Portal is more sinister than you remember

It's known for comedy, but it's even better as horror.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 364 in December 2022, as part of our 'Reinstall' series. Every month we load up a beloved classic—and find out whether it holds up to our modern gaming sensibilities.

Portal has a place in gaming canon that makes it difficult to argue why you should replay it. Either you've played it, and love it, or you know what it's all about. It's like pitching somebody on watching the original Star Wars trilogy for the first time: we all know who Luke's father is. Its iconic moments are part of games culture—the companion cube is almost passé as a symbol of nerd culture, not quite old enough to be retro but old enough to be out of date—and 'the cake is a lie' was more thoroughly memed than 'taking an arrow to the knee' was for Skyrim. And in the meantime, plenty of other games have built on Portal's 'thinking with portals' mechanics, from puzzlers like Bridge Constructor to shooters such as Splitgate

That's before mentioning Portal 2, too, which expands significantly on what the original Portal introduces. About four times as long with additional puzzle mechanics and a co-op campaign, Portal 2 both gives us backstory on Aperture Science and GlaDOS, and introduces the highly quotable new characters of Wheatley and Cave Johnson. Johnson's speech about how 'when life gives you lemons, don't make lemonade, make life take the lemons back' may not have surpassed 'the cake is a lie', but it's printed on many, many tea-towels.

Why, then, play Portal now if its mechanics have been built on by newer games, and its most famous lines have been strip-mined for hilarity and printed on gamer t-shirts for years? Because, I argue, what Portal's position in games canon belies is its effectiveness not as a puzzler, or a comedy, but in telling a horror story about powerlessness.

Test drive

Portal constantly plays with control—and how much or little of it you have at any one time. As the game begins, you wake up in a small glass case which has no exit. All you can do is pick things up in your surroundings: a radio, a clipboard, a mug you can smash. (Which of course, I always do. Resistance may be futile, but I feel it is necessary.) All the while, a camera is watching you—from outside your glass case prison—and a timer is ticking down, while a robotic voice welcomes you to the facility, explaining that "your specimen has been processed" and testing may now begin.

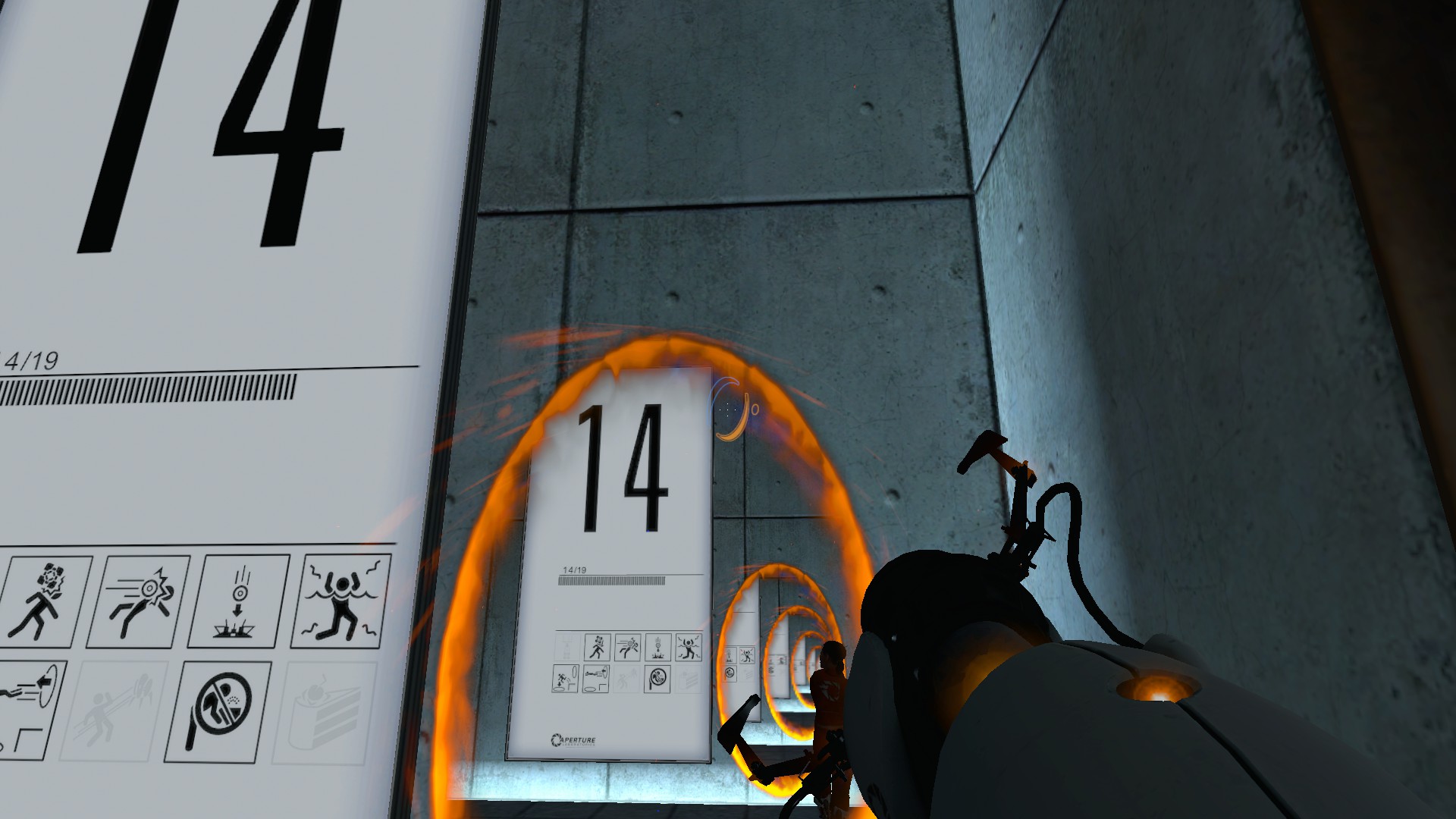

It's easy to forget, but the first tests don't even let you use the portal gun, instead forcing you to navigate around pre-set portals. Even when you do eventually gain full control of both the blue and orange portals, and it feels like the levels should have opened up to you, the level design still feels cold and hostile.

You have to wait for platforms to come to you, for timers to align, for energy pellets to traverse to their destination. Of course it's possible to play it fast—there are both speedruns for 'fastest times' and 'fewest portals'—but there are only set ways you can act on the world. You can press buttons, and you can shoot portals. Trying to rush parts of the test prematurely will at best fail, and at worst get you killed.

The sense of only being a cog in a machine is oppressive—and while the messages are a little off, GlaDOS' presence early on is implied to be that of a set of pre-recorded messages, simply representing Aperture Science. She's the robot you talk to on the telephone while trying to find a real agent, if that robot had the capacity to snipe at you as much as you might want to snipe at it. You're functionally alone.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Increasingly, it's not only the design of the testing chambers that are hostile, but the tests themselves. The floor in one will kill you, so you're warned to try to avoid it. Coming into contact with energy pellets, which ping off at regular intervals, will also kill you. Turrets, armed with laser-sights, will certainly kill you—or at least leave blood spattered up the pristine white walls while you work out how to disarm them.

All the while, GlaDOS offers unhelpful advice, but promises the reward of cake at the other end. Cake, and in one instance, grief counselling.

Even the interstitial spaces between levels are hostile, with the emancipation grills that dissolve any items you try to bring with you (and may emancipate your fillings, crowns, tooth enamel, or teeth), but also the lifts, which are notably lined with padded walls. Invoking psychiatric wards isn't my favourite visual shorthand in horror, particularly when some of the canon background lore for Aperture is clumsy in its depiction of mental illness. Regardless, the imagery is known across too much media to not understand the effect: it's medicalised, and it's isolating.

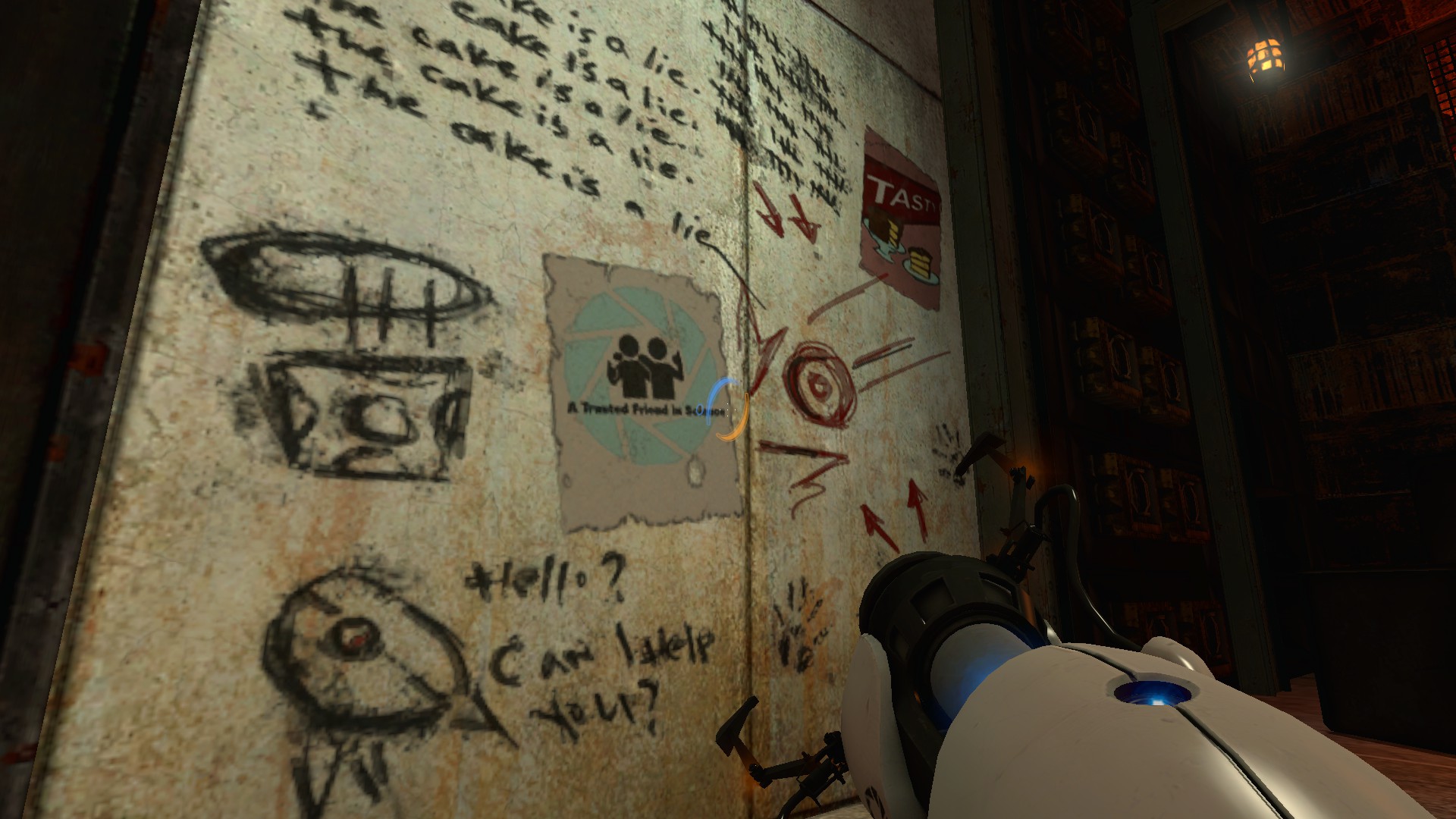

But of course, you aren't entirely isolated, because there's someone living inside the walls, behind the test chambers. In contrast to the sterile, surveilled test chambers, the maintenance areas as you discover them are rusting orange and falling apart—not to mention covered in panicked graffiti. 'The cake is a lie', yes, but also plainly 'help', and if you hadn't picked it up from all the cameras—and GlaDOS's vocal dislike of having them destroyed—'she's watching you'.

The implications of this mysterious figure feed into the sense of threat. What's going to be at the end of testing? If there was going to be a way out of this, why is someone hiding from 'her'? Exactly how malevolent is Aperture, and what are you supposed to do about it? Every handprint staining the wall, every scrawled 'help', is a disruption from the controlled environment of the testing chambers, and a reminder that indefinite testing isn't normal or sustainable.

We remember GlaDOS as funny and mean, but she exists in Portal as a spectre of control. Many of her most absurd quotes ("That thing you burned up isn't important to me… it made shoes for orphans") are only when she's desperately trying to regain it. Until then, she has the upper hand in every situation, and her lines speak of the chilling distance of someone with complete power over your life, but also very little interest in it. "This next test could take a very, very long time. If you become light headed from thirst, feel free to pass out." They wouldn't land the same without the context that also makes them sinister. It's why, out of context, so many of the well quoted parts of Portal only feel like part of tiresome hashtag-random internet culture.

While GlaDOS' jabs become gradually meaner from her telephone-tree persona at the start of the game, the progression from 'this is an institution who doesn't care about me' to 'this is a specific AI who personally hates me' is marked. The shift from 'we, Aperture', to 'I, GlaDOS' only comes when GlaDOS drops the conceit and her narration becomes entirely unhinged. Even then, as much as she insists on party and cake, there are still some chilling lines as you move beyond the purview of her all-seeing cameras. "I know you're there, I can feel you here."

The testing, the surveillance, and the battle for control don't only build to a sense of general dread, but one of institutional horror. Aperture could be a hospital, or a prison, and the trappings would barely change. But in them, Chell is an initially powerless individual, subject to the whims of someone with the authority to say "the difference between us is that I feel pain".

The atmosphere that Portal builds, and the shift in weight between its first and second parts, wouldn't work without how well the puzzles are designed, either. Each testing chamber gradually teaches you how to intuit various skills. When you might need to use conservation of momentum to fling yourself to a great height or distance, or how to time portals to go around lethal obstacles, or even the simple training to look for light tiles.

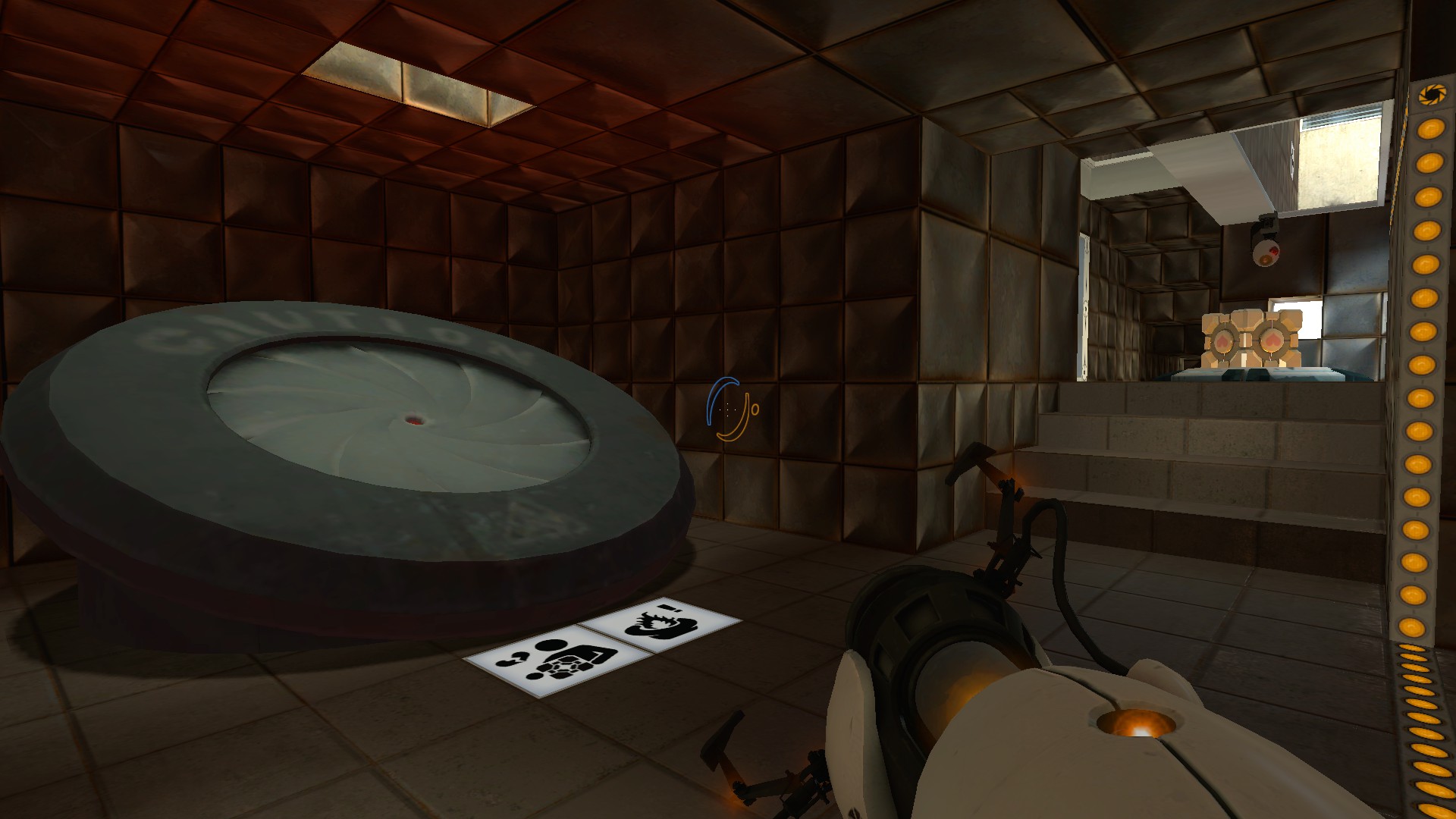

When you find yourself outside of the testing chambers, you're no longer being asked to test, and these abilities become survival skills. It's still all puzzle design, of course, but without the visual cues of test chambers—the step markers, the clearly marked entrances and exits—you're forced to think on your feet. If the first half of the game is hostile because the chambers feel designed against you, the rest of Aperture isn't designed for you at all.

Box art

Portal is funny. GlaDOS is ridiculous, the jargon for 'cube' and 'button' is excessively over-the-top, and turrets say 'ow' when you knock them over. But it's as funny as it is because it goes to such dark places. Portal 2 sets this darkness aside for more gag-based comedy and a jilted-ex dynamic with GlaDOS—which I can appreciate on its own merits—but it also cements the Portal series as one remembered for its comedy. In the years since its release, the details contributing to its atmosphere of oppressive discomfort are flattened.

In under three hours, Portal uses the time it has to not only teach you exactly how to play it, but also to notch up tension until the necessary moment where it breaks. It's effective for horror and a punchline both, with no room for emotional fatigue. It's worth reinstalling for that experience specifically: of a short, creepy game, that's clever and not bloated, and plays with the fine line between sinister and absurd.

Before booting it up again for this piece, I'd last played Portal only two years ago. Judging by my screenshot library—and memories of who exactly I've bullied into playing it—I've played it every two to three years since it was new to me. The puzzles are burned in muscle memory by now, but the interval is just enough time for any inoculation I had against the creepiness to wear off. 'The cake is a lie' might be a well-worn joke, but the help painted onto the floor in the same area is unsettling every time.