Short Trip: an interactive illustration that took five years to make

How artist Alexander Perrin created a peaceful pencil-art meditation about a cat and a tram.

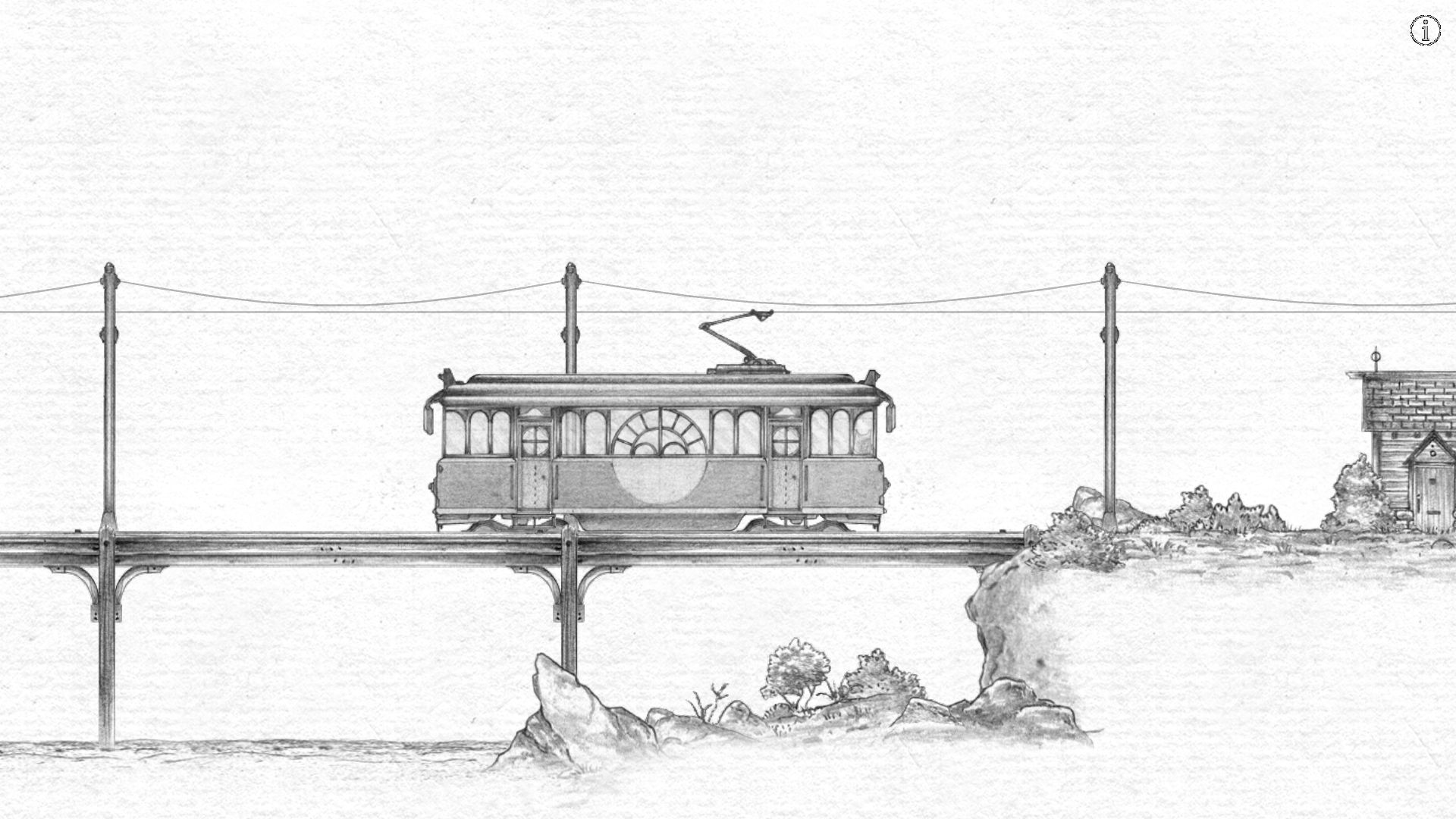

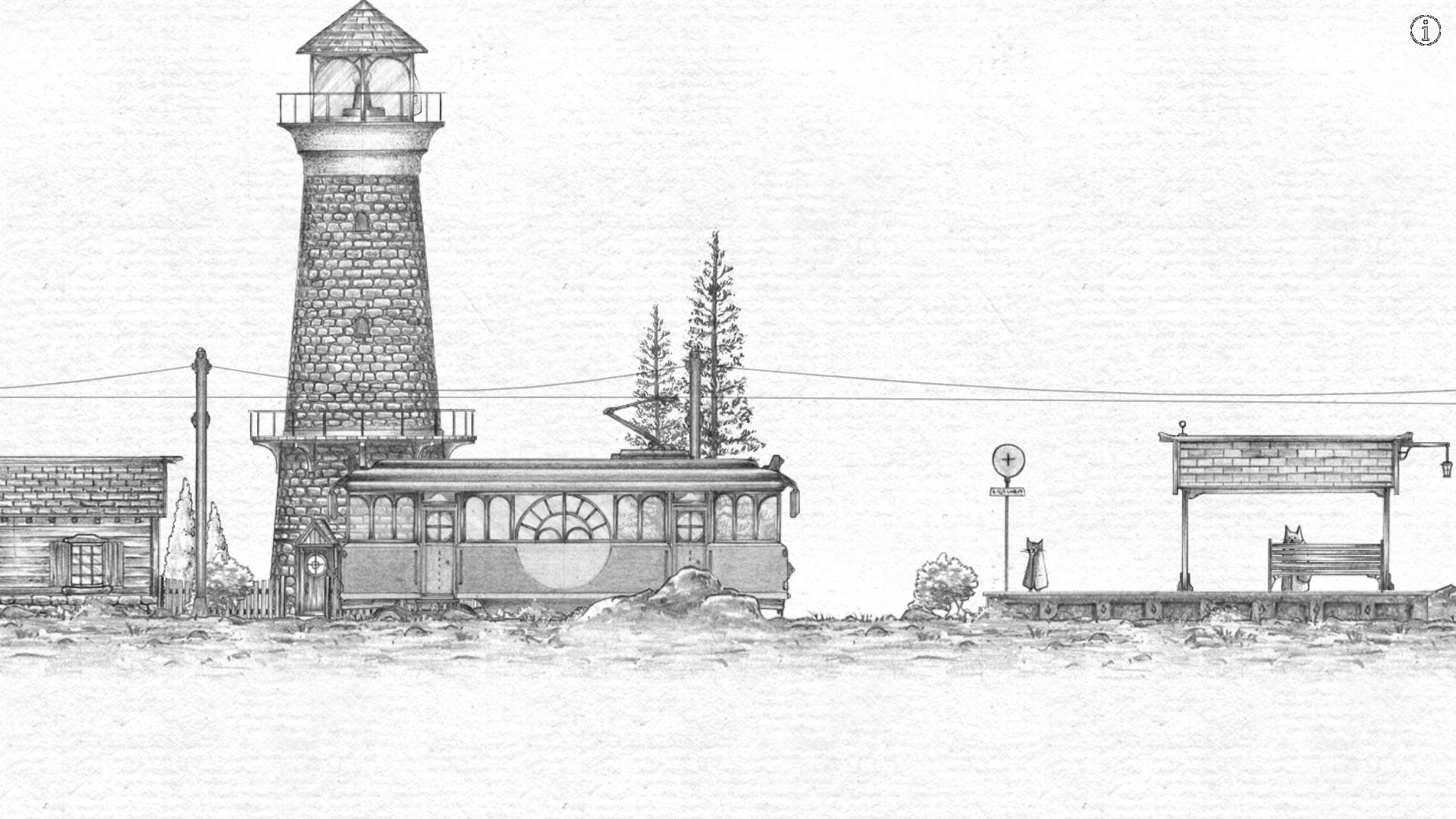

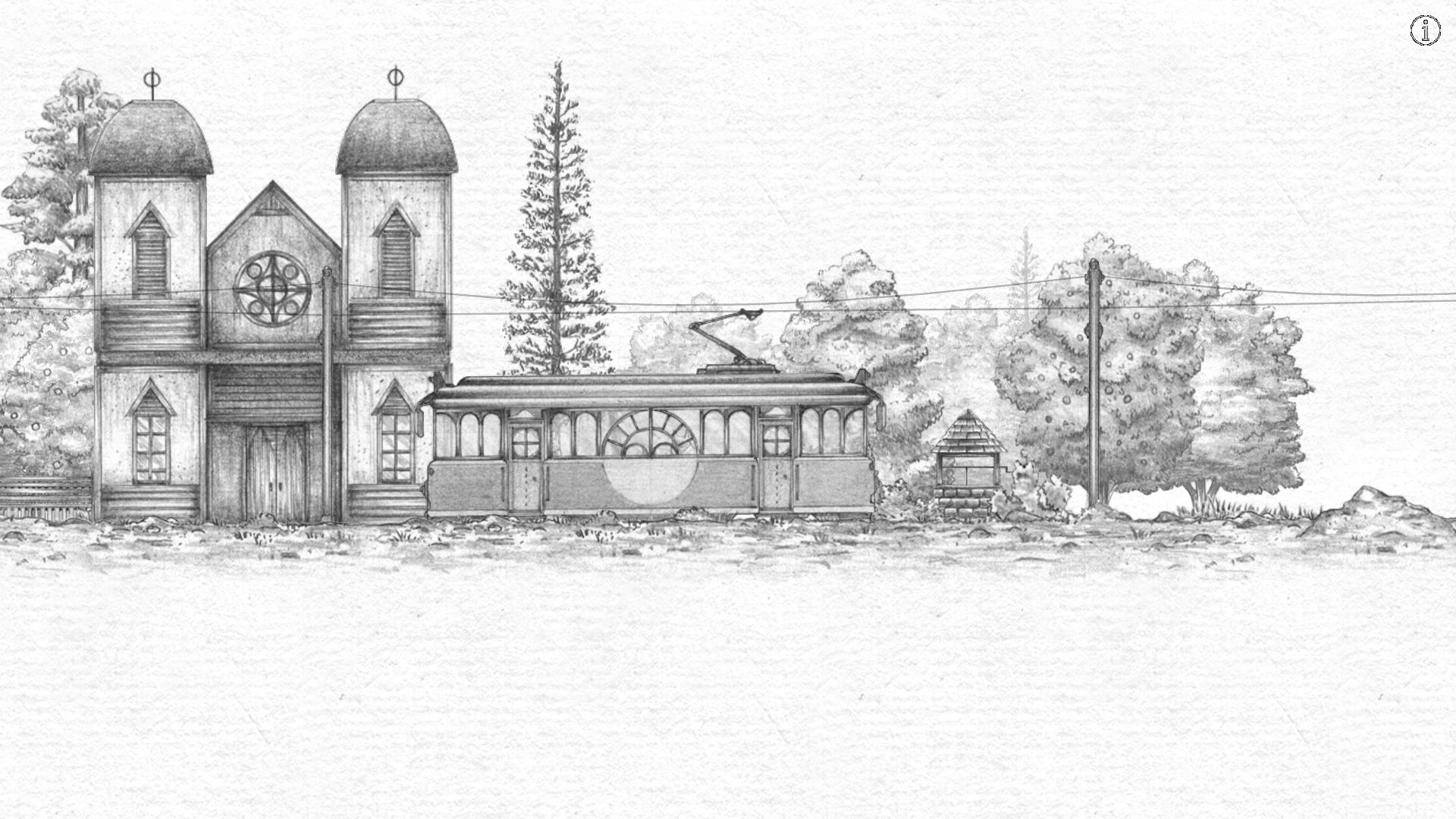

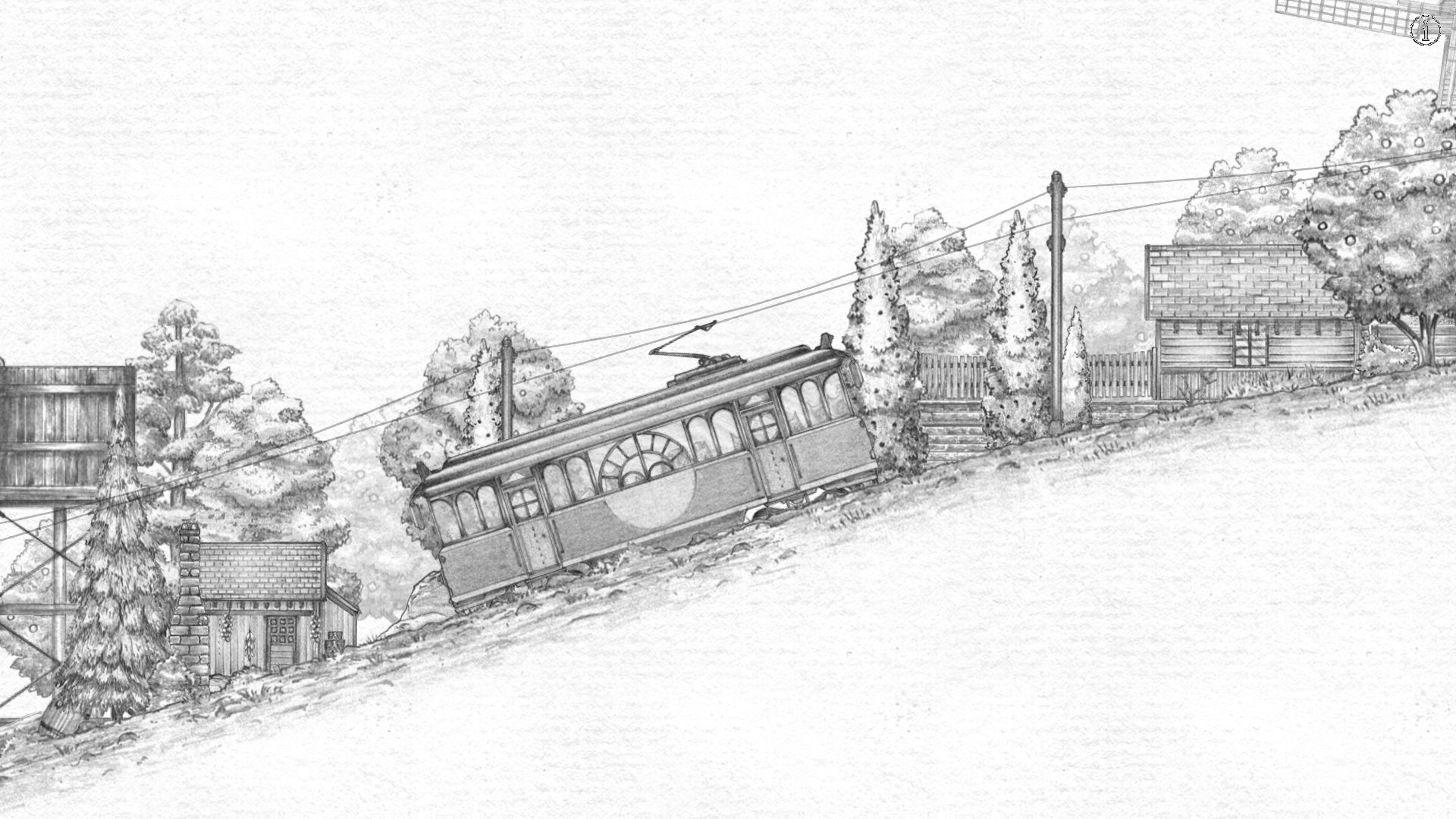

Faded, silvery graphite sketchings of trees. Babbling brooks and rolling hills. The twittering of birds and the sighing of the wind. These things pull you into a dreamlike world, a mystical land blanketed in peace. In this new world you’re cast as an anthropomorphic cat, hopping about on two legs. Using the right and left arrow keys to move about, you happen upon a tram, and you’re off on your way through an idyllic storybook countryside.

Short Trip is an experiment in digital illustration by Australian artist Alexander Perrin. It’s the first part of a series in which Perrin aims to temporarily send his audience to another world. A fleeting experience, lasting just five minutes or so, it captures the feeling of a quaint journey perfectly.

Perrin says he got the inspiration for Short Trip from the Hakone Tozan railway line in Japan, a small electric train line that travels through the rural mountainside of eastern Japan, south of Tokyo. Perrin says the Hakone Railway reminded him of a model railway, "just massive but in a way that every piece of rail is easily integrated into the landscape and into the trees and everything just sort of fits magically," he explains. "It all feels illustrated."

Dreamy Japanese railways weren’t the only source of inspiration for Short Trip. He drew from a collection of influences that struck him over the course of Short Trip’s five-year creation including Eastern European architecture and his mother’s eclectic home decor. As he collected inspiration over the course of those five years, he drew single images of trees or plants here and there until a world started to emerge. Part of the reason it took so long is because Perrin works a day job to support his art career.

I thought it was just interesting to see if it actually could be done with two pencils alone.

Alexander Perrin

"It was the only way I could get this done. Just being able to make these little drawings, like little visual components one by one, and incrementally add them into the world over the months and then years, was actually just a practical way of doing it," he admits.

While it was a slow process, it’s also something Perrin revels in both from a creative perspective and as a videogame enthusiast from childhood. Growing up, Perrin was drawn towards games that allowed players to create their own worlds and civilizations. "There's something extremely quixotic and therapeutic about building and constructing and forming worlds full of life even though they're all digital," Perrin says.

Perrin created his own 'asset library' for his art inspired by his favorite games, like Age of Empires, which allowed players to create structures and worlds from a library of objects—walls, trees, rocks, and more. "I think one of my greatest joys about creating games and virtual worlds and spaces or any sort of art is being able to create smaller components and stack them, and make a library of my own assets, which I can use to create my worlds."

The illustration was a technical challenge of sorts for Perrin, who was trying to make something that hadn’t been done before. He wanted to create a browser-based world purely illustrated in graphite. "I thought it was just interesting to see if it actually could be done with two pencils alone. And I think it worked," Perrin says.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It did. The soft graphite lines of the illustration lend themselves to Short Trip’s whimsical storybook quality. Digitizing the graphite illustrations themselves was a relatively easy process for Perrin, who simply scanned them in and did a few touch ups here and there.

"The natural roughness and the grain of the graphite and the paper meant that a lot of the scenes are hidden," Perrin says. Normally, when creating art using digital media, it’s harder to hide flaws in your artwork because all of the lines are so precise. That’s not the case with graphite. "I feel like the natural nature of the physical mediums hide all the yucky stuff, so it was really quite encouraging in that way," he explains.

It was definitely built also as a tool for people to just chill out for five, 10 minutes, however long they want to

Alexander Perrin

However, animation did present a few challenges. "In the game, a lot of the moving objects, like the windmill, while it felt interesting, you really had to make everything really subtle because the graphite is not really meant to be moving," Perrin notes. "When [it] did start moving, it sort of lost the magic of its natural qualities, and just looked like a kind of cheap digital reproduction. So, most technical challenges were finding out how high to push the graphite into the digital context and find where its natural limits were."

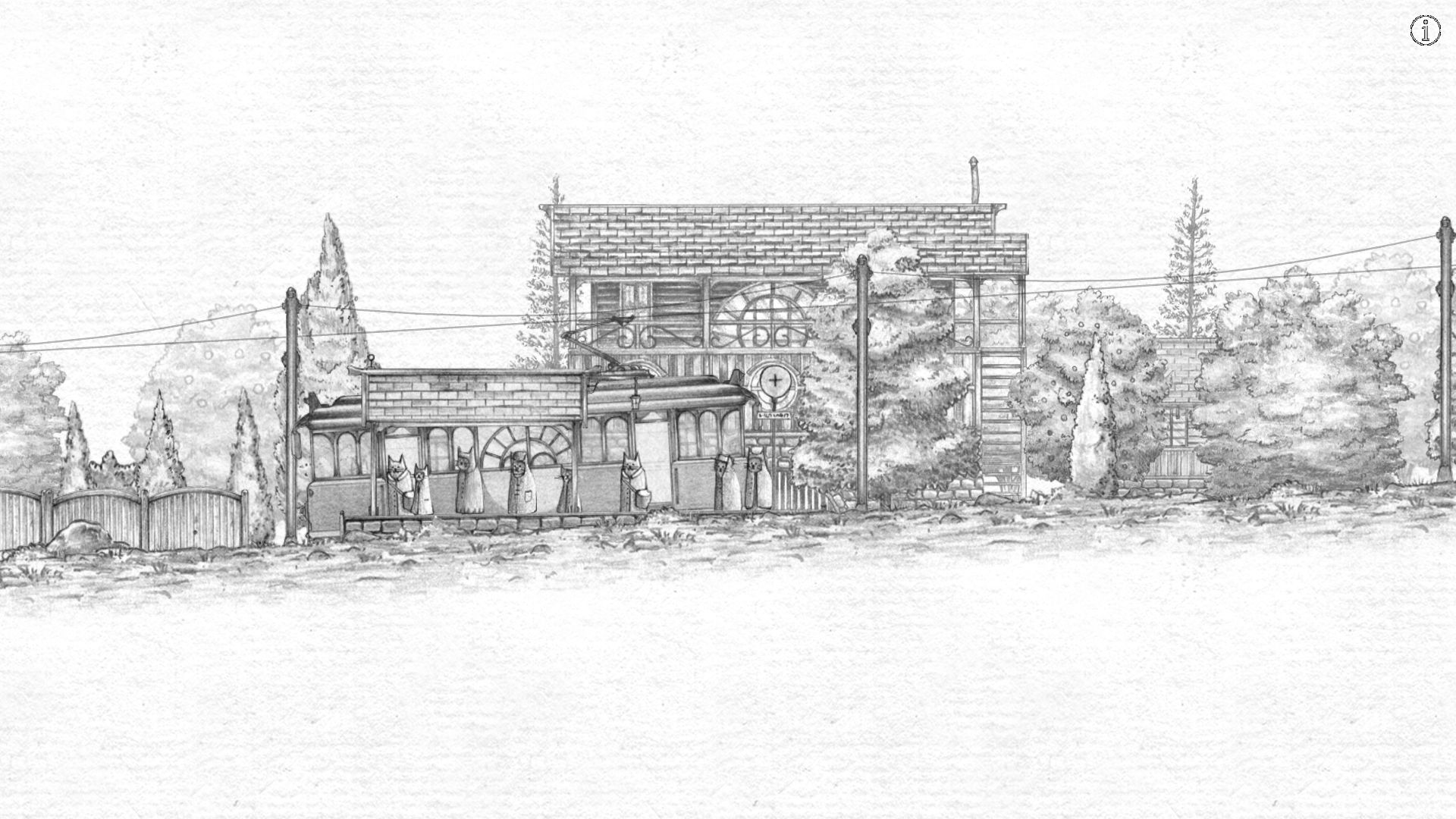

Stylistically, Short Trip masks these difficulties quite capably. "Even the characters, their legs, nothing on them really move. They kind of hop about, but it really works because they're kind of like paper cut outs, and it didn't shatter the graphite style," Perrin says.

The final product, once the illustrations and animations all came together, is not exactly a game, but an illustration with participatory elements. This was a deliberate choice on Perrin’s part.

...it was up on a screen, and they built a big controller for it using some sort of hacked electronics kit so kids could go up and push these buttons and ring the bell

Alexander Perrin

"I wanted it to be a really appealing and not alienating project for a much wider audience. Particularly those who find the term videogame [has] a bit of a stigma, or so that older audiences can pick it up," Perrin says.

Perrin’s term of choice instead is 'interactive illustration.' "It’s something [where] the main focus is to chill out and observe. It's a very passive experience in a way," he adds.

The internet today can be a stressful place, with the overwhelming shadow of social media and a constant news stream. Experiences like Short Trip, designed to be played right there in a browser, provide sweet moments of respite.

"It was definitely built also as a tool for people to just chill out for five, 10 minutes, however long they want to," Perrin notes. "There's a lot of anxiety-inducing content out there, so I think that's just meant to calm that, there's plenty of room for that."

Accessibility was also a big goal for Short Trip. Perrin wanted a wide audience to discover it. "I'm very happy that it was able to run on most web browsers. It opens up the audience for people who can play it, people who aren't familiar with itch.io and don't want to download stuff to their computer can just see it there and then," he says.

That accessibility has produced interesting results. Perrin recalls seeing a picture posted on Twitter of a grade school class playing the game on a projector. "I think it was a library or something, and it was up on a screen, and they built a big controller for it using some sort of hacked electronics kit so kids could go up and push these buttons and ring the bell and see [the tram] move.”

Perrin says he doesn’t mind if people call Short Trip a videogame or something else, but the internet could use more digital experiences like it—the kind designed to provide a sense of peace in a chaotic, competitive culture.