The evolution of loot boxes

How today's loot boxes arrived in games, from 1800s cigarette pack-ins to a 2006 Chinese MMO to the hats of TF2.

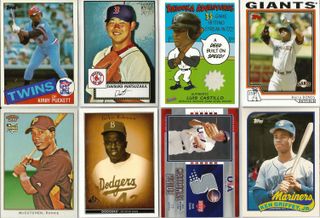

It might be hard to imagine now, but in the early ‘90s, baseball cards were a big deal. A really big deal: as the collecting frenzy boomed, the baseball card industry raked in well over a billion dollars a year as collectors bought piles of packs hoping to score rare, limited edition cards. Today, after decades of oversaturation, that number has fallen off, with sales now as "low" as around $200 million a year.

It feels like we’re on the threshold of a similar boom and bust in gaming. Five years ago, loot boxes, which contain a randomized selection of in-game items, were only in a few big PC games like FIFA and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. But this year alone we’ve had half a dozen major franchises take the plunge, with Call of Duty, Battlefront, and Shadow of War leading the charge.

Videogame loot boxes can trace their origins back to decorative cards packed in with cigarettes more than a hundred years ago, but their recent history starts with the most popular collectible card game of all time, a sleazy Chinese MMO, and the powerful influence of Valve Software.

Analog origins

Puzzle & Dragons, a simple match-three game, earned more than $1 billion in revenue in a year.

Loot boxes are a relatively recent development in multiplayer games, but anyone who has ever played a collectible card game like Magic: The Gathering or Yu-Gi-Oh! know the random mechanism all too well. I can still recall hoarding those foil packs at my local big-box store, knowing that I was "guaranteed" at least one rare card, yet I always found myself hoping for an elusive holographic.

Magic was the first to take this collectable sports card model, with randomized card packs, and apply it to a game, and it found a ravenous audience, spawning legions of imitators and making ungodly amounts of money, with revenues for 2013 alone estimated at $250 million. In the 90s, everyone wanted to be like Magic, and for every success like Pokemon there were a dozen failures that tried to cash in, like the Mortal Kombat Kard Game.

More recent games like Android: Netrunner would remove the element of chance from their booster packs, but most trading card games remain irrevocably linked with random card packs, and players seem fine with it: millions more people play Magic: The Gathering now than they did in the 90s.

Whether the cards were used to play a game, such as with Pokemon cards, or were just for collecting like baseball cards, giving buyers a chance at scoring a rare card was a big controversy back in the 90s. In 1996, lawsuits brought against baseball card manufacturers alleged they constituted an illegal lottery, and in 1999 Nintendo was sued along the same lines for Pokemon cards. But for as big of a story as it was at the time, very little came of it.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The jump to games

Considering the popularity of TCGs, it’s somewhat surprising that it took more than a decade for an enterprising designer to deploy the concept in a videogame. RPGs were no stranger to random loot, of course, and early online games like Diablo, Everquest, and World of Warcraft helped codify many of the conventions still in use today, like colors denoting levels of rarity. In a sense, booster packs were just an analog solution to a problem that game designers could solve with a few lines of deft code. But that didn’t stop someone from trying to work card packs into a videogame.

Industry researchers identify Chinese free-to-play MMO ZT Online from 2006 as the pioneer. The book Red Wired: China's Internet Revolution cites ZT Online's innovations: "virtual treasure boxes, which may contain in-game items worth more than the cost of the box itself" and "allowing players to hire in-game 'substitute players' which let them raise their characters' experience levels without actually playing.'"

ZT Online’s take on the concept was even more vicious than the ones our Western triple-A overlords have cooked up in the years since—not only did it feature the now-canonical lock-and-key system made famous by Counter-Strike, but the game would show you all the loot that the chest could contain on a circle reminiscent of Wheel of Fortune. According to the Southern Weekly article that describes ZT: "Chests will frequently contain the high-class equipment that gamers desire, but the spinning light wheel always passes over them."

It wasn’t long before many of the popular games in Asia had adopted loot boxes or other pay-to-win microtransactions as a major source of revenue.

Mobile mutations

As the viability of the loot box became more apparent, clever game designers began to spin the concept in order to maximize profitability. Of these forks, the "gacha games" that emerged in the early 2010s in Japan proved to be the most durable, with developers replacing the now-familiar loot chest with the digital version of "gachapon," popular toy dispensers that spit out a random toy like a gumball machine when you insert a dollar or two.

Perhaps the best-known early gacha game is Puzzles & Dragons, from early 2012. Players would spin the crank on the virtual machine many times in the same way you might stock up on Overwatch crates, hoping to receive rare rewards from the random number goddess. Puzzle & Dragons, a simple match-three game, earned more than $1 billion in revenue in a year.

Some would even challenge players to complete sets of common items in order to trade in for a rare item, a design known as "complete gacha." As any statistician knows, at the start, you’re far more likely to fill out the constituent parts of the set. As you approach completion, however, your chances become far smaller, requiring more and more of your hard-earned cash to spin it out—essentially fooling your brain into thinking you’re oh so close to your goal, when in reality you’re at least twenty bucks away from that plush alligator decorating your virtual shelf.

Eventually, Japan found that this particular practice was in violation of an anti-gambling statute and banned it, though developers quickly cooked up alternatives to skirt the law.

Under lock and key

By the early 2010s, Western developers had noticed the blockbuster success of mobile and free-to-play games attached to social media—remember Farmville?—and they wanted a piece of the action. (It might seem ridiculous now, but back in 2011, Zynga reported Farmville revenues of over $250 million per quarter. That’s a lot of cows.) For these titans of industry, however, it wasn’t so much about creating new games to take advantage of these monetization strategies, but rather bolting them onto their mammoth properties, like FIFA or Counter-Strike.

When it came to the implementation of the loot box, not every developer was quite as gracious as Valve.

The first big Western game to incorporate loot boxes on a major scale was Team Fortress 2, which Valve turned into to a free-to-play shooter in late 2010. Players would earn crates through normal progression, which they could purchase "keys" to unlock, with a smorgasbord of possible rewards waiting just under the lid. (Like many "ethical" free-to-play games, all of the bounty offered by these crates could be grinded out through regular play—buying keys would merely speed up the process.)

When this approach proved profitable with the droves of players who descended upon the now-free game—Gabe Newell reported that the move multiplied the playerbase by a "factor of five"—Valve ported the concept to Counter-Strike: Global Offensive to rave reviews. In contrast to TF2, however, the loot offered in the CS crates were purely cosmetic—weapon skins that had no effect on how many shots your AWP would need to down that terrorist. And unlike many free-to-play games, Valve openly allowed players to trade their virtual gains for real money on the marketplace, allowing a lucky few to essentially trade virtual loot for real games.

Cosmetic and otherwise

When it came to the implementation of the loot box, not every developer was quite as gracious as Valve. 2007 console soccer game UEFA Champions League 2006-2007 was the first to apply the concept of trading cards to competitive sports. You build your team, including your coach and stadium, from an ever-growing stack of cards that you can grind out by playing game after game, or you can—you guessed it—speed up the process by paying real-world money for the card packs. EA saw this system in action and decided to add it to nearly every sports game they make: FIFA's card-based Ultimate Team mode showed up soon after, in 2009. Madden got it in 2010.

And while the concept of trading players like real coaches might sound enthralling—and the modes have certainly won a massive fanbase over the years—some users complain that the system is a classic example of a "money game" fooling players into thinking it’s a "skill game," with the top players shelling out wads of cash in order to keep their precious rank. EA is even applying the trading card concept to combat sports, with the upcoming UFC 3 featuring cards in the same Ultimate Team mode that give you not just specific fighters, but moves and even outright stat advantages. Imagine a Street Fighter where the other player’s Hadoken moves ever-so-slightly faster than yours because they spent five bucks on the game, and it’s easy to see why so many players choose to ignore Ultimate Team and stick with the other modes.

Before this year's Battlefront 2 controversy, EA had dabbled with microtransactions in its non-sports games with less explosive results. The card packs in Mass Effect 3 multiplayer in 2012 proved popular. Dead Space 3's, in 2013, not so much.

Towards a breaking point

In 2016 and 2017, Overwatch raked in cash by the truckful with its cosmetic loot boxes, with Blizzard reporting combined revenues from the game at over $1 billion by early 2017. The past two years have seen the prevalence of loot boxes swell as developers continue to try to find alternate ways to entice players into spending past the initial buy. Though many view Overwatch’s approach fundamentally ethical, the fact that you can only buy loot boxes and not the skins themselves with real currency arguably encourages the same sort of overconsumption as the "complete gacha."

Many viewed the introduction of "single-player loot boxes" in Monolith’s Shadow of War as a bright line—the first time loot boxes have actually applied to the single-player mode of a game that sells for $60. Items that boost progression in single-player games have now been around for years, but it's the inclusion of the random element that seems particular exploitative.

And now, after Star Wars: Battlefront 2 was assailed on all sides for attempting to loot boxify perks and stats, it seems that we’ve arrived at a reckoning. Until recently, gamers may have grumbled about the crates that have slowly taken over some of their favorite games, but enough indulged in the habit to keep corporate coffers full. With Battlefront 2, droves of players protested, and regulators began to grumble about the how the practice might meet the legal definition of gambling. Eventually, EA relented, removing microtransactions from the game, possibly permanently. But legislators continue to talk about the possibility of classifying loot boxes as gambling.

Despite the outcry over this year's singleplayer games, the popularity and profitability of loot boxes in multiplayer and gacha games likely means they aren't going anywhere. As for more meaningful loot—like a sharper sword or a stronger left-hook—the current climate shows that such power-ups are best kept siloed in separate modes, like FIFA’s Ultimate Team, far away from those who loudly detest them at every turn.

As long as there’s money to be made, developers will continue to fiddle with new mechanics to figure out how to get you to open your wallet. Then again, as regulators scrutinize loot boxes more closely than ever, and EA remains undecided on how to reintroduce Battlefront 2's microtransactions, if it does at all, this might be the turning point for one of gaming’s most controversial practices.

Lead video via Youtuber maxmoefoePokemon