The dangers of bad virtual reality

Oculus VR’s E3 booth stands two floors tall in E3’s West Hall, with a line snaking around one corner waiting to try on the near-final consumer Rift headset. Inside the booth, Oculus staff help usher press and game developers into into interviews and meetings and hands-on sessions, or hover near Oculus headsets and Touch controllers on display for passers-by to gawk at. It’s the kind of big, efficient production you’d expect from Oculus, with Facebook’s money behind it. Over the past three years, Oculus has become the most recognizable, most successful face of VR. And where there’s success, there’s imitation.

A handful of VR booths were clustered near Oculus at E3 2015, creating the impression of a promising VR quadrant at the show this year. “Look at all these virtual reality companies,” a savvy salesman would say. “They’re proof that VR is successful. It’s really happening!” Someone more cynical—someone like me—would say that these other VR experiences are not proof of VR’s success, but hangers-on trying to ride a tidal wave of positivity to riches and recognition.

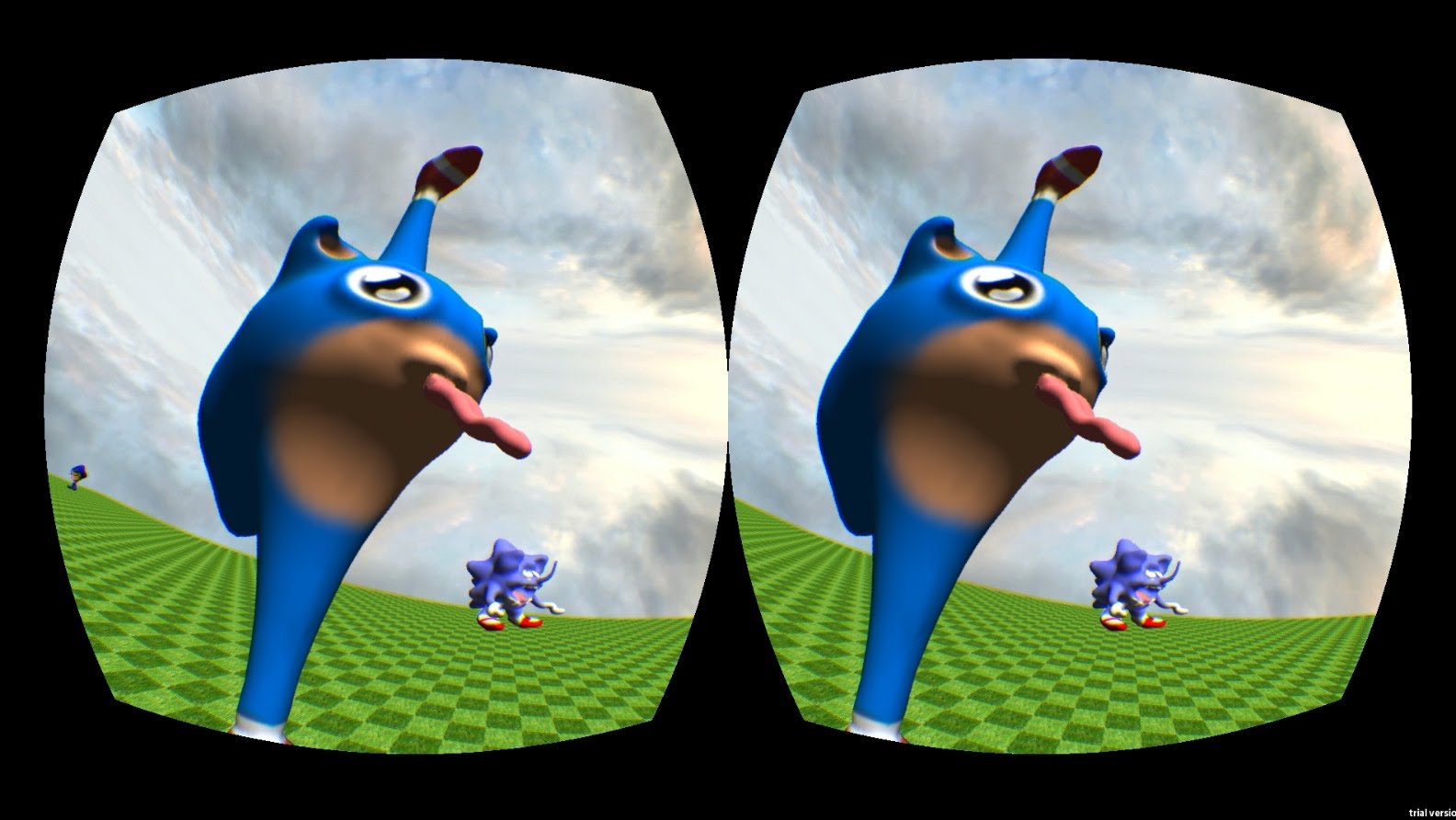

These second-tier VR companies and experiences are important, because trying them is a keen reminder of just how incredibly hard VR is to do right, and of the enormous engineering talent at Oculus and Valve making those experiences powerful, comfortable, and immersive. Trying on the consumer Oculus Rift will boggle your mind if you’ve never experienced VR before—but if you really want to be convinced, spend five minutes wearing a crappy VR headset immediately afterwards.

These second-tier VR companies are also dangerous, because not everyone knows the difference between good virtual reality and bad virtual reality. Not everyone gets to try on half a dozen different headsets and compare them. Not everyone reads about VR in detail online. If anything causes VR to be a disastrous mainstream failure, it will be these hangers-on, like the ones surrounding Oculus at E3. For the average person, all it will take is one terrible VR experience to assume that virtual reality in general is still just a crazy pipe dream. That it’s not actually awesome and compelling.

And these VR experiences truly are terrible. I knew they’d be terrible. But I decided I had to try one anyway, just to remind myself.

The nauseating AntVR

AntVR’s small booth sat right next to Oculus at the LA Convention Center’s West Hall. It was mostly open space, with a small platform and two swivel chairs serving as a pair of demo stations for the AntVR headset. I sat down and one of the AntVR staffers helped me put the headset on. Once it was on my face, I knew things were about to go south in a hurry.

The headset was heavy. Wearing it for even 15 minutes would put serious strain on your neck and head, and would probably cause headaches by itself. Paired with the display’s visibly low refresh rate, which was at best 60Hz, and the lack of head tracking, which left all movement sensing to the gyroscope, accelerometer and magnetometer, 15 minutes with the AntVR would be enough to leave just about anyone nauseous, headachey, and probably in need of a second lunch.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Because it’ll definitely make you puke.

AntVR, which was Kickstarter in 2014 for $260,000, had more problems that are immediately obvious if you’ve used other VR headsets. The display was large, and AntVR’s spec sheet says 1080p per eye, but its lenses weren’t designed to make that display comfortable or practical for your eyes. It was like slapping a giant square screen in front of your face and saying "there, now it's virtual reality!" The optics did, at least, allow my eyes to focus on the screen, but the experience was more like staring at a pair of smartphone screens shoehorned into a heavy plastic housing than anything remotely immersive.

The software demo was also bad. It was a first-person shooter, and AntVR has designed a small gun-shaped controller for it, with an analog stick where your thumb rests and a trigger where you’d expect it. The analog stick was for moving your character, while aiming the gun did aim on screen. But moving your head was used for orientation, and without good head tracking, it was awkward, sluggish and frustrating to try to turn, walk, and aim. Hence the swivel chair.

Also, despite the headset seemingly being on my head correctly, the whole thing was tilted at a bit of an angle. I stumbled around the FPS environment for about five minutes, feeling a wave of motion sickness hit me every time I slowly rotated 90 degrees to make a turn, and then I’d had enough.

The VR “Experience”

Using AntVR’s headset, even for a couple minutes, crystallized Oculus’ mantra of virtual reality as an “experience.” As Oculus’ technology has gotten more and more advanced, the company has moved away from talking about hardware specs. They don’t like to talk about resolution or the exact technology of their screens or give out precise numbers for those things.

And yeah, some of that is PR and protecting their corporate secrets—it makes sense for Oculus not to give away the secret sauce. But they’ve also figured out that specs don’t tell the story of VR. AntVR’s 1080p per eye screen may be similar to the Oculus Rift, but the experience of using them is vastly different. Sometimes numbers do lie.

There are so many other things Oculus and SteamVR do right that contribute to the experience of VR, but they’re hard to fully appreciate until you compare them to a crappier VR headset. Weight makes an enormous difference. The way the headset straps to your face is important. Tiny and not-so-tiny differences in head tracking latency, screen refresh, optics can separate good VR from a vomit-fest, and it’s impossible to understand any of those from a spec sheet.

Software is just as critical: Oculus is making a point of flagging games with “locomotion” in their Oculus Home store, identifying experiences that will move you around a virtual environment even when your head isn’t physically moving, as that’s the primary cause of VR motion sickness. Game developers have to be very careful about how they implement cameras and movement in VR to keep the experience comfortable for players.

Unfortunately, most second-tier VR companies use their own software to try to show off the features that make their hardware a special experience. Or they use hacked-together VR versions of games that never should’ve been played in VR to begin with. Their custom software is usually terrible. Either approach is likely to create a bad VR experience, where motion sickness hits fast and hard.

The PC is an open platform, and without that openness we’d never see great VR like the Oculus Rift break onto the scene. That’s crucial, and it’s great for competition—nothing will drive Valve and Oculus to innovate more than what the other company is secretly cooking up. But as VR approaches its first real consumer roll-out, bad VR hardware from companies seeking to cash in can only harm its potential for success. It’s up to us—all of us interested in and excited for virtual reality—to prevent that from happening, by helping people experience and understand good VR.

I don’t think that’s going to be too difficult, because once you’ve used what Oculus and Valve have cooking up, it’s hard not to be excited for the next few years of gaming.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).