Baldur's Gate made Dungeons & Dragons cool again

Looking back at a pivotal moment for computer RPGs, D&D, and a little company called BioWare.

It’s sometimes said that Baldur’s Gate made RPGs cool again. But it had plenty of competition for that honor. 1998 landed in the half of the decade that gave us Fallout, The Elder Scrolls, a glimpse of another world in Final Fantasy VII (even if the original PC port was one of the worst things you could inflict on your computer that wasn’t a virus), and saw Diablo hitting a level of success that continues echoing through the industry today.

BioWare was a little known company whose previous game, the mech simulator Shattered Steel, had come and gone with little fanfare

A better claim is that it made Dungeons & Dragons cool again—that is almost impossible to deny. It both put the series back on track on PC, and ensured that much of what followed continued to owe a debt to those halcyon days of tabletop dice rolling.

The irony is that while for the time, Baldur’s Gate felt streamlined and mainstream, going back to it now is to find a very fussy game indeed. Not only is it awash in terms like THAC0, the original version was so strict that it wouldn’t let you stay paused if you nipped into the inventory screen during combat. It wasn’t competing with today's RPGs, though. It was being compared to the likes of the famous Gold Box games in all their turn-based glory, and individual games aimed at fans not scared off by names like “Menzoberranzan.”

Next to those, the combined effect of Baldur's Gate's gorgeous backgrounds and magic effects and smooth interface was like being carried away on a beautiful stream… at least for a while.

It helped that Baldur’s Gate took the world by surprise. BioWare was a little known company whose previous game, the mech simulator Shattered Steel, had come and gone with little fanfare. Suddenly being faced with this gloriously beautiful, intricate, personality-filled adventure was… well, not a million miles from Peter Jackson going from Bad Taste to Lord of the Rings.

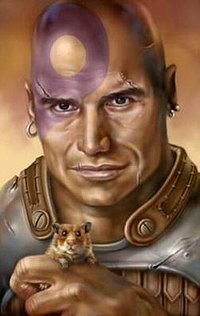

Almost immediately, characters like Minsc and his miniature giant space hamster Boo became gaming household names, while the chunk of the Forgotten Realms from Candlekeep to the titular Baldur’s Gate became home away from home for a good fifty hours or so of adventure.

Arguably the biggest individual success was the combat system, which moved away from the familiar scrum of both action-RPGs and the likes of Ultima, which weren’t particularly interested in that side of things. It also wasn't like the turn-based action of Fallout and pals: Baldur's Gate had a smooth real-time-with-pause system. This kept the action flowing fast and free, while still allowing for proper tactics.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

While technically everything was still being played out in rounds and with dice rolls, all of that was shoved under the surface to allow for action that felt far more visceral and freeform in 1998. Warriors charged into battle with their swords-and-boards ready, while casters hung back with spell and prayer books bursting with tactical options to help swing things one way or another. It was exactly what the genre needed at the time—the feel of D&D, with PC as an invisible dungeon master.

There were, of course, problems. This was BioWare’s first RPG, and even at the time, it showed. Most players soon hit a roadblock at the first major location outside the tutorial, the Friendly Arm Inn, where an assassin waited to bring the quest to a sudden end. This wasn’t necessarily a problem if you’d recruited some help earlier, but casters especially felt the sharp edge of starting out with barely enough HP to withstand a light wind. Later, the path through the game had a tendency to push unwary players too fast into areas they weren’t ready for, particularly the kobold-filled Nashkel mines.

The story was often sloppily told (starting with a villain who genuinely thought it a cunning plan to reverse his name from Sarevok to Koveras), and nobody cheered the addition of enemies like basilisks capable of one-hit killing the player character. (For reasons not hand waved until the second game, the party wouldn’t break out the resurrection spells for their fallen leader, making them seem like a bunch of real ungrateful bastards.)

But none of this mattered, at least at the time, primarily because of how much character the rest of the game had. It dripped with it, from the long conversations with your party to comedy moments with the NPCs—the highlight being the ability to have enough being dicked around and snap back with arguably the greatest dialogue option in the history of the genre. To whit:

“Okay, I’ve just about had my FILL of riddle asking, quest assigning, insult throwing, pun hurling, hostage taking, iron mongering, smart arsed fools, freaks and felons that continually test my will, mettle, strength, intelligence, and most of all, patience! If you’ve got a straight answer ANYWHERE in that bent little head of yours, I want to hear it pretty damn quick, or I’m going to take a large blunt object roughly the size of Elminster AND his hat and stuff it lengthwise into a crevice of your being so seldom seen that even the denizens of the Nine Hells themselves wouldn’t touch it with a twenty-foot rusty halberd! Have I MADE myself perfectly CLEAR?!”

Quite a jump up from Ultima’s “Name? Job? Bye.”

Needless to say, Baldur’s Gate 2 would see many improvements. The story is better, the pathing is better, and the second chapter, which sees you just trying to raise money by taking on jobs (each the equivalent of a D&D module in themselves) is one of the best in the genre. BioWare’s writing and design levelled up too, establishing romances as a key part of RPGs, and putting even more focus onto the party.

Something we’ve lost since then is the element of choice here, with the original Baldur’s Gate offering some 25 potential party members of every class and alignment, with scope for true inter-party clashes over good and evil, etc, versus just nine mostly forced-upon you in BioWare’s most recent fantasy, Dragon Age: Inquisition. Likewise, while that sticks to a party of just four, Baldur’s Gate offered six slots. You could even fill them with your own hand-crafted characters, albeit without any stories attached, or play multiplayer with friends.

The legacy of Baldur’s Gate does however continue, even with BioWare having moved on. Its engine, Infinity, gave us the great Planescape Torment and Icewind Dale, and remains so fondly remembered by RPG players that Obsidian was able to turn a promise to use something in its style into a hugely successful Kickstarter for what would become Pillars of Eternity. Elsewhere, and more controversially, Beamdog has continued working with the original games to produce the Enhanced Editions of both Baldur’s Gate adventures (including the expansion/finale Throne of Bhaal), and created its own completely uncontroversial interquel, Siege of Dragonspear.

And that’s not including the games that followed. Without Baldur’s Gate, we also wouldn’t have had games like The Witcher (the first one was built on the Neverwinter Nights engine), Knights of the Old Republic, Dragon Age or Mass Effect. Oh, or Jade Empire. Love or hate the BioWare legacy, the genre would be in a very different place if it had made Shattered Steel 2 instead.