Our favorite video game lore

Lore! It's that wonderful bedrock, running miles beneath the plot, holding up a story's heroes with myth, legend, and extremely detailed accounts of 200-year-old trade routes and the great fish famine of 144X. While the word typically refers to ancient traditions and folklore, we've come to use it to describe all the stuff in games that establishes a convincing world with its own history—details you don't really need to know, but are worth knowing.

A few of us here have chosen our favorite tomes to celebrate here. Let us know what fictional history you've gone spelunking into, and the most interesting details you returned to the surface with—like that Warhammer's Space Marines spit acid and eat brains.

Portal

By Chris Livingston

Portal could have easily gotten away with just being a series of cleverly designed test chambers narrated by a scathingly funny overseer and solved using an immensely fun tool. And for a while, that's what it felt like, a fun and entertaining first-person puzzle game. Eventually, though, cracks began to appear—literal cracks in the facade via malfunctioning wall panels which offered brief and intriguing glimpses behind the scenes. We found messages scrawled in hidden areas, written by a seemingly disturbed escapee, and began to learn more about the state of world outside Aperture thanks to a few references dropped by GLaDOS, including hints that tied into Black Mesa and the larger Half-Life universe.

This continued in Portal 2, where we essentially got to travel back in time to view the original facility, learning in bits and pieces how it came to be, hearing the story of Cave Johnson (in his own nonsensical yet no-nonsense pre-recorded words), the origins of the Aperture Science (they used to make military shower curtains), and even gave us evidence of how Chell came to be there in the first place. This gradual backfilling of story, both through the game's writing and in the environment itself, wonderfully complemented the puzzles and gave players a chance to solve something more than just the next test chamber.

Dota 2

By Chris Thursten

Dota 2 doesn't need lore. Your heroes are pretty little bundles of numbers, acting out an eternal war across a battlefield that is more football pitch than dramatic stage. Those heroes are themselves derived from characters based on characters from an entirely different game. This could have simply been a blurry second photocopy of WarCraft III, and that would have been both disappointing and fine.

Valve didn't do that. They've applied some serious authorial effort to Dota, creating a fantasy world that is funny, subversive, and subtle. Brilliantly, the character of each hero is drawn from the way they play, and the cult of personality that grew up around them during Dota's time as a mod. Pudge is brutal but silly, as he tends to be. Axe is having the absolute time of his life. Enchantress is naive but, when it comes down to it, terrifying.

There are some brilliant ideas and secrets buried in there, too. The four Fundamentals and their fractious relationship with one another. The implied bad blood between Magnus and Alchemist, Rubick and Invoker, Treant Protector and Timbersaw. The wheel-books of the Ruined City, that turn in the wind to whistle prophecies; whatever truly happened to Kunkka during that final encounter with Tidehunter; Tinker and the Violet Plateau incident, a fantasy mirror for the plot of the first Half-Life. All of this told through a few paragraphs, a few item descriptions, a few in-game one-liners. Dota 2 doesn't need lore, yet it's better than it has any right to be.

Dark Souls

By Tom Senior

Dark Souls lore is special because it's full of holes. The story of the gods' war against the dragons, the dark, and each other is never expressed in continuous prose or expository conversation. It's broken into tiny pieces, and scattered all over the world in item descriptions, architectural motifs and the cryptic statements of half-mad NPCs. You piece it together slowly, like a detective.

Game lore is almost always immutable. Writers tend to structure worlds around a succession of historically certain events. Characters may have different opinions about those events, but they absolutely happened in the way that the lore text describes. Dark Souls rarely provides that level of certainty. You have to grapple with an impressionistic sense of what might have taken place. Sometimes, sources conflict or contradict one another—all of Dark Souls' narrators are unreliable in some way. DS lore the rough, uneven texture of ancient history. It feels authentic.

It's a tragic history, too. You have to feel for Gwynn who, faced with extinction, seems to have committed some terrible acts. There’s so much to consider. What if the Witch of Izalith's plan had worked? Why did Seath turn on his kind? Miyazaki will never tell.

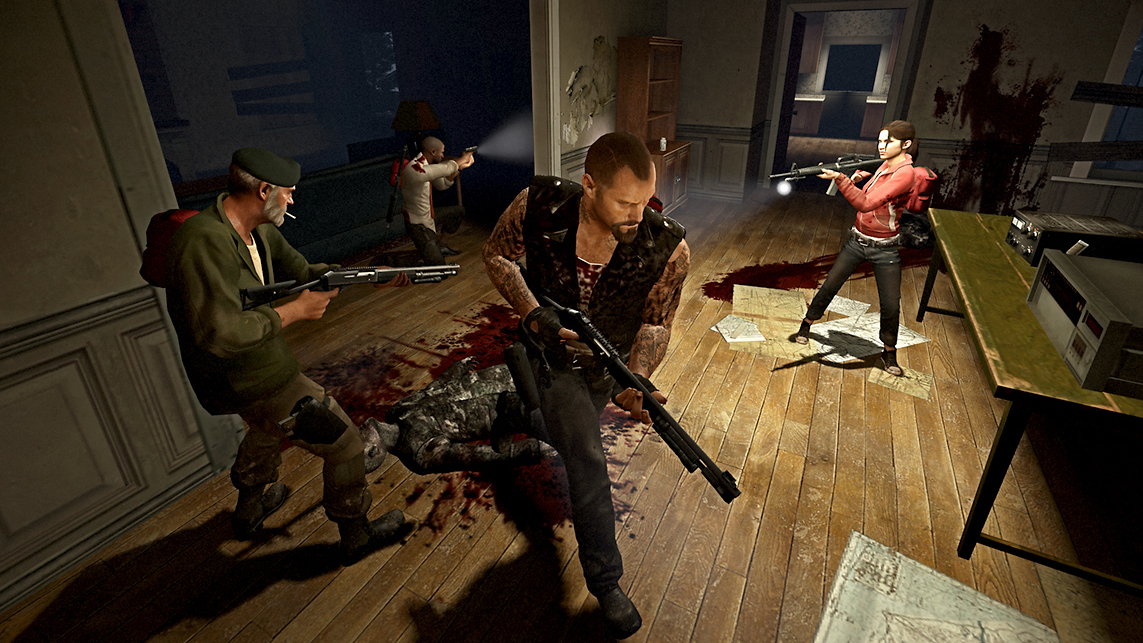

Left 4 Dead

By James Davenport

I don’t usually like zombie fiction. Zombies are an excuse for extreme character interactions, which works in comics, movies, and TV. But in Left 4 Dead and its sequel, zombies are there to be shot. The drama often happens between cooperative players and their mistakes, not the fictional shells they inhabit. Story takes a backseat to dismemberment. However, after playing the same campaigns a few times each, smaller stories begin to emerge. Graffiti messages reference others, the way a room is disheveled takes on implicit meaning, character commentary reveals events prior to and around the actual infection, and each campaign tells the story of its setting. It takes patience, but over time, Left 4 Dead’s lore leaks through regular play. DLC campaigns took it even further, connecting the characters from the first game with the second, bolstered by a beautiful series of comics. I accidentally found myself invested in a universe and characters that I originally had no intention of caring about.

MechWarrior/BattleTech

By Evan Lahti

BattleTech is one of the most novelized universes in gaming—there are almost 100 books that span three decades of lore. Summarizing that mountain of material is tough: BattleTech is basically a bunch of sports teams in space with various histories, legacies, strategies, and famous giant death robots. Many BattleTech factions are even named after threatening animals, just like your favorite football team (and then there’s Clan Fire Mandrill). Anyhoo, at one point all of these space sports teams were part of one big, happy, mostly-peaceful league, the Star League. That 200-year period of prosperity is broken by the assassination of the First Lord (aka the space president), which precipitates a power struggle and the eventual fragmentation of the Star League into a series of more divided, territorial sub-factions that make up the Inner Sphere, the area of known, colonized galactic space.

Around the same time, a general and galactic hero named Aleksandr Kerensky, tired of the bickering between the factions, peaces out of the Inner Sphere like Michael Jordan’s first retirement from basketball, taking with him a bunch of his biggest fans and military stuff to exist in isolation. Very unlike Michael Jordan, however, Kerensky’s son eventually forms the Clans, a caste-structured society driven by eugenics and insane warrior-worship. The Clans are basically a massive society of Ivan Dragos, genetically engineered MechWarriors who think they’re better than everyone else and who are always prepared to tell you.

Things really kick off when the Clans return to invade the Inner Sphere, bringing their extreme attitude of superiority to decades of war and struggle. The Clans’ power prompts the Inner Sphere to reunite under a new Star League. Overall, it’s an unnecessarily complex and convoluted battle for territory, but there’s something wonderfully American about it: the space Russians are the bad guys, corporations have a huge amount of power, and there are plenty of willing mercenaries willing to do the work of either side.

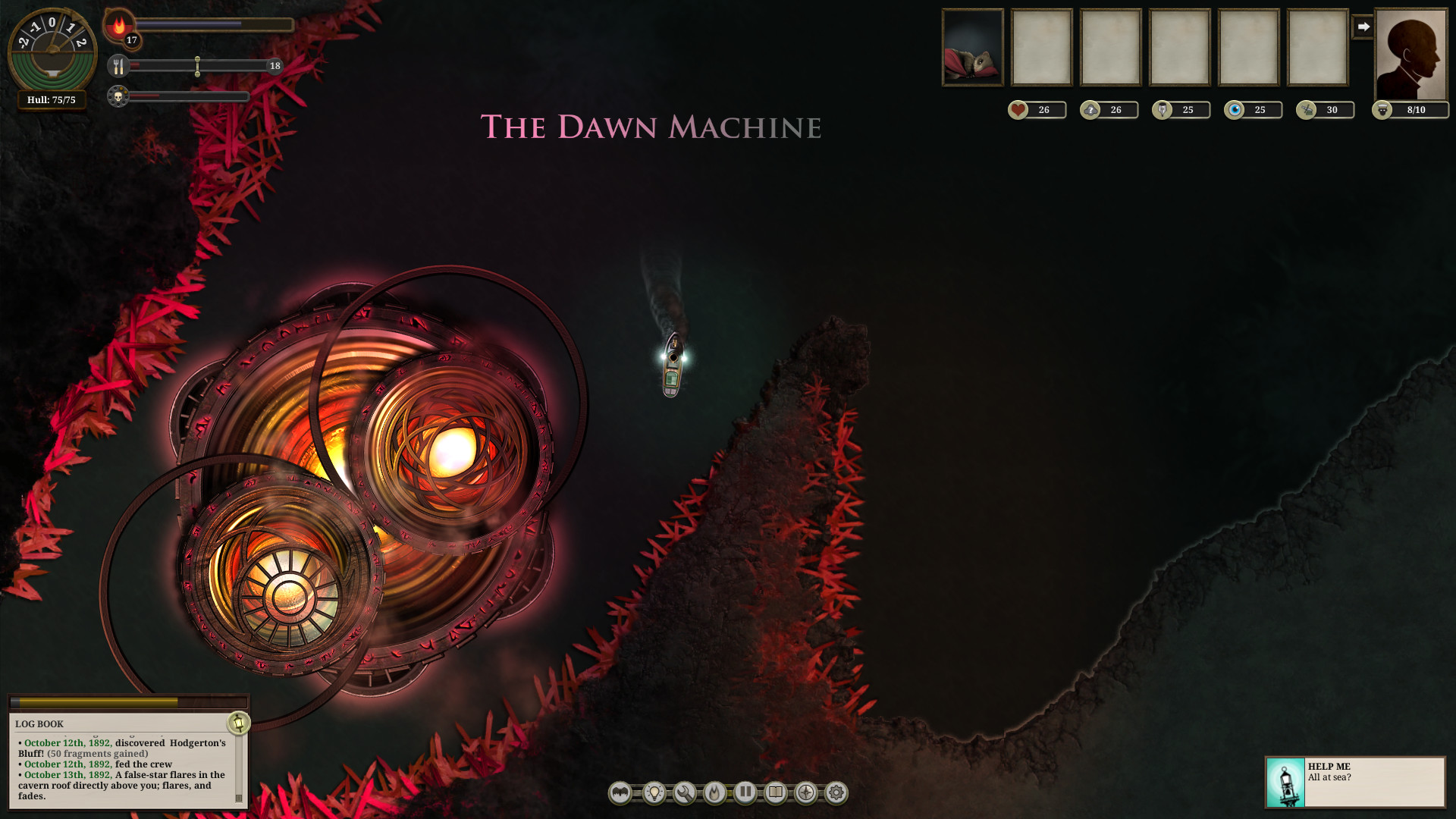

Sunless Sea

Also by Tom Senior!

There's a timeless feel to Sunless Sea's mysterious underground ocean. You play an adventurer on a quest to map the ocean (or "Unterzee", as it's called) and improve your ship. You find some strange folk on those islands. There's Venderbight to the north, where half-dead citizens of London retire when their bodies become too mangy. Three strange sisters live in an old house on Hunter's Keep. Unnamed gods and monsters come to notice you as you travel. The farther you sail from Fallen London, the stranger it gets.

Cleverly, Sunless Sea's lore isn't just a setting, but a resource to be gathered and spent. Rumours and stories are commodities you can earn and sell to unlock new quests. Every time you revisit an island, its story moves along a little, and you get a little richer. It feels like you're slowly untangling a series of disparate little tales, but quirky dark humour and elegant writing place them all in the same odd universe.

Command & Conquer

By Tyler Wilde

The Command & Conquer universe, and especially Red Alert, is about as goofy as alternate history timelines go (for instance, Einstein goes back in time and shakes young Hitler’s hand, causing Hitler to vaporize). It’s made goofier with acting from folks like Ray Wise, Tim Curry, and J.K. Simmons, with lines like "I wouldn't give a wooden nickel about your legacy," which is how the US president responds to a Soviet puppet dictator as his forces approach the American coast. God that's dumb, and I love it. (Well, not the regressive Red Alert 3 as much, but as a whole.)

The story of Red Alert isn’t so much 'lore' as it is a sequence of improbable events, but when you take it all together—Red Alert is the prequel to the Tiberium series (and whatever issues that creates can be explained with diverging timelines)—there's a ton of stupid detail in C&C. Everything from units to buildings has a reason for existing and a backstory, some of which is found in the manuals. If you want to know what guns the GDI's minigunners use—the Cobretti AR-70 and the M16 Mk. II—you can find out. Where was Tiberium discovered? The Tiber river, of course, although Kane claims he found it before the scorned scientist Ignatio Mobius and named it after Tiberius Drusus. Seems like an odd coincidence that there are two reasons for it to be named Tiberium, but that’s C&C, eh?

There are also novels. I've never opened one (I'm not that invested in C&C) but I love how seriously these massively silly games take their own fiction. I’m a bit sad that C&C may be over at this point. EA cancelled the free-to-play game (I played an early version and it wasn’t very good), but is supposedly still doing something with the series—we’ll see. Otherwise I'll have to say "construction complete" with the saddest face I can possibly make.

Vampire: The Masquerade—Bloodlines

By Andy Chalk

One of the great things about Vampire: The Masquerade—Bloodlines, the second (and, so far, final) videogame based on White Wolf’s pencil-and-paper RPG franchise, is that there is a tremendous amount of support material available to dive into, and you don't have to spend a moment with any of it to enjoy the full effect of goth-punk vampires and the endless Los Angeles night in which they live.

The game perfectly encapsulates Vampire's very specific, "Anne Rice meets Al Jourgensen" grimdark setting, and despite being incredibly dense it's also remarkably focused: It manages to hit virtually all the notes—seven unique Vampire clans, political rivalries, comedy, horror, antediluvian threats, the Sabbat, and a slew of unforgettable characters—without ever falling into self-indulgence or disarray.

The attention to detail is such that the Malkavian clan has its own unique script and in-game events, reflecting the inherent insanity of its Kindred; a stop sign, for instance, that's just another inanimate object for every other clan in the game becomes, briefly (and famously), a mortal enemy for any Malkavian who crosses its path. Technically, Bloodlines was a bloody mess when it launched, but the depth of the game world, built upon White Wolf's smouldering, sexy-vampire framework, brought it to life better than any other licensed videogame I've ever played. And more than a decade later, I still want more.

Fallout 3 and New Vegas

By Samuel Roberts

I’ve enjoyed how Bethesda’s Fallout games (and Obsidian’s) have handled world building without giving you the exact circumstances that led to the war and nuclear destruction of the United States. The story behind the world has all happened before you leave Vault 101 in Fallout 3. Through Operation Anchorage, newspaper clippings in loading screens, John Henry Eden’s broadcasts and other pieces of supplementary story, you get to learn bits and pieces about the time before, including attitudes and what civilised life was like in that universe. New Vegas, too, broadens that further with stronger links back to previous games in the series.

I love Fallout 3 and New Vegas’s use of lore because it’s all optional—and it’s not just about codexes or endless reading, which honestly, I don’t feel like I have the time to do in games anymore. It’s buried in subtle suggestions in dialogue, or environmental details. You’re never seeing all of the United States and its entire detailed history, just snapshots, and each protagonist is just one point of view on that world. Your curiosity about what exactly happened to the US and the wider world naturally grows. I find that a very powerful way to use lore.

Mass Effect

By Tim Clark

I think I fell in love with Mass Effect on the title screen, floating in orbit around earth to the accompaniment of sad ambient music that reminded me of Stars of the Lid. Then you hit a key, there’s a lovely ‘plink’ sound, and your Shep begins exploring this extinction-threatened but fundamentally optimistic sci-fi universe in which humans are posited as the bratty upstarts that most alien races just can’t even with.

There’s a clear through line to Star Trek, and plenty of other pulpy sci-fi stuff in which mankind has to form a reluctant coalition of the species to fight an overwhelming threat, but what I love most about Mass Effect’s lore is the underlying sense of melancholy throughout. All the races are dealing with Big Issues, from the roaming Quarian diaspora and their ruinous relationship with their Geth creations, to the genetically throttled (and as a result perpetually furious) Krogans.

Zooming from macro to micro, everything in Mass Effect is internally consistent, and the same sense of sadness and frustration extends down to individual characters. Thane Krios is a doomed assassin who doesn’t even like doing assassinations. Ashley Williams is a bit Fox News about the presence of aliens on the Normandy but has a good heart. Liara has major mummy issues but remains hopeful even when shit and fan seem are on an irrevocable trajectory. Like all the best gaming lore, Mass Effect’s starry backcloth isn’t something to just be consumed coldly in supporting materials though. Where you really experience it is in the game, interacting with the inhabitants and seeing the wonderful sights. It’s a universe you want to not just inhabit, but luxuriate in. Andromeda can’t come soon enough.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!