard for people to accept a smaller thing, a one-and-done thing that tells a complete, satisfying story.

John Thyer

Some shortform RPGs play like refreshing, puzzler- style deconstructions of systems from those exhaustive big studio projects. Sraëka's wonderful Cataphract OI, for instance, is a meditation on time inside and outside combat. Four adventurers invade a fortress to break a time loop – a premise that feeds into battles whose participants are effectively suspended outside time and so invulnerable unless forced into 'the fray'. The project began life as Sraëka tinkering aimlessly with a novel movement system—enter a room, and your party wanders through and fans out in a crisp kind of characterisation. "I wound up dropping off for a year coming back and saying, OK, I have some pieces here, I want to make something out of them. And so it was really what can I do with the pieces I've already haphazardly slapped down on the board, rather than a thoroughly, intentionally probing experiment."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The personal touch

Get In The Car, Loser, meanwhile, condenses its playtime by focusing on cast interactions. Inspired by Valkyrie Profile and Final Fantasy XIII—a game whose opening half is one drawn-out getaway sequence—it leans into the fact that party-member sidestories are often more involving than the overarching plot. "It's got four characters, four bosses, four areas, and each chapter revolves around a single character's concerns," Love says, adding that she hopes "the main reason to keep playing is to hang out with them more". The character focus "meant we could de-emphasise certain things, like complicated plot twists or map exploration, in favour of the feeling of 'you learn a lot about people when you're on an adventure in a crowded car with them'". Having the whole yarn play out on the road also gave Love's team tighter control over the alternation between dialogue and battling.

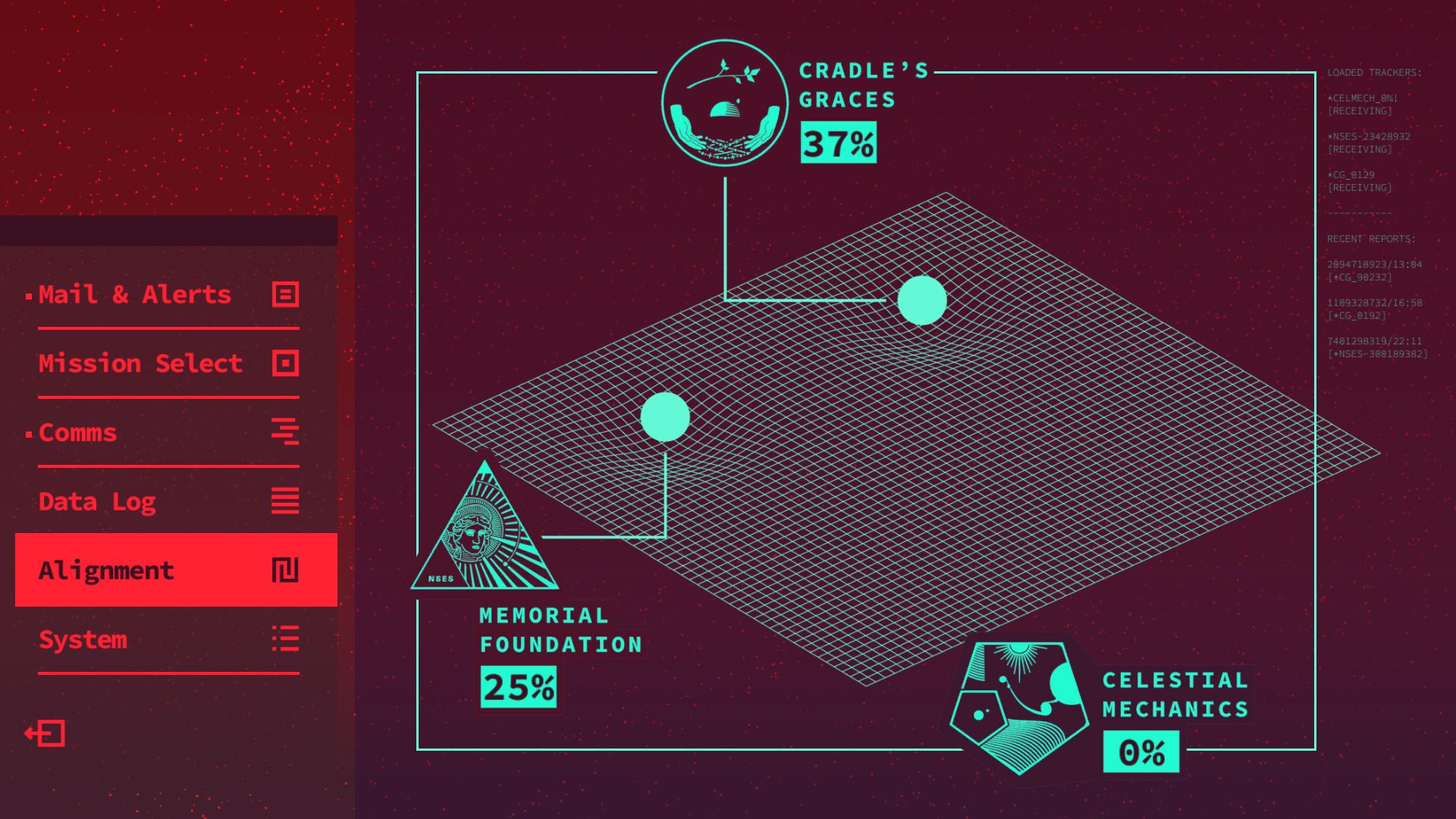

GITCL often relies on comedy to stop things dragging, "If there was ever a moment that felt a little too boring to me, I could just punch it up with jokes," Love says. Many micro-RPGs are comedies or parodies – two formative examples are Magic Wand from thecatamites and Toby Fox's Undertale. Zeboyd, especially, has profited from developing RPGs with tongue in cheek. "[When] we made Cthulhu Saves The World, game comedy was pretty uncommon," Stiernberg says. "There was this gap in the market. So we wanted to appeal and just be entertaining with the story that way, since we knew we weren't making some huge 40-hour epic." Cosmic Star Heroine, meanwhile, is a more earnest spoof of spy cinema – another flavour of story that puts an emphasis on snappiness. "Instead of going with a Mass Effect-esque space drama, we wanted to do a more James Bond story where it's fast-paced, you're undercover half the time—there's a whole scenario where you go to a dinner party in disguise."

Which is not to say that shortform RPGs can't explore more sombre themes. Thyer's Facets, for instance, began life as a homage to boss dungeons in early Final Fantasy, but evolved into a difficult and very personal narrative about a group of dream-diving inquisitor-type figures rewriting somebody's personality. FF aside, Thyer took inspiration from RPG Maker projects OFF, Space Funeral, and in particular the legendary Yume Nikki—a shifting strata of dreamworlds with no combat or levelling. "It represents these really raw, ugly feelings almost purely through RPG map design, and that's fascinating to me. So I was like, what if you're exploring a brain that's explicitly a psychological space, what if these bosses are pieces of that personality... I was in kind of a dark space, making the game – it was the end of my marriage, I was getting divorced. And my brain went to conversion therapy and telling this really tragic, ugly, sad story."

While clearly set in a larger narrative universe, Facets avoids undue exposition about, say, the means of invading minds. "I think having thought that stuff through helped the endgame land better because there was a logic, and if there's a logic to the creator, that usually comes across to the player," Thyer says. "I just don't waste their time actually explaining it, because I don't think it matters to the feelings I want to get across."

Tolkien points

Many bigger RPGs embrace exposition because they are steeped in the legacy of certain ponderous fantasy or science-fiction books, such as The Lord of the Rings, but as Zeboyd's other half Robert Boyd points out, fantasy and sci-fi needn't be colossal exercises in world-building or stretching a plot across continents and generations. "If you look at the horror genre, Resident Evil 4 is a good 20-25 hours long. But you can also have a very succinct 90-minute horror experience that tells a good story. You can have a Twilight Zone episode, that's a half an hour that tells a complete story, or a Junji Ito comic strip that you could get through in ten minutes. It leaves an impact if it's done well. So I think the idea that fantasy or sci-fi RPGs have to be really long is flawed. I think there's room for the equivalent of a short story."

The idea that fantasy or sci-fi RPGs have to be really long is flawed. I think there's room for the equivalent of a short story.

Robert Boyd

Grandiose narratives in RPGs are also justified with reference to levelling systems—the idea is that you'll have more of an emotional connection with characters after spending dozens of hours tuning their stats. But do progression systems really need a 20+ hour runtime to have such an impact? "I feel like you can have progression levelling systems even in a short game," observes Boyd. "Maybe you want to simplify them so much that you're not poring over Path of Exile-style massive matrices, trying to min-max everything, but there's no reason why you can't have a five-hour game that has a strong progression system. We see that with games like Super Metroid—you can beat the whole thing in four or five hours, but you're constantly gaining new abilities and more power as you progress."

Stiernberg notes that how many different abilities, spells, perks and so on you pack into a progression system is less important than how you pace them. He stresses the importance of "a reasonable learning curve that doesn't just throw you in the deep end—although that there's some merit to that, being thrown into the deep end can be really interesting—but just being able to learn and apply it and towards the end, being able to really dig into the strategies".

Well-wrought shorter RPGs such as Zeboyd's own Cosmic Star Heroine demonstrate that quick progression arcs can be satisfying, but as Love cautions, they also show that RPGs do generally need more time to teach their intricacies than other genres. "Especially if you're introducing unfamiliar mechanics to people who are otherwise very familiar with genre conventions, it's really important to not rush through things, or the player will just say, 'Oh, yeah, I've played RPGs before, I know this!' and then get frustrated when it causes them trouble later in the game, so the desire to not bore the player with dragging out introductions, and the desire to just 'get to the good part' can be at odds."

Experience not required

A conspicuous reliance on grinding aside, Sraëka argues that sluggish endgames are the most obvious symptom of RPG bloat. "Part of what keeps the friction of fighting battles down early on is novelty. And it's common to not introduce a whole lot in the back half, though there are RPGs that do mix things up that I think are really interesting. The 7th Saga [for SNES] gives you these items you can use over and over that can restore your HP in battle or give you powerful buffs that are almost necessary for survival. You accumulate these through the middle three fifths of the game, become very dependent on them, and then it takes them all away for the last act. You have to learn how to fight all over again."

Sraëka feels that RPGs should "push back" on players more towards the finish, though they acknowledge that balancing a character's capabilities at every point in an RPG is a huge labour. The OI games don't feature XP or levelling: it's more like meeting with the party at a critical point in their adventures. "It is a lot simpler to balance these things as a single person if you don't have to worry about all these variables changing. It's a wonder to me that anyone—especially solo developers—has ever completed a long RPG where the numbers are going up the whole time, and you have to account for them at each stage."

While they hold out hope of working on a larger RPG project some day, Sraëka has plenty of "unfinished business" with RPG Maker and doesn't regard the OI games as "stepping stones" to a grander opportunity. "A lot of my work comes from the feeling of, 'I'm really restless right now, I want to make something and I don't want to spend forever on it.'"

Thyer, similarly, doesn't see Facets as the prelude to a larger, more commercial project, not least because he values peace of mind over professional prestige. "I'm not trying to iterate on one thing and get really good at making RPGs and then spend five years making a 20-hour long RPG for Steam. I've just seen a ton of people get burned out taking that approach. I am more interested in doing literally whatever seems fun for me in the moment." Thyer also points out that the value of shortform games at large is the community they create, where people release quickfire experiments in response to each other's work. "I want to cultivate spaces where my friends can feel comfortable and encouraged to be just recklessly creative."

You could argue that RPGs tend to be gargantuan not because their creators associate time investment with enjoyment, but because they make a point of housing many different experiences, from wonky minigames through scenarios such as puzzle-dungeons to the systems that make up battle. Rather than 'epics', it's perhaps healthier to frame them as something akin to Thyer's hopes for the shortform gaming scene—a bustling collection of experiments, thrown together in the course of exploring a world. Micro-RPGs might take issue with the legwork involved, but they're not at odds with this ethos. They just give some of those flourishes a little more room to shine.