Space Beast Terror Fright is Aliens meets slapstick

We write about FPSes each week in Triggernometry, a mixture of tips, esports, and a celebration of virtual marksmanship.

“There’s nothing wrong with you, it’s just really hard,” Johannes Norneby tells me. He and Madeleine Bengtsson are consoling me from their home in Götenborg, Sweden. I confessed that my first experience with their game, Space Beast Terror Fright, ended in a flash, a scream, and a bloody death. It turns out that’s how it goes for everyone the first time.

In SBTF, armored marines board ships overrun with pissed-off aliens. The plan: get in, pull the data servers, set the engine to overload, and get out. The game takes inspiration from familiar aliens-vs-marines setups: Games Workshop's Space Hulk and James Cameron's Aliens. The heart of SBTF, though, is its use of campy, over-the-top humor as a balance for jumpscares and horror.

“You watch some people who are really well organized and they have a plan. They’re in the airlock and they’re all ready to go and they’re being so serious,” Norneby says. “And then they open the airlock and they take two steps and everyone dies… Then they start to laugh.”

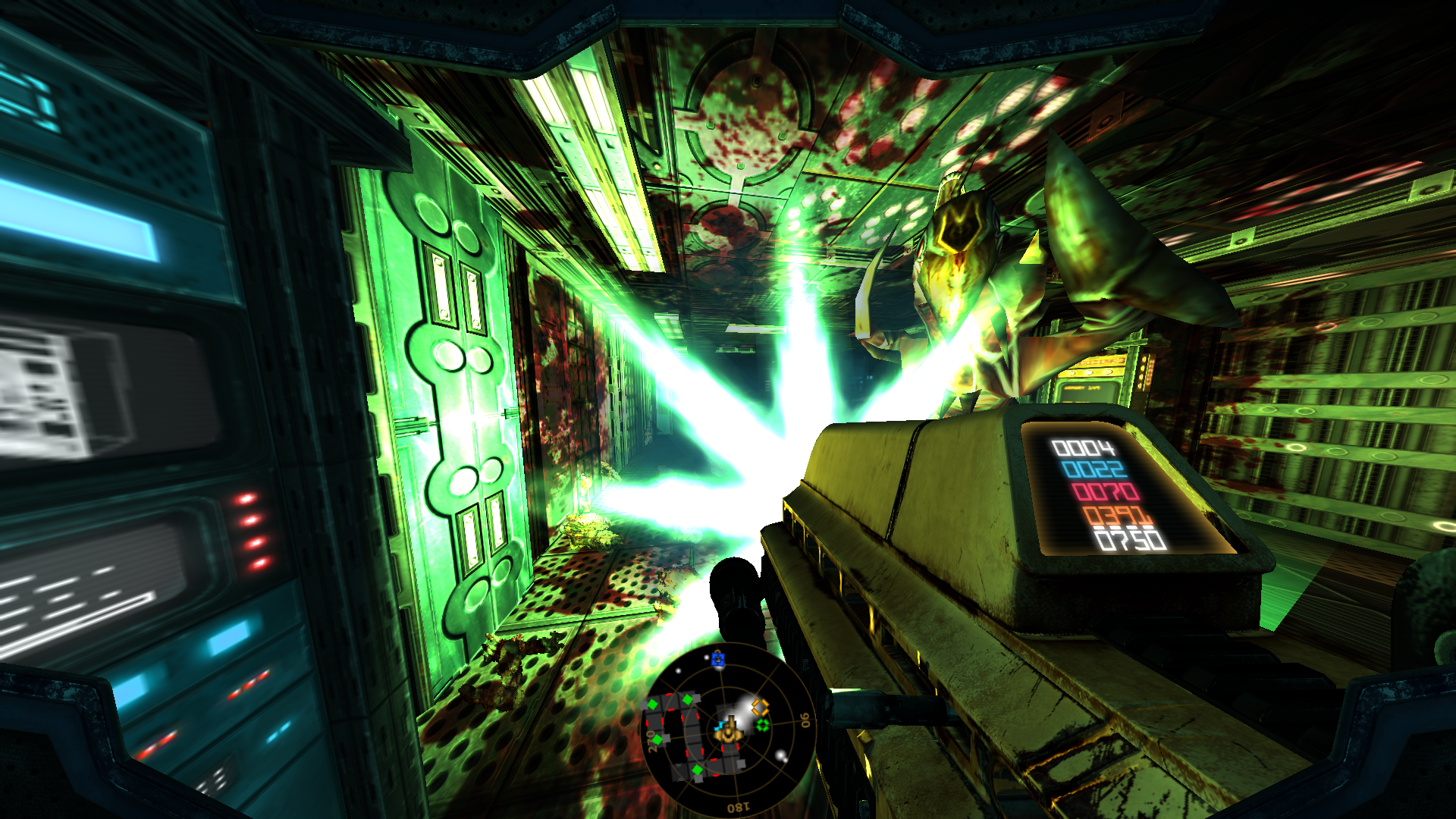

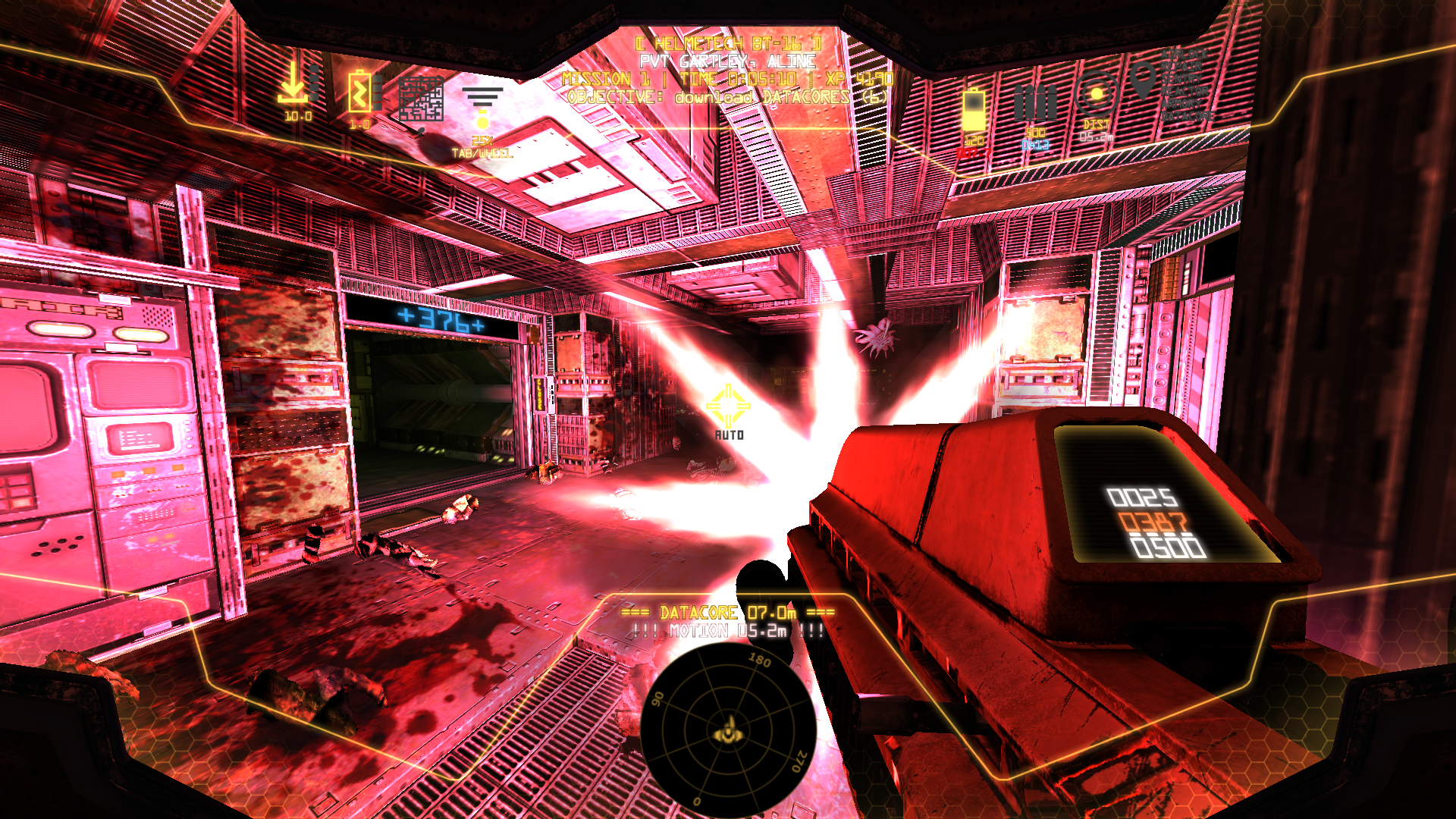

Marines in SBTF are clunking, armored monsters themselves. A cluttered heads-up display augments the dim interior, lit only by flashlights and emergency bulbs. The walls bristle with CRT monitors and dead switches. The first-person perspective is claustrophobic and chaotic—the marines themselves so massive they block entire hallways.

Like Aliens itself, SBTF missions are cinematic. Things start slow, with scattered groups of aliens hiding down lonely, clean hallways. More and more aliens pile in as the team pulls out the ship’s server hardware. The mission builds to a crescendo as the marines shut down the engine coolant and haul ass back to the airlock through waves of angry teeth.

Into this bleak environment, the humor leaks through in small ways. Alien and human corpses explode into showers of blood, decorating hallways with chunks and arterial spray. A good-sized battle leaves a squishy carpet of parts for the survivors to wade through.

Then there’s the guns’ comically bright muzzle flash. It is blinding, like firing the Death Star’s main gun inside a shoe box. I ask about the muzzle flash, which takes up so much screen space that I focus on short bursts not just for accuracy, but so I can see what’s going on.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“Well, you want the weapon to be powerful,” Bengtsson says. The guns are definitely powerful. Along with the huge muzzle flash, these high-caliber beasts kill aliens in one or two shots. Laughing with glee is common. “You need to have a powerful weapon to combat how difficult the game is,” Norneby agrees, “and then I realized that you can make the player more powerful if the game is harder, and that sort of escalated.”

Giant guns and giant marines and giant alien insectoids: it’s all a silly veneer on a game that rarely gives a moment to breathe, and that’s on purpose. “If the game was this hard and serious, people would think that it was just too hard. That’s the reaction we got from our friends in Sweden: no one would laugh at it, they just thought it was too hard.” Bengtsson laughs. “It’s too much for Sweden. Swedish people are, like, more mellow.”

Norneby has a background with the Swedish games development industry, working with studios like DICE and Ubisoft in that mellow environment—which he calls “super serious.” He wanted to be a little ridiculous, but he saw little room for whimsy. “If you think about The Division and what that’s become. If you think about DICE and Battlefield—you couldn’t put Super Mario in there, you know?”

Instead, Norneby and Bengtsson took a prototype to Steam Greenlight, and the positive response there prompted them to work on SBTF full time. “We really struck a chord internationally with this, and that was really cool and vindicating,” Johannes says. “It seems like, especially North Americans, they’re like, ‘yes, this is crazy! It ate my face in two seconds, I want to do it again!’” With no one to tell them no, they’re specializing in silly. “The things we’re doing—we’re putting our own scared faces on the marines... It’s all the stuff from a [ridiculous] standpoint that I was never able to do.”

The humor might take a bit of the sting out of losing, but eventually players will want to win. What Norneby and Bengtsson are seeing is that successful players in the community share a love of much more serious games like Arma. “To me that’s sort of illogical, but in a way, there are aspects of our game that are—it’s not that they’re realistic, but they’re systemic… Nothing is scripted, we just build a system and throw people into it and see what happens.”