The making of Audiosurf, the synesthesia simulator

How an indie rhythm game that makes levels based on your mp3s became an early Steam success story.

A telling difference between today's indie games scene and that of 2008 is how excited Dylan Fitterer was to hear his game was going to be on Steam.

Audiosurf had just been nominated for three IGF awards in the categories of Technical Excellence, Excellence in Audio, and the Seamus McNally Grand Prize. As Dylan tells it, "Then I got a call from Jason Holtman at Valve who said, 'Hey, you want to sell this on Steam?' That blew me away. That was crazy to get an offer like that."

Audiosurf went on to win the audio category as well as the audience vote, but the bigger prize was that it became February 2008's top seller on Steam, both by number of copies sold and revenue, despite being an indie rhythm game that cost 10 bucks. It eventually sold over a million copies. Of course since this was 2008, it was one of only five games released on Steam that month.

Best Game Ever Dot Com

Getting to that point was a road as bumpy as any of the rollercoaster levels Audiosurf makes out of the music you feed it. Like a lot of designers, Dylan's first game ideas were way beyond his capabilities. "I was trying to build the biggest videogame possible, that incorporated everything," he says. "My first game I was working on was like Magic: The Gathering meets first-person shooter meets something else. Had everything in it, the one game that was all games. That was what I figured I'd just build, by myself."

After a couple of years hitting his head against that wall he changed tack and went as far in the other direction as possible. From then on he only worked on games that could be finished in a week. "What I did is I launched this website called bestgameever.com and put up this promise that I'm gonna release a new game every Friday just to see if I could actually finish some things. And one of the things that I finished on there was called Tune Racer."

Tune Racer auto-detected whichever CD was in your drive at the time—this was 14 years ago, so of course you had CDs near at hand—and then matched the tempo of that music to a simple game about a car racing along a tube, overtaking other cars. Two sequels followed, tweaking the idea so that cars had to be dodged around instead of just overtaken (an idea that would return as Audiosurf 2's Dusk skin).

There was clearly something to the idea, something that kept drawing Dylan back. When he eventually decided it was time to invest more than a week in one of his concepts, to monetize one of those bestgameever.com prototypes, it was Tune Racer he turned to. He figured he could turn around a deluxe version in "like a month."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Spoiler: it took longer than a month.

"You should probably usability test your game"

Dylan wasn't alone. His wife Elizabeth, who had a day job at Microsoft, helped him over the course of what turned out to be several years of work. The two encountered plenty of dead ends along the way. They even tried to give Audiosurf a plot for a while, though he doesn't recall the details. "My wife and I worked on a story, and I don't remember if the motivation was like as an extended tutorial, or if it was just this lack of confidence that a game with no story would be compelling for people," he recalls. "I'm not sure. It didn't come together. It wasn't a good idea."

That is so hard. Watching people play your game that you think is almost there and you discover that you're not even close.

Dylan Fitterer

What was a good idea was letting people use their own mp3s. Rhythm games with original scores have a hurdle to get over because players need to get used to the music before they can tap along with it, and even something like Rock Band can fall flat with players who don't listen to the bands it favors. Audiosurf's algorithm matches the curves of the track, the speed of your craft, and the placement of blocks to elements of the songs you choose, songs you already love. It transforms your mp3 collection into an explorable space.

"My absolute favorite thing was to play this track from OCRemix in the game's Mono mode. The simplicity of Mono mode and the intensity of the track made for a great flow experience."

—Ben Prunty, composer of FTL and Into the Breach

The big beat

But for most of Audiosurf's development, the placement of blocks wasn't in sync with the beat. "Those were basically random," Dylan admits. "I had convinced myself that didn't really matter. The track was shaped to the music and you just had these random patterns and you could maybe see the music in the patterns if you look hard enough or something. It made sense to me but Elizabeth, my wife, finally convinced me that was not a good idea."

The extra effort was worth it, although even then it wasn't a game that clicked with everybody. Some people sat down to play and don't feel the connection between the game and the song, no matter what music they choose. There just seems to be something in the way people are wired that determines whether it works for them or not. "We noticed that early on at trade shows. I think most people would see how it worked right away once they played, but some people get in and play and say, 'I don't see how it's synchronized to the music.' We'd be in there clapping and stamping our feet."

Another worthwhile idea was thorough playtesting, and not just at conventions. The value of seeing how new players react to a game repeatedly over the course of its development is impossible to overstate. "My wife did a lot on it before anyone else," Dylan says. "Toward the tail end she was working at Microsoft as a usability engineer in the Xbox group and so one night she comes home and says, 'You should probably usability-test your game.' 'Oh, yeah. That's a good idea.' We just hired friends and different people to play it and watch them play, and [we would] not talk. See where they get hung up. That is so hard. Watching people play your game that you think is almost there and you discover that you're not even close."

"I'll always connect Audiosurf to the voluptuous hillsides produced by Wuthering Heights, specifically the swell into the orgasmic walls of red. A decade on, I still shiver."

—Kieron Gillen, former PC Gamer editor and Audiosurf leaderboard champ

Going ninja

One of the ways Audiosurf began to differ from Tune Racer was that it wasn't just about avoiding obstacles. It stopped being a game about weaving between blocks and became a game about collecting them, matching three of a kind into the grid at the bottom of the screen. "Through that usability testing that my wife and I did, we discovered that that was really hard to teach," Dylan says. "It was hard enough explaining to people that you use your own music, that was foreign, then this other thing where you're playing a match-3 game on this racetrack to music, it was too much to teach."

Our timezones were so different that we'd have a call at midnight and tell them what we thought about the last batch of stuff and what we wanted the next day

Dylan Fitterer

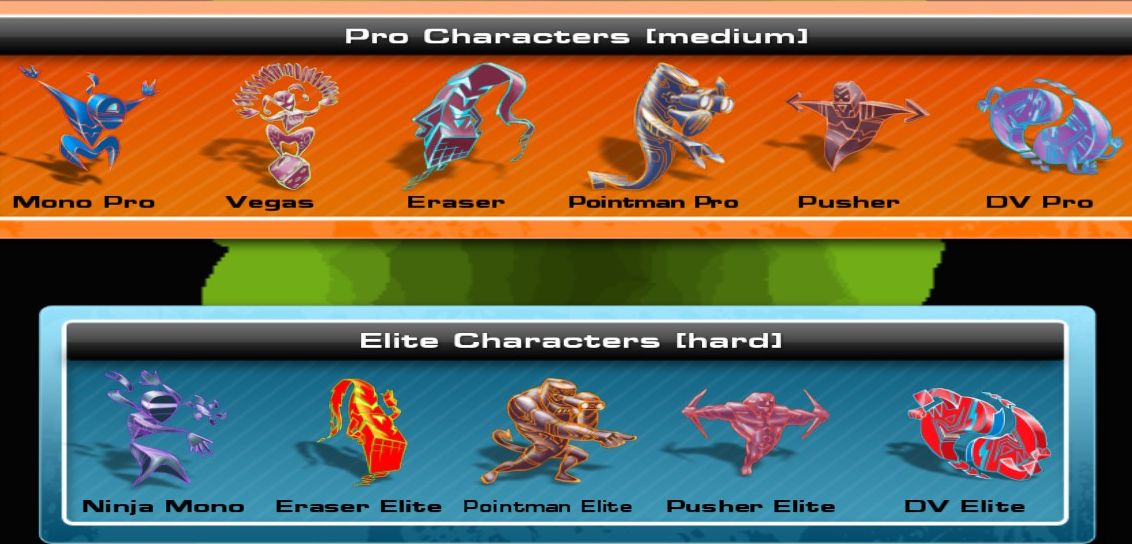

The optional mono mode was the solution. It simplified things by reducing the blocks to two varieties, one to collect and one to dodge. "I thought that would just be a stepping stone or maybe just a tutorial mode and then that ended up being super popular." Players wanted it to be more than just an introductory way of playing, so Dylan created 'ninja mono' as the hardcore variant, and it became the way most players experienced Audiosurf.

The Fitterers were helped across the finish line by several contractors, including artist Goran Delic who drew characters like the ninja for the select screen, and Paladin Studios, who built various 3D assets. "They did the vehicles and the geometry that's alongside the track and the squid that's at the end," Dylan says. "That was a week or two weeks of work, right before launch. That was a lot of fun. Our timezones were so different that we'd have a call at midnight and tell them what we thought about the last batch of stuff and what we wanted the next day and we'd get up in the morning and check it out and put new stuff in the game."

And finally, there was Valve. Their involvement went beyond just putting Audiosurf on Steam—it was the first third-party game given access to Steamworks, the full suite of tools Valve's games use for everything from leaderboards to achievements. It also shipped with the soundtracks to The Orange Box games packaged in, and selecting certain songs from Portal triggered a "secret level" where you have a portal gun and some of the blocks are companion cubes.

On Audiosurf's release those songs immediately became the most popular on its leaderboards, but competition broke out wherever players found songs that made particularly fun levels. So did arguments about which genres suited it best. "I don't think there is an objective best or anything," Dylan says, although he notes that his preference is for bands like Tool and Nine Inch Nails. "One of the things I like about industrial, Nine Inch Nails kind of stuff is it tends to have very big changes very rapidly, so a slow part, a very intense part, and that creates very cool moments."

Those moments of drama and intensity when everything lights up and the track swoops around at speed are key to the appeal of Audiosurf, and when you find out a song you love hits one of those it's even better. But as well as connecting you with music you're already into, Audiosurf has helped players discover new music. Dylan himself learned a lot about what was popular in 2008. "I was a little behind the times I think. Like Dragonforce, that was huge. 'What is this song everybody's playing?' Podcasts were funny, there were people playing podcasts. I hadn't thought to try that."

The Fitterers followed Audiosurf with a sequel and a VR spin-off called Audioshield. But some day, Dylan says he'd like to go back to bestgameever.com and see what other forgotten treasures it holds. "I still have the domain, I just have this lame little placeholder on there right now. I have that site backed up I keep meaning to get it back online. That'd be fun."

This article is part of the Class of 2008, a series of retrospectives about indie games that were released in 2008.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.