Sam Barlow on #WarGames, Her Story, and reflecting real-world politics

"It's not fair to say that all technology is evil. That was something I took from the original WarGames movie."

Sam Barlow is a videogame designer whose career spans three decades. During that time, he's worked on everything from Serious Sam: Next Encounter to Silent Hill: Shattered Memories—but is perhaps best known for his work on Her Story, PC Gamer's Most Original Game of 2015.

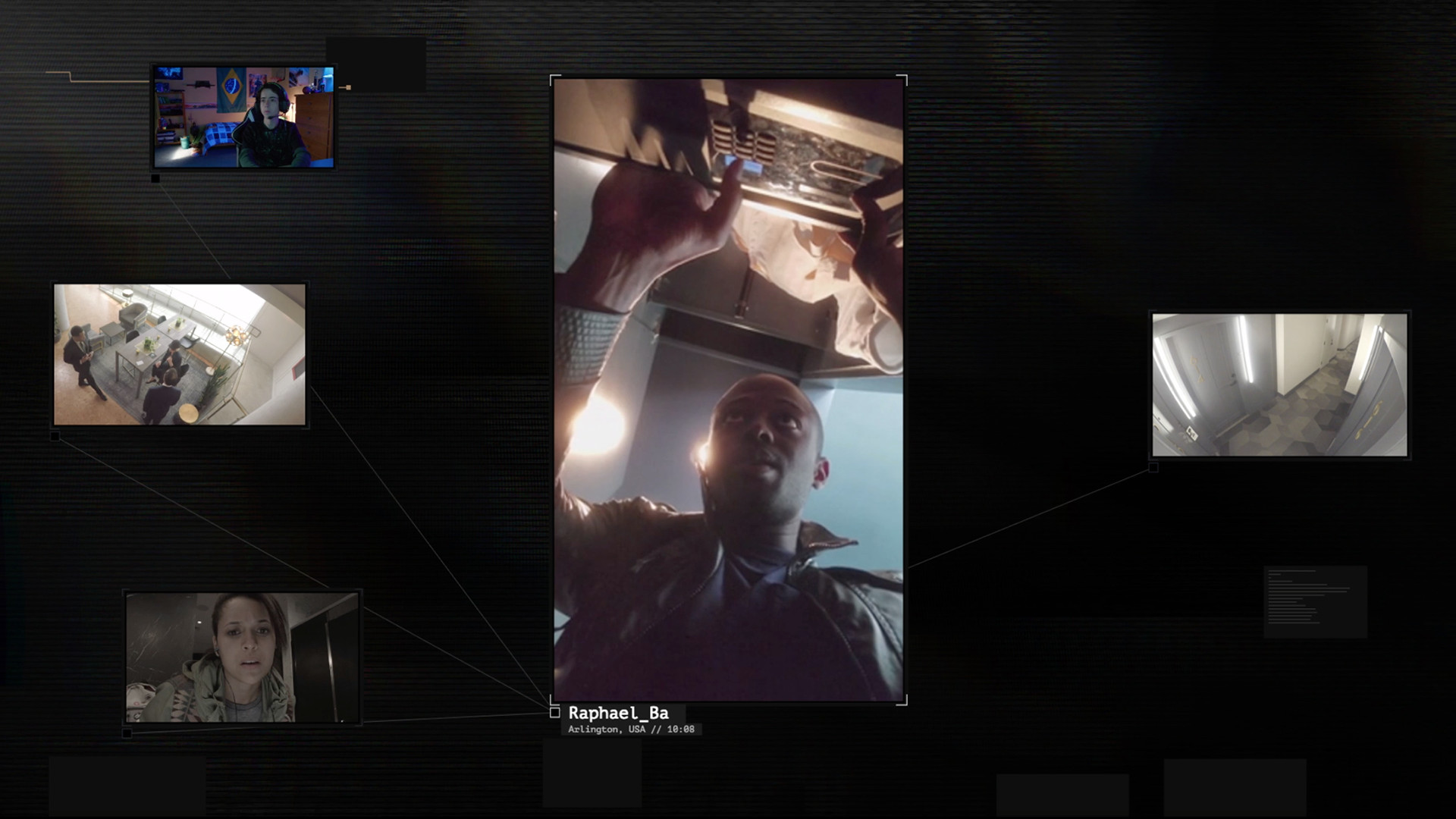

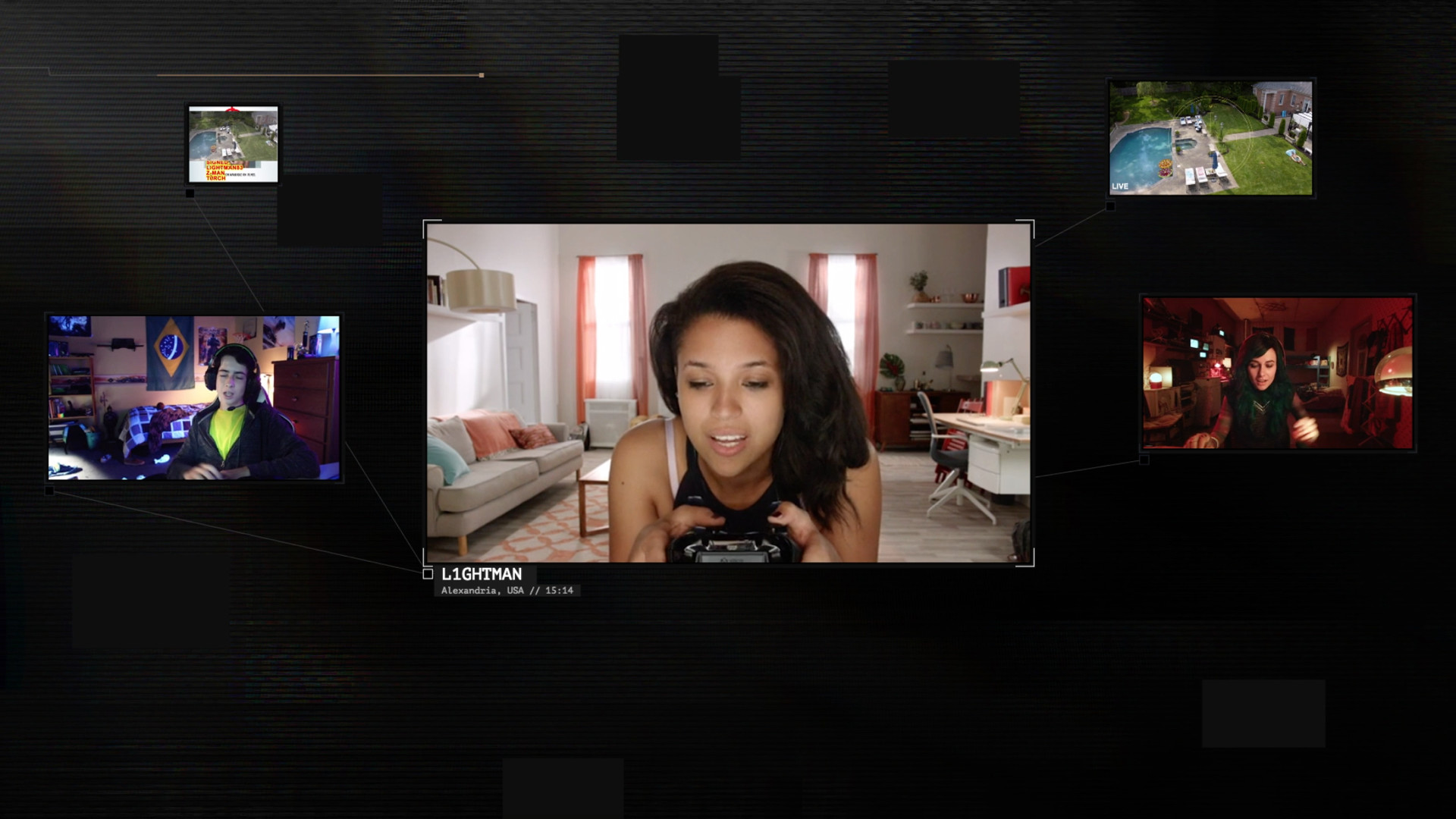

In the wake of his most recent venture—Eko's #WarGames, a reimagining of the 1983 movie of the same name—I caught up with Barlow. We discussed his passion for branching narratives, moving on from Her Story, his admiration of streaming service algorithms, and how much he feels his games should reflect real world politics.

PC Gamer: Like Her Story, #WarGames is an unusual idea.

Sam Barlow: Yes, it is. #WarGames is an interactive show with six episodes. It's a full series in the UK sense—in America it would have to be defined as a mini-series event. It's doing five or six things when someone more sensible would try to pull out two or three. It is taking the heart of the original movie.

When I think about that movie, I think of the effect it had on the young audience watching it, the fact that it introduced the idea of hacking to the mainstream, and the things that stood out for me when I went back and rewatched it, when I thought about whether or not I wanted to do a reboot, was the fact that Matthew Broderick's hacker protagonist is actually still pretty unique in that he's not the dark, tortured hacker protagonist that tends to be what we think of—he's actually this charismatic, fun, jokey kid. In class he's the joker, he's this very likable guy, the essential Matthew Broderick persona. That whole movie being about this whole generational clash where you have Broderick and Ally Sheedy as they two young kids and they're somewhat naive and they go up against their parents' generation and the Cold War.

Those were things that really resonated with me because I would feel disinclined to do anything about WarGames that's a direct follow-up. I think it's such a film that was of its time and place. It's about the technology of the time, it's about the political climate of the time. So, while thinking about doing something with it, I was thinking about how easily you could update this thing. It's like: Hang on, we have a whole new generation of young hackers who are going out there and hacking into military systems and doing this stuff. This is happening everyday, it's not just stuff of Hollywood movies.

In so much as our political situation is concerned, it's completely changed. We're now living in this, in the last few years, new world where there's a massive upswell in resistance and activism amongst the young. There is to some extent a clash of optimism and youthfulness versus the entrenched, ridiculously complicated mechanism. It felt like playing with the idea of the movie was something we could play with—and coming off of Her Story, one of the things that was exciting there was the range of audiences that loved that game. I loved talking to people who told me they didn't really play games, that they were lapsed gamers, they'd never played one in real life, or that they didn't realise Her Story was a videogame until someone else told them. It was exciting that that audience was there and it was an audience I'd never been able to address.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

How did Eko approach you?

I was brought in and was, of sorts, the token videogames person—albeit with a slightly nuanced view of the videogames industry. I was saying: Look, there are all these people who have done cool things in the interactive space, and they're not necessarily the person who's writing the dialogue for the next Call of Duty. There are people over here doing these cool things with Twine, there are people over here who did this cool thing ten years ago, you know, there are all these people that have been trying to solve this problem and there is stuff to be learned from that. During this discussion, I was asked if I'd be interested in doing something with WarGames, and from there I was interested in seeing what other audiences were out there—could I tackle a bigger audience?

And could you?

We've had these discussions in the past. When mobile blew up, there was all these discussions around free-to-play and how that was killing the kind of games I loved making. I saw that happen where I was invested in making the AAA story games—I got the chance to work on Silent Hill, then started working on Legacy of Kain for Square Enix. If you'd asked me to predict the future, I'd have said, clearly publishers are getting behind these narrative-driven games. Things like BioShock are going to become the norm where publishers feel like there's something slightly worthy and there's a level ambition behind the narrative—and there's also this big budget. That was necessary in the videogames space, and where you wanted to have a close up of character's face and capture emotion, you were talking about blockbuster money for performance capture.

When mobile came along and the numbers became exponential there, and games as a service became a big deal, there were loss of discussions within videogame circles that questioned how you free-to-play narrative. Within the logic of videogames this was something they could never get their heads around. Narrative is, essentially, finite content, it's expensive content. You can't spread it around like you can gems. The direction Eko are coming from, though, is looking at network TV. Particularly in the States, this is a foundation for telling stories on the screen, and it's also very tied up in the world of advertising. That's boring business stuff—but things like Steam and the App Store are in fact the big game changers that change things.

With #WarGames, we were looking to play on some of the things that are cool about Her Story in terms of telling a story with live action video with a level of interactivity, albeit a different feel of interactivity. A lot of the feedback I got from people was that they felt like they had a more intimate connection and that this felt like a more personal experience and as much as Her Story goes out of its way to abstract things, it's literally a game about playing with a database.

To that end, videogame full-motion video projects often employ gimmicks or novelty angles. How aware of that are you required to be going into projects like Her Story and #WarGames?

Games have tried to do interactive dialogue for a very long time, and it's still something we haven't perfected yet. There are times when you want to say something and you can't. Or the reaction you get from someone feels a bit off. Or the pacing of it doesn't quite work. What I did with Her Story was essentially just ignore all of those problems by saying, I'm not trying to simulate all the dialogue—you're interacting with a database. But the best feedback I got was people saying, because I didn't worry about all those things, actually, the loop I was in, the feel that I got, from Her Story was that I was in some kind of conversation.

Games have tried to do interactive dialogue for a very long time, and it's still something we haven't perfected yet.

There's a very solid idea of what choice looks like in a game. You might see that in a BioWare game, a Telltale thing, maybe like Life Is Strange and it's like: Okay, I'm controlling the character and I may or may not get to push them around. But at some point there will be dialogue or action and I'll get a choice, and it will probably be a choice between three or four things. There will be some text on screen, and I will have to from that text infer what I'm choosing.

This is where I start getting stuck—you're starting to play that game where you're guessing the author's intentions. The worst thing in those games is when you pick that choice and the character does something you weren't expecting, or where you really want to do something specific and there is no option to do that. It's a craft and we'll continue to iterate. What I wanted to do with #WarGames is to go in a different direction.

Against the likes of Black Mirror, Westworld, and, going back a wee bit further, The Twilight Zone, there's something fascinating about technology and its ties to horror and dysfunctional society. You seem to be tapping into that here.

The thing that was most interesting to me, and it became the spine of the story, are groups like Anonymous. When you look into those groups, you see this ark where they start at the farther reaches of the internet just doing pranks and awful stunts and it's about the humour and the silliness. At some point they realise that they have power—that these pranks can have real world consequences, and within those groups are those who realise their political power.

I wanted to explore that without going too Black Mirror. In the mainstream press, generally, Anonymous are seen as the Robin Hood-type organisation, the trickster spirit, the guys robbing from the rich. Obviously it's more complicated than that. When we first started #WarGames, I thought about the promises we had from the current round of technology and how social media was going to give a voice to minorities and how a lot of the biases from the real world would vanish in the online world where people were more anonymous. That utopian idea obviously, in the present day and age, didn't pan out. We of course found that existing biases were amplified, we found that minority voices were more easily targeted.

To some extent, I'm interested in exploring that—but not in as direct a way as Black Mirror. It's not fair to say that all technology is evil. That was something I took from the original WarGames movie too—that optimism found in Broderick and Chedi who are sure of the inherent good in humanity. For me that was the heart of #WarGames. If we can tell this story where we still believe that people with their hearts in the right place are going to triumph, that if we believe there is a point to fighting back and resisting—that for me was key.

All six episodes of #WarGames are available. Would you recommend breaking them up, or binging them as we might watch television series?

Yeah, if you watch all six at once, I think it'll be like a long feature. The episodes are around 20 minutes each. I think the best way to watch is to binge it, to put aside two or three hours and then come up for air.

#WarGames is out now on PC via Steam.