Hands-on with the first hour of Tacoma

Science fiction is often at its least interesting when it’s at its most fantastical.

Interstellar lost me—spoilers—when it put Matthew McConaughey behind an interdimensional bookshelf. Star Trek thrives when it’s exploring what it means to be human, not when it's steeped in technobabble.

Mundane, everyday stuff makes for some of the richest territory in sci-fi. Sure, 2001 plops preternatural monoliths and Star Child in front of us, but Kubrick also lets us see the crew of the Discovery One grabbing lunch, or someone phoning their daughter to wish her happy birthday. Astronaut Mark Watney solves life-or-death problems in The Martian, but along the way he’ll muse about the Three’s Company episode he’s watching.

What I took away from playing Tacoma, the new first-person exploration game from Fullbright, is that it will be a sci-fi story you can relate to. Yes, it’s set on a space station, in a universe where people’s conversations can be played back as AR holograms, and sure, there’s an omniscient AI plugged into your ears that may or may not have killed your colleagues. But along the way, the stuff you’re stumbling on, reading, and listening to in this seemingly-abandoned space station is endearingly everyday: love notes, lunch appointments, doctor’s visits, or your crewmate’s embarrassing search engine history.

“At the end of the day, we want to be able to tell stories that are just about people,” says Steve Gaynor, designer and writer on Tacoma. Gaynor says that he wants players to walk away with the feeling that they “got to know this group of people and understand what they went through, and feel for them, and have some empathy for their situation.”

One of those relatable discoveries comes when I wander into a room where one of Tacoma’s six crewmembers has left a guitar. It’s a banged-up acoustic, the kind you might find in a pawn shop, floating in zero-G alongside emptied drink bags. On the wall are rows of tacked-up post-it notes, with crudely-drawn tablature penned. It’s the simplest way for someone to write a melody on a wall, the sort of thing you’d expect to find in a high schooler’s bedroom, not miles above the Earth.

Space eavesdropping

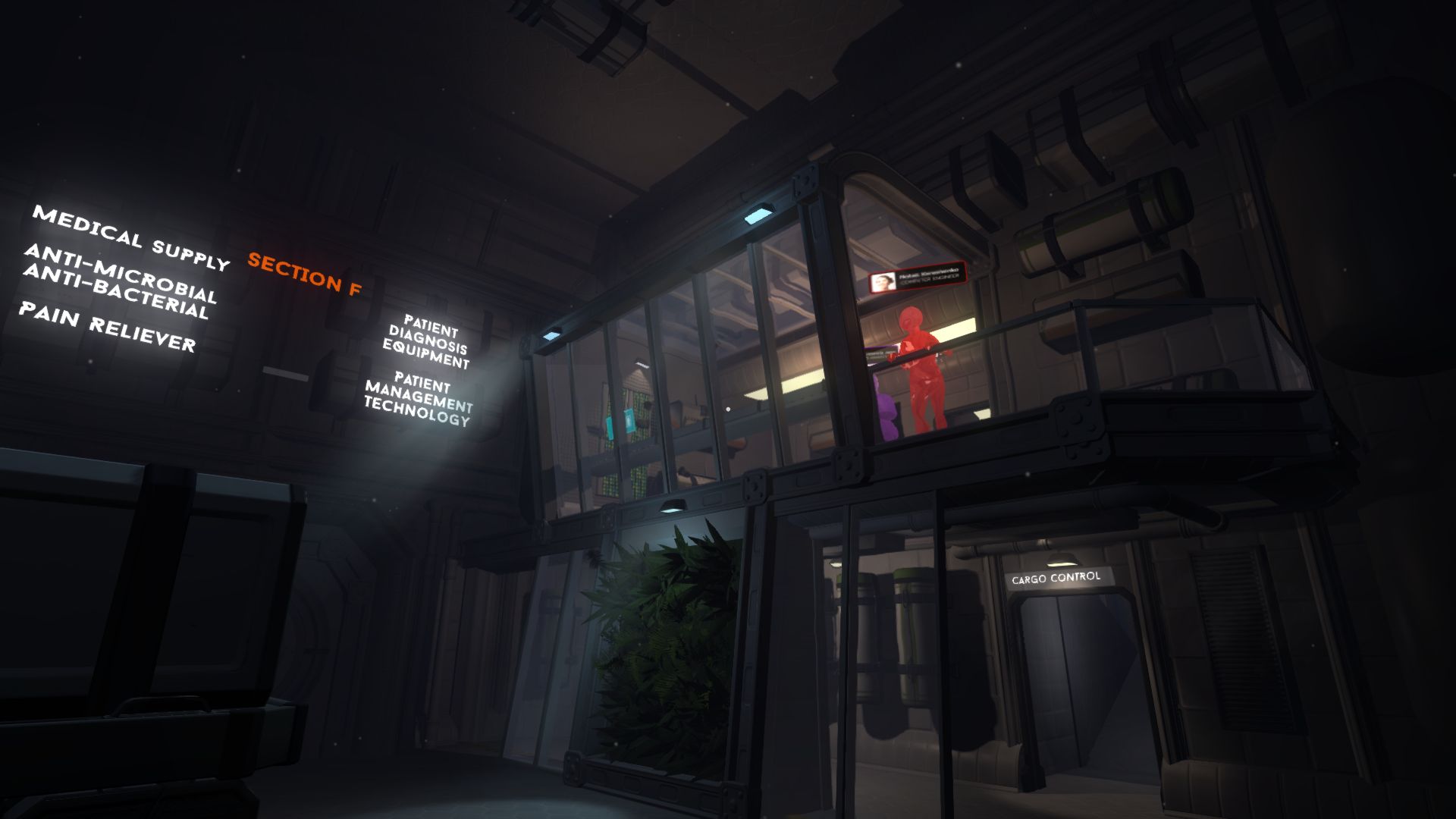

I only played Tacoma’s intro—about an hour—but it was enough to give me a sense of the types of interpersonal stories it’s going to touch on. Through Tacoma’s entry corridor, up the orbital lounge and toward the cargo area, I find an empty medical bay, a two-room office. There’s an AR indicator floating in the air, a flat piece of UI hovering in 3D space. I tap it, and single-colored, life-sized mannequins spring to life, stand-ins for the crewmembers who had been there before. As the AR recording plays back, I learn that ODIN, Tacoma's AI system, has detected an issue with one of the crew. Clive, the operations specialist that your character is sent to replace, has to return to Earth as soon as possible. I hear him share this discovery with E.V., the Tacoma administrator that he’s romantically involved with. They’re both worried about how they’ll carry on, expressing the kind of separation anxiety most people have experienced when they have to consider whether they’ll pursue a long-distance relationship.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The Tacoma crew all committed to one-year contracts when they joined. And to help Fullbright better understand what the characters of Tacoma might realistically go through in their situation, Gaynor says they’ve spent time researching the routines of people who’ve lived on the ISS or in other isolated areas, like Antarctic research outposts.

“They had to figure out how to get by. Some people get really anxious or depressed. Or they get cabin fever. Or people get into really intense relationships.” As your character explores the mystery of the absent crew, Gaynor says that Fullbright wants to capture how the six crewmembers coped with their distance from the Earth. “They all come onto this station as individuals with jobs, but they only have each other to rely on during this whole time. So in some way it’s about how this group comes to rely on each other and becomes a family,” he says. “We encounter a lot of sci-fi that is more about plot and more about the, you know… the plot that the progenitor race has to destroy humanity or whatever. And the stuff that I connect with the most when I’m playing any game like that is when you’re totally outside of that ‘fate of the universe’ scale of conflict and you can just see, ‘Oh, this is just a person that I could know in my everyday life.”

The demo left me with a lot of questions about what lies ahead (it ends with your character, with concern in her voice, asking ODIN “What am I going to find behind this door?”). Tacoma is an evolution of Fullbright's work on Gone Home—patient storytelling through artifacts and notes, but in a much bigger and more imaginative space. Sci-fi as a setting does grant Fullbright some new storytelling tools, like the AR embodiments of your crewmates (which allow for actual dialogue, not monologues and diaries), and the virtualized bits of text that literally float in the air, rather than hide in drawers and on bookshelves.

One thing I’m hoping I'll be more impressed by when Tacoma releases in 2016 is the look of Tacoma itself. The space station didn’t feel any less populated with ephemera—if anything, there was more stuff to read and sift through than Gone Home, a reflection of the larger, albeit still absent cast of characters. But Tacoma, right now, feels less dense than Fullbright's first game. Maybe that's a natural result of the setting being a functional, highly engineered, more spacious thing—it's more sterile than a family home. But compared to say, Adrift, which is admittedly more linear, I didn’t feel caught up in the elegance of the station itself, in the contour of its bulkheads or the way lighting cuts through exterior windows.

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Arma 2. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging. Evan also leads production of the PC Gaming Show, the annual E3 showcase event dedicated to PC gaming.