Grand Theft Auto 2 marked the end of Grand Theft Auto as a pure chaos sandbox

Reinstall.

Reinstall invites you to join us in revisiting classics of PC gaming days gone by. This time, Marsh Daviesembarks on a two-dimensional crime spree in GTA 2.

Grand Theft Auto 2, released in 1999 by the developers then called DMA Design, was set in 2013—although not a 2013 you'd necessarily recognise. In fact, it's not even a GTA you'd necessarily recognise.

Every other instalment of the series has pointedly evoked a place and a time, gleefully refracted through the multi-faceted lens of crime fiction. GTA 2 marks a loss of focus: a weird sojourn into the pseudo-futurism of Anywhere, USA, a city of perpetual dusk and neon, peopled by clone armies, lunatics, and Elvis impersonators.

That it takes place in 2013 is only confirmed by digging through cross-media backstory bumf on the game's archived website. Elsewhere, one reference puts it perpetually "three weeks into the future" and others place it near the eve of the millennium. The city has its own ideas of when it is: the cars and the arsenal you use to detonate them have a whiff of retro-sci-fi, while the all-powerful corporations, crime networks, cults and clones all suggest a not-quite-cyberpunk tomorrow, more akin to Mega-City One than Los Santos.

In other words, GTA 5 might now look quite different if Rockstar hadn't backed out of the road they turned down in GTA 2. It might even be that they have a slight sense of shame about it: Rockstar have yanked the free download of the game from their website, and delisted it from Steam. Once obtained, it takes a little coaxing to run: I had to set my monitor to 16-bit colour and reduce my resolution, and suffer occasional crashes and a good deal of screen tearing.

It starts with a live action movie—another oddity for a series that has since insisted on in-engine cinematics—starring a young Scott Maslen (Jack Branning to Eastenders fans). Perhaps it was this cinematic aperitif that consolidated Rockstar's stated ambition in GTA 3 to beat Hollywood at its own game, and with a game. It's slickly produced, albeit suffering dated delusions of cool and bearing little resemblance to the cartoonish game that follows.

It's not the only innovation in GTA 2 to be discarded by its successors: the major mechanical difference between this and the first game is the introduction of a faction system. Instead of leading players on a narrative thread, GTA 2 lets you bounce between the three different power groups in each district, fostering trust with one by slaughtering the soldiers of another. At any time you can switch allegiances, building up your trust meter with another organisation by murdering your old allies. Once the respect of one faction is gained, you can access their missions—some of which unlock simultaneously, depending on your degree of respect, others sequentially.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

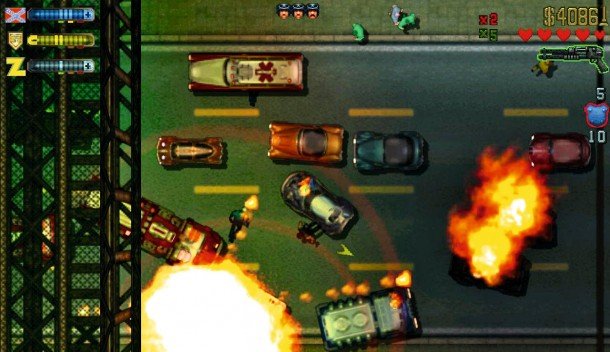

Not that completing missions is even strictly necessary: the end goal is simply to gain enough cash to buy your way to the next district. Early on, completing missions is the most lucrative option, but you gain cash from pretty much any action in the game—a high speed fender bender will get you $100, and score multipliers awarded for mission completion mean that causing chaos becomes an easy means of profit. It's this arcadey vibe that the series has latterly retreated from in all but its novelty side-missions. In Anywhere, USA, anything goes and points mean prizes. There's even a gameshow-style announcer, who bellows out your achievements over blasts of celebratory onscreen text.

It's primarily a chaos sandbox, not a crime story or city simulation, and that's perhaps partly because the mechanics of the game resist anything but mayhem. The driving feels either stiff or overly twitchy, the collision physics makes the cars feel like they're covered in velcro, and the top-down perspective leaves you little time to react as you hurtle along. Erratic, suicidal AI pedestrians throw themselves beneath your wheels, making tussles with the law an inevitability. You have no choice but to embrace these frustrations, ploughing into traffic, detonating pile-ups with glee, and basking in the heat it brings.

In some ways, this arcadey, destructive spirit helps GTA2 avoid that uncomfortable dissonance of later GTA games. It can afford to be blithely, bleakly callous when its civilians are little more than scuttling sprites: hence the joyous reward for running over a conga-line of Elvis impersonators, or the memorably grotesque mission in which you pose as a bus driver, dumping hapless commuters into a meat processing plant to be disposed of between two white buns at a local diner. It's hard to imagine such a thing surviving into the high-definition era.

And yet some things have survived: side missions as municipal workers paved the way for the simulatory aspects of later GTAs, and even the early GTAs prided themselves on their soundtracks full of hot-headed shock-jock blather and wilfully puerile advertisement spoofs. Never ones to resist a good knob-joke, or even a bad knob-joke, mission titles are often terrible sex puns, like, for example, the groaningly obvious Blow Job (it's an assignment involving explosives, you see).

But this humour is scattershot: there's no single thing being satirised here, because the city and the larger world is not a coherent place. The recurring cliché in describing GTA is to say that the city is the main character, but here it's hard to know what that character is. It doesn't really riff on gangsta stereotypes, mob stories, or cop capers. It's not really science fiction or contemporary satire. Anywhere, USA—in 1999, or 2013, or three weeks into the future—is truly a city out of place and time.