The complete history of Blizzard games on PC

We look back at the impact of every Blizzard game and share inside stories from veteran developers.

Page 1: The Lost Vikings - Warcraft 2 (1992 - 1995)

Page 2: Diablo - Warcraft 3 (1996 - 2002)

Page 3: World of Warcraft - Overwatch (2004 - 2016)

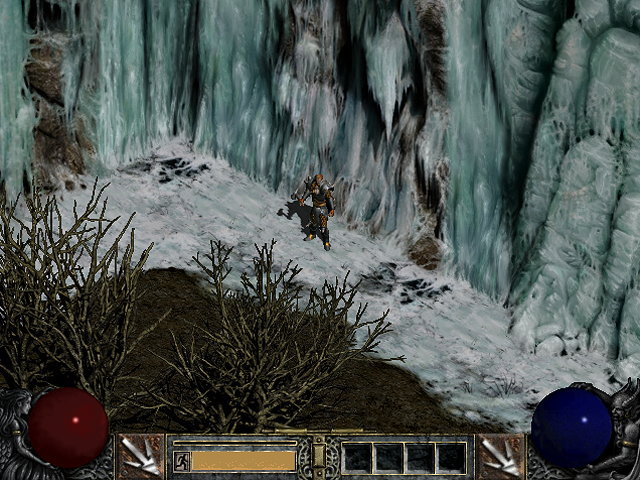

Diablo (1996)

Ahh...fresh meat

System requirements: Windows 95, 60 MHz Intel Pentium CPU, 16MB RAM for multiplayer, SuperVGA w/ DirectX 3.0

Diablo was originally going to be a turn-based RPG, and still sort of is: As designer David Brevik recounts below, when the decision was made to switch to real-time combat against his will, he begrudgingly did so by making turns happen 20 times per second. The Diablo-style action RPG was born from a vote and a quick hack, and though we’ll never really know, that likely turned it into the smash hit it was.

The original Diablo pitch from Brevik and his studio Condor—which would become Blizzard North before Diablo released—also included $5 point-of-purchase expansion discs which would add new items, monsters, and level elements into the mix. Essentially, they would have been digital trading card packs, an idea well ahead of its time in the mid-90s, and something Blizzard clearly embraces today.

While that idea was scrapped—Diablo only got one expansion, Hellfire—the game was a critical and commercial success. And outside of the slightly cheerier Diablo 3 artwork, the series hasn’t strayed much from what Diablo established: dark, gothic art, point-and-click combat, hotkeys, randomized loot, and randomly-generated dungeons. The first Diablo also brought about the advent of Battle.net—which originally ran on a single PC—and marked the beginning of Blizzard’s long battle with cheaters. With Diablo 2, it ditched peer-to-peer multiplayer for client-server multiplayer for that reason.

Collin Murray, lead software engineer at Blizzard, when asked if there are any secrets left undiscovered in Diablo

"There's an invisible armor rack on a certain level. I worked on the sprite rendering for the characters in Diablo 1. Occasionally they would pass us a null artwork pointer, and all I could do was not draw it, because I had no idea what the artwork was supposed to be. It usually manifested as an armor rack. It was clickable, but you couldn't see it because it had nothing to draw. So there's an invisible armor rack occasionally on certain levels, so you might accidentally click on it, and then it will look like a weapon will fly out of nowhere. I don't think we ever fixed it, either."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Shane Dabiri, 22 year Blizzard veteran and current Chief of Staff

"Prior to Diablo we were working on a game called Death & Return of Superman. We were contracted by DC to do the Super Nintendo version while another company named Condor was contracted to do the Genesis version. Since we were both working on basically the same game, a fighter with all the DC superheroes, we ended up collaborating with them… and we got to know them pretty well. After that project ended we kind of hit it off and they had a pitch for something they wanted to do. It was this Rogue-like game. It was basically a dungeon crawl game, but it was turn-based, and they wanted the art style to be around clay animation. That was the original pitch for Diablo. When we ended up talking with them about it, we encouraged them to make a few changes, and some of those changes they thought were great, which was adding multiplayer and making it real-time instead of turn based, and the graphics we ended up making a little darker, the way Diablo ended up being.

"Condor [which became Blizzard North] was doing console development, so this was their first PC game. As a result of that they had to learn a lot of things as well. One of the things they had to do was figure out how they could work with a testing team to actually evaluate all of the random dungeons and random items that appeared in the game. In those early days we actually had no tools to do that. So if we wanted to test, say, one of the shrines or a certain weapon, we just had to play the game over and over and restart until that random seed came up again, which was very challenging. We didn't have any tools to spawn these things in. That didn't happen until much later, when we started working on Diablo 2, that they actually put all those in."

David Brevik, former president of Blizzard North, Diablo senior designer, in a GDC 2016 post-mortem

"When we pitched the guys at Blizzard Entertainment on making this game, they said this game is awesome, it looks great, it's such a great idea, but there's two things wrong. One, it's turn-based. Two, it needs to be multiplayer. They got their way on both. It was turn-based but the turns were divided into sections, so not everything was an even amount of turn length… We set up the whole game to have this kind of detail of how much time different skills took, stuff like that. It was kind of a complicated turn-based game. Eventually Blizzard South approached us and said, ‘We’d really like to make this a real-time game.’ And I said, ‘What are you guys talking about? Real-time? No, no, no, no, this isn’t one of your strategy games…' I'm really committed to making a turn-based game here... I really loved that tension, the sweaty palms, and I really didn't want to lose that at all. And they said 'Yeah, but real-time will be better.' Well, OK, if you so say. So they started going around, talking to other people in the studio, and they said 'yeah, we should make this real time!' There were two or three of us who held out to the bitter end. One day we decided to bring it to a vote and I voted no and everybody else voted yes. So I said okay, I guess we can do this. I called up Blizzard South and said 'this is a huge delay in the project, it's going to take us a long time, we have to redo all sorts of things, it's going to take me forever to write this, we need another milestone payment out of this but we'll go ahead and do it.' They agreed to this, so I sat down on a Friday afternoon and in a few hours I had it running.

"I can remember the moment that this happened. Like it was yesterday. This is one of the most vivid moments of my career. I just made the turns happen 20 times a second, or whatever it was, and it all just kind of worked, magically. I remember taking the mouse. I clicked on the mouse, and the warrior walked over and smacked the skeleton down. And I was like, ‘Oh my god! ...That was awesome!’ And the sun shone through the window, and god passed by, and the angels sung and sure enough, that was when the ARPG was kinda born, at that moment. And I was lucky enough to be there, it was an amazing, amazing moment, I’ll never forget it. That was a big turning point in the project. It was pretty early on, five months or six months in, that we had done this."

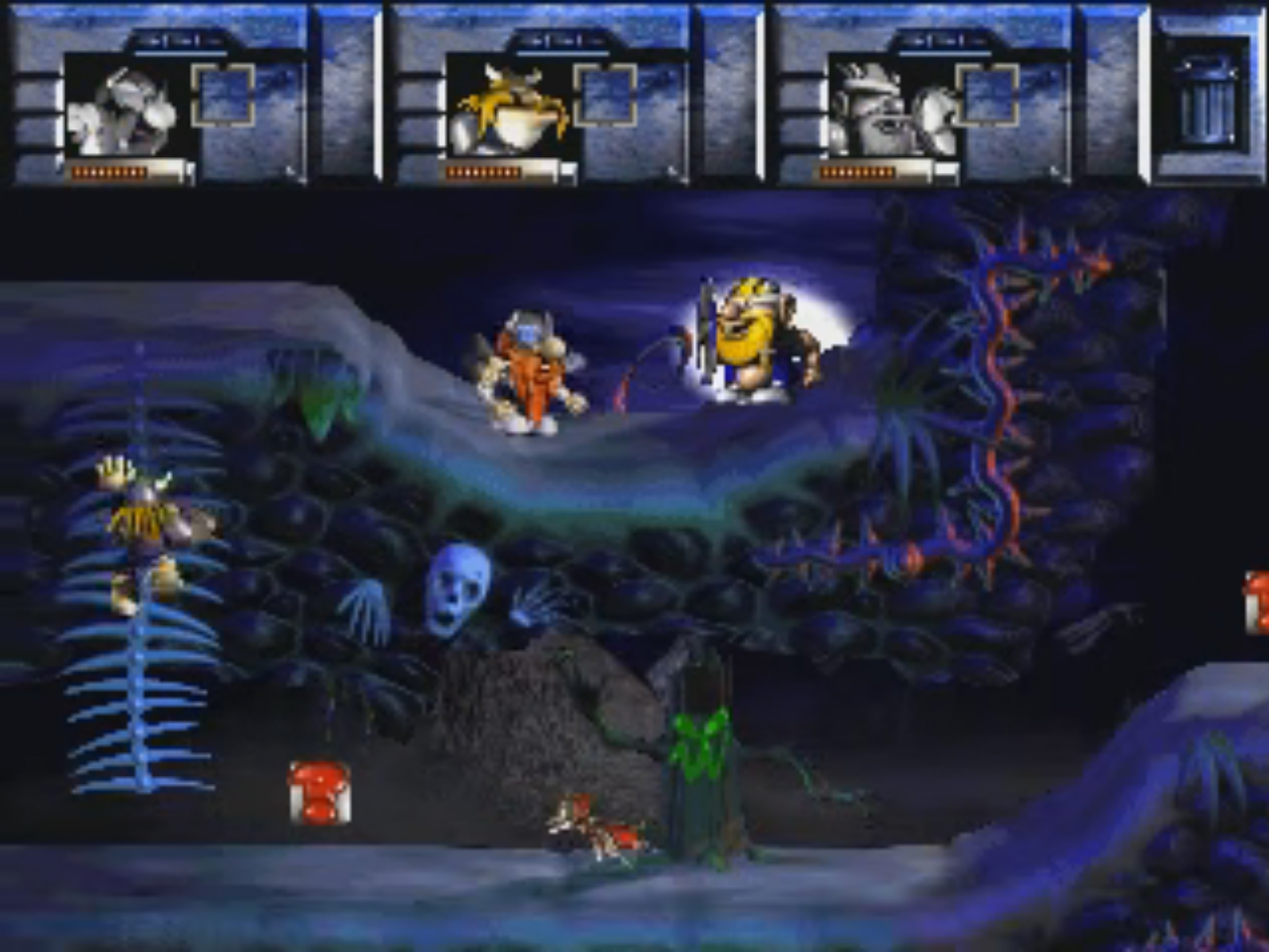

The Lost Vikings 2, aka Norse By Norsewest: The Return of the Lost Vikings (1997)

The boys are back in town...with a werewolf

System requirements: DOS 5.0/Windows 95, Intel 80486DX4 or 60 MHz Pentium CPU, 16MB RAM

The Lost Vikings 2 is remembered primarily as a Super Nintendo game, despite coming out for the system while the N64 had already been out for year. Blizzard developed the SNES version in-house, but the job of developing it for PC (along with Sega Saturn and PlayStation) was done by an Australian studio named Beam Software. Where the sequel had pixel art similar to the original on SNES, Beam replaced it with more modern pre-rendered 3D graphics like the Donkey Kong Country games. The PC version also had a new soundtrack and voice acting.

The funny thing is, the updated graphics were probably cutting edge at the time, they hold up significantly worse in retrospect. Maybe it’s helped by the recent surge in popularity of pixel art games, but the original Lost Vikings’ art still looks good, if old school. But the PC sequel’s fancy new style looks downright ugly 20 years later.

This was the last platformer Blizzard ever made, and was the last game it made for consoles until Diablo 3's port more than 16 years later. Interestingly, it was also the last game the studio ever made that didn’t have an online multiplayer component of some kind. Blizzard had already made the first two Warcraft games, the first Diablo, and would release the first StarCraft less than a year later, so The Lost Vikings 2 was truly the last bastion of the old days of Blizzard.

While Blackthorne is a mostly forgotten blip in Blizzard's history, Lost Vikings 2 bears the distinction of being the only one we couldn't find any quotes about from Blizzard veterans, and it never came up in our dozen recent interviews with the company. In fact, Blizzard even completely left it off the official (otherwise very detailed) timeline. There may be Lost Vikings 2 stories out there, but they'll have to wait for another day.

StarCraft (1998)

No, it's not just orcs in space

System requirements: Windows 95, 90MHz Intel Pentium CPU, 16MB RAM, DirectX 2.0

Without StarCraft, esports as we know it today would not exist. Of course competitive gaming would've taken off eventually, but you can trace the thread of today's massive stadium-filling tournaments back to StarCraft and its expansion Brood War, which became South Korea's national pastime more than a decade ago and are still played online today—quite a feat for a 18-year-old game in a fading genre.

Originally meant to be a quick project in the Warcraft 2 engine, StarCraft ended up being a difficult development for Blizzard, delayed well past its intended launch. This was the beginning of Blizzard holding onto its games and refining them until they were just right, and the payoff was enormous. The game sold millions of copies, and after the struggle, Blizzard's developers came out emboldened with the experience required to ship immaculate games. Amazingly, Brood War came out in the same year as StarCraft, just eight months later. StarCraft and Brood War were significant steps forward for Blizzard in integrating story into their campaigns and increasing the variety of narrative-driven objectives, but it's the legacy of the insanely demanding multiplayer that's truly lasted.

Frank Pearce, CDO and co-founder, in Blizzard 20th anniversary video

"We had just taken the Warcraft 2 engine and created some new art, almost basically skinned Warcraft 2 for a science fiction theme. It turns out, at the time we were very proud of it, but by the time the end of the [E3] show rolled around, we were a little bit embarrassed."

Bob Fitch, lead programmer on StarCraft, in Blizzard 20th anniversary video

"I said all right, give me a couple weeks, a month, I'll do a whole new engine, and when I come out of the dark room I'll have a new engine and you can use that to make StarCraft. So that's what I did."

Mike Morhaime, CEO and co-founder of Blizzard, in 20th anniversary video

"For the team, the crunch lasted for about eight months. But honestly, I look back on it rather fondly. I have this feeling that that entire team was kind of in the zone. Really productive, really effective, doing a lot of great work, knowing we were working on something really important. It was just a really important project, something we could be proud of."

Bob Fitch, 22 year Blizzard veteran, most recently technical director for Hearthstone

"We had just done the fantasy side of fantasy sci-fi, so there were a lot of people, and I was included, who also wanted to get into a bigger variety of that sci-fi/fantasy stuff and do some science fiction. We had tons of ideas for what to do. We're very into popular culture, movies, TV shows, and lots of the ideas come out of all that. So we started writing down all these ideas we wanted to do. We'd sort of already done that with Warcraft, so now it was time to do it with some sci-fi stuff. We weren't thinking about anything other than doing what we enjoy, and if everybody else enjoys it too, awesome. But at the very least we want to make a great game that we enjoy. There was really no other thinking beyond that. Was there money involved? No, we had no concept of trying to make money off of it, or trying to target anything, really. Other than what are we going to have fun playing.

"I didn't know it at the time—I know it now, looking back years later—but there was a moment that I realized StarCraft was going to be successful. It was when I was working on it, had just worked more than 24 hours straight. That was another thing of life back then: we did a lot of long hours because we were young and wanted the best product we could get, and we didn't care about time because we were all invincible and never got sick or anything, right? So we just worked however long we wanted to in order to make it. At that time I had worked 30, maybe 40 straight hours, and I thought 'wow, look at how much time has gone by, I should go home and sleep, this is crazy.' It wasn't that anyone was making me do it, that was just the way I was. I wanted to make it perfect.

“So I was all done with my 30, 35 hour shift, and I said, 'before I go, let me just play the game.' And that's when, in hindsight, I realized that I knew it was going to be successful. After 35 hours working on it, the thing I wanted to do before I slept was to actually play it. And not only that, I had a hell of a fun time playing it. In fact, somebody walked by my door while I was in the middle of playing, and if they had taken a picture, I think you would've seen this cackling maniac face because I had this huge smile, was laughing at the screen, and now I know looking back, that's when I realized it was going to be super successful."

Diablo 2 (2000)

Stay awhile, and listen

System requirements: Windows 95, 233MHz Intel Pentium CPU, 64MB RAM for multiplayer, DirectX 6.1

With no official design document, Blizzard North “just started off making up new stuff” for Diablo 2, according to Erich Schaefer’s postmortem. Rather than one town and dungeon, Diablo 2 took place across four acts, from the original Tristram to Lut Gholein in the desert, Kurast in the jungle, and finally Hell. It was bigger, more complex, and better geared for co-op. Within a few weeks, over a million players flooded Diablo 2’s wastes and catacombs and online realms with the newly relaunched Battle.net.

Along with Warcraft 3, Diablo 2 helped define the culture of online gaming in the early 2000s, and set up Blizzard as an online-focused publisher four years before World of Warcraft. LAN play remained vital, but Battle.net was clearly the future.

Sadly, apart from the Lord of Destruction expansion pack, Diablo 2 would be Blizzard North’s last game. Though little has been said about it officially, Blizzard scrapped the studio’s vision for Diablo 3 and restarted work sometime in the mid-2000s. Blizzard North was closed in 2005.

David Brevik on coming up with the skill tree, via US Gamer’s oral history of Diablo 2

“I have no idea where I thought of that idea. I mean, again, I thought of it in the shower. But I don't know where it came from. It came from, I didn't like the way that we were, how we were going up levels and getting these skills, and it didn't feel like there was enough creativity or choice or things like that. We wanted to give people this sense of, "How do I choose how to play my character?" We had all of these skills, and it was kind of a mess, and there was all of these potential builds, how do we organize it in such a way that allows the people to easily identify?”

Shane Dabiri, lead tester on Diablo and current chief of staff at Blizzard, when asked how they tried to solve cheating in the first Diablo

"It was actually create the second game. From the first to the second game it was really an evolution and trying to change the server architecture so all the data was on the servers, so we were actually streaming you more than just the connection. It was less peer-to-peer, more client-server type architecture.

“There was also a separation we made. Back then you could play single-player, which was local data. And then we tried to implement server data for some of your multiplayer assets. But it didn't really take fruition, fully, until Diablo 2. I haven't had to talk about this stuff in so many years, and when I talk about it today it seems so 'yeah, of course! Everybody does this today.' But back then we were rubbing two sticks together to make fire. It was very unusual."

Shane Dabiri on the Chat gem

"Remember we used to have the Chat Gem in Battle.net? Inside of Battle.net there was actually a gem in the user interface and you could click on it and it would change colors and make a tick noise. For the longest time, all of these gamers out there would be clicking it and speculating on what this gem did. You'd click it and it would say "Chat Gem enabled," and click it again and it would say 'Chat Gem disabled.' Well, inevitably what the Chat Gem did, is it didn't really do anything, It was just sort of this fun thing in the interface that made all this speculation, the community would think 'oh, after you click it 666 times it makes some sort of special level appear, after you click it enough times it makes a certain sound, your character gets special items' or whatnot. But it was a pretty interesting social experiment to just try to see what the players would come up with."

Designer Erich Schafer on QA testing in his postmortem

“We found we could not play-balance the climactic fight against Diablo without actually playing the entire game up to that point, because we could not predict what kinds of equipment a character might have, or what path through the skill tree he or she may have followed. This meant 20 or 30 hours of play for all the different characters, with a good variety of skill sets and equipment for each.”

Designer Erich Schafer on the crunch in his postmortem

“The only major downside to Diablo 2's development was the inhuman amount of work it required. A yearlong crunch period puts a huge burden on people's relationships and quality of life. Our biggest challenge for the future is figuring out how to keep making giant games like Diablo II without burning out.”

Warcraft 3: Reign of Chaos (2002)

Today, the Horde. Tomorrow, the World.

System requirements: Windows 98, 400 MHz Intel Pentium 2 CPU, 128MB RAM, DirectX 8.1

Before there was Dota, there was Warcraft 3. This RTS may now be best remembered for spawning the tower defense genre and allowing MOBAs to flourish with Defense of the Ancients, thanks to its incredible mod scene, but it was a hell of a game in its own right. Blizzard made the transition to 3D look effortless and created some insanely gorgeous cinematics to go along with its most complex storytelling in a game up to that point. Game development is by nature an iterative medium, but more than any of its other sequels, Warcraft 3 feels like Blizzard putting all of its accumulated knowledge into confident practice.

The story weaves through multiple campaigns like StarCraft's and advances the notion of heroes with special abilities. The 3D engine helps pull storytelling back into the maps. Mission variety again builds on what they did with StarCraft, binding story and strategy more tightly together. Warcraft 3 managed to be Blizzard's biggest, broadest game, and yet execute on everything it set out to do. Much of that was due to its amazing scenario editor, which Blizzard used to develop the campaign and handed over to the mod community whole cloth. Blizzard was competing at a higher level than the rest of the RTS field in the early 2000s, and the new ideas like hero units Warcraft 3 integrated were so effective they quickly found their place in other games and genres.

Chris Metzen, former Blizzard Senior VP of story and franchise development, in 20th anniversary video :

"Around the time that we started jamming Warcraft 2, I remember feeling very intensely "wouldn't it be fun to blow this thing out, have multiple kingdoms and continents, more races involved, each with their own distinct flavor and history. Ultimately there were many years between Warcraft 2 and 3. We had cut our teeth on a few other game types and universes that allowed us to grow and get our storytelling values in line. So by the time Warcraft 3 really came about, we were ready to attack that thing. We knew who we were as artists, we knew who we were as storytellers. The ideas came much freeer and much clearer, and it definitely had heart."

Scott Mercer, 20 year Blizzard veteran, Principal Designer on Overwatch and game designer on Warcraft 2:

"Early on during Warcraft 3 development, there was even more focus on the lower unit counts and the heroes. The concept was running around in that party, where here's your hero and here's your footmen along with it. The gameplay was even more of that. And then we actually took it back to sort of this in-between state, where there was absolutely base building, this normal RTS sense of you start small, build up, go through a tech tree. But it was the heroes, and the fact that the heroes leveled and had items, there were all these RPG elements that got added to the RTS genre through Warcraft 3. That concept alone is what I think inspired DotA to do what they did.

"The level editor that the players ended up having was the exact same level editor we needed to create the campaign. When you talk about the Warcraft 3 level editor, you have to go back to the Warcraft 2 level editor. We made the campaign for Warcraft 2 with that editor. It was very limited in what you could do. I think most all of the maps ended with 'destroy all the enemy buildings.' Going forward with Starcraft, we improved the editor, added more ways for you to win, more things we could do. You saw that in the Starcraft campaign where there was a bit more variety in the types of missions that we had there, and that was due to the editor becoming more robust.

“And then going forward into War 3, in early development, we knew we needed to create an even better editor because Warcraft 2I was our first 3D game. We wanted to do all the in-game cinematics and storytelling within the game, so the editor had to be even more robust...We had to create the camera system. There were the in-game cinematics we had, usually at the beginnings and ends of missions, where there was a character interaction. We actually had to be able to place those cameras inside the game world. What the editor allowed us to do was move the map around, the view of what the player would see, and take snapshots and sort of create cameras out of that. It was that kind of camera control that I think a lot of people used in the mod community to create these modes of 'oh, here's these crazy RPGs that are like third-person over a character.' There were a lot of things we could do with that. But that was all going back to needing to make these in-game cinematics.

“A lot of the very important features that the Warcraft 3 editor got over time were things that we needed, that made our lives easier, making the game. Things like being able to create new units with, choosing a piece of art, assigning a bunch of stats to that, if we could do that in the editor, then designers could do that without having to go bug programmers to put in the game. The editor allowed us to be very nimble with our designs in the campaign and really allowed our programmers to work on bigger issues. The mod community basically took all that and ran with it.

"The scale [of the mod scene] absolutely took us by surprise… We couldn't have imagined those kinds of mods would end up existing. We were very excited about it. It jazzed us up. A lot of the ideas that came from the mod community were things that, when we worked on Frozen Throne, we integrated some of those. Like the very last mission of the Orc campaign in the expansion took a lot of its gameplay cues from the Aeon of Strife, Dota type games with waves crashing into each other.

“It was a super exciting time. We just tried to go in and play them occasionally and see what people wanted. And all through this we were getting feedback from these mapmakers saying 'Hey, could you fix this?' There were actually some bugs to fix, and new features they wanted. A lot of those features were things we were like 'yeah totally, if we give you those features, we get those features in our own work.' It was this wonderful time of the community feeding on our creativity, we were feeding on their creativity. And the Warcraft 3 editor was allowing all this to take place."

On the next page: World of Warcraft - Overwatch (2004 - 2016)

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).