Our Verdict

A beautiful exercise in freeform solutions, Zachtronics has created one of the most satisfying puzzle games ever made.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A puzzle game about designing machines to perform alchemy

Expect to pay: $20 / £16

Developer: Zachtronics Industries

Publisher: In-house

Reviewed on: Intel i5-6600K, Nvidia GeForce 1070, 16gb RAM

Multiplayer: None

Link: Official site

If I’ve got the Latin right, Opus Magnum means “work great”. And by gosh, once you get into this puzzle game about building incredible alchemical machines, you’ll feel the buzz of working great over and over. It’s rare to play a game that provides such intense satisfaction, driven by a perfect balance of clearly defined and self-driven challenge. Flexible, intricate, demanding and deeply fulfilling, this has to be one of the very best puzzle games of the year, if not the decade.

Opus Magnum is the latest in a series of similar machine-making games to which developer Zach ’Zachtronics’ Barth has apparently devoted his creative life. Magnum is probably most similar to his first and best-known, SpaceChem, in which you build chemistry machines. He went on to make games about electronics (Shenzhen I/O), computer chips (TIS-1000), and creating factories for aliens in the first-person Infinifactory. But despite Opus Magnum’s fantastical setting, in which you play an alchemist caught between warring Germanic families, it’s probably his most accessible yet. If you bounced off SpaceChem’s cold abstractness (I did) or felt bamboozled by Shenzhen I/O’s arcane complexity (me too), you might find yourself captivated by this one.

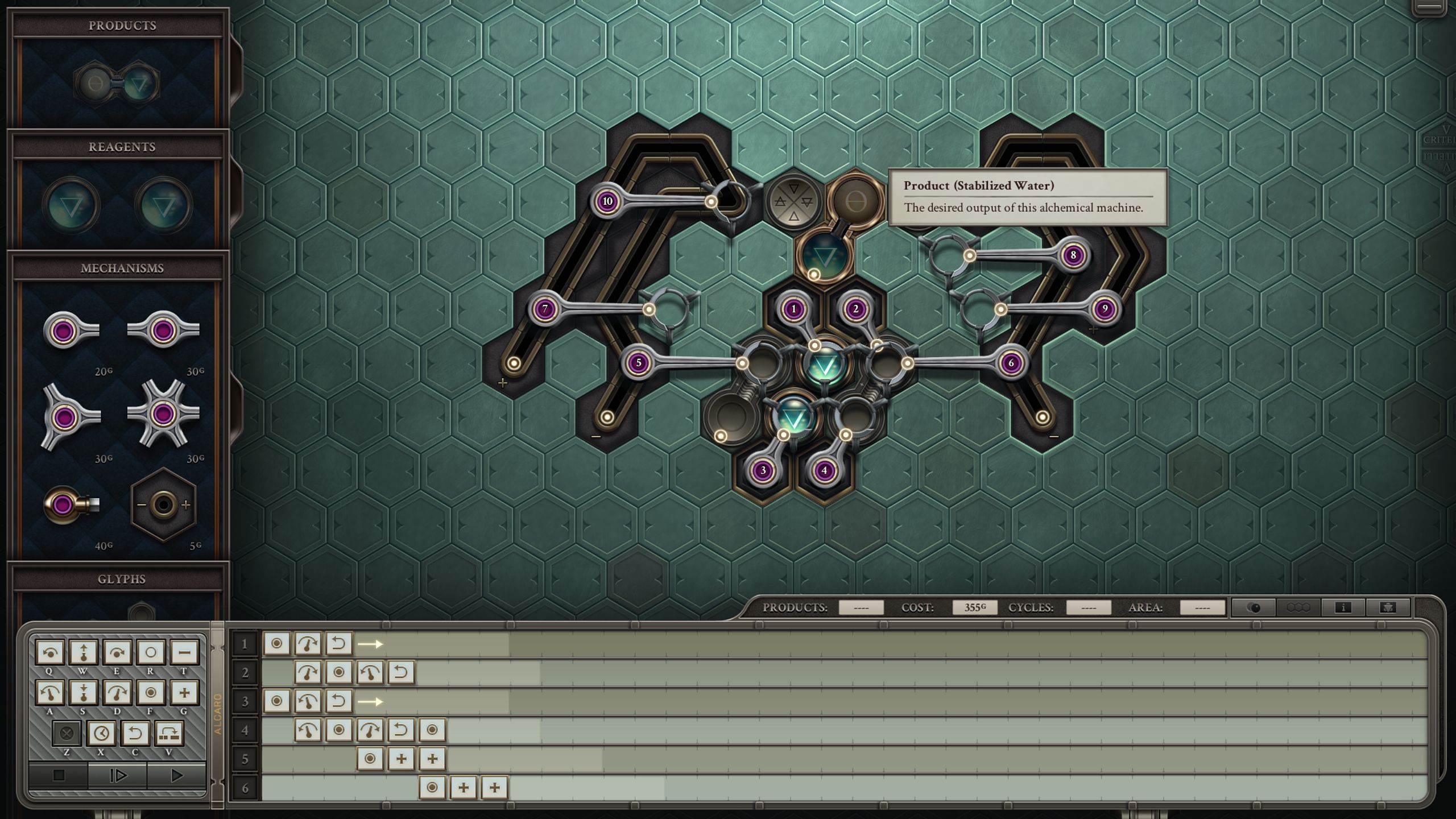

In each puzzle you’re tasked to produce a specific alchemical product. It might be booze to bolster an elderly soldier’s courage or a ladder to help stage a robbery, but whatever you’re making, it’s a set configuration of elements—air, water, fire and earth—and various types of metal. It’s your job to combine them from a predefined set of elements and components, transmuting air into salt, quicksilver into higher and higher grades of metal.

The magic to Opus Magnum is that while there are theoretical perfect machines, the space in which you construct your solution is so wide open that you feel like you’re piecing it all together entirely yourself.

You perform these actions by placing your elements and components on a table divided into hexes. You’ll use arms to pick up and move elements or rotate them in place. There are tracks which transport them across the table. There are glyphs which bond elements together when they pass over them, and some which transform elements into different ones. You command all these mechanical pieces using rules. At the bottom of the screen is a sequencer in which you place simple commands for each component on the board: pick up, put down, move clockwise or counterclockwise, extend, retract, turn, repeat, wait. So you’re essentially building machines and then programming them, building and testing your way to your solution.

The magic to Opus Magnum is that while there are theoretical perfect machines, the space in which you construct your solution is so wide open that you feel like you’re piecing it all together entirely yourself, and the restrictions are entirely common sense (elements can’t collide with each other and you can’t pull them in two directions at once), so frustrations are usually down to your own inability rather than arbitrary rules, although at a high level the technicalities by which the game times and repeats instructions can be hard to parse.

You complete a puzzle when it can churn out six products to order, and then it’s scored against three criteria: the total cost of all the components you used, the area of the table you used and how many actions your machine took. You’ll see how your Steam friends rated and a histogram showing where your ratings lie across all players; I challenge you not to feel tempted to go right back again by this to make your machine better, and to wonder, how on Earth was it possible to make it *that* quick?

The three ratings are somewhat divergent from each other—a fast machine often costs a lot, for example—so you have to decide for yourself which one you value. But before you know it, you’ll be caught up in mechanical arms races, and this, my apprentice, is when you’re playing the real Opus Magnum. It’s a game for tinkerers. You can spend hours refining, rebuilding and reimagining your machines to shave cycles off them. Put it this way: I had 12 hours on the clock when I started the second chapter of its five; 12 hours of bragging over the early puzzles with my friends, being crushed by their counter-designs, and trying to come back with something superior. Puzzle games are rarely so free-wheelingly competitive, and the pleasure in that is down to how broad your options are. Heck, you can forget the ratings and build the most insanely convoluted machines instead. If it works, it works.

The fact that Opus Magnum is exquisitely presented, with each arm and component cast in burnished steel and moving with faultless precision just seals its appeal. I can watch my machines’ dances of arms and pistons, patterns of elements slotting perfectly into place, forever. And, naturally, you can generate gifs of them at a click of a button so everyone else can appreciate your genius. That simple feeling, of personal pride in a creation plugs into the very best qualities of not only the puzzle genre but all of creative play. Opus Magnum works great because it gets you to work great.

A beautiful exercise in freeform solutions, Zachtronics has created one of the most satisfying puzzle games ever made.