Minecraft - PC Gamer UK's Game Of The Year

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Can you dig it? Yes you can. Twelve months of getting square eyes with Minecraft.

When we each made up our personal list of favourite games this year, Minecraft was on nearly all of them. It's a first-person fantasy game made of cubes. There are cubes of grassy soil stacked in contours to form mountains, smooth cliff faces that you can dig square tunnels into with your voxellated pickaxe, and cubic trees sprouting cubic leaves. Your head is a cube. The sun is a cube. In all probability, the world of Minecraft is a cube. You should also mentally cube the length of time you expect to spend in it, because it's so stimulating and relaxing, so hypnotically compulsive, that you'll never escape its grip.

Minecraft started off in May last year as a Java-based curiosity that generated some blocky terrain and let you explore it. You could wander the bright grassy world, encounter gentle hills and the odd stony cliff face, and that was about it. Then Markus Persson, its sole creator at the time, added the ability to destroy and place blocks of any type. Then he added water and lava, and improved the terrain generator. He let you save your map, and then share it with people. Communities of friends would take turns adding landmarks and buildings to a saved game and writing diaries, trying desperately to play and build together in some meaningful way.

Skin deep

Around July 2009, when I started playing, Markus had just released Multiplayer mode. Players who'd supported development by preordering the finished game for £10 were allowed to wear a custom skin. I got my wallet out. I remember thinking, 'I've just spent £7 for the privilege of editing a tiny pixellated image so I can look like a douchebag in a free computer game.'

My first experience of Minecraft was what's now called Minecraft Classic – you can pick from a broad pallet of blocks, place as many as you like and destroy them instantly, and you're invulnerable to damage from water and lava.

I joined a server with four people on it. They were building a castle, and talking about it in chat. I built a tower a little way off to watch them, but soon I got engrossed in the intricacy of creating it. I built a staircase around the stem, a viewing platform on top, and then I crenellated the shit out of it until it became a lighthouse. By then the castle was done, and they'd started work on a labyrinth beneath it and a village in the next valley, by the river. Satisfied with my work, I went for breakfast and returned much later.

Disaster. Griefers had struck the server, exploiting an early bug that allowed them to flood the map with lava, building horrible thin towers, and placing and destroying blocks wherever they could. It was three dimensional white noise in all the colours of the rainbow. I hopped between the walkways over the lava and tried to find the castle. I discovered the remnants of the labyrinth beneath it, now flooded. Nearby, I found my lighthouse.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Stumbling block

They'd destroyed everything they could reach, but they hadn't been methodical enough to climb it and destroy the top first, so there was just a floating lighthouse. I connected it to the remnants of the hill I'd built it on – the only surviving scrap of natural terrain – and made it look like a ruin. Then I cried myself to sleep.

When that bug got fixed, the griefers just did it with water, and when that got fixed, they could still destroy blocks. It was better to play with friends on a secure server, or just to play by yourself, than to build on a public server and risk having your work riddled with holes as you slept.

As modders began to get comfortable with Minecraft's Java anatomy, powerful server tools started to appear that dealt with griefers. Soon, it was possible to give players tiered building privileges, and Minecraft Classic became a civilised place. It even got its own sport: spleef, a game of digging the ground out from under your opponent so they fall into a prepared Pit of Shame.

Then, around August 2009, Markus released an in-development preview of Survival mode. This was available only to users who had paid, and introduced resource management, monsters and, eventually, crafting. You cut down trees to make a crafting bench, and use that to make tools and other furniture. As if you weren't dying to make a castle already, it gives you a good excuse to have a central hub for your crafting activities, and to pretend you're building a house.

Go for goal

Before Survival, you were happy to just make any old thing that looked nice. Now you're playing a game. Suddenly, that little cabin you made is important. Can zombies fall onto the roof from that cliff up there? Will spiders slide out of that crack in the mountain face? Now you have goals and objectives. You need to get some sand to make glass so that skeleton archers can't skewer you through the windows. Now you need some coal to make torches to ward off the undead while you're mining.

But of all the monsters that crept up in Minecraft, the creeper is the most distinct. It's a tall green quadruped with a permanent frown. Creepers hop around the landscape in small groups, and when they see you, they start to hiss and hop after you. When they get close enough, they puff up, flash white, and explode – destroying a huge chunk of terrain. They're quite scary, but also a little bit cute.

Only a few of us knew about the game at first, but as Minecraft's grip tightened on the office, we began to evangelise. “Hey Tom, look, I've crafted a pickaxe and I'm using it to hew a path into this cliff.” “Hey Rich, I'm channelling water down into that lake.” “Hey Tim, you can fill a mountain with TNT and blow it up.”

It starts to make you go all funny. My first castle was a 5x5x10 keep with barely a window in it, but every time you decide to fortify something, you'll make it bigger and grander than the last time. When you flatten a mountain and build a wall around it, then build a keep inside that, then build another wall all around that, then a palisade surrounded by a trench and then a fence, and hundreds of peasant houses and farms for miles around, you realise you're playing the game of the year.

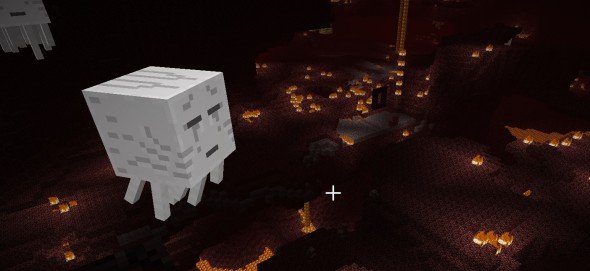

It revolves around the same irresistible creative urge that made Lego king of the bricks-for-children industry, but it stays fresh because Markus Persson never stops making Minecraft. Survival mode already had crafting, so he kept adding recipes. This one time, he added boats. He added snowy maps, and you could throw snowballs at the monsters. He added mine carts that you can ride around in. He added secret underground dungeons, with loot and monsters. He added an ore that can be made into wires and combined with other elements to make logic gates. He added doors and fences. He added a dangerous fiery dimension that you can use to quickly travel around your main world via evil, purple, fiery gates.

But the Minecraft community has a list of achievements and bizarre creations just as long. Whether you're importing the schematics of the USS Enterprise into a Minecraft map, using some sort of fan-made editing utility to build a working Arithmetic Logic Unit out of the game's conductive Redstone wires, or just spending most of your adult life building an evil death castle where two treacherous mountains form a narrow pass, Minecraft will turn you into an obsessive architect.

Gold mine

The dream was always Survival multiplayer, though. Fending off monsters with your friends by night, building a castle by day? Oh yes. Right now, you can play a buggy version that renders players and monsters invulnerable, which entirely thwarts the premise of a survival challenge, but there are still restrictions that make it worthwhile. You can't just build castles like a lunatic anymore – you've got to mine those materials first. In some cases, that involves chopping down trees, or turning a cliff into a quarry. For glass, you need to stick a lot of sand in your furnace; for more exotic materials, you need to go deeper underground. Like the early Survival build, it adds meaning to your mansion.

Minecraft sits among the very best of games, just because you can play so many games inside it. It's a philosophy taken to its natural conclusion in glorious software. It's a primal urge – to build a goddamn hill fort – in gaming form. Markus has sold enough copies to create an army of bricklayers. This is why Minecraft is the game of 2010.