The evolution of The Elder Scrolls

How The Elder Scrolls series went from gladiators to Dragonborn.

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011)

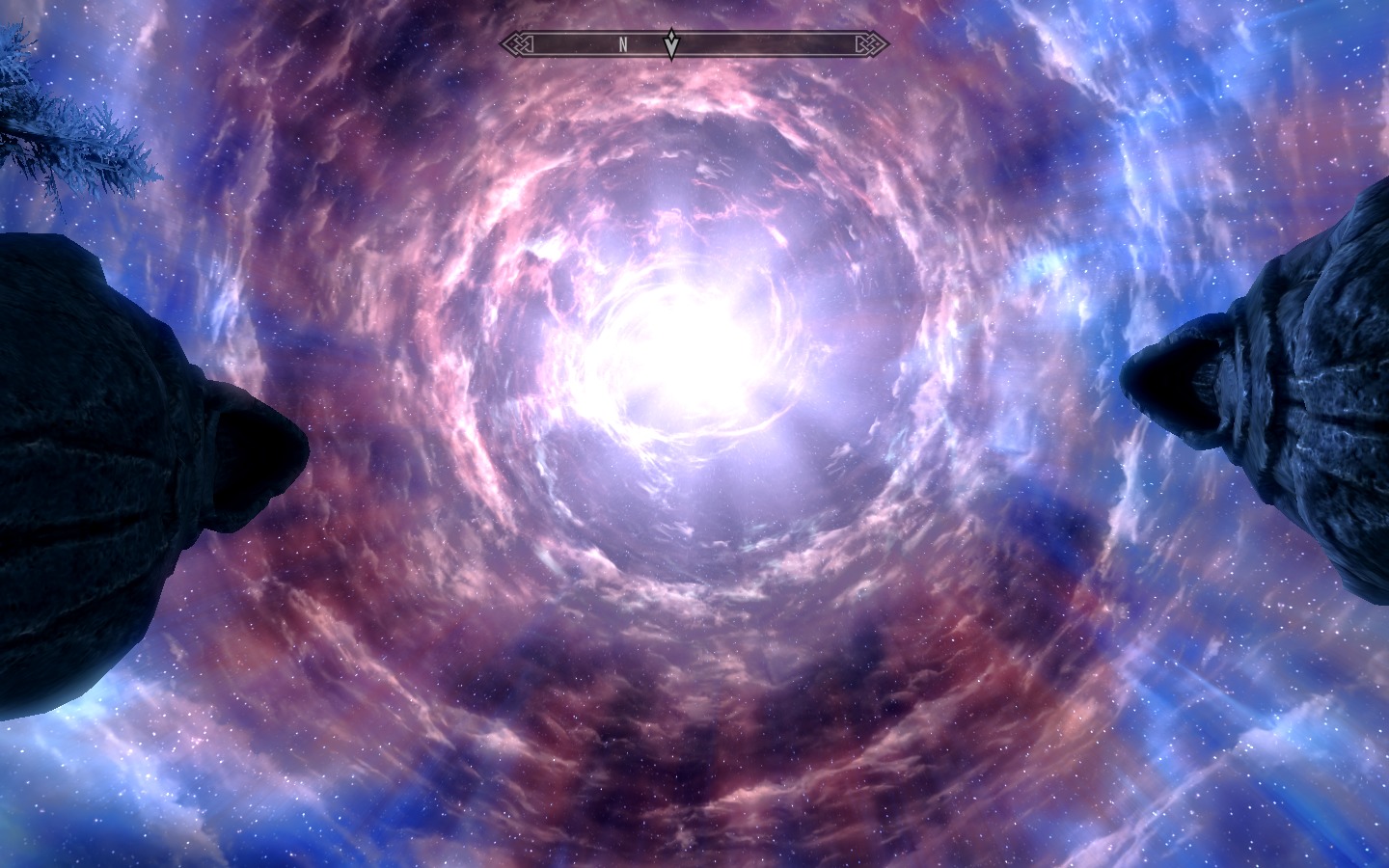

Depending how you measure it, Skyrim’s map may be slightly smaller than Oblivion’s. It’s much less flat, however, and there’s a lot of geography outside the bounds of the game, only visible from the top of its tallest mountain on a clear day or during the quest in which the player is summoned into the sky to commune with a god. That it contains climbing mountains and chatting with gods are part of Skyrim’s commitment to making everything feel epic. The main quest is the focus again, and the player is restored to the center of the plot—born a chosen one, with powers beyond those of mortals and a destiny to fulfill. Unlike Oblivion, Skyrim’s most impressive set pieces all take place during its main quests, whether battling dragons or traveling to the land of the dead.

Some of Skyrim's changes can be seen in user-made mods for Oblivion. Popular mods that added more combat moves were mimicked in Skyrim’s system of perks, unlocking new abilities with each level that made its combat more interesting the longer you played. An individual mod that sped up the rate arrows flew in Oblivion, which made a surprising difference to how enjoyable they were to shoot, was replicated for the archery in Skyrim. Other aspects seemed designed with gaps for modders to fill deliberately left in them, like the crafting and detailed weather and wildlife systems that seemed to beg for survival mechanics to be bolted onto them, as they inevitably were.

Way back in Daggerfall players had been given the option to create their own class, and Morrowind removed limitations on which classes could use certain equipment or learn spells. Skyrim took away the concept of classes completely, with starting skills determined purely by choice of race. Any skill could be used by any character, essentially leaving you to create your own class as you played, turning the entire game into one of the earlier entries’ Q&A sessions about what kind of adventurer you are.

Also removed was the ability to create your own spells. As far back as Arena, the Elder Scrolls games had let spellcasting characters edit spell effects and in doing so give themselves game-breaking magical powers, whether to knock down walls, fly, or become invincible. Skyrim’s crafting remained open to abuse, however, through tricks like making potions that temporarily increased your skill at creating enchanted items, which allowed you to make equipment that boosted your ability to brew potions—a loop that ended with low-level characters able to craft some of the best gear in the game.

That crafting system is a rare example of outside influence on an Elder Scrolls game. While first-person RPGs Ultima Underworld and Legends Of Valour have been cited as inspirations for Arena, and apparently the addition of vampires came after the team played the tabletop RPG Vampire: The Masquerade, the Elder Scrolls games have largely done their own thing. They’ve become influential, but only rarely been influenced. That changed when Skyrim not only added crafting but companions and romance options—rudimentary ones, but still. It’s an example of a willingness to borrow from other RPGs that’s new.

Of course, Skyrim was also influenced by lessons Bethesda learnt while working on Fallout 3 between Elder Scrolls games. It and Skyrim share the same level-scaling mechanic, which balances each area to be a challenge for players when they first arrive in them, but then keeps them at that level of danger, making the areas first visited less of a threat when returned to later. Another idea from the same source was giving NPCs unique conversations rather than mixing their personal dialogue with a generic pool of rumors and observations that sometimes jarred. Skyrim’s random narrative encounters, like the thief who hands you a weapon moments before the hunter he stole it from arrives, also came from Fallout 3. “We realised in Fallout 3 that that kind of environmental storytelling, where you come upon a little scene, is really good,” Todd Howard explained. “And so we’ve tried to do it a lot more.”

Unlike each sequel in the Elder Scrolls series, Skyrim Special Edition doesn't significantly build on what came before. It's the same Skyrim, but with improved lighting, inferior audio and the potential for more and better mods thanks to a 64-bit executable. With Bethesda saying The Elder Scrolls VI is still a long ways off, Skyrim Special Edition will likely be a canvas for modders for years to come.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

With Fallout 4, Bethesda took even more influence from other RPGs, namely by adding a voiced protagonist, and has also given a nod to building games with settlement construction. It seems natural that the lessons Bethesda learns from these changes, positive or negative, will also make their way into the next Elder Scrolls, along with lessons from Skyrim and its predecessors—although it’s probably not going to bring back the game-breaking spellcrafting system. More's the pity.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.