The legacy of Half-Life 2

November 16th, 2004 was a red letter day on both sides of the screen. The original Half-Life had redefined the FPS as an immersive experience instead of merely a series of missions, and no-one expected its follow-up to do anything less. Few were disappointed. In City 17, Valve created one of the most coherent and ambitious worlds ever seen in gaming—and if it looks a little primitive now, it’s because so many since have followed in its footsteps. BioShock Infinite’s opening for instance works almost entirely to Half-Life 2’s now dog-eared playbook, offering greater fidelity and a more exciting city, but recognizably the same style.

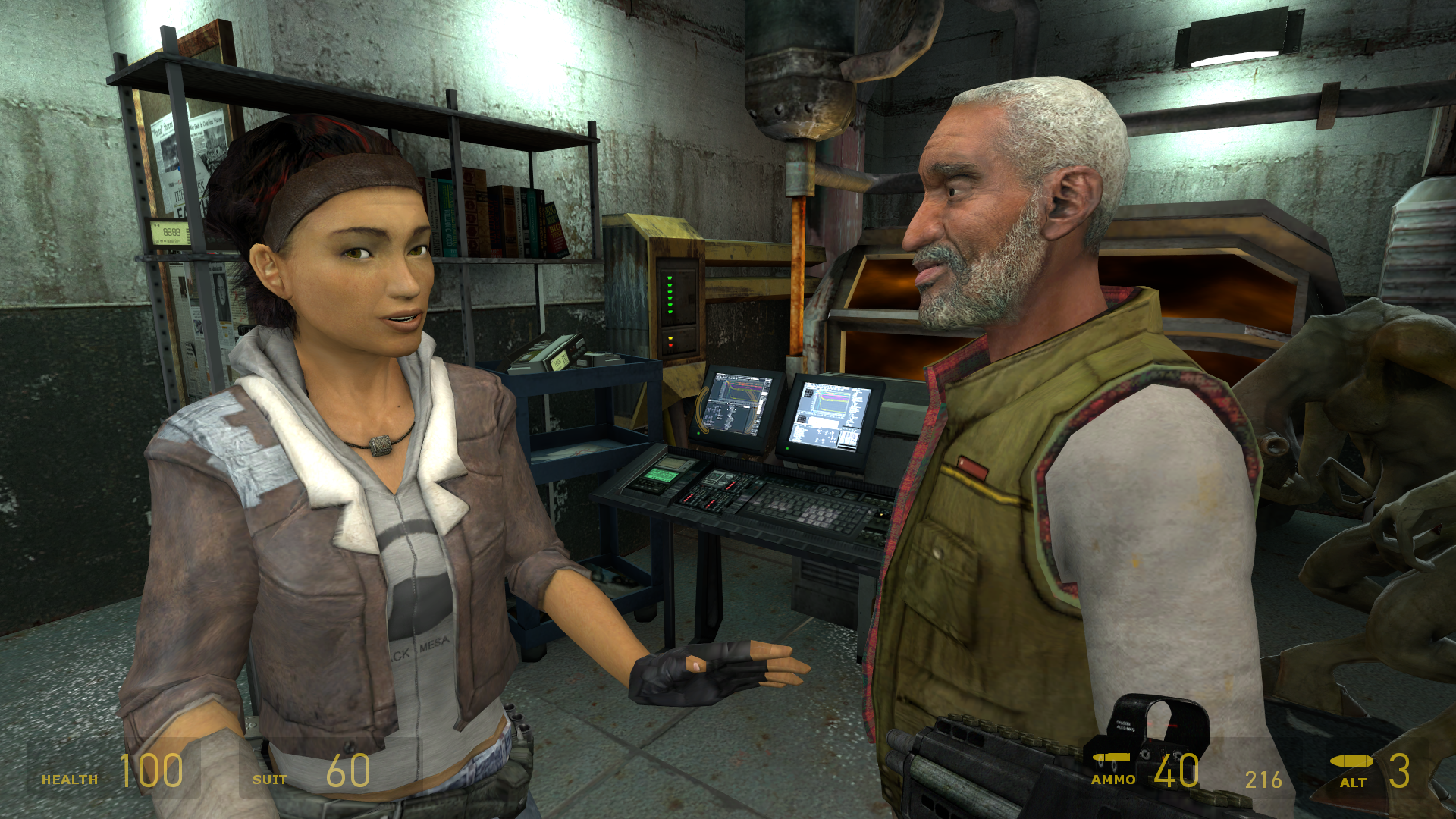

What Half-Life 2 really brought to the industry wasn’t new ideas… though it absolutely had them… but demonstration after demonstration of how things both could and should be. Alyx Vance for instance was an effective sidekick and a fun character, but it was her ability to make a connection with the player through things like eye contact that elevated her above her others—something shared by fellow Source engine game Vampire: The Masquerade: Bloodlines, especially with characters like Jeanette and your pet ghoul Heather. She could shoot a worried look. She could smile, and have the smile go further than her lips. She could go directly from being your wing-woman to interacting with the world, from having conversations to fixing something, all as smoothly as Half-Life managed to never break perspective as you went from random lab geek to savior of two different worlds. She’d even climb and vault over things instead of simply walking around the old fashioned way, easier as that would have been to script.

That sense of flow is what really defined Half-Life 2—sequences bleeding into one another to create the feel of an unbroken journey (give or take a loading screen). It was a game of smooth traversal around the maps, of combat bleeding into story, and each major section, most famously zombified Ravenholm, casually experimenting with the formula. Every cool bit offered something new and most left us wanting more, even if the radical shifts did take away much of the original Half-Life’s thematic consistency. Every not-so-cool bit, like the dull start of Sandtraps (a vehicle section that paled in comparison to what Valve was able to pull off by Episode 2) was short enough not to be that big a deal, and something else was always on its way. While admittedly the story sequences are interminable by modern standards, the action was all about peaks and troughs that allowed both intensity and time to savor the craft.

On top of that came the details; a hundred things designed to be absorbed rather than directly noticed. The soundscape for instance, with the Combine announcements using medical terminology to describe uprising—Gordon Freeman as a ‘staph infection’—or the Combine’s logo—an outreached claw almost, but not quite, absorbing a small world. It’s a subtle detail, but one of many told through level design rather than audio logs or cutscenes. Others include visiting rusted playgrounds of a world without children, and seeing the empty seas that have left ships high and dry—the terraforming inflicted on the natural world mirroring the shift from old and human to new and alien that you see throughout City 17.

One of the most subtle, though much borrowed since, is the way that Valve tends to show new mechanics off three times—first with no pressure, then some pressure, and then for real to be sure the player has grasped and understood it, before it becomes an assumed skill. The gravity gun for instance. First you just move a solid box into position to meet Alyx. Then her robot Dog throws other boxes at you for you to catch. Then, it’s zombie fighting time.

Speaking of fighting zombies, we can’t overlook the physics engine—used in Ravenholm to let you hurl sawblades. Half-Life 2 was one of the first FPS games to go big on physics, for two basic uses. The first was, honestly, showing off. They were a novelty then, which came through in a lot of puzzles like pushing barrels under a platform to be able to cross it. Looking back, they’re a little eye-rolling. At the time though, they were pretty cool. It’s no secret that Half-Life 2 was at least in part a demo of Source, with these bits standing out even at the time as largely the equivalent of early 3D card lens flare effects. Cool, but gimmicky. When it showed them off, or put us in a vehicle, it was at least partly saying “Look what we can do!”

The big benefit though was creating a world that felt ‘right,’ in stark contrast to the largely static worlds of the previous generation; of games like Return To Castle Wolfenstein and Medal of Honor. Again, yes, it’s a bit showy to have a guard at the start insist you pick up and throw a cup into a trash can just to shout “PHYSICS!” What mattered though was that from there you both feel the benefit of them in every interaction with the world, big and small, and immediately start bemoaning their absence in any game that doesn’t have them. The rolling and floating of flaming barrels in water. Debris flying off as it felt like it should.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It all added, in much the same way that the original Half-Life’s responsive skeletal animation system instantly made conventional frame-based animations intolerably stiff. When Valve called its behind-the-scenes book ‘Raising The Bar,’ it wasn’t kidding. Half-Life 2 was an amazing game, but its crucial, lasting influence was less about the new things it did (as important as they’ve been) as showing how the familiar deserved to be done.

Unforeseen consequences

Which of course brings us to its shining achievement—Steam. To sum up Steam’s unpopularity in 2004 would leave no words left to describe ebola, lawyers, or Piers Morgan. And not without cause. It was buggy, it was ugly, there was no missing that Valve was outright forcing it down our throats out of nowhere, and the much crappier bandwidth of the day made being told to download games of this size almost offensive in its arrogance. It would be a long, long time before Steam even got close to the service that at least most of us know and love today, instead of its name just getting tacked onto the words ‘ing pile of shit.’

But. With Half-Life 2, Valve had a game that managed to get the necessary traction to create the service we know today, and while nobody would claim it’s perfect, nothing else has done so much to legitimize and make digital distribution work. Much as it took Apple to break the music industry’s obsession with DRM on MP3 files, it took Steam to show the whole industry that the game had changed. The idea that you’d be able to redownload your games in perpetuity for instance was heresy to companies that at best wanted that to be another service. Being able to download them onto any machine instead of them being locked to a single PC, or maybe three, or five? That just wasn’t done. Valve was the first major company to build a digital download service that people actually wanted to use, that made the experience of buying games online better. Without Half-Life 2 though, who would have used it? Without that audience, who would ever have agreed to let a competitor sell their games? Half-Life 2 didn’t just give the FPS a shot in the arm, it changed the entire industry.

It wasn’t a perfect game. It was far more a series of cool things than Half-Life’s journey, it was heartbreaking to be taken out of City 17 almost immediately in favor of being consigned to the countryside, the story was primitive and a few of the set-pieces dragged on far too long. It held up pretty well for years, but looking back, yes, it’s now a bit long in the tooth. Few games though have had a more lasting impact in so many ways, or can be deservedly held up as both paragon and pioneer. Fewer still have done it so well, they’re still being copied decades later.

Now then, Valve, about that Half-Life 3…