Remember when overclocking actually meant something?

Meaningful overclocking in PC gaming is no longer A Thing.

I'm sat in some indoor karting arena just off the Las Vegas Strip, drinking piss-weak beer from a plastic cup, idly prodding at the same kind of browny beige food I've seen at every press event this week. Hell, for all I know it is the same food. Just scraped off discarded plates, dusted down, and warmed up again. The world's never going to miss a few more tech journalists dying of salmonella after all.

It's bloody loud in this echoing warehouse, with the electric whine of kart motors filling the dusty air, backed by barely perceptible music beating a grinding rhythm behind it. But every now and again the volume picks up, with an excited sting of techno you couldn't even dance to at 4am on a Welsh hillside with a crushed can of cider in your hand.

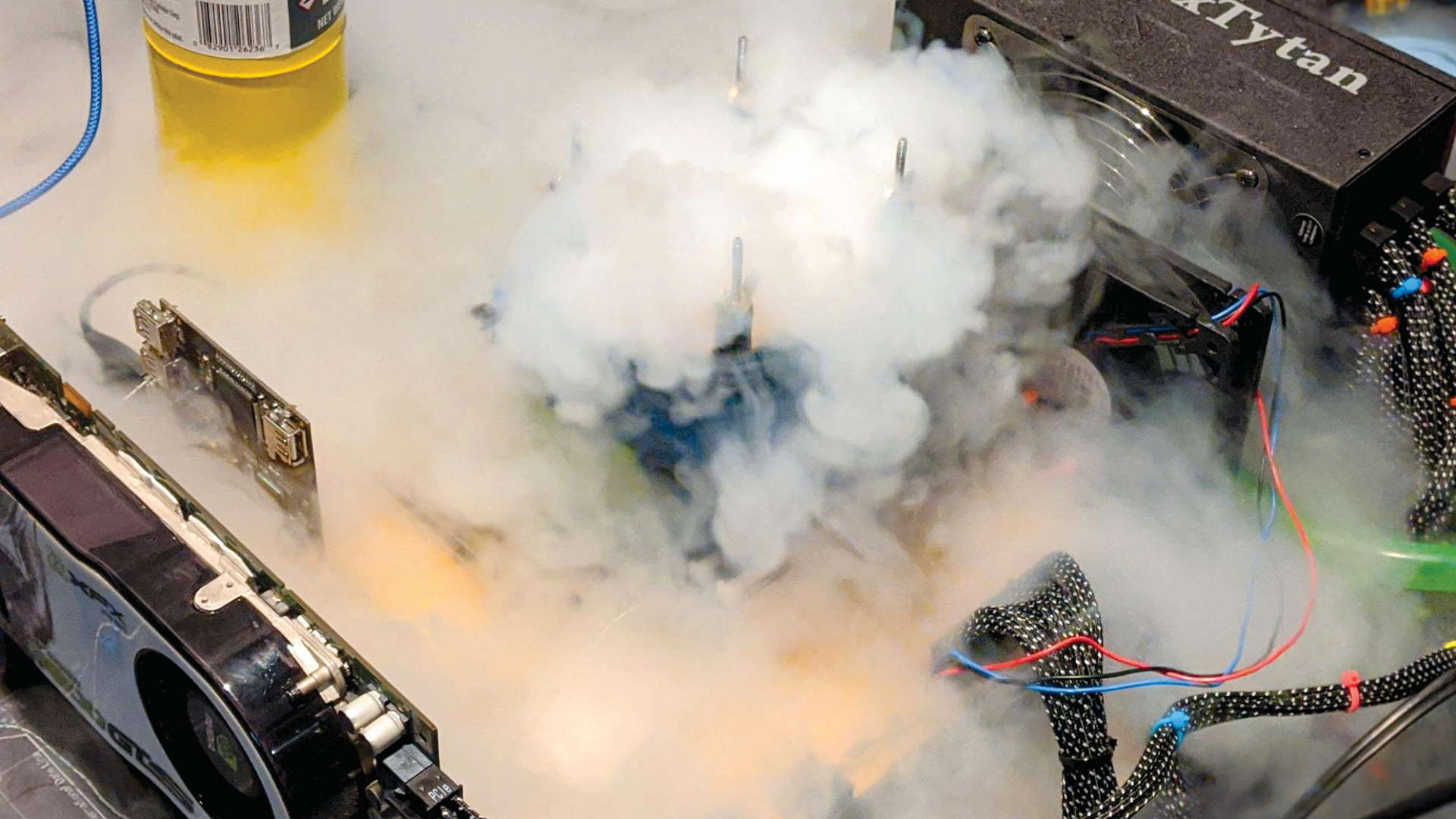

The digital lap timings board has been taken over for the evening by whoever set up this CES overclocking event, and every ten minutes or so another "World Record Breaking Overclock!" is announced. The ever-higher, and frankly meaningless SuperPi or Geekbench numbers are shat out onto the big black board in fat red pixels, alongside a jumble of characters which represent the nom de plume of the dude who poured some liquid nitrogen into a cup balanced atop a CPU and clicked 'run'.

Or maybe they're 3DMark index numbers and the tweakers are hosing down GPUs with LN2 instead. Whatever, it's all hitherto unreleased hardware and all likely to be quickly surpassed once these products find their way out into the wilds of the extreme overclocking community.

This isn't overclocking anymore, this is just marketing

At this point I'm past caring and desperately trying to figure out why I'd agreed to step so far off the Strip to see a bunch of professional overclockers try to one up each other for their corporate sponsor. It's been a busy, long CES week; I only really came here to mess around in a tiny car, and I've already had my one allotted lap of the track.

And the rapidity with which another "World Record Breaking Overclock!" occurs also has me doubting the legitimacy of this whole smug race track/overclocking conceit.

It all feels so pointless, so far away from the classic, pure ethos which gave birth to overclocking. Sat here, watching PCs barely stable enough to post, being put through exceptional, unsustainable torture just to see a slightly higher number from an unsatisfying benchmark, I despair. This isn't overclocking anymore, this is just marketing.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

That was a dejected Dave at a CES overclocking event just a few years ago. But, looking back now, this is exactly how I feel about pretty much all overclocking today.

PC overclocking of old

I don't want to lean into my curmudgeonly old man persona too hard, but overclocking used to simply be about trying to squeeze the most performance out of your PC gear because you couldn't afford to spend hundreds of dollars on some newer slice of silicon. It was about normal PC geeks doing whatever they could to push their machines to perform faster, to squeeze just a little more power out of the modest components they had to hand, and then sharing their experiences to help others.

It was never about spending big on (or now often being sponsored with) the biggest and most expensive kit then pushing it further for some ephemeral numerical advantage over the competition.

Even in recent history—though not as far back as the super old-school drawing pencil lines/superglue on a chip kind of overclocking—it was all about mid-range CPUs and GPUs that had significant clock speed headroom, and could deliver permanent, tangible gaming performance boosts if you were willing to put in the time and effort.

For generations of Core CPUs you could guarantee Intel's chips would deliver at least another 1GHz on top of their base clock. It was almost part of the review process back in the day. Could the latest CPU offer another ~1,000MHz? Yes, good. Next. And with some patience and perseverance both ATI/AMD and Nvidia's graphics cards could produce a clutch of extra frames per second that would turn an unplayable game into a joy.

The classic Intel Core 2 Quad Q6600, for example, would regularly overclock by around 1GHz from its lowly 2.4GHz origins. That was just in the hands of the general, buying public too, not with the extreme hobby overclockers. And in solid, everyday systems too, ones that could game with that overclock all day long and not suffer.

Pushing the quad-core Intel chip up to around 3.4GHz would net you anywhere up to 18-20 percent higher in-game performance in pure frame rate terms, resolution and GPU depending. That's 20 percent more raw gaming speed for free and, while it's become a classic chip, it wasn't such a rare beast.

Then Intel locked down multipliers on its chips so it could sell specific SKUs for overclocking and stop anything quite like the Q6600 happening again, a chip where you could get the same performance as a CPU that cost three times the price for the cost of a decent air-cooler and some of your time.

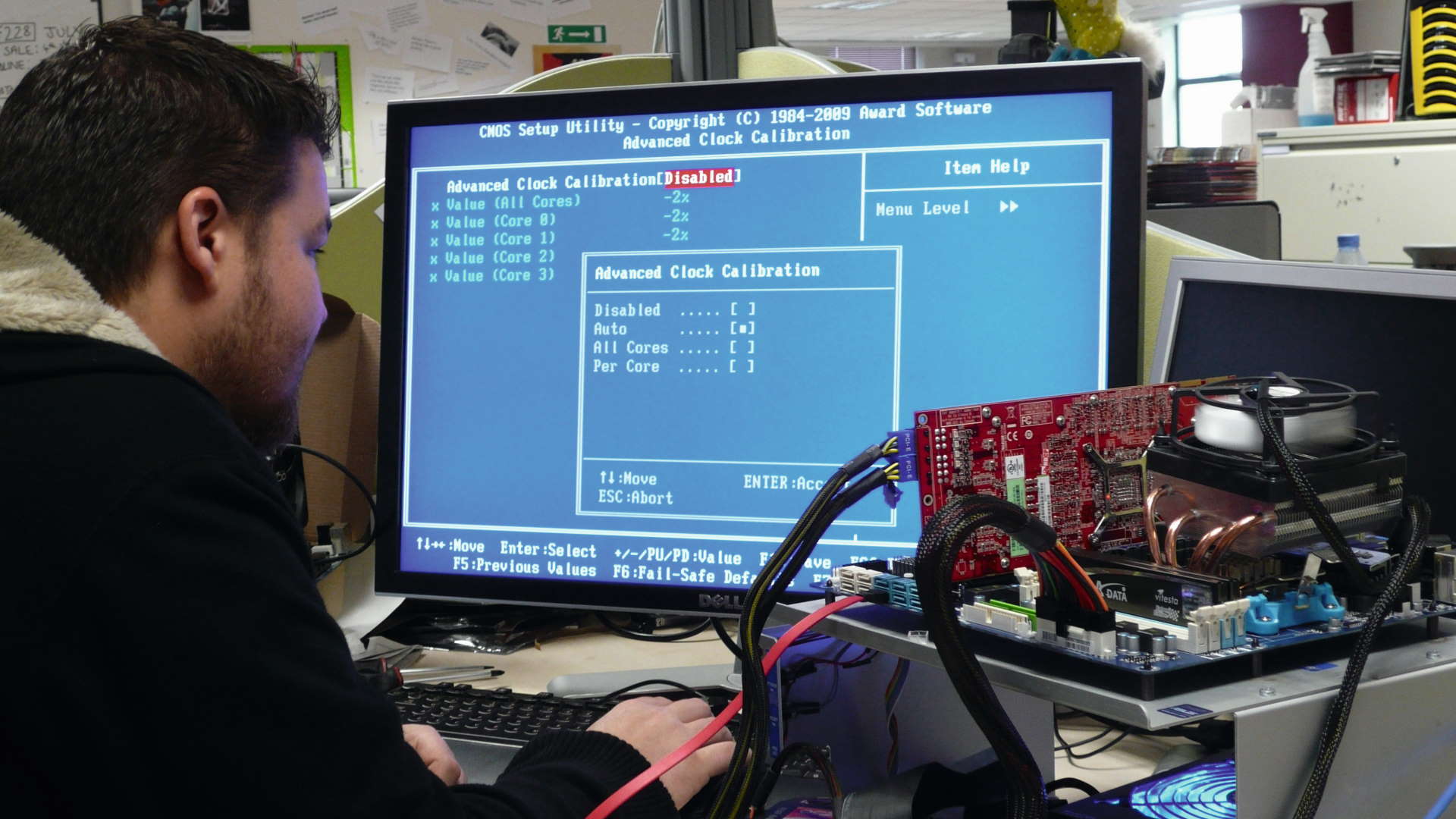

But even as recently as the Kaby Lake range of Intel processors I was confident of squeezing another 500MHz out of my Core i7 7700K. Though it was already becoming obvious that was having very little direct impact on gaming frame rates.

And now Intel is having to squeeze every last drop of blood out of the 14nm stone with each successive CPU generation, so there is very little headroom left for the overclockers out there. On the AMD side, since Ryzen, it's been tough to get anything beyond the rated clock speeds out of the red team's processors, as it is now for Intel too.

Basically, today's PC hardware is already running at the ragged limits of its design straight out of the box, leaving almost nowhere for us normal folks to go with our silicon. Sure, you can add a little on to modern CPU and GPU frequencies, but across the board it makes little difference in-game. Not even the stock 10 percent frame rate hike you could rely on from a quick overclock just a few years back.

Sadly, with overclocking now at its least necessary, it's easier than ever to safely tweak your own PC tech. Intel and AMD have excellent chip boosting software, and Nvidia's last two generations of GPU have an auto-overclocking lever you can pull which will configure your specific chip with a frequency/voltage curve tuned to your exact silicon. That will give you a great starting point, but still won't result in any higher frame rates.

Dynamic chips and better manufacturing

Part of this is down to the more dynamic nature of CPU and GPU clock speeds these days. Rated frequencies are now only ballpark figures, with the given silicon making up its own mind about how far to push clock speeds given the thermal headroom available to it at any given time.

Efficiency and thermals are the key pieces of the performance puzzle now, which arguably makes undervolting the new overclocking. I got way better performance out of my beloved AMD RX 5700 after unlocking and undervolting it than overclocking it, simply because I could push the voltage way down, leaving more headroom for the GPU to do its own thing... but that's for another article.

This is why we've seen many occasions recently where, even though we've manually forced a higher GPU clock speed ourselves, we're actually seeing lower gaming performance than at stock settings. Run a chip at a higher rate from the off and it will often hit a thermal ceiling, and start throttling back, far earlier than if you just left it alone.

Overclocking the Nvidia RTX 3080, even using its own OC Scanner auto-overclock button sometimes resulted in lower frames per second scores in games. Yeah, the 3DMark numbers are higher, but frame rates, even down at the 1080p level, barely show any positive movement.

It's largely the same story with the AMD RX 6800 XT, where even its aggressively titled 'Rage Mode' actually saw frame rates drop as the chip was given a supposed speed bump.

You can argue this development is down to improvements in manufacturing, with less of a silicon lottery, and chip makers now able to be more confident about shipping high volumes of high-performance silicon pushed to its peak potential speed. Which is fair, and I'm not for one second blaming the likes of AMD, Nvidia, and Intel for not wanting to leave any performance on the benchmark table. But it doesn't change the fact that in real-world gaming terms overclocking is as dead as the hearty handshake.

Don't get me started on factory overclocked graphics cards. They're the actual worst. Paying another couple hundred dollars for an extra 70MHz and no extra actual performance does not a great experience make. Though at least you might get a nice, quiet cooler for your extra cash…

Style over substance

So, where does all that leave the once great state of overclocking? Sadly, I worry it's now in the hands of the marketing departments. Overclocking is now seemingly used as a small check box on a product marketing spreadsheet; a way to push up the price of a component by making it 'for overclockers' without really having to worry about delivering higher real-world performance.

None of these hardware companies would be as willing to sponsor them if it weren't for the fact that liquid nitrogen just looks so damned mad science cool

Or it's about just the image.

Pre-pandemic there was not a CPU launch event or trade show that wasn't lousy with professional chip tweakers doing live demonstrations, overclocking the latest silicon of their hardware sponsors.

There is undoubted skill involved in squeezing the last few index numbers out of a CPU benchmark before it catastrophically falls over, but I would wager none of these hardware companies would be quite as willing to sponsor them if it weren't for the fact that swilling liquid nitrogen around components just looks so damned mad science cool.

The massive tanks of LN2, the gloves, the protective goggles, the layers of frost, and of course the plumes of steam, all add to the theatre. That, almost more than the big GHz numbers themselves, is why overclocking has become a marketer's silicon soggy dream.

There will of course be those folk, high on LN2 fumes, who will protest furiously that the independent overclocking community is most definitely alive and well in 2021. That you only have to look at the HWBOT boards to see people are pushing the latest Nvidia graphics cards and AMD processors beyond the bounds their makers have set.

And it's true, if you want to slosh some extreme cooling element across your chips then you can far exceed the rated specifications of pretty much any hardware around right now. And you'll likely see some higher 3DMark index scores or SuperPi numbers.

If that is what you want to do as a hobby, who are we to judge? Well, right now there may be a few folk out there resenting the punishment you're putting new graphics cards through in your search for fleeting leaderboard fame, especially when people who want to use them for gaming are unable to find one in stock anywhere. But that's a separate matter.

My issue with the hobby overclocking is that it's utterly removed from actual PC performance. It's not tuning a system so it can run at its peak, and none of it is done to make any difference to your actual day-to-day PC experience. You can't run a gaming rig on LN2 permanently. It doesn't work like that.

The world record-setting style of extreme overclocking is all about impermanence. It's a short-lived peak that is absolutely impossible to sustain, and more about the number alone, not what it means in PC performance terms. That makes it irrelevant to any normal gamer, and maybe just a game in and of itself.

Which I guess is fine for a standalone hobby, but, to me, it's not really overclocking in any meaningful way; it's just some sort of borderline obsessive benchmark numberwang.

That still won't stop manufacturers from shipping their latest hardware out to extreme overclockers to try and garner some sort of halo effect for marketing. Or wheeling them out at events to do shots of LN2 live on stage. Or claiming in pre-release materials that this is somehow their finest overclocking silicon. Or indeed naming specific SKUs to suggest they're going to be superior for gamers because someone once splashed liquid nitrogen on one.

But for the rest of us, us normal PC gamers looking to get the most out of their existing hardware, those trying to get the latest system-pushing software to perform better on their own rigs, overclocking is over.

Dave has been gaming since the days of Zaxxon and Lady Bug on the Colecovision, and code books for the Commodore Vic 20 (Death Race 2000!). He built his first gaming PC at the tender age of 16, and finally finished bug-fixing the Cyrix-based system around a year later. When he dropped it out of the window. He first started writing for Official PlayStation Magazine and Xbox World many decades ago, then moved onto PC Format full-time, then PC Gamer, TechRadar, and T3 among others. Now he's back, writing about the nightmarish graphics card market, CPUs with more cores than sense, gaming laptops hotter than the sun, and SSDs more capacious than a Cybertruck.