Picking every fight in Mirror's Edge, part 1

Can you stand your ground in a game about momentum?

This diary was originally serialised in PC Gamer magazine. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US. You can read part two here, and part three here.

Mirror’s Edge is worse off with guns. That’s the received wisdom, anyway. The theory goes like this: DICE, upon inventing the running simulator, panicked a bit. Any new series is a challenge for a AAA developer—a cacophony of newness, where a sequel builds on past successes. And this game, more than most, was an expensive unknown—one that stripped away the familiar paraphernalia of first-person games. Sticking Colts and SCARs in Mirror’s Edge was a way of anchoring it in something safe. The guns represented reassurance, both for the Battlefield developer and an audience it worried wouldn’t quite get it.

1. Whenever somebody attacks Faith, fight back.

2. Take every possible opportunity to use the guns.

3. Only run once all other options have been exhausted.

Perhaps the studio was right to be worried—Mirror’s Edge didn’t sell particularly well by EA’s standards. But a core fanbase really, really got into it. They understood it was a game about momentum, and that the guns were antithetical to that goal. They encouraged you to slow down and take aim, breaking the pumping pulse the game offered at its best.

People never really stopped talking about Mirror’s Edge, and when the time came for DICE to have another crack at the series, it seemed to agree with the consensus. For Mirror’s Edge Catalyst, the studio changed almost nothing about the pace or moveset of Mirror’s Edge. But it got rid of the guns. In its place, DICE designed a melee system that would capitalise on momentum. You could gather speed, spring off a wall, and plough all that force into the face of an enforcer. A suite of attacks was built to weaponise your catalogue of slides and spins. The idea was that you would use your enemies’ armoured weight against them, sending them stumbling into your waiting foot for a roundhouse finisher.

In practice, most players weren’t particularly hot on that either. In the wake of Catalyst, combat is still considered the weakest element of Mirror’s Edge. I’m left wondering if we gave up on the guns too soon? What would a combat-heavy run of that first game feel like?

Kick! Punch! It's all in the mind!

I’m going back to The City—to the time before it gained the addendum “of Glass”. I’m going to play through 2009’s Mirror’s Edge and take every possible opportunity to start a scrap. Wherever there’s an option for fl ight, I’ll pick fight first. In each instance, I’ll keep firing until the enemies have all fallen over or the ammo runs dry—whichever comes soonest. Faith might have got us this far, but it’s time to meet Fury.

I’m on a job. The runners in The City exist in the membrane between civilised and criminal society. They’ve opted out of the safe-yet-controlled culture down below, but stay sufficiently distant from real trouble that the police leave them alone. That precarious position limits their career options to, essentially, private postal work. And so today I’m carrying a bag across the rooftops to a comms tower, where another runner, Celeste, will take it to its destination. I’m hoping the package doesn’t have a “this way up” on it—I’m doing a lot of forward rolls.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Something unusual has happened, though. A news helicopter has tipped the cops off about my building- hopping activities. I suppose eventually a surveillance state polices itself. So much for living carefully on the mirror’s edge—looks like I’ll be putting my violent new set of rules to the test imminently.

Sure enough, when I drop through a vent into a high-rise intended as a shortcut, I find four cops waiting for me. Bullets follow my footsteps as I jog awkwardly into cover and survey my options.

The space I’ve just left is a small anteroom, in which the men with guns are no more than ten metres away. But as I turn the corner I find a stairwell, and a tall bank of lockers. I clamber on top, waiting for my pursuers to pass so I can hop down behind them.

If I’m going to pull this playthrough off I’ll need to get used to disarming enemies—and that’s far more easily done when they’re facing the other way.

But no plan survives contact with dystopian reality. Philip K. Dick said that, probably.

When I slip behind the last cop to storm past my hiding place, he turns around at the last second, pushing against my shoulders. His colleagues open fire as I stumble, and I drop to the fl oor. This is no typical DICE shooter—Faith can only catch three or four bullets before taking a long lie down.

On the second attempt, I manage to plunge off the lockers and land on an enemy, Mario style, knocking him out. But when I reach triumphantly for his weapon, nothing happens. I can only see a baton on his waist—but I could’ve sworn he was firing at me just moments ago. Bewildered and blocked in, I run back the way the cops came and stare impotently at the anteroom’s vending machine as red fills my screen. “Digglers doughnuts,” reads the advertising. “Because life is sweet.” My view turns on its side as another bullet enters my back.

After a few more tries, the game crashes to desktop, as if in protest. “You should always try to get away from hostiles,” Mirror’s Edge’s tutorial tells me. The info box shows an image of Faith running towards a SWAT team—and then a big, red arrow bending in a U-turn.

My handler Mercury—like the messenger god, or Merc to his friends—joins in by yelling over the radio. “Wire’s going crazy, get out of there, Faith.” Even the cops physically push me onward, like actors in interactive theatre. This isn’t supposed to be a combat encounter. It’s a prompt for a chase, to propel me through to the next area. Everything in the game is screaming at me to run, and I’m working against its nature.

If I’m going to control the situation, I’ll need more space. I lead the police up the stairwell, looking back every few seconds to make sure they’re still following, like a cat teasing a dog. Using the Mario technique, I’m able to use my height advantage to pounce on the cop at the front of the pack as they round the corner at the top of each staircase. I take out three this way, and shepherd the final officer out onto the rooftop.

Here I can play to my strengths. I sprint down the far end, where my opponent’s bullets become distant annoyances. Then I spin around, ready to charge him like a jousting knight. Until a door crashes open on my flank, and two more cops shoot and shoot and shoot until my light frame is heavy with lead.

Repeating the sequence using the few close quarters moves available to me is gruelling and unsatisfying work—especially knowing that more forceful tools are, for reasons unknown, just out of reach. On the next attempt, though, I manage to take out the entire first squad on the stairs. Thumping trance escape music still plays, but it’s quiet on the roof. This time I’m ready for the door to open, and kick the first cop in the shins. He doubles over in pain. The second opens fire as I retreat, nicking me in the shoulder, and I notice my palms are sweating as if I’m fighting a Dark Souls boss. Every time I stand and face my oppressors, I’m at a terrible disadvantage.

But then, as the first cop falls unconscious, something changes. Amid all the familiar smacks, grunts, and booms, a new noise—the clack of a metal object against a hard surface. A gun. Barging past the goon in my face, I pick up the pistol and let off a few rounds into his chest. It’s an ugly spectacle. There’s no action movie feedback, no ragdoll pinwheeling across the terrain—just a man slumping onto concrete. I swap his loaded gun for my empty one, and run on.

Before long I’ve developed a nasty pattern—shooting a cop dead wherever they rear their masked head, before swapping my weapon for the one they’ve left flush with ammo. There’s no way to know how many bullets I’ve got left: in accordance with the style of the time, Mirror’s Edge rejects UI altogether, leaving the screen empty of distractions. But the pistols tend to click uselessly after just a handful of shots, and there’s no way of storing clips, so I’ll need to find new guns regularly if I’m to stay armed.

I murder my way to the comms tower, where my partner Celeste awaits. “They’re playing rough, Cel,” Faith warns as she hands the bag over. Back in Mirror’s Edge’s day, this is what we referred to as ludonarrative dissonance—the disconnect between a game’s script and the way you play it. If the cops are rough, I’m playing far rougher.

Smashing the mirror

You can learn a lot about a game by breaking it. I’ve played Mirror’s Edge for years, but only by opting out of its constant forward momentum have I started to appreciate how it works. It’s not just the rooftop furniture of the game’s levels that are designed to boost you forward—every successfully landed wall jump or pipe vault adding to your acceleration. The same is true of the script, the soundtrack, and the enemy placement. All of these elements are deployed with careful timing to provide the wind for your sails, a series of convincing reasons to keep running all the way to your endpoint. I’ve every reason to believe that the devs at DICE would make fantastic personal trainers.

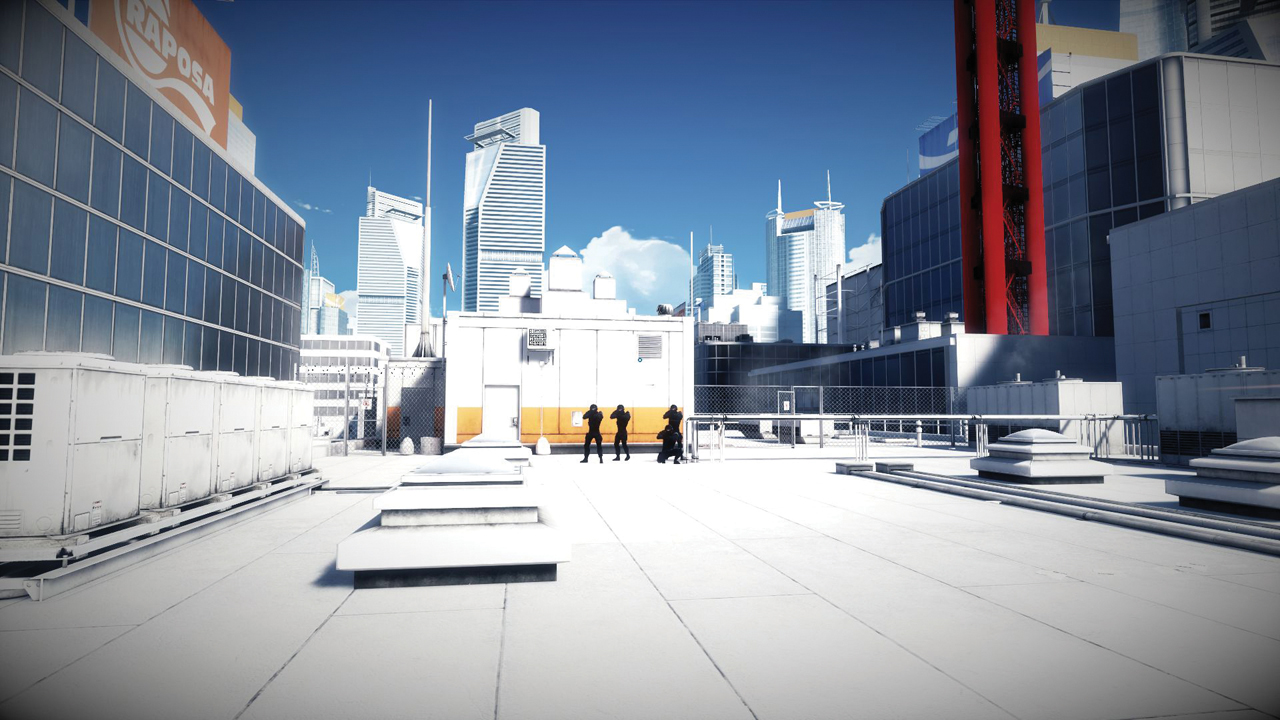

As I leap to this level’s final rooftop, I can see how it’s supposed to go. The news chopper, having made its story happen, is here to film it. A SWAT team arrives stage right, intended to funnel me over the lip of building. The helicopter draws level with the roof, its nearest landing skid glowing red—a sure sign, in Mirror’s Edge’s colour- coded world, that it’s part of the path.

“I don’t care how you get off that roof, Faith,” Merc prods. “Just do it.” These Truman Show- esque performers aren’t opponents at all.

They all want me to do the same thing—flee from the SWAT, their bullets raising this moment to dramatic climax as I leap for the rail of the helicopter. Fade to black, next level. But those aren’t my rules. I’m going to have to fight.

The rooftop is designed for a quick escape, not for hiding, but I use the sparse cover offered by fans and pipework to lure the enforcers into open space, darting out for jabs when it’s safest. If I was a playtester, DICE’s designers would be swearing quietly over my shoulder.

Just once I glimpse a flash of red—an opportunity to grab an assault rifle—but I miss my split-second window. Instead I manage to slide-kick and side-swipe my enemies senseless, leaving a strange silence. The news copter still hovers obediently in the air. I’ve given them one hell of a broadcast and with all of us at the mercy of this new playstyle, there’s no telling what’ll come next episode.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.