The history of the first-person shooter

From Maze Wars to Overwatch, the FPS has enjoyed decades of innovation.

This article was originally published in two parts across PC Gamer issue 309 and 310. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US.

Writers of videogame histories often think in terms of individuals and periods—great innovators and clear-cut ‘epochs’ in design, typically bookended by technological advances. Events or people who contradict those accounts have a tendency to get written out of the tale. According to one popular version of the medium’s evolution, the first-person shooter was formally established in 1992 with id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D, a lean, thuggish exploration of a texture-mapped Nazi citadel, and popularised in 1993 by heavy metal odyssey Doom, which sold a then-ludicrous million copies worldwide at release. The company’s later shooter, Quake, meanwhile, is often held up as the first ‘true’ 3D polygonal shooter.

Founded in 1991 by former employees of software company Softdisk, id’s contributions to what we now call the FPS is undoubtedly immense. Between them, Wolfenstein 3D and Doom brought a distinct tempo, savagery and bloodlust to first-person gaming, and programmer John Carmack’s engine technology would power many a landmark FPS in the decade following Doom’s release. But we shouldn’t view that contribution too narrowly, as simply one step along the road to a game such as Call of Duty: World War II. And nor should we neglect the games—before, during and after id’s breakthrough—that took many of the same concepts and techniques in different and equally valuable directions.

The beginning: Maze War, Spasism, WayOut

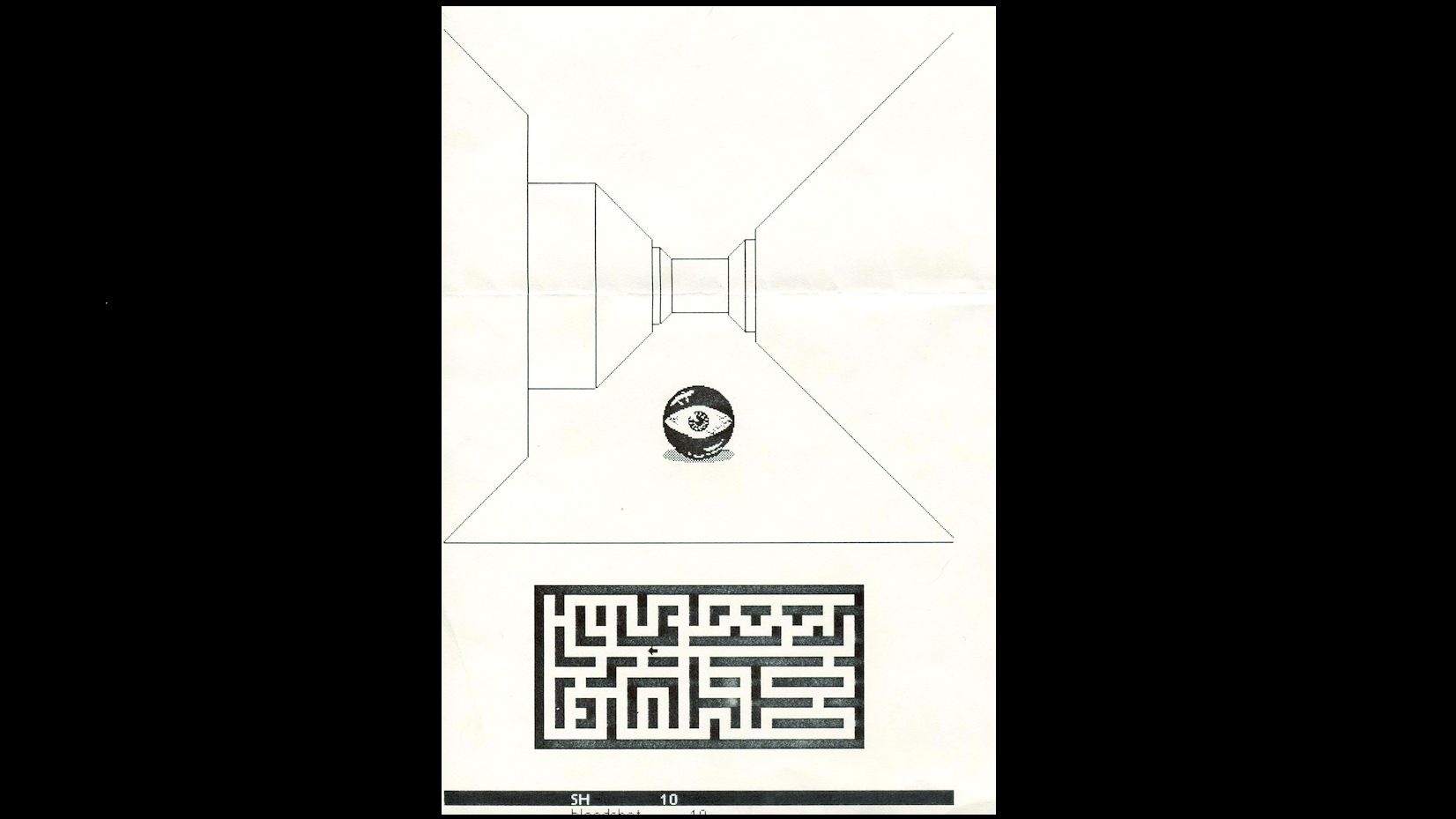

To think about the shooter’s origins is to think about labyrinths. Among the earliest pioneers of first-person videogaming is 1973’s Maze, a game cobbled together by high school students Greg Thompson, Steve Colley and Howard Palmer during a NASA work-study program, using Imlac PDS-1 and PDS-4 minicomputers. The three had been carrying out research into computational fluid dynamics for future spacecraft designs, an early show of what would become a problematic relationship between the commercial games business and the US military-industrial complex. Initially a single-plane, 16x32 tile wireframe environment for one player in which you’d turn by 90-degree increments, Maze grew to include shooting, support for a second player via serial cable, a corner-peeking functionality and indicators for which way the other player is facing.

After completing his spell at NASA, Thompson took the game with him to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. With access to a more powerful mainframe, and the aid of David Lebling—who would go on to create the legendary text adventure Zork and found Infocom—he added eight-player support over the US defence department-run ARPANET, a map editor, projectile graphics, scoreboards, a spectator mode and ‘bots with dynamic difficulty’, all features that would resurface in mass-market shooters many years later. Maze War was very popular on campus—it used up so much computing resources that the MIT authorities created a ‘daemon’ program to find and shut down sessions. In one of its later forms, the maze extended along the vertical axis and players could fly, shoot and take cover in any direction.

For better and worse, first-person shooters have long seen service as military training simulators. In 1995, the US Army created its own Doom mod in a bid to cultivate such skills as ammunition discipline at a fraction of the expense of physical training, following budget cuts in the aftermath of the Cold War. Made publicly available after Doom II ’s release, the mod sees a fireteam consisting of a leader, two riflemen and a machine-gunner tackling a range of real-life scenarios, including hostage rescue. It also replaced the original’s demons with generic human aggressors.

Marine Doom was never formally adopted as a training instrument, but paved the way for propaganda games such as the popular Unreal Engine shooter America’s Army.

If Maze War sounds like a fully-featured FPS in hindsight, it’s important to note that the category ‘first-person shooter’ is of much more recent inception—according to a 2014 study by the academic Carl Therrien, it only entered popular discussion around videogames in the late ’90s. Many studios, including id, preferred terms and slogans like ‘3-D adventure’, ‘virtual reality’ and ‘the feeling of being there’ when describing games that are played from a first-person viewpoint. Nor was the perspective exclusively, or even predominantly, associated with on-foot gunplay. There were racing games, such as Atari’s 8-bit arcade offering Night Rider, which treated the player to a dashboard view of a road made up of shifting white rectangles. There were cockpit simulators such as 1974’s Spasim (often granted dual honours with Maze War as the first-person shooter’s oldest ancestor), a 32-player space combat game in which unofficial approximations of Star Trek vessels wage war at a mighty one frame per second.

There were dungeon-crawlers such as Richard Garriot’s Akalabeth in 1976, which combined a top-down world map with first-person dungeon segments featuring coloured wireframe graphics. Maze War spawned a number of sequels and imitators, attractively billed as ‘rat’s-eye view’ experiences by a 1981 issue of Computer & Video Games magazine. The first-person shooter genre as we understand it today arose from the artistic friction between these approaches, shaping and being shaped by them in turn.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Naturally, methodologies shifted as new technology became available. Among Maze War’s more intriguing descendants is Paul Allen Edelstein’s WayOut, released for the Atari 8-bit in 1982. It made use of a rendering technique known as ray casting, whereby a 3D environment is generated from a 2D layout by sending out beams from the player avatar’s eyeball and drawing a pixel where they intersect with an object’s coordinates. Where light in reality bounces off many surfaces before entering the eye, ray casting simulates a ray’s collision with an object only once. While incapable of nuanced effects such as refraction, it was also much less resource intensive than other 3D projection techniques, which allowed for faster performance on the hardware of the day. If WayOut was a potent demonstration of ray casting’s utility, it is also worth remembering for its eccentric, non-combat premise. You play a clown trapped in a maze with a spinning, sinister ‘Cleptangle’ that will steal your map and compass on contact. A wind blows through the level, its direction indicated by floating fireflies. This interferes with movement, but also helps you get your bearings should you lose your map.

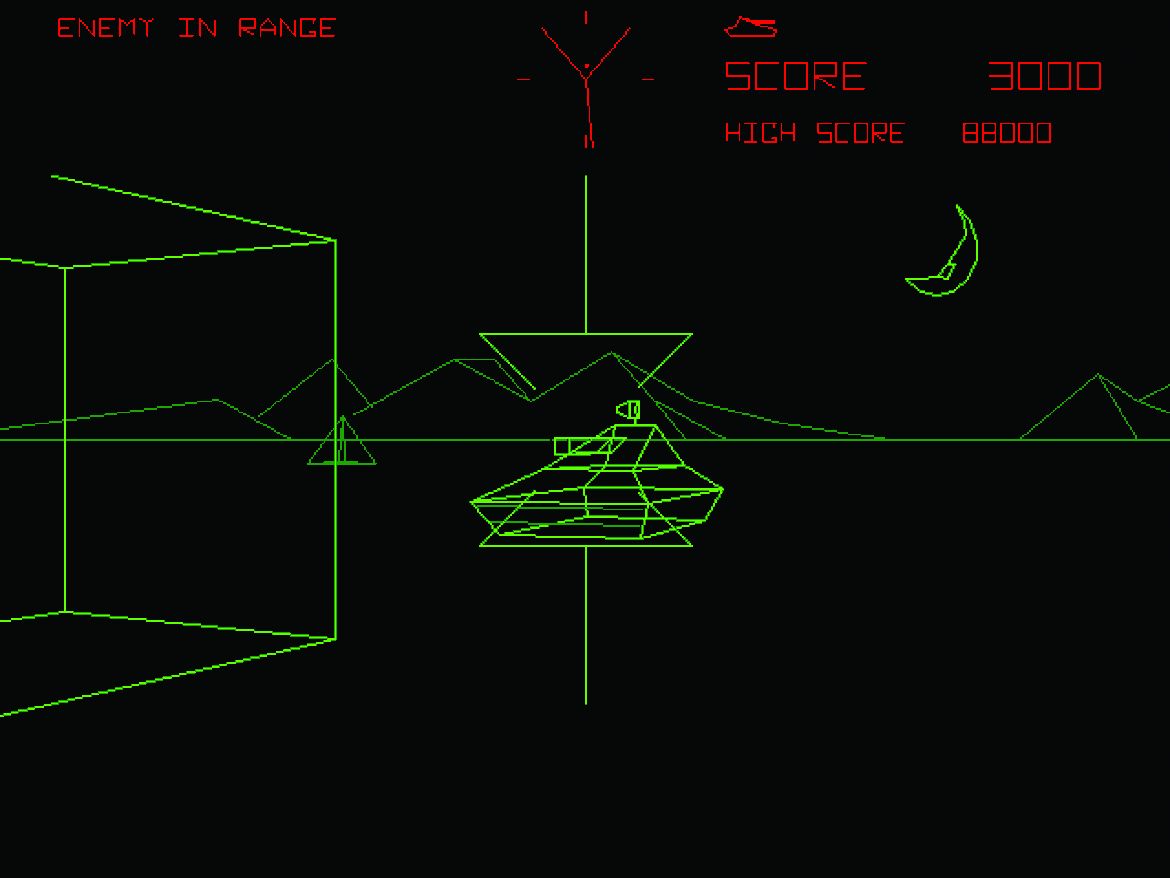

Cockpit simulations were especially popular during the ’80s, beginning with Atari and Ed Rotberg’s arcade game Battlezone, a tank sim featuring wireframe vector graphics that came with a novel ‘periscope’ viewfinder (the US Army would later try, and fail, to convert the game into a Bradley tank training simulation). In 1987, Incentive Software released Driller: Space Station Oblivion—the first game to run on its proprietary Freescape engine, which allowed for complex 3D environments dotted with simple geometric objects. The game assigned a sizeable chunk of the display to your offworld rover’s dashboard, a fat slab of buttons and indicators. In part, the prevalence of cockpit games reflected the influence of Star Wars, with its lavishly realised starfighter dashboard displays. But it also arose from attempts to make often-unwieldy simulation technology more convincing by representing players at the helm of a lumbering vehicle. Among id’s subsequent achievements was to narrow the gap between the player’s body and that of the avatar, thus helping to open a space in which ‘first-person’ denotes not merely a perspective but a narrative in which the player is protagonist.

Into the '90s: Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, Duke Nukem 3D

id’s career as a first-person developer began with Hovertank 3D in 1991. A cockpit sim brought to life with ray casting and featuring animated 2D sprites, it featured players searching for civilians to rescue and tentacular UFOs to blow up. It was followed by Catacomb 3-D—id’s first crack at a first-person character-led action game, with a visible avatar hand and portrait. Catacomb also featured texture maps, flat images attached to surfaces to create the illusion of cracked stone walls and dripping moss. In this respect, id had been strongly influenced by Blue Sky Productions’ breathtaking Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss, often cited as the first ‘immersive simulation’, which offered 3D, texture-mapped environments featuring sloped surfaces, rudimentary real-time physics and the ability to look up and down.

Wolfenstein 3D and Doom—both developed after John Carmack glimpsed Ultima in action at a 1990 expo—can be considered combative responses to Ultima’s representation of the possibilities of first-person 3D, eschewing the latter’s more complex geometry and gigantic array of variables in favour of pace and immediacy. Though busier with ornaments than Catacomb 3-D’s levels, Wolfenstein’s environments are designed to run at speed—designer John Romero once planned to let players carry and hide bodies, but dropped the idea to avoid bogging players down. Where Ultima set out to make players feel like part of its world via deep, consistent systems and a wealth of lore, Wolfenstein dealt in simpler, visceral effects—the sag of your avatar’s body when you take a step forward, the gore spraying from the pixelated torso of a slain Nazi. If the game pushed violence and politically charged imagery to the fore—somewhat to the distress of its publisher, Apogee—it also harkened back to the maze games of previous decades, with secret rooms to discover behind sliding partitions.

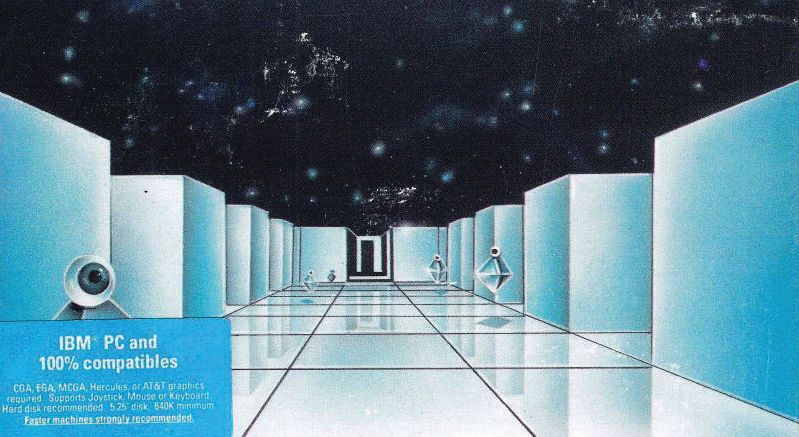

While not especially entertaining, David A Smith’s 1987 Macintosh adventure The Colony was one of the earliest first-person games to support free real-time movement. Initially developed on a machine with only 128KB of RAM, the game casts you as a crash-landed pilot investigating an outpost infested by geometric aliens, some of which shrink to peculiar eyeball artefacts when blasted. The game featured a drivable forklift truck, teleporters, cigarettes that kill you instantly and a monolith chamber that can’t be escaped. While not widely embraced at launch—Orson Scott Card was among its detractors—The Colony stands today as an important precursor to immersive sims like Deus Ex and System Shock.

This emphasis on the avatar’s bodily presence would set the tone for many subsequent shooters—notably Call of Duty, with its blood spatter damage filter—as would id’s sense that player participation should take priority over narrative elements. When it came to Doom, there was disagreement between Carmack, Romero and id’s creative director Tom Hall over how much plot and backstory to weave into the game. Hall had planned something akin to Ultima, with large, naturalistic levels built around a hub area and a multitude of arcane props. “Story in a game is like story in a porn movie,” was John Carmack’s infamous rebuttal. “It’s expected to be there, but it’s not important.” Hall eventually resigned in 1993. In his absence, the team stripped out a number of more fanciful weapons, turned many plot items required for progression into generic keycards, and cleaned up certain environments to allow for speedier navigation.

Loaded with taboo imagery, ultra-moddable thanks to id’s decision to store game data such as level assets separately from engine data as ‘WAD’ files, and equipped with four-player multiplayer to boot, Doom was a phenomenal success. Such was its impact that before ‘FPS’ became an accepted term, many in the development community used ‘Doom clone’ as shorthand for any first-person game involving gunplay. No game can claim to define a genre for long, however, and id’s work would attract plenty of imitators and rivals in the years to come.

Four months before Doom’s arrival, a fledgling Chicago studio founded by Alex Seropian and Jason Jones released Pathways Into Darkness, a Wolfenstein homage with a pinch of Ultima-style item puzzling. It thrust players into the boots of a soldier fighting through a pyramid in order to nuke a sleeping god before it can bring about the apocalypse. One of the few Mac exclusives available at the time, Pathways was hailed for its colourful hand-drawn art and menacing atmosphere. It deserves mention today for the ability to commune with the ghosts of other explorers using special crystals and elusive keywords—an engaging, melancholy approach to textual backstory. The developer, Bungie, would build on this concept during work on two of the 21st century’s best-known FPS series, Halo and Destiny.

Before Halo and Destiny there was 1994’s Marathon, the series often billed as the Mac’s answer to Doom. A suspenseful sci-fi offering set aboard a hijacked colony ship, it was a more complex game than id’s offering—adding free look with the mouse and a range of terrain dynamics, such as low gravity and airless chambers. It was also a more convoluted work of fiction, which relied on players scouring its open-ended levels for narrative artefacts. In place of the souls of the slain, Marathon offered computer terminals through which you converse with various sentient AIs about the wider universe.

Its sheer brilliance aside, Doom’s pre-eminence during the ’90s owes much to id’s embrace of the modding community, with players able to create their own maps using the developer’s own editing tools.

The game’s reach was limited by its choice of platform, but it attracted a dedicated community thanks to its elusive narrative backdrop and infectious eight-player, ten-map multiplayer. 1995’s Marathon 2: Durandal added co-operative play while 1996’s Marathon Infinity introduced a ‘Forge’ level editor, two features that would become central to the studio’s projects. Just as significant, however, was Bungie’s work in the emerging real-time tactics genre. Conceived by Jason Jones in a bid to stand apart from id Software, the top-down Myth games equipped Bungie with a feel for how different unit types and variables might react together. This would yield fruit in the shape of Halo’s famous combat sandboxes.

Its sheer brilliance aside, Doom’s pre-eminence during the ’90s owes much to id’s embrace of the modding community, with players able to create their own maps using the developer’s own editing tools (and thus, squeeze many hours of enjoyment out of the free shareware version). Fan concoctions ranged from Batman and Alien-themed conversions to trashy oddities like The Sky May Be, in which zombiemen moonwalk and the legendary BFG-9000 has a chance of conferring immortality on its target. Many up-and-coming designers cut their teeth on Doom mods, and other studios were eager to license it for commercial use. Among them was Raven Software, founded by Steve and Brian Raffel, which created the fantasy-themed shooters Shadowcaster, Hexen and Heretic using their own bespoke versions of John Carmack’s engine technology. The two companies were at one point based just down the road from each other, and formed an enduring bond—id would eventually hand Raven the keys to the Doom and Quake franchises.

Raven’s games were eclipsed, however, by the noxious excess of 3D Realms’ Duke Nukem 3D, a celebration of B-movie tropes that occasionally resembles a postmodern satire, and occasionally the aimless, chauvinist doodlings of a 13-year-old boy. Duke Nukem 3D is an intensely antisocial game, its levels grimy parodies of real-world locales, such as movie theatres and stripclubs, guarded by porcine coppers and strewn with the corpses of cinema idols like Indiana Jones and Luke Skywalker. While technically accomplished and formally inventive—it introduced jet packs, shrink rays, animated props such as arcade cabinets, physically impossible layouts and a protagonist who provides audible commentary throughout—the game is remembered today mostly for its jiggling softcore imagery. In years to come, shooter developers would spend as much time dispelling the notoriety Duke Nukem generated as they would profiting from his example.

Doom’s success also won the regard of franchise owners in other media. Maryland-based Bethesda—flush from the success of its eye-catchingly vast roleplaying effort, The Elder Scrolls: Arena—released a Terminator adaptation in 1995, endowed with lavish polygonal models. In hindsight, the game’s vast, cluttered wasteland feels almost like groundwork for the studio’s later first-person Fallout titles. In the same year, the venerable adventure game studio LucasArts shipped Dark Forces, the first Star Wars-themed FPS, inspired (and perhaps, annoyed) by the appearance of Death Star mods for Doom. LucasArts had designed a number of historical cockpit-based simulations during the late ’80s and early ’90s, but Dark Forces was a straight riff on id Software’s work. The developer’s impressive Jedi engine allowed for vertical looking, environments busy with ambient details such as ships landing on flight decks, a range of effects such as atmospheric haze, and the ability to stack chambers on top of one another.

Going 3D: Metal Head, Descent, Quake

By the mid-’90s, developers had begun to shift from so-called ‘pseudo-3D’ techniques such as ray casting to fully-polygonal worlds, capitalising on the spread of 3D hardware acceleration and the arrival of the first mass-market graphics processing units. Released for the Mega Drive’s 32X add-on in 1994, Sega’s lumbering Metal Head is often touted as the first ‘true’ 3D shooter. Pitching large, plausibly animated mechs against one another in texture-mapped urban environments, it was a handsome creation let down by repetitive missions. There was also Parallax Software’s Descent, released in the same year—an unlikely but gripping hybrid of flight sim and dungeon crawler with 360-degree movement. But the game now regarded as a byword for polygonal 3D blasting wasn’t, to begin with, a shooter at all.

John Romero had intended Quake to be a hybrid of Sega AM2’s arcade title Virtua Fighter and a Western roleplaying fantasy. Conceived back in 1991 and named for a Dungeons & Dragons character, the game would have alternated between first-person exploration and thirdperson side-on brawling. Romero envisioned circling dragons, a hammer massive enough to send shockwaves through the earth, and events that trigger when players look in their direction, such as glowing eyes appearing in a cave mouth. By the time John Carmack neared completion of an ambitious 3D engine in 1995, however, other id Software employees were exhausted and reluctant to depart too drastically from the Doom formula. There was also tension between the two founders over Romero’s supposedly inconsistent work ethic and Carmack’s view that the studio’s engine technology took precedence over its games. Romero ultimately resigned himself to a reimagining of Doom in polygonal 3D—and resigned from id Software itself after finishing the game.

In 1996, bestselling Cold War fantasist Tom Clancy founded a studio, Red Storm Entertainment, in order to adapt his universe of global intrigue and high-tech espionage into videogames. The developer’s debut, Politika, an RTS based on the novel of the same name, was a modest hit. 1998’s Rainbow Six, however, was a phenomenon built around a simple formula: one shot, one kill. Where peers dealt in surreal landscapes and superhuman capabilities, Rainbow Six focused on real-world situations, team tactics and keeping your head down and out of harm’s way. Its impact can be traced both in how today’s shooters incorporate stealth and in the fetishising of ‘special operators’ in games, such as Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

As Big Robot’s Jim Rossignol has noted in a 2011 retrospective, something of this failure lingers in Quake as it stands. Though cut from the same coalface as Doom—it offered fast, brutal gunplay, levels made up of corridors and arenas, and a multitude of secret areas—the game’s aesthetic and fiction are curiously divided, at once crustily medieval and high tech. You can expect banks of computer monitors and teleporters, but also broadswords and monsters ripped from the pages of Lovecraft. In hindsight, it plays like a representation of the tipping point from avant-garde into profitable convention, the point at which the chimerical possibilities of 3D action solidified into the features expected of a modern first-person shooter.

In at least one respect, though, Quake was transformative—it introduced a thrilling element of verticality, with players dashing through the air above opponents rather than simply strafing or corner-camping. This quality proved an asset in the emerging field of online multiplayer: by the late ’90s, Ethernet connections and modems had become ubiquitous and internet usage was rocketing. Quake’s multiplayer was initially designed for high bandwidth, low latency local area networks—it would check with a server before showing players the result of an action, which led to jerky performance online when there was a build-up of server requests. id swiftly released an update, titled QuakeWorld, which added client-side prediction. The result can be held up as the original esports shooter—software company Intergraph sponsored a US-wide tournament, Red Annihilation, in May 1997, which attracted around 2,000 participants.

As with Doom, Quake’s modding tools made it an attractive platform for amateur developers—its community gave the world Team Fortress, which would later flower into a standalone shooter, along with early specimens of machinima, including an epic known as The Seal of Nehahra. Its greatest descendent, however, would prove to be a shooter from a developer founded by Microsoft alumni Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington.

Created using a modified version of the Quake engine, Valve Software’s 1998 epic Half-Life remains extraordinary for how it reconciles the abstractions of game design with narrative tactics redolent of a novel (the game’s tale of secret government research and alien invasion was, in fact, written by a novelist, Mike Laidlaw). Its achievement versus earlier shooters can be summed up as the creation of temporal unity: almost everything is experienced in real time from the lead character’s perspective, with no arbitrary level breaks. In place of cutscenes, Valve weaves its tale through in-game dialogue and scripted events such as enemies smashing through doors—a tactic that both gives the player some control over the tempo and avoids jerking you out of the world. The game also sells the impression of a larger, unseen universe not via gobbets of textual backstory, but through the detail, responsiveness and consistency of its environment. The intro sees Gordon Freeman riding a monorail through Black Mesa, gleaning information about the location and your character from PA announcements and the sight of other employees at work. Following a disastrous experiment, you’re asked to backtrack through the same areas, now fallen into chaos.

Half-Life created a blueprint many FPS campaign developers would adopt in the new millennium. In particular, its seamless, naturalistic design would guide studios looking to explore realistic settings, such as the ‘World War’ periods. But it also introduced a note of unreality in the shape of Gordon Freeman’s murky reflection, the besuited G-Man—a personification of the game designer who sits a little outside Half-Life’s fiction. Together with the all-seeing, omnipresent AI manipulators of Marathon and the acclaimed cyberpunk RPG System Shock, the G-Man betrays a genre becoming increasingly aware of itself, and eager to turn its own structural constraints into a source of drama.

A new millennium: Unreal, Counter-Strike, Call of Duty

One of the greatest influences on first-person shooters at the turn of the millennium wasn’t a game, but a film: Steven Spielberg’s World War 2 epic, Saving Private Ryan. The movie’s thunderous portrayal of the D-Day landings would find echoes decades later in videogames like Killzone and Titanfall. Spielberg himself also has a robust association with game development: he co-founded DreamWorks Interactive with Microsoft in 1995 to work on adaptations of movies like Small Soldiers. Seeking a way to teach younger people about the war after wrapping up production on Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg asked DWI to develop a shooter, Medal of Honor, for Sony’s trendy new PlayStation platform.

Launched in 1999 to strong sales, the game was a watershed moment in several respects. On the one hand, its more earnest, grounded approach opened the genre up to players put off by the lurid sci-fi or pulp comic settings of games like Doom and Wolfenstein. On the other, it facilitated tense discussions about the right of videogame developers to depict such events, and the possibility that violent games spark violent behaviour. Medal of Honor released a few months after the Columbine massacre in Colorado, an atrocity that gave rise to a moral panic over videogame violence. Fearful of a backlash, DreamWorks Interactive removed all blood from the game before launch. It also attracted a heated reaction from the US Congressional Medal of Honor Society, and its president voiced his concerns to Spielberg in person. The game’s release, in spite of all this, created a precedent for other studios to comment openly on history and society.

The close of the ’90s also saw the release of the gorgeous Unreal, sparking a decade-long rivalry between creator Epic MegaGames and id Software. Conceived as a sort of ‘magic carpet’ experience where you fly through caverns dotted with robots, the game evolved into a bona fide Quake killer, running on a proprietary technology capable of 16-bit colour and ambient effects, such as volumetric fog. Like Quake, the game was designed to be modded easily and extensively. Also like Quake, its multiplayer left something to be desired at launch. Epic released a deathmatch-oriented standalone expansion, Unreal Tournament, in 1999, narrowly ahead of the arrival of id’s Quake III: Arena. A brace of colourful alternate fire options aside, it was notable for including both more competitive ‘hardcore’ and relatively playful ‘theme’ maps, such as levels floating in Earth’s orbit. The franchise found a dedicated following online, but the bedrock of Epic’s business would prove to be founder Tim Sweeney’s Unreal Engine, a highly modular entity designed for continual improvement. It would power games as diverse as Ion Storm’s legendary immersive sim Deus Ex and EA’s adaptations of the Harry Potter movies.

A collaboration between DigiPen Institute of Technology students and Valve, 2007’s Portal isn’t strictly speaking a shooter, but its outlandish physics puzzles and sense of level design and scripting as a form of coercion make it feel like a critique of Half-Life – a parallel the game’s wonderfully funny ending sequence plays up to. Based on the DigiPen game Narbacular Drop, Portal casts you as a human lab rat armed with a gun that creates portals, lost in a shifting mechanical labyrinth run by a malicious, yet utterly inept, AI. The Portal Gun itself is every bit as fun to mess around with as Half-Life 2’s Gravity Gun but the game’s unquestioned star is your nemesis, GlaDOS, a carnival mirror image of the AI antagonists from System Shock and Marathon.

Where Quake and Unreal Tournament dealt in cartoon bazookas and evaporating torsos, another 1999 release, Counter-Strike, set its sights on military realism. A Half-Life mod created by attic developers Minh Le and Jess Cliffe, it saw teams of terrorists and counter-terrorists struggling to arm or defuse bombs and rescue or maintain custody of VIPs, customising their loadouts with currency earned at the end of each round. The mod wasn’t a landmark success to begin with, but Valve’s designers knew a killer formula when they smelled it and scooped up Le and Cliffe along with the intellectual property rights in 2000. Counter-Strike became an enduring phenomenon, buoyed up by thousands of user-created maps (including David Johnston’s legendary Middle Eastern levels Dust and Dust 2) and a community as resistant to fundamental rule changes as any diehard fan of football. Perhaps the definitive esport shooter, its objective-based modes and tactics-driven design are integral to the DNA of competitive multiplayer today.

2000 was also the year that Microsoft acquired Bungie, thereby depriving Apple’s Mac of one of its more coveted games, a science fiction odyssey called Halo. The game had begun life as an open world exploration affair, running on Bungie’s Myth engine, and something of that luxuriant scale remains in the completed Halo: Combat Evolved, which was an enormous hit when it launched on Microsoft’s first Xbox console in 2001. Halo’s environments were bright, rangy and colourful, where other shooters were claustrophobic and dingy, and they were lent an intense overarching unity by the silhouette of the Halo ringworld itself, stretching up through each skybox. Its crowded encounters were far more open-ended than in most competitors, woven around delightful AI variables like Grunt footsoldiers kamikaze-rushing the player after you kill their leader. Its weapons retained something of Quake and Unreal’s excess—overcharging an energy pistol to strip an opponent’s shield in one go would become a standard multiplayer tactic—but its blend of finite player health and recharging overshields imposed a more studied, back-and-forth rhythm on firefights. Halo also showed off Bungie’s knack for world-building: the fascination of its wider universe would help cement its status as Microsoft’s flagship series.

Halo would be eclipsed, however, by another World War 2 shooter, created using id Software’s Quake III engine by Infinity Ward—a studio founded by veterans of Medal of Honor: Allied Assault with startup money from Activision. Released in 2003, Call of Duty was among the first shooters to let players aim down a weapon’s sights—a gambit that created a sense of fearful claustrophobia, narrowing your attention to the gun roaring in your hands, even as the game’s sprawling levels and battalions of AI troopers courted comparison with Allied Assault. It was a little overshadowed by Medal of Honor on PC, but Call of Duty’s popularity caught the eye of Microsoft, who asked Activision to develop an Xbox 360 port of the sequel. With Halo 3 still a couple of years away, Call of Duty 2 was a bestseller at the console’s 2005 launch. Mindful of the risks of hanging an entire series on a single developer, Activision brought on Spider-Man studio Treyarch to design Call of Duty 3 using the second game’s engine, giving Infinity Ward an extra year at the coalface. It was the beginning of a yearly alternation that, together with the franchise’s all-year-round multiplayer appeal, would allow Call of Duty to bury competitors and exert an out-sized influence on the genre at large.

Among Infinity Ward’s more ferocious competitors was a multiplayer-centric WW2 game created by Swedish developer DICE. Battlefield: 1942 saw up to 64 players tussling for capture points on enormous, open maps. Where Call of Duty’s own multiplayer came to prioritise pace and lone wolf virtuosity, Battlefield emphasised squad composition, the canny use of strategic resources such as vehicles, and above all, depth of simulation. The developer’s Refractor engine allowed for such crude feats of real-time physics as using TNT to launch a jeep across a bay onto an aircraft carrier’s deck. Though never quite a trendsetter in the increasingly lucrative console market, in large part die to its anaemic campaign options, Battlefield’s scale and freedom were a tonic for armchair generals weary of vanilla deathmatch.

Crytek’s Far Cry had a similar appeal. It began life as a glorified tech demo, the catchily titled X-Isle: Dinosaur Island, but flowered with Ubisoft’s backing into the first open world FPS in the current sense of the term. Where other shooters taught players to keep pushing forward, Far Cry allowed you to run amok in a vast tropical environment, using the undergrowth for cover while tracking unsuspecting soldiers through your binoculars. The series would go onto enjoy a symbiotic relationship with Ubisoft’s third-person Assassin’s Creed games, each experimenting with new ways to structure and diversify an open world.

Half-Life 2, CoD4: Modern Warfare, Bioshock, Crysis

If Far Cry was one of 2004’s highlights, it and every other game that year was utterly dwarfed by Valve’s Half-Life 2. While not as transformative in terms of storytelling craft as its predecessor, the new game’s post-alien invasion dystopia was a work of unprecedented delicacy. Where older shooters looked to B-movies for inspiration, Half-Life 2’s incompletely terraformed city compares to mid-20th century Communist eastern Europe (the game’s art director, Viktor Antonov, hails from Bulgaria)—at once grand and ground down, alternating steely megaliths with trash-strewn riverbeds and grubby prisons. Its principle opponents aren’t bug-eyed monsters but masked enforcers wielding batons and carbines, their presence given away by indecipherable radio chatter. It’s also, for all its linearity, a celebration of player agency, handing you a Gravity Gun that allows you to pluck and hurl sawblades at enemies, solve slightly goofy seesaw puzzles and pile up objects at whim. The game was widely imitated, within the first-person shooter genre and without, but arguably its greatest legacy is Steam, Valve’s now-globe-straddling desktop games store. It’s hard to imagine players embracing the clunky 2004 version of Steam quite so readily, were it not required to play Half-Life 2.

If Valve’s offering set the standard for FPS design (in terms of its campaign, at least) it was Call of Duty that swallowed up most of the limelight during the ’00s, the critical year being 2007. Weary of World War 2 and conscious of the need to differentiate its offering from Treyarch’s, Infinity Ward decided to transport the series to the present day. The result, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, unlocked a brand-new vocabulary for the first-person shooter. It traded the mud and everyman heroics of WW2 experiences for a slick, cheerfully amoral celebration of western military hardware and urban combat tactics—arming the player with laser sights, ghillie suits, Stinger launchers and drones. It also courted topicality where games like Medal of Honor had tried to distance themselves from the headlines—one level sees you living out the final moments of a country’s deposed president, while another puts you at the controls of an AC-130 gunship, in scenes familiar from news footage of the Iraq War. But what it is mostly remembered for today is the multiplayer. Infinity Ward’s decision to introduce a levelling and unlocks system derived from roleplaying games is the most influential sea change in shooter design during the past decade. Its notion of an online career, whereby players kept plugging away for small rewards rather than just enjoyment, also helped popularise the emerging concept of the game as ‘service’.

Bioshock's combat, which married chunky period firearms with pseudo-magical powers or ‘Plasmids’, would prove its weakest element. More intriguing was the universe of cruelty and hubris it sketched.

Call of Duty 4 wasn’t the only game to do a little genre-splicing in 2007. Irrational’s BioShock began life as a spiritual follow-up to the System Shock series—its creative director, the soon-to-be-famous Ken Levine, was a designer on System Shock 2—but over time it became more of a shooter than an immersive simulation or RPG. It casts the player as an airplane crash survivor exploring a disintegrating undersea ‘utopia’ created by a renegade industrialist, in a thinly disguised meditation on the philosophy of Ayn Rand. The game’s combat, which married chunky period firearms with pseudo-magical powers or ‘Plasmids’, would prove its weakest element. More intriguing was the universe of cruelty and hubris it sketched, a labyrinth of leaking glass tunnels and domed Art Deco plazas.

Building on Half-Life 2’s example, Irrational left much of Rapture’s backstory for players to discover in the form of audio diaries, graffiti and random bric-a-brac. Its environmental storytelling would attract legions of imitators across several genres, from Raven Software’s unfairly overlooked 2010 shooter Singularity through body-horror masterpiece Dead Space to so-called ‘walking simulators’ like Gone Home. It also formed part of an ongoing conversation about games as a means of rousing empathy or exploring moral quandaries. BioShock’s signature characters are the Little Sisters, mutated little girls who collect genetic material from corpses under the eye of their powerful guardians, the Big Daddies. Having disposed of the latter, you can either spare Little Sisters or kill them to harvest their ‘ADAM’, a resource you can use to upgrade your own powers.

The late ’00s saw the rise of the open world shooter, with Crytek’s fearsome Crysis swaddling the player in power armour in order to battle aliens on yet another overgrown island wilderness. The game was sold as an exercise in technological masochism, its detail, lighting and plethora of effects ‘melting’ all but the most expensive PC hardware. But its real trump card was the ability to enhance your Nanosuit’s agility, strength or endurance on the fly by drawing power from a finite reservoir, making it an engaging risk-reward system. It was soon eclipsed, however, by the Far Cry series, which Crytek had by now sold to Ubisoft. That’s both in spite of and thanks to Far Cry 2, an astonishing, bruising shooter stretched across 50 kilometres of African brush. Drawing on his experiences with the Splinter Cell games, designer Clint Hocking set out to create a brutal, Heart of Darkness-esque sandbox in which players fought malaria, self-propagating fire and bullets simultaneously. The results were arresting, but also frustrating, thanks to a patchy narrative, alternately dim or eagle-eyed AI and an unfair enemy respawning system.

From Doom onwards, the FPS has enjoyed a fruitful rapport with horror games. Most of the biggest names include a level or two that takes inspiration from the likes of Resident Evil. Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare has its spooky hoverbike trip through a quarantined Detroit, Half-Life 2 has its legendary Ravenholm level and Far Cry includes fever dreams where the designers are free to invoke the paranormal. A number of studios also work across genres. Monolith’s FEAR games are a captivating marriage of heavy ordnance and poltergeist activity. 4A’s Metro games, meanwhile, pack all the narrative texture of the Stalker series into a series of half-collapsed tunnels—though light on jump scares, the first instalment is one of the eeriest games you’ll play.

2012's widely acclaimed Far Cry 3 removed much of the frustration, and a little of the sophistication. It opened out the terrain, fine-tuned the AI to be more predictable, and put capturing enemy outposts—each a potted stealth-combat puzzle, inspired by the Borgia towers in Assassin’s Creed 2—at the heart of exploring the map. It also created a combo system, with players chaining melee executions into ranged takedowns, reflecting a growing interest across the industry in fluid first-person animations, epitomised by DICE’s 2008 parkour game Mirror’s Edge. Less positively, it traded the second game’s understated, callous portrayal of a perpetual civil war for a farcical story about whiny, kidnapped backpackers wrestling with the definition of insanity.

Players unconvinced by Far Cry or Crysis had a number of rival open world shooters to choose from. One of them was the Stalker series, inaugurated by Ukrainian developer GSC Game World in 2007, in which scavengers pick their way through radioactive ruins while keeping a look out for monstrous creatures and invisible, fatal anomalies. Stalker’s supporting systems were remarkable—at one point, the AI was allegedly capable of completing the game by itself—but its punishing survival simulation ethic limited its audience.

Gearbox's RPG-shooter Borderlands took a friendlier, trashier tack. Released in 2009, it saw you touring an anarchic, comic book-style planet as one of four classes, hoovering up procedurally generated (often borderline-unusable) weapons. Part of Borderlands' success, the novelty of its arsenal aside, was its humour—a rare quality in an often po-faced genre.

The turn of the decade saw a number of long-running FPS series beginning to lose momentum. Most obviously, the Medal of Honor series underwent an abortive attempt at reinvention in 2010, with publisher EA looking to fill gaps in the schedule between Battlefield instalments. In jumping forward from WW2 to present-day Afghanistan, the once-proud series merely left itself open to unflattering comparisons with 2009’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. id Software's properties were also at low ebb. Though an accomplished horror experience, 2007's Doom 3 lost out to Half-Life 2, while Quake had all but evaporated following Quake 4's muted reception in 2005. Raven Software's 2009 Wolfenstein reboot doubleddown on the paranormal aspects of the series backstory, to mixed effect. Following a similarly lukewarm response to Singularity, parent company Activision retasked the studio to help out with the Call of Duty series. RAGE—id's only new IP during these years save mobile game Orcs & Elves—proved a visual extravaganza and a gratifyingly hefty, Mad Max-ish shooter, but all too often felt like it was playing second fiddle to its own graphics technology. id’s old foe Epic, meanwhile, was increasingly dedicated to the third-person Gears of War series and its flourishing Unreal Engine business.

Call of Duty continued to reign supreme, though it attracted increasingly stiff competition from EA’s Battlefield—a franchise increasingly (and a little unfairly) pitched as a freeform "thinking man’s shooter", more respectful of player agency than the linear, attrition-driven Call of Duty. After experimenting with a lighter, buddy-comedy vibe in the Bad Company spin-offs, DICE amped up the grandeur with Battlefield 3, a multiple perspective tale of abducted nuclear weapons set partly in Iran (the bestselling instalment until DICE's journey into WW1 with Battlefield 1). The series had become famous for its Frostbite engine technology, which among other things allowed for real-time terrain destruction in multiplayer: participants could do everything from blasting out spyholes in walls to levelling buildings.

The modern era: Titanfall, Destiny, Overwatch

Call of Duty's greatest existential threats, however, were a mixture of internal discord and external market pressures. In March 2010, Activision—now by far the industry’s largest publisher, following a mega-merger with Vivendi and its subsidiary Blizzard—fired Infinity Ward cofounders Jason West and Vince Zampella over alleged insubordination. A few weeks later, West and Zampella announced the foundation of new studio Respawn Entertainment. A wave of lawsuits and countersuits followed, alongside a mass exodus of staff from Infinity Ward to Respawn. Activision was forced to call upon the recently founded Sledgehammer Games to help the depleted Infinity Ward finish Modern Warfare 3.

While the series weathered this crisis—thanks largely to Treyarch's pop-savvy, hallucinogen-crazed Black Ops subfranchise—Activision and other publishers also had to manage a problem of budget versus expectation. Scripted corridor campaigns in the Half-Life vein were proving increasingly expensive, thanks largely to the cost of HD art assets, and telemetry showed that players spent the bulk of their time in multiplayer. However, attempts to remove singleplayer from the package led to an outcry. Among the teams that struggled with this problem was Respawn. The EA-published debut Titanfall pioneered the concept of campaign multiplayer, with narrative elements, such as picture-in-picture cinematics, dropped into rounds of team deathmatches. The game was enthusiastically received—a mixture of towering mech combat and nimble parkour duelling, it restored something of Quake and Unreal Tournament’s agility to a genre that had become bogged down in cover combat. Its audience tailed off swiftly, however—many first-person shooter enthusiasts found the mechs-and-pilots premise to be more of a novelty than a game-changing fixture, though the larger problem was perhaps that, on consoles, Titanfall was exclusive to the Xbox brand.

Other shooter developers ‘rediscovered’ mobility during this decade—Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare and Black Ops III dabbled at length with powered exosuits, while Halo 5: Guardians added boost slides, double-jumps and ground-pounds to Master Chief’s moveset. But the game that brought it all together was 2014’s Destiny, the work of erstwhile Halo developer Bungie, now free from producing games solely for Microsoft. It was a mixture of MMO-style looting and Titanfall-esque acrobatics, all bundled up in an aesthetic that is reminiscent of the ’70s space race and classic sci-fi book cover illustrations.

Destiny is in some ways quite a soulless game: it's as grindy as Borderlands and far less self-deprecating, but its ruined yet sumptuous environments have an irresistible mystique. It also feels tremendous in the hands, with some beautifully judged weapon designs and class abilities.

Destiny has become one of Activision's flagship shooters, as has Blizzard's joyful arena shooter Overwatch, released in 2016. Overwatch is a lovely game to end on because it is essentially an interactive genre history, a celebration of its triumphs, foibles and even failures. It doesn't merely reach out to weapons, gadgets and abilities from other shooters, but also their quirks, exploits and the antics of their communities—Quake's rocket jumping, aimbots from Counter-Strike and internet edgelords in general. Its heroes are love letters to 30-odd years of genre history. Pro-gaming celeb turned mech pilot D.Va is both a potted Titanfall and a parody of the noxious "gamer girl" stereotype, for instance. Soldier 76, meanwhile, is Call of Duty man.

Even as it pays tribute, however, Overwatch also points to the future—be it in the effortless way it folds in concepts from fighting games and MOBAs, or in how it extends the FPS cast-list well beyond the muscular, dudebro protagonists beloved of so many rivals. It speaks to the enormous range of concepts that make up the modern FPS, for all its myriad hang-ups—a genre that has always been about so much more than firing a gun.