The making of What Remains of Edith Finch

How a bit of fishy business inspired Giant Sparrow’s sublime anthology.

The authority on videogame art, design and play, Edge is the must-have companion for game industry professionals, aspiring game-makers and super-committed hobbyists. You can subscribe to both the print or digital editions here. Edge 320 features Shadow of the Tomb Raider on the cover, and it's available now.

Welcome to the third guest article from Edge on PC Gamer, where we'll occasionally feature PC gaming-based articles from the long-running magazine's recent history. This was originally published in Edge 309 in July 2017, and is republished here with the Edge team's permission.

Like all good stories, it started with a shark in a tree. Giant Sparrow had begun developing its debut, The Unfinished Swan, with nothing more than what writer/director Ian Dallas describes as “an abstract but describable goal”. For that game, Dallas hoped to create a sense of awe and wonder; this time he was hoping to evoke “the sublime horror of nature”. The process had worked once, so Dallas and his team were emboldened to try a similar approach for its successor, but it wasn’t until three or four months into development that the image of a shark in a forest, falling 30 or 40 feet to the ground, came into his head. Nature’s sublime horror suddenly had a comedic edge, and the story of young Molly Finch – the first of this familial anthology – gradually took shape.

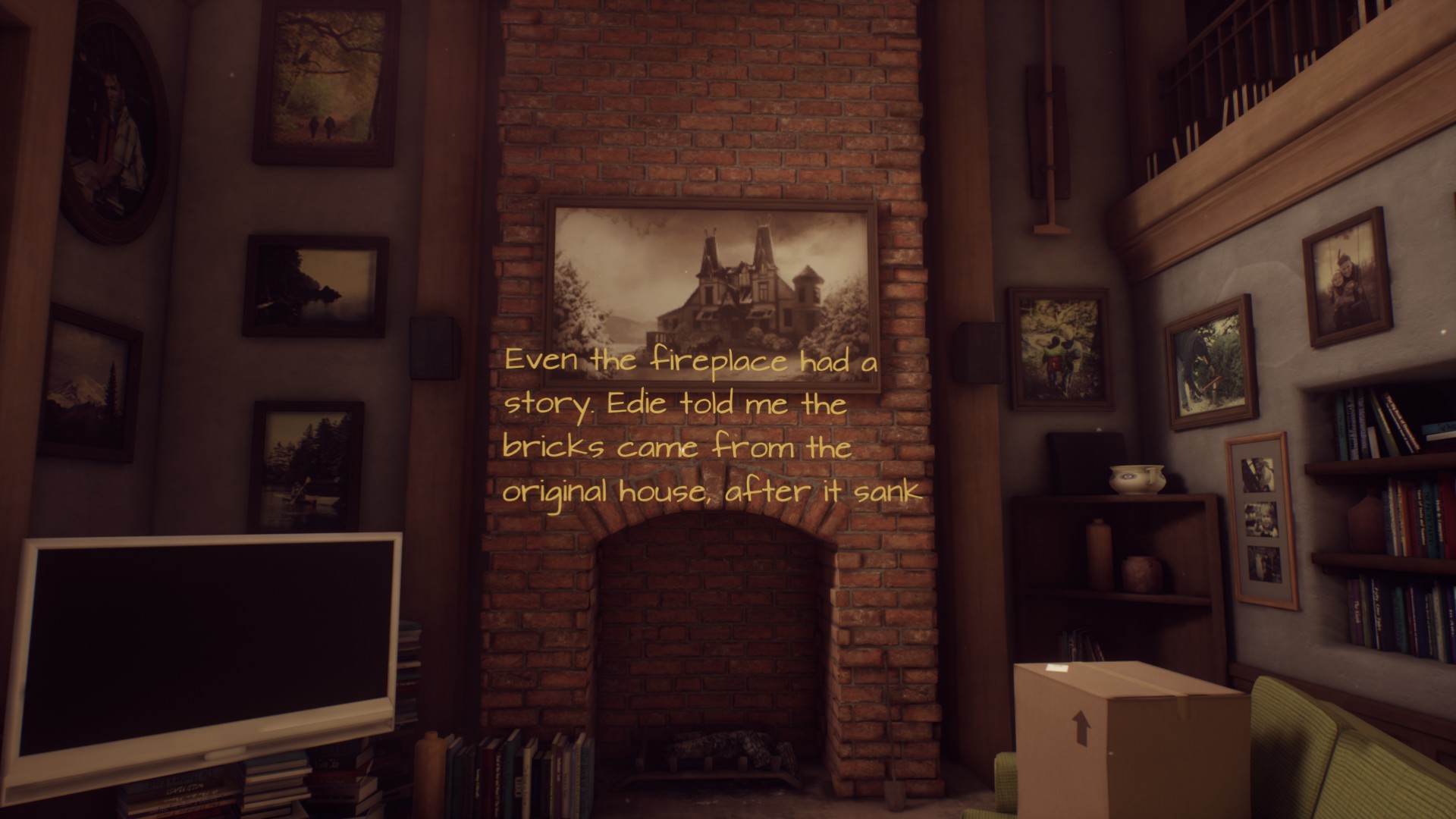

If the developer’s original plans had come to fruition, you might have encountered this fish out of water in its natural habitat. In its nascent form, What Remains Of Edith Finch was a scuba-diving simulator, inspired by Dallas’s memories of growing up in Washington state, and particularly “what it felt like looking at the ocean sloping away into the infinite darkness.” But in attempting to capture the sensations Dallas had experienced beneath the surface, Giant Sparrow hit its first major snag. “It’s really hard to tell a story while scuba diving,” he concedes. “Like, who is talking? What are the stakes? What’s the ticking clock? All these things that any story has to grapple with were hard to do.” Still, while the idea was abandoned, one early experimental prototype was a success. In considering how to tell a story in an undersea setting, Dallas wondered about inserting text into the world: a feature that not only remains in the finished game, but became crucial to the player being able to easily navigate the Finch mansion.

Ian Dallas, writer/director

Which of the stories went through the most changes?

Walter’s. Essentially, it was a riff on the Weeping Angels story from Doctor Who and also The Prisoner. There’s this guy trying to escape this strange world of 1950s Americana, and he walks around with a flashlight, and when he turns around this crowd of people with pitchforks gets a little closer. Then there’s a gradual reveal that you’re actually in a model train set, and this giant hand comes down periodically to move things around. Walter picks up this little person who had tried to escape, and then realises that he himself has to escape and then goes out the tunnel [as in the finished game]. The version we shipped with was the last 5% of this absurd dream, and the whole can-opening part was a very late part of that process.

Were you consciously trying to avoid the audio-log approach to storytelling?

Yes and no. For me as a player, that’s just not what I think games do well. The part that’s interesting to me is: what does it feel like to be a giant tentacle? Or what does it feel like to be on a swing? And so from the early days, that’s where we spent all of our energy, just making these interactive prototypes, and the story didn’t come in until pretty late in development.

Unusually, you can spoil the reveal of Edith’s pregnancy by looking down.

I’m generally not a fan of bodies in firstperson games, particularly feet. But our tech artist Chelsea Hash held onto this dream of being able to show [the protagonist’s] body for so long, and then it was as easy to show it as

not. I do really like that it’s something players can discover on their own. Some players are really blown away by it, and some like Neil Druckmann [who is credited as a playtester] – he just looked down, I think it was in the kitchen, and he said, ‘Oh, I’m pregnant’.

And then he moved on (laughs).

It was only right that Molly’s flight of fancy should come first in the story chronology, Dallas tells us, since everything grew organically from it. That key line, spoken with childlike guilelessness (“and suddenly I was a shark”) now seems like a disarmingly candid acknowledgement of the game’s unlikely origins. “It’s an introduction to the player, just like it was an introduction to us as developers, into what this game is going to feel like,” Dallas says.

This ambitious, elaborate sequence, during which you first assume the form of a cat and an owl, and then later control a slithering tentacle belonging to some eldritch abomination, was originally conceived as the template for all that would follow. The studio invested months of programming time in developing technology to infinitely wrap terrain, so that nine tiles’ worth of forest could continually follow on from one another, endlessly rotating like the treads of a tank. “We ended up making this system where you didn’t have any walls, [so] you could keep going forever and the world would appear in front of you. And then we ended up never using that again,” he laughs. “That’s typical of the excess of Molly’s story, that exuberance early in development of, ‘We’ll try this and we’ll try that’. But it’s also the perfect introduction to what the game is, in that it is constantly reinventing itself. Even when you think you know where an individual story is going to go, it might have a hard right turn a few minutes later.”

The contrast between the vast, sprawling outdoors and the elaborate interiors of the Finches’ house are stark, and yet there’s still a hint of something monstrous inside; Edith herself likens it to “a smile with too many teeth”. Dallas had three words in mind when designing the house: sublime, intimate and murky. And while he’s not convinced the game quite delivered on the last of those three, he’s happy that Giant Sparrow struck a balance between the first two. “I think that’s most represented in the clutter on the walls,” he says. “A real house goes from being barren, where there’s nothing on the walls and it feels sterile and even videogamey, to being lived-in where you’ve got a couple of photos on the walls and that sort of thing. And then there’s this tipping point where you add too many things, too many photos and memorabilia, and it hits this point where it starts to feel like a natural force. It begins to look almost like the bark of a tree; something that has an order to it, but it’s too chaotic for us to be able to follow.”

Players are already primed to anticipate a kind of threat as they arrive: Edith is, after all, investigating the seemingly fanciful notion of a curse that is causing the Finches to die prematurely. It had been conceived as an anthology of stories from the early stages of development: one early concept placed Edith within a group of high-school students sharing tales with one another, before Dallas landed on the idea of a family and began to seek ways to tie them all together. Again, he looked towards the world of horror for inspiration. “The Twilight Zone has this continuity,” he begins. “I mean, it’s not really obvious what it is that Rod Serling and the music provides, but there’s a gestalt that unites these stories. So it became about finding a [narrative] throughline so that these stories didn’t feel completely random. Because it felt like they were all exploring similar themes.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Dallas also looked at Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years Of Solitude for structural inspiration, and found, once a couple of stories were in place, that interleaving them would allow Giant Sparrow to kill two birds with one stone. “We discovered a year or two into development that having the same locations and characters reappear was really powerful,” he says. “It wasn’t like we were just saving assets to use between stories; it was something that made the stories feel more interesting and specific to our game.” But the curse itself was a retcon. “Once we knew that all the stories were going to be about people dying, then [we had] to try and figure out a way to explain that.”

Yet the studio’s momentum could so easily have been derailed by a change of publisher. Having partnered with Sony in January 2013, the game being officially unveiled during 2014’s PlayStation Experience, it found itself without a publisher when the format-holder’s focus shifted away from indies. Fortunately, the transition to Annapurna Interactive in May of last year was a smooth one, thanks largely to the fact that several of the producers Dallas had been working with at Sony Santa Monica had moved across to Annapurna in the interim. “Four or five of the people that we interacted with most on a day-to-day basis had moved there,” he recalls. “And they had liked what we were doing before, and they just wanted us to continue, and perhaps to do a little bit more of it than we would have otherwise.”

Even when you think you know where an individual story is going, it might have a right turn

As a result, two of the game’s standout sequences were preserved. A more demanding original schedule would, Dallas admits, probably have led to some stories being cut, the two most likely candidates being those of Gregory and Lewis Finch. If you’ve played the game, you’ll understand what a loss they would have been. “They ended up in places we were really happy with,” Dallas says, “But they were not sure things for a long, long time. They were really hard to pull off.”

In the former case, there were worries, too, from Sony about how players might react to seeing a baby in peril. “People there who were parents were the ones who objected the most,” Dallas explains. “It was just about making sure that it was handled with the [appropriate] gravity and that it was respectful. That was definitely a concern early on.” But until all the disparate parts came together during the late stages of development, he admits it didn’t seem like it would be an emotionally demanding game to play. “You spend so much time looking at this thing as a bunch of designer art, with these crude models [where] there’s no music or sound effects and it crashes every 10 seconds, and you don’t take it that seriously when you look at it as a prototype,” he recalls. “It’s only at the end when it actually comes together that you think, ‘Oh, right, this is a real thing now.’”

Perhaps more significantly still, Giant Sparrow would have been forced to cut the story Dallas calls the game’s “capstone”. The tale of Edith’s brother, Lewis, who drifts away from his job chopping fish heads at a local cannery into an imaginative fantasy world, it’s arguably the most enthralling use of systems to communicate a story – and in this case, a character’s mental state – since Josef Fares’ Brothers: A Tale Of Two Sons.

A combination of an early ship date and the complexity of the sequence meant its fate hung in the balance for some time, as it went through several iterations. And then Giant Sparrow’s lead gameplay programmer left the project. Happily, his replacement saved the day. “We hired somebody new, who was amazing,” Dallas says. “The whole movement of the fish when you’re chopping had been fiddly and annoying and took a lot of focus, but our new programmer completely rewrote the way that it worked and suddenly it all started to gel.”

Meanwhile, a sublime horror of a very different kind factored into one of the other vignettes. The tragic tale of Barbara, a child star, is told within the pages of a grisly comic book; the surprise birthday party within the story came first, before Dallas turned his attention toward Tales From The Crypt and John Carpenter’s Halloween. He invited composer Jeff Russo to supply a version of the latter’s iconic theme, before wondering if it might be possible to obtain the rights for the real thing. Dallas even planned to ask Carpenter if he would voice the story’s narrator, though the SAG strike put paid to that idea. “I didn’t actually talk to John Carpenter [directly],” Dallas says. “I don’t know if it’s partly because he’s a big videogame nerd, but it was pretty straightforward. We asked; he said yes.”

It’s one of several playful flourishes in a game that, despite its subject matter, avoids lapsing into mawkishness. This was evidently one of Dallas’s biggest concerns, and it informed a number of storytelling choices, right down to the last line. “I was really nervous about any maudlin sentimentality, maybe to the game’s detriment,” he says. “One of the things we talked about a lot, right up until we shipped, was what Edith should say at the very end of the game – like, her last line. But I just feel it’s really manipulative to have something that is consciously trying to pull at your heartstrings like that. It’s ultimately unnecessary and kind of shoddy. For me, it starts and ends with empathy – it’s about creating a space where you are encouraged and allowed the time to feel empathy for someone else.”

The game’s anthological approach is clearly one Dallas would like to revisit in future, going as far as to suggest he’d love to see a group of developers collaborating on some kind of horror miscellany: the ludic equivalent of The ABCs Of Death series or found-footage collection V/H/S. “It’s worked really well for us,” he says. “I love that it gives you a chance to get in and out of stories before players have forgotten about them. I mean, I just started Metal Gear Solid V and I’m maybe three hours in, and I’ve already completely [forgotten] what was going on in the hospital at the beginning of the game and who those characters were. And I’m sure I’ll be asked to care about them later, but I won’t. It’s nice to have something that’s about 20-30 minutes long where you can still remember who everyone is and not have to hit people over the head with it.”