The Spiel des Jahres is the most prestigious award in boardgaming. Awarded annually by the German Game of the Year Association, it has three prize categories—Game of the Year, Connoisseur-gamer Game of the Year, and Children’s Game of the Year.

This year, however, the judges awarded a fourth prize—the Sonderpreis, literally 'Special Prize'. The prize is only given out in exceptional circumstances to exceptional games, and 2018 marks the first time in eight years that it has been awarded. It went to Pandemic Legacy: Season 2.

When I spoke with Rob Daviau and Matt Leacock, the creators of Pandemic: Legacy they had just returned from Berlin to receive the award. “It’s weird,” says Daviau. “In my mind the first [Pandemic Legacy] was kind of a raging inferno, a bright fire, and like a lot of stuff going on. The second one was received as a real warm glow. Just this positive note, but it wasn’t particularly loud. It was nominated for a few awards at the end of the year, and other than this very big one that we got in Germany didn’t win any of them compared to the first one.”

The Sonderpreis came as a big surprise for the pair. Perhaps it shouldn’t. Pandemic Legacy has been shattering expectations since Season One launched in October 2015. Within three months it had become the highest-rated game on BoardGameGeek, where it remained until very recently. It has transformed the careers of both Daviau and Leacock, and redefined perceptions of what boardgames can be. Not bad for an idea neither of its designers initially thought would work.

An Infectious Idea

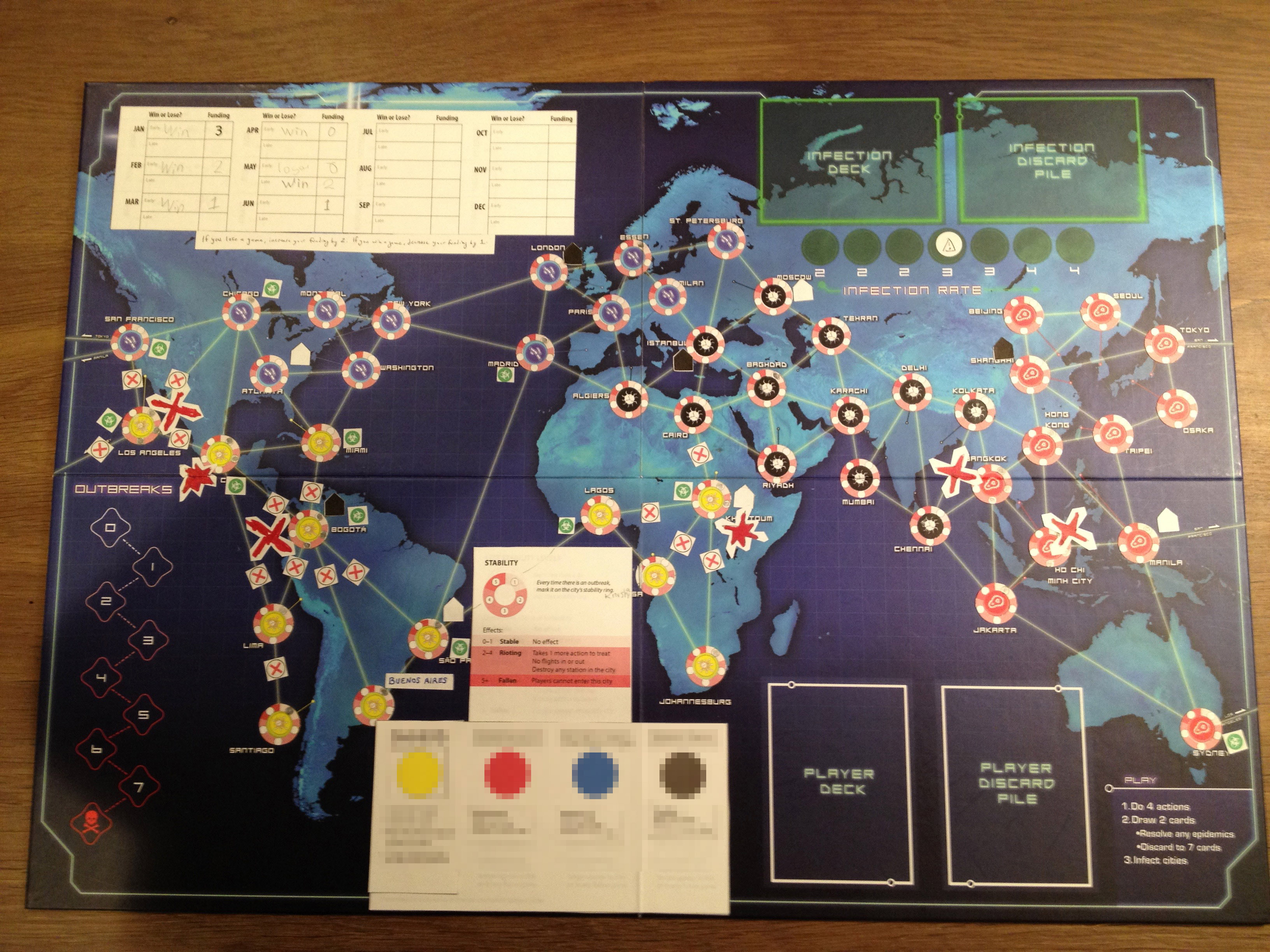

By 2013, Matt Leacock was already a successful boardgame designer. Pandemic, the cooperative game in which players try to save the world from a disease outbreak, had released in 2007 to both critical and commercial acclaim. Over the next few years it spawned multiple expansions and spinoffs, and its publisher, Z-Man Games, was always looking for further ways to spread Pandemic across the globe.

“We thought about ‘Oh we could do a card game, we could do a dice game, we could do a Legacy game.’ And um, that suggestion came up and I kinda laughed, ‘cause I thought, oh right, that’s gonna happen,” Leacock says. But the notion wouldn’t go away, and after a few months of Pandemic Legacy buzzing in his mind, Leacock began sketching out concepts for how it might work. “I was really, suddenly very hooked by the idea, and thought the best place to go would be to go look up the guy who invented the whole concept.”

Rob Daviau created his first Legacy game while still working at Hasbro. The idea arose during a conversation with his coworkers about Cluedo, in the form of a joke about why Dr Black repeatedly invites guests to his house when they keep murdering him. This sparked the idea for a boardgame where the board and the rules evolve each time it's played.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The idea debuted in 2011 with Risk Legacy, which took the vanilla mechanics of Risk and infused Daviau’s Legacy concept. Players would play through a campaign of fifteen rounds wherein the game would change radically. Players were encouraged to write on the board and rip up certain cards. Stickers could be added to the board that would permanently alter the rules. Risk Legacy even contained six sealed boxes that were gradually opened in specific circumstances, introducing whole new mechanics and features.

Risk Legacy wowed board gamers when it launched, and its success came just as Daviau left Hasbro after fifteen years. When he received an email from Leacock on the subject of Pandemic Legacy, he was intrigued, but sceptical. “I did caution Matt right at the beginning, saying “I don’t think this Legacy idea is gonna work with a coop [game],” Daviau says. “The only other one I’d done at the time was Risk… so I was very much in this mindset of players acting as checks and balances on each other.”

Fortunately, Leacock had plenty of experience designing games where the game has to do that balancing, and he had a plan for how to use the Legacy concept as a balancing agent. “I was looking at how each of the games could be a TV episode, and they could then roll over a longer, richer story,” he says. “And at the time we had a lot of Pandemic products out on the market as well. It was this rich soup of ideas that we could thread together, but use narrative to kind of stitch-em in a way so that they wouldn’t be overwhelming.”

...you’re constantly ripping these things up and destroying them. There’s prototypes all over the place.

Matt Leacock

The idea was that Pandemic Legacy would take place over the course of a calendar year, with players playing each month of that year at least once. With every month played it would evolve, introducing either new challenges for the player to overcome, or new tools to help them solve an already existing challenge. The notion of combining this with a strong narrative arc also appealed to Daviau, who started out in his career at Hasbro as a writer, and has always been keen on bringing story to boardgames.

The concept had great potential, but there were already a bunch of obstacles standing between design and execution. Leacock and Daviau live 3,000 miles away from each other, with Daviau based in New York and Leacock living in California. “I’m east-coast, he’s west-coast, and yet we avoid the usual battles that usually happen between east-coast and west-coast factions,” Daviau says.

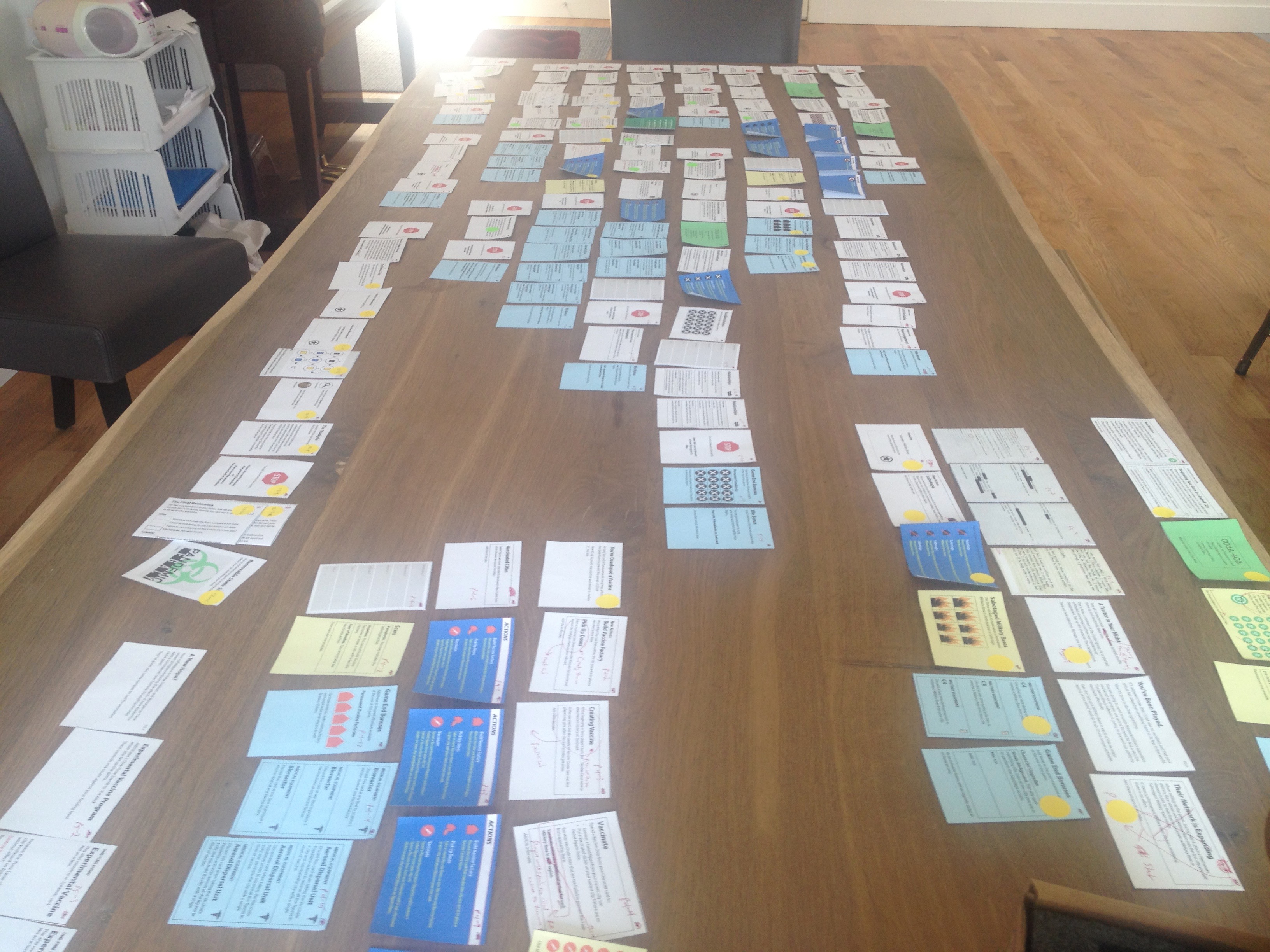

Creating a boardgame, which is a physical and tactile object, when its designers are working remotely from one another no mean feat, and Pandemic Legacy is no ordinary boardgame. “We each have prototypes on either end," Leacock says. “And we’re continually making them, so you know it’s basically you make something, and you put it out in the field and test it, you make another one, put it out in the field and test it, and you’re constantly ripping these things up and destroying them. There’s prototypes all over the place.”

Daviau puts their ability to overcome the physical barrier between them down to Leacock’s organisational skills. “Thank goodness Matt is hyper-organised, because I have done these sorts of video-chats or collaborations with other people, where I’m the organised one and it doesn’t go nearly as smoothly.”

Secondary Symptoms

There’s times to be super-organised and there’s times when you need to put it to the side a little bit and come up with bizarre ideas and hope they work out.

Rob Daviau

As well as being physically separated, the pair are creatively different. Daviau has a writer’s background, while Leacock spent many years as a software designer for AOL. To some extent, these backgrounds influenced the areas of Pandemic Legacy that they respectively handle. “The design is done almost entirely together, but we’ve evolved over the games where Matt really keeps track of the illustrator file that is the prototype, the 'kit' we call it, all the card and the board and, the thing that you print out to make it,” Daviau says. “And I tend to do more of the words. I definitely write the rules and a lot of the flavour text in the game. So it kind of turns into words and pictures when we execute, but even then there’s exceptions.”

Both men also responded differently to their times working for large corporations. Leacock has adopted many of the organisational systems he learned developing software. “I was just able to use that toolbox of techniques to work with partners remotely and keep everything kind of tidy. That just allows me to block off time to be creative.”

When Daviau left Hasbro, however, he rejected that style of working. “It was just a big, and for me oppressive, organisational system,” he says. “I’m sure it’s very practical, it’s just, you know, ‘I’m an artist!’.” During the years running his own business, Daviau has had to rediscover some of that discipline. “There’s times to be super-organised and there’s times when you need to put it to the side a little bit and come up with bizarre ideas and hope they work out.”

I asked Leacock and Daviau whether their divergent approaches to organisation and design ever cause conflict. Daviau says there’s been “natural disagreement”, but adds that it’s never descended into a “fight”. Leacock, meanwhile, believes they could do with more disagreement in their work. “It’s useful to have that kind of friction because it helps call out problem areas. So whenever I hear Rob disagreeing with something it’s like, ok, well, I really gotta step back and think about that.”

Several such problem areas appeared during the design for Season One of Pandemic Legacy. Figuring out how the twelve-month structure would work in terms of playing them as games was one. “If they just played twelve times a row, does that feel too much like you’re on a ride?” Daviau says. “But if we say ‘You’re gonna play March until you win?’ What happens if you lose seven times in a row?” In the end, they resolved this by giving players two attempts at each month, and included special 'funded event' cards that were added to the deck each time players lost, and removed each time they won, meaning the difficulty adjusted with the player’s ability to cope with it.

The other problem revealed itself during play-testing. “We brought it to an unpubbed, like a prototyping convention, and we played it with I think two different groups,” Daviau says. “Both groups were like ‘Love it, love it, love it great.’ And then they got to June and both were like violently, like “I don’t want to keep playing this, this is not Pandemic, this is not fun, this is—I don’t know what happened.”

Minor spoilers for Season One follow.

To bulk out the middle of Pandemic Legacy, Leacock and Daviau had devised a complex mechanic wherein players would perform a “search” action. Searching in a specific city revealed special story events and player abilities. “It was sort of like a separate game stapled onto the side of [Pandemic Legacy], and it just wasn’t quite working,” Leacock says. After trying to resolve the problem for three months, they eventually got the search action to work by stripping out nearly all of the complexity they’d baked into the concept. “I think what ended up going into the game was like five percent of what we had, or maybe less.”

Indeed, the whole seasonal concept, which is arguably Pandemic Legacy’s biggest innovation over and above the way it uses the Legacy mechanics, emerged simply because Leacock and Daviau had so many ideas that they went beyond the scope of one game. “They’re real marathons,” Leacock comments. “They absorb so much, you can throw so much at them when it comes to the design of the materials, the story that you can put in there. It’s so demanding as well. They take two or three times longer than any other games that I work on.”

By the end of 2014, Pandemic Legacy’s design was wrapped, but it would be another eight months before the game was in stores. Daviau felt like they’d done a pretty good job. “When you make a game you’re like ‘I think this one feels good, this should do well, this should get some good reviews. This is worth my time.'"

In October, it launched. Daviau and Leacock were blown away. “You don’t expect that. I still haven’t really internalised it to be honest,” Daviau says.

The Future Calls

The reviews for Season One of Pandemic Legacy were ecstatic. Within three months it had reached number one on BoardgameGeek, and would remain unchallenged for three years. Between 2015 and 2016 it won seven different awards. “People are like ‘What’s different now?’” Daviau says. “And I say ‘Well, in a lot of ways, nothing.’” I work from home, I get up, I’m in the middle of projects. Those projects haven’t changed…. But yeah, probably that summer I got on a few more podcasts, and then I started getting projects that were a better fit for me, which led to different opportunities which led to different projects. So it really was this rocket fuel to building a career that greatly influenced it and boosted it.”

Leacock’s response to Season One’s success was slightly different. “It certainly increased the pressure on Season 2. That was a little scary. It was so liked by the community it just kinda raised the stakes for the second one.”

By this point, Season 2 had already been in development for six months, but the explosive success of Season One nonetheless left the pair concerned about whether their plans for Season 2 could match the new level of anticipation. That said, Daviau believes this was better than starting Season 2 with no plans at all. “A lot of the pressure that we would have felt was mitigated,” he says. “We could use those findings to go ‘Ok, people liked this and didn’t like this.’ So we could revise it. But if we were starting January 1st with Season One as number one on BGG, and we were like ‘Now what?’ That would have been horrifying.”

Nonetheless, the challenge with Season Two was formidable. Mechanically it had to be recognisably Pandemic, but different enough so that people who had just played up to 24 games of Season One wouldn’t feel like they were starting game 25. The solution the pair came up with was to basically subvert all the player’s expectation that they had built up from Season One.

“Rob came out with this notion of ‘What if when you started the game you’ve already lost?’ Everything’s backwards and inside out, and that was kind of a fun principle that we followed for a lot of things.” Leacock says. “What if instead of removing cubes what if you’re adding them? What if you, like I said, you’ve already lost, the world is kinda gone, and you’ve have to put it back together again?”

With Season 2, the pair also wanted to give players more control in how the story unfolded, yet have it all add up to a coherent narrative. “The thing that clicked for me was the ability to set it in the future, but then have what was a history to the characters, but the future for the players,” says Daviau. “I mean it’s not Faulkner, you know, 800 pages of text. But being able to have a coherent world with a coherent story was a lot of fun to put together as a puzzle.”

But giving players more choice while also offering a strong narrative drive also made Season 2 vastly more complicated. “The board is probably the most complex boardgame I’ve ever worked on in my life,” Leacock says. “One of the risks of giving the players more autonomy is they can really hurt themselves a lot more if they go off the rails. So trying to design, like, little safety rails to make sure that you can’t completely fall off the rollercoaster was important… and really the only way we could do this was, we just did lots and lots of testing.”

Season Two released in 2017, and while the response wasn’t as explosive as that of Season One, most people acknowledged it as a superb follow-up to that first game. Now all eyes are on Season Three. No release date has been confirmed yet, and Daviau and Leacock are still hard at work on it, and are reluctant to talk specifics.

“We’re not done and we don’t know when it’ll be done, and when it is done it takes upwards of a year for it to get into people’s hands. And what we don’t want is to be in a position where we’re starting to talk about it, and then 9 months from now people are like, where is it?”

Regardless of how well Season Three performs, Pandemic Legacy's place in boardgaming history is already firmly established. Despite recently being knocked from the top of BGG by the mighty Gloomhaven, Season One is still generally regarded as the best boardgame ever designed, and it has changed the lives of both men forever. “It’s obviously made my career, which has been just fascinating and wonderful,” Daviau says. “I had a number of people come up to me at Gencon last week saying very heartfelt things about it in a way that I don’t expect to get from games. Like it was the most meaningful gaming experience they’d ever had. And they use words like that instead of ‘Oh, that’s my favourite game.’”

Leacock concludes by musing upon the creative experience Pandemic Legacy has provided. “I just reflect on how much fun I find designing these games,” he says. “The way you can structure, the way things come out. It’s just such a rich space. I have really enjoyed the process.”

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.