The forgotten origins of JRPGs on the PC

While the golden age of JRPGs was on the console, their genesis started on the PC.

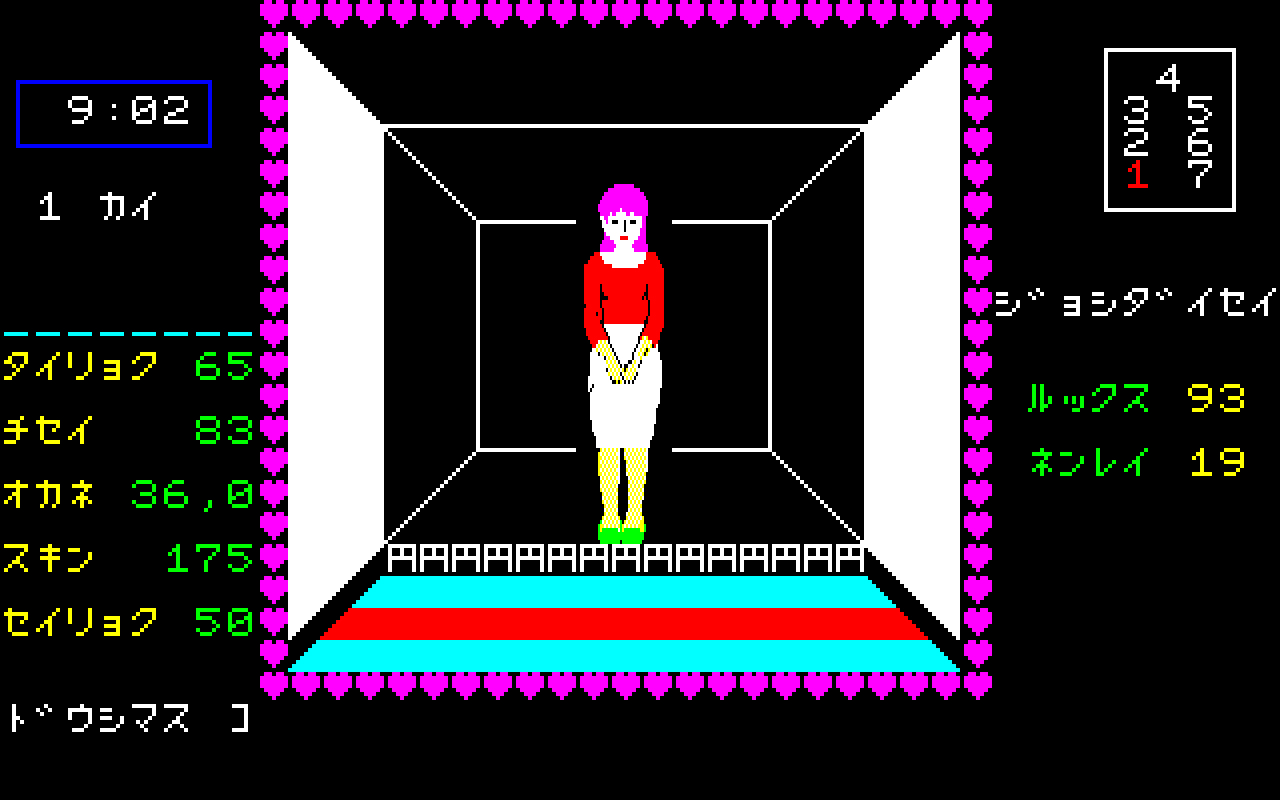

Long before Dragon Quest would ignite a golden age of Japanese roleplaying games, there was Seduction of the Condominium Wives. Forget genre tropes like heroic knights and evil dragons: this proto-JRPG was about a salesman going door-to-door trying to peddle condoms to lonely women while battling off Yakuza gang members and ghosts. Released in 1982, Seduction of the Condominium Wives was one of the first Japanese RPGs—if you can even call it that.

With Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, and Suikoden, it's easy to see why JRPGs and home consoles like the SNES seem inextricably linked. The truth is that a decade before these games rose to global prominence, Japanese developers had been designing RPGs on personal computers. Not all of them were hilariously sleazy eroge games like Seduction of the Condominium Wives, but they're crucial in understanding where the genre comes from and how its defining conventions, like an emphasis on character-driven storytelling, came to be. JRPGs might be remembered for their 16-bit golden age, but it's their forgotten genesis on the PC that paved the way.

The dark ages

The origins of Japanese RPGs is often attributed to Wizardry, a hugely successful western RPG designed by Robert Woodhead in 1981. There's no denying that Wizardy—and to a similar extent Richard Garriott's Ultima—had a huge impact on JRPGs. In the September/October issue of Computer Gaming World, columnist Roe R. Adams describes Woodhead's and Garriott's fame in the East: "Both Wizardry and Ultima have huge followings in Japan. The computer magazines cover [Richard Garriott] like our National Inquirer would cover a television star. When Robert Woodhead, of Wizardry fame, was recently in Japan he was practically mobbed by autograph seekers."

But the truth is that before either game was imported to Japan, a thriving development scene of proto-RPGs had already taken hold. In 1982, Japan's videogame industry was booming. Arcade games like Nintendo's Donkey Kong had come out a year earlier and sparked a golden era of videogame mania. While Japan was allegedly facing a shortage of 100 yen coins from the success of arcade games, its personal computing industry was also booming. Companies like Nippon Electric Company (NEC) were coming out with innovative hardware like the PC-8001, which is where the first Japanese RPGs would arrive.

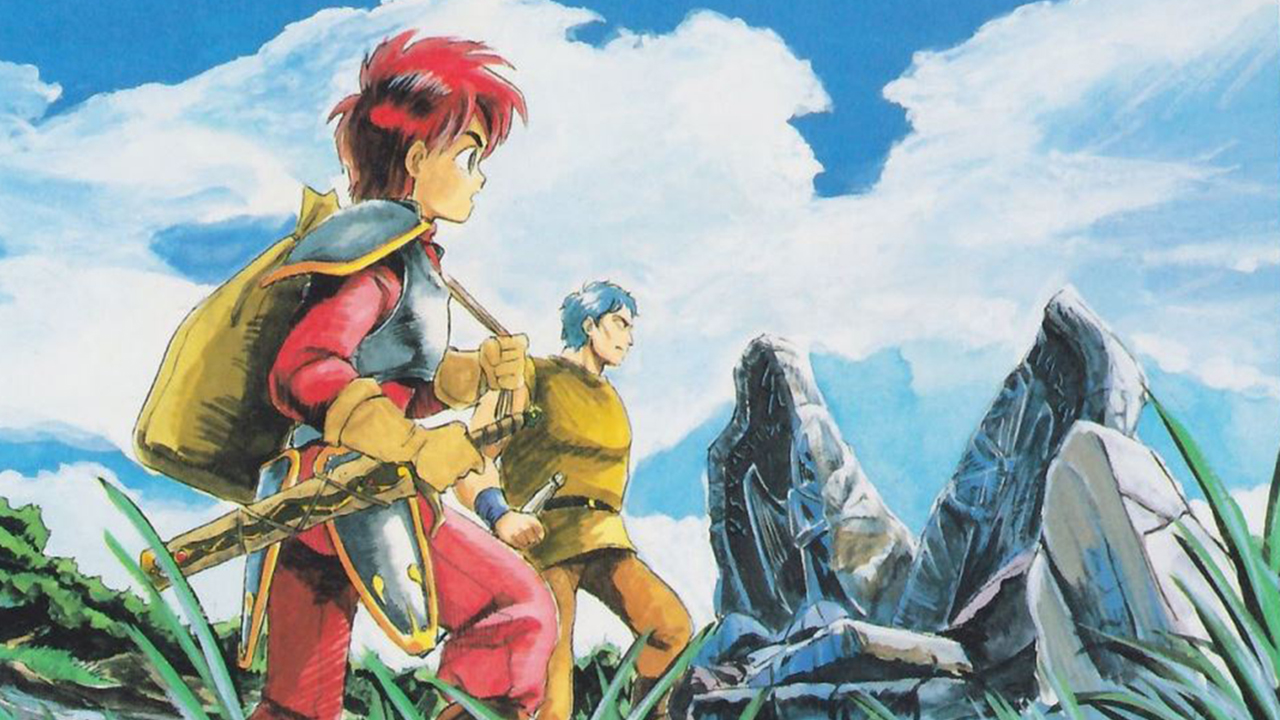

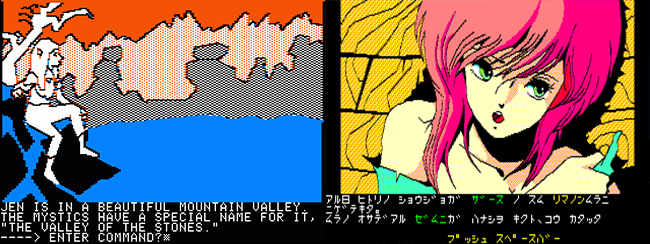

JRPGs are well-known for their visual style. Partly due to the prolific work of artists like Akira Toriyama (creator of Dragon Ball and character artist for Dragon Quest) but also because Japanese PCs like the PC-8801 (the successor to the 8001) needed higher resolutions to render complex Kanji characters. Check out this screenshot comparing Sierra's The Dark Crystal and Enix's Zarth to see how advanced Japanese PCs were when it came to graphics.

Depending on who you talk to, the accolade of "First JRPG" is contentious and, sadly, most of these games are lost or unplayable. Koei's Underground Exploration and Spy Daisakusen are often credited as the first, since both released in the early spring of 1982. The problem is that the familiar DNA of roleplaying is almost non-existent. Spy Daisakusen, which is the Japanese title for Mission: Impossible, is a rare kind of proto-RPG that abandoned the popular medieval aesthetic for a theme of modern espionage. The first mission is delivered via a tape recorder and your character has a randomly assigned set of stats that can only be changed by resetting the computer. Similarly, Seduction of the Condominium Wives, a third proto-JRPG, quantifies your character's abilities using various stats like virility and intelligence governing how successful your are at selling condoms or seducing women.

A far better contender for the first proper JRPG would be The Dragon and Princess, another early Koei RPG released in December of 1982. In Dragon and Princess, the first tenets of JRPG design emerge as players control a party of five heroes setting out to reclaim a treasure stolen from their king. The Dragon and Princess was divided into two modes: a text-based adventure mode and a top-down strategic battle mode—one of the first implementations of tactical turn-based combat in an RPG that predates its more recognized implementation in Ultima 3: Exodus.

Back then, Japanese people didn't have a well-defined sense of the RPG as a game genre.

Tokohiro Naito

Despite core RPG concepts being present in The Dragon and Princess, you'd hardly want to go back and play it. According to Derboo at Hardcore Gaming 101, the game is unplayable and horribly balanced. "The tactical options are severely limited and the game suffers from Final Fantasy 1 syndrome, with characters and enemies alike fumbling most of their attacks, drawing out even the most small-scale battles," they write.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Still, these games are crucial to the history of Japanese computer RPGs. They were crude first attempts at carving out a template that later games would build off of. As Tokohiro Naito, designer of the seminal JRPG Hydlide, said in The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 2: "Back then, Japanese people didn't have a well-defined sense of the RPG as a game genre. I suspect that because of this, the creators took the appearance and atmosphere of the RPG as a basic reference, and constructed new types of games according to their own individual sensibilities."

Leading up to the renaissance

Though the Japanese RPG scene got off to a rough start, by 1983 Koei and other companies were releasing games that had a much clearer vision for roleplaying. Dungeon, for example, was a first-person dungeon crawler that demonstrated how big of an impact games like Wizardry and Ultima were having in Japan. Many of Dungeon's monsters were clearly stolen directly from the Dungeons and Dragons rule books. While you don't manage an entire party in Dungeon, you can build your character by choosing one of five archetypal classes—like wizard or warrior—and explore an island in search of the treasure of El Dorado. Dungeon offers little in terms of innovation outside of its single dungeon that measures a massive 250 by 250 squares.

It wasn't until January of 1984 that Japan would see its first RPG hit. Despite two years worth of releases, RPGs still were little more than a niche genre for only the most hardcore Japanese PC gamers and programmers. Ironically, the person to change all of that wouldn't even be a Japanese.

In the late '70s, Amsterdam-born Henk Rogers abandoned his studies in Hawaii and "chased a girl to Tokyo," getting a job with her parents' gem company to cover room and board. Unable to speak Japanese and working just to keep a roof over his head, Rogers was astounded to discover how little Dungeons and Dragons had penetrated mainstream Japanese culture. Back in Hawaii, the tabletop RPG dominated every waking moment of his life. In 1982, he became obsessed with the idea of programming his own RPG tailored to Japanese players.

Forget gigahertz or DDR5 ram, the PC-8801 became Japan's de facto gaming PC thanks to these killer specs. Later versions added more VRAM for higher color depth and a Yamaha sound chip.

CPU: NEC µPD780 4 MHz

RAM: 64KB

VRAM: 48KB

Resolution: 640 × 200 with 8 colors or 640 × 400 with 2 colors

"It was immediately obvious to me that the core difference between the two markets was that there were no computer role-playing games in Japan," he said in an interview with The Magazine. Despite Koei pumping out proto-RPGs for years, Rogers felt like they still hadn't penetrated Japanese culture to the same extent as in North America—and he saw an opportunity. "The US had Ultima and Wizardry. But there were no such adventures in Japan. I thought, I could do that."

After saving up $10,000 for a PC-8801, Rogers began working on a game that he hoped would finally bring RPGs to the forefront of Japanese videogame culture. The Black Onyx relied heavily on the first-person dungeon crawling aspects of Wizardry but brought several innovations to the genre including character appearance customization, representing health as a colored bar, and being able to recruit NPCs to fill out your five-man party.

The release was a disaster. The Black Onyx relied too heavily on Western fantasy aesthetics in its marketing, and Rogers explained that it didn't resonate with Japanese gamers. In the first two months, The Black Onyx only sold five copies. That's when Rogers decided to hire a translator and visit every major Japanese PC magazine and demo the game in-person. "I sat down with each editor and asked them for their name," Rogers explained. "I typed this in and then asked them to choose the head that looked most like them. In this way I taught them how to roll a D&D character. Then I left them to play.”

Astounded by the idea of creating their own character, every magazine Rogers visited ran extensive coverage of the game in their next issue. That month The Black Onyx sold 10,000 copies and continued to do so until it became the best-selling Japanese videogame a year later with 150,000 copies sold. Finally, RPGs had become mainstream in Japan.

The US had Ultima and Wizardry. But there were no such adventures in Japan. I thought, I could do that.

Henk Rogers

At the same time, the native Japanese developers were still pushing their own vision of the genre forward. In June of 1894, Namco released the arcade game The Tower of Druaga. Despite not really being an RPG in its own right, Druaga inspired two games that would go on to cement the action-RPG subgenre in Japan. In Dragon Slayer, players explored dungeons from a top-down perspective while battling monsters in real-time despite still using character stats. Puzzles required specific items to solve, but players could only hold one item at a time. In many ways, Dragon Slayer laid the foundation for games like Legend of Zelda and Ys. Later iterations would eventually spawn the popular offshoot JRPG series Legend of Heroes: Trails in the Sky.

Hydlide was similar to Dragon Slayer, but creator Tokohiro Naito is credited with inventing the idea that standing still slowly regenerates health and mana—a concept that would later be stolen by the creators of Ys. Independent of The Black Onyx's success, Dragon Slayer and Hydlide would go on to become massive in their own right. Dragon Slayer spawned over 60 sequels and spin-offs, while Hydlide received several sequels and reportedly sold two million copies across its lifetime.

The designers of Hydlide and Dragon Slayer had a years-long friendly rivalry with one that played out in hilarious ways. In Dragon Slayer's sequel, Xanadu, making your character's name 'Hydlide' would give them the worst possible roll on all of their stats, for example.

But until now, every major Japanese RPG still bore a striking resemblance to their western counterparts—either intentional or accidental. To understand how the genre began to step into the unique anime-inspired aesthetic that defines its biggest series like Dragon Quest, we have to look into the history of Enix, the company that created it.

The Enix Game Hobby Program Contest

Like most Japanese software companies, Enix started in a completely different industry. Originally a real estate tabloid publishing company called the Eidansha Boshu Service Center, Enix rebranded in 1982 after a failed attempt to take its publishing business nationwide. The name Enix is a play on words, combining the mythological phoenix with ENIAC, the name for the first digital computer ever built.

Spending time abroad, founder Yasuhrio Fukushima saw the potential in videogame development and wanted to get in on the action but had one problem: He didn't know any professional programmers. His answer came from the manga industry, which frequently held contests where aspiring writers and artists could submit their stories and art in hopes of being published. In fact, seminal manga creator Akira Toriyama of Dragon Ball fame got his start by entering a contest held by Jump magazine.

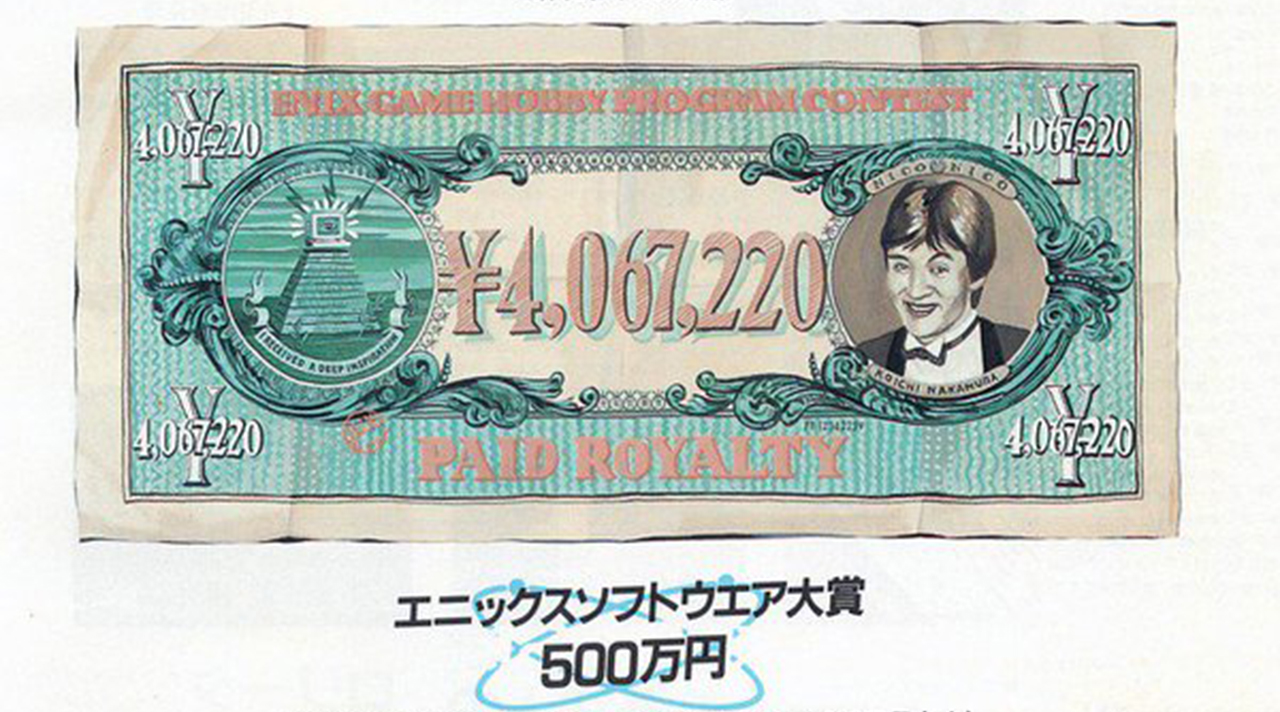

Enix borrowed the approach and in 1982 held the Enix Game Hobby Program Contest offering a one million yen prize to the top three contestants in addition to royalties that they would earn once Enix published their games.

"It was this idea that started to lead Japanese RPG design down a separate path from that of the Americans," explains Roo in his YouTube series on the rise of the RPG. As Roo notes, Enix didn't just advertise their competition in computer gaming magazines, but also in manga publications as well. "As a result, when American game companies at the time were generally formed around computer hobbyists, Enix hired and was influenced by manga enthusiasts."

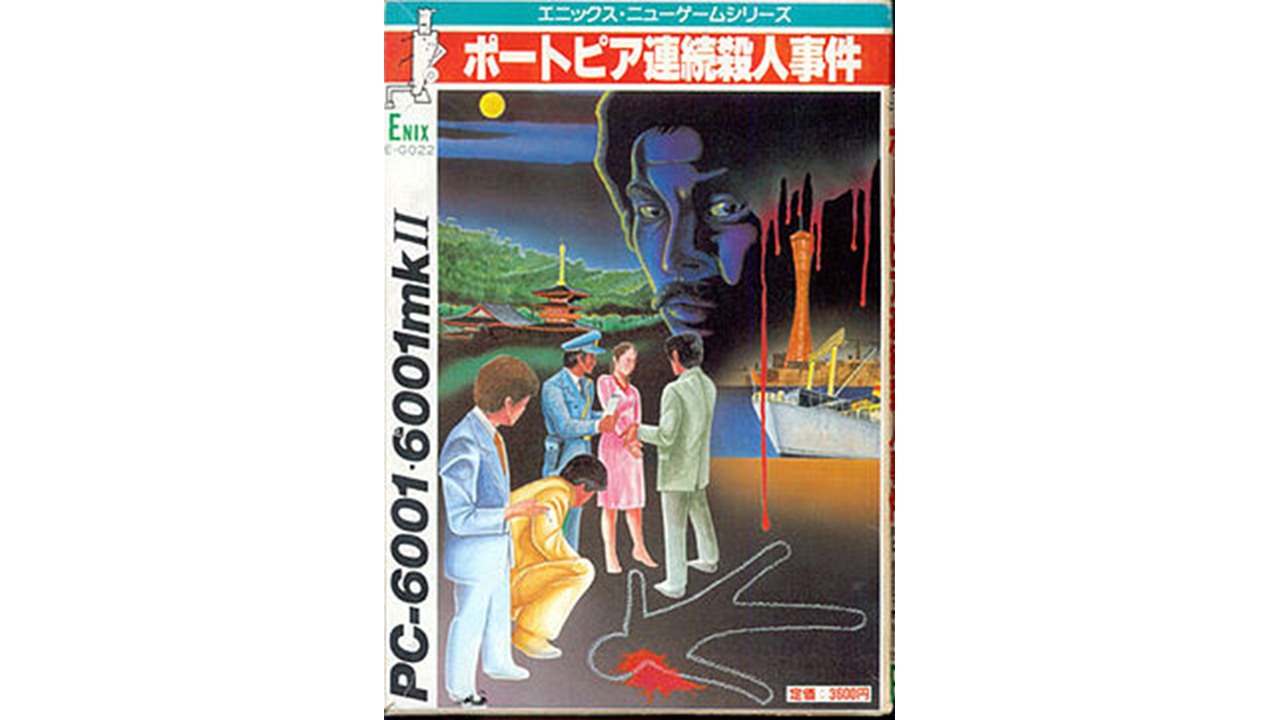

Of the three hundred submissions to the Enix Game Hobby Contest, one of the three winners was Yuji Horii, who was also a freelance writer for Shonen Jump, a very popular weekly manga magazine. Enix turned these products into its first published games, and a year later Horii made waves in Japan with the release of his adventure game The Portopia Serial Murder Case which was originally released on the NEC PC-6001 and ported to other PCs and consoles years later.

Portopia Serial Murder Case was a dramatic step forward for adventure games and visual novels in Japan. Some of its biggest innovations to the genre included a non-linear story set in an open world where players would converse with NPCs using branching dialogue options. While not an RPG, Portopia Serial Murder Case still had a big impact on JRPG design because it became one of the major inspirations in Horii's next game, Dragon Quest—the game that would change the definition of JRPG forever. Tangentially, Portopia also inspired Hideo Kojima to start designing videogames.

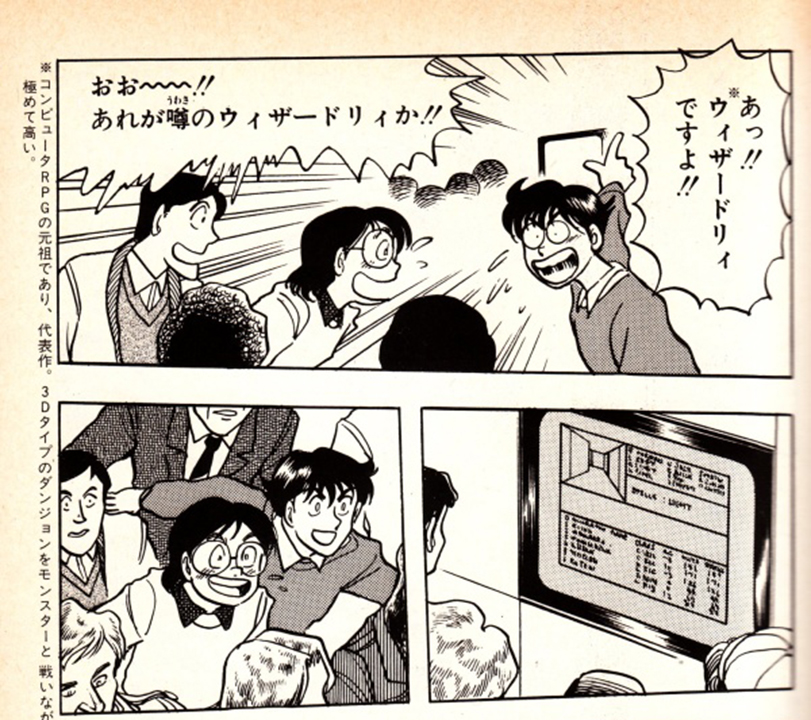

By 1985, these disparate elements of Western-inspired RPGs and Horii's own take on adventure games would intersect. As part of winning the Enix contest, Horii was sent to the 1983 Applefest in San Francisco, where both he and fellow Enix contest winner Koichi Nakamura first saw Wizardry running on an Apple II. Woodhead's computerized version of Dungeons and Dragons left Horii and Nakamura awestruck and the two became obsessed with RPGs upon returning to Japan.

Over time, Horii began to gravitate towards Ultima-inspired RPGs with their emphasis on exploration, while Nakamura remained obsessed with Wizardry and its menu-based combat. When Horii insisted the two begin working on a new type of RPG together, they decided to combine the best of each game along with Portopia's heavy emphasis on storytelling (at least, in the context of game storytelling at the time) and the result was the RPG that would finally set Japan on course to rival the West's mastery of the genre: Dragon Quest. When Dragon Ball artist Akira Toriyama was signed on to design the manga-inspired character art, the template for all Japanese roleplaying games going forward was established.

But Dragon Quest never released on personal computers. Instead, Horii and Nakamura designed it to be played on Nintendo's Famicom. And as home consoles began to explode in popularity both in Japan and the US, the cultural significance of Japanese computer gaming began to decline—despite continuing for years, eventually circling back around with the popularity of software like RPG Maker.

But while Japanese computer RPGs might feel like a tiny footnote compared to the greater legacy of Dragon Quest and, soon after, Final Fantasy, they are an important part of what makes golden-era JRPGs great. Whether it's subtle technical differences like the PC-8801's higher screen resolution allowing for more visual flair or the way early Japanese developers experimented with basic RPG ingredients, each small step played an important role in defining Japanese roleplaying games for generations after.

This article could not have been possible without the work done by Hardcore Gaming 101 and game preservationists like John Szczepaniak and Felipe Pepe.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.