Sort characters from cut-outs with the Plinkett Test

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Mr. Plinkett is the alter ego of filmmaker and critic Mike Stoklasa. His feature length reviews of the Star Wars prequels are hilarious, incisive video essays that reveal in excruciating detail just how badly George Lucas screwed them up. They’re amazing, and I’ve watched them more times than I can count. Even though he’s playing the role of a cranky old serial killer, it’s clear that Stoklasa knows a lot about film. The criticism and insight in his reviews is brutal, precise, and razor-sharp.

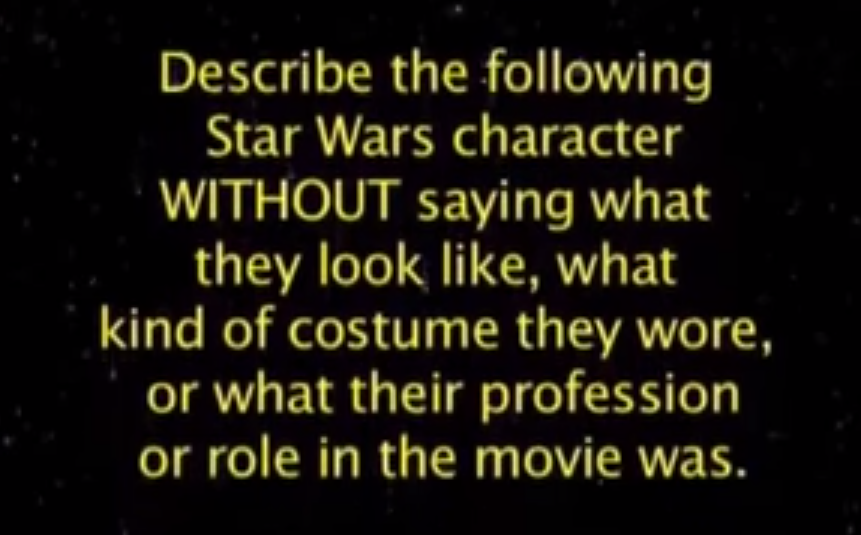

I think about Plinkett’s videos a lot when I’m reviewing games. There’s one moment in particular, from his Phantom Menace review, that has always stuck in my head—and has ruined a lot of games for me. I call it the Plinkett Test. To prove just how forgettable the characters in the prequels are, he asks a group of friends to complete the following mental exercise. Skip to 6:45 in the video to see it for yourself.

They have no problem describing classic Star Wars characters like Han Solo and C-3PO, but struggle when it comes to the likes of Qui-Gon Jinn and Padmé Amidala. The best word Rich Evans can come up with to describe Qui-Gon is ‘stoic’, while another interviewee sums Amidala up as ‘kinda normal, I guess.’ The point is, the characters in the prequels are, almost without exception, utterly one-dimensional. They aren’t people: they’re costumes. And this is a clever way of pointing that out.

Article continues belowIt’s a test that can be applied to video game characters too. It’s far from scientific, but it’s a good way to determine if a character is, in fact, a character, and not just someone defined by their appearance or actions. When I play a game I mentally run the cast through the Plinkett Test—and very few pass. I’ve even asked writers in press interviews to run their own characters through it, and it always leaves them flustered. Try it yourself. Think of a few game characters, then describe them without saying what they do, what they wear, or what they look like. It’s difficult, right?

Earlier I accosted a few people in the office, read out a list of characters, and asked them to put each one through the Plinkett Test. They had no problem describing Grand Theft Auto V’s retired bank robber Michael De Santa. “Cynical.” one said. “Stuck in the past.” another added. “Self-hating.” Then I asked them to describe long-time Resident Evil villain Albert Wesker, and there was a lot of pausing. I could tell they were dying to say ‘sunglasses’ or ‘blonde hair’, because that’s all Wesker is, really. “Evil?” said one person, unsure. “Uh, he’s really bad. Not nice” said another.

Resident Evil is the perfect example of characters who aren’t really characters. I love the series, and I have a fondness for people like Barry, Chris, Claire, and Leon. But I think that’s nostalgia at work more than anything else, because they’re defined by their outfits, not who they are. Barry Burton is a beard. Leon Kennedy is a fringe. Wesker’s a pantomime villain in shades. Sure, they’re really good at killing zombies, and Leon can suplex parasite-infected cultists like a champ. But it’s the time I spent with them that makes me like them, not the characters themselves.

To be clear, the Plinkett Test isn’t a method for determining if a character is a good character—just that they are one. What I noticed from my experiment was that many of the examples on my list were described with words like ‘brave’ or ‘driven’. These, to me, aren’t really personality traits: they’re the result of a character’s actions or circumstances. Of the lot, it was BioShock’s Booker DeWitt the people I asked struggled with the most. No one could pinpoint his personality. I couldn’t either—and remember, this is a group of people who have played and finished the game.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There’s an argument to be made, perhaps, that Booker DeWitt—and other protagonists—aren’t really supposed to be characters in the traditional sense. They’re a blank canvas for you to imprint yourself on. An avatar. But if that’s the case, why does Booker speak? And why is he voiced by Troy Baker? Some characters don’t need personalities—Half-Life’s Gordon Freeman being a prime example—because they are, ostensibly, you. But that isn’t always the case, and the avatar defence isn’t a get out of jail free card. Some characters are just badly, or barely, written.

Lots of wonderful, memorable stories have been told in video games, but this is rarely because the character has gone on some emotional journey—rather that they’ve done something cool or memorable. Games are often better at telling stories through their environments, not their scripts. SOMA is a recent example of this. I sometimes wonder if this is a limitation of the medium, because developing a character across 10-12 hours in an interactive game is very different from doing so in a film.

But then I think about the games that do have fleshed out characters: Mass Effect, Metal Gear Solid, Dragon Age, Her Story, Final Fantasy, Silent Hill, Planescape: Torment, The Witcher, Grim Fandango, The Walking Dead—the list goes on. I’m not saying the characters in these games are up there with great literary works or classic cinema: just that they have identifiable traits that give them some substance. So, next time you’re playing a game, run the characters through the Plinkett Test. You’ll be surprised by how many of them fail. And email me if you want a pizza roll.

You can watch all of Mr. Plinkett's movie reviews here.

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.